Open New Paths to Learning in the Literature Classroom with Choice Boards

By Kathleen M. Scollins, Associate Professor of Russian, University of Vermont

Last spring’s so-called “pivot” to online learning felt like something closer to an abrupt lurch to many language instructors, faced with the task of translating the high-energy interactions of the in-person language class to an unfamiliar online setting. In response, one subfield of the pedagogical landscape burst into bloom as professional organizations, journals, and social media sites took up the task of offering workshops, panels, webinars, and new forums devoted to the specialized tasks of language teaching (for examples, see FLTMAG Resources for COVID-19). As a result, even the luddites among us entered the 2020-21 academic year armed with new strategies, supports, digital tools, and confidence. Many language instructors, however, also teach literature or culture courses in translation—and while some of the tools in our new digital arsenal might transfer to other pedagogical settings, many are uniquely suited to the language class. Overall, the field has seen fewer resources devoted to the other major pivot many of us were expected to master over the past year.

One of the more successful digital strategies I implemented in my own Literature in Translation course this past year was something that I called a “Choice Board” (aka Learning Menu): a grid presenting a visually organized set of activities, from which students select one or more to complete. They can be used in a variety of learning contexts, both in and out of class time, from structuring small-group discussion to assigning projects for students to work on independently. Since this was my first time teaching a mixed-modality discussion class, with some students in the physical classroom and others attending from home via Microsoft Teams, I needed to find tech tools that would be as easily viewed and accessed by students in the classroom as by those online. Before the semester began, I envisioned Choice Boards as a simple way to present the various extra-literary activities students might elect to complete on their own for each of the course’s six modules. As I discovered, however, they are much more than just graphic organizers: the act of making choices gave students a greater sense of agency, accountability, and connection to the material, pushing them to engage in deeper, more varied ways with the texts. Though I will be returning to a more traditional in-person teaching modality in the fall, I plan to continue making Choice Boards a major component of the course structure.

What are Choice Boards (aka Learning Menus)?

A Choice Board allows learners to view and consider a set of options before deciding which of them to complete; depending on the particular learning goals of a given lesson, instructors might direct individual or groups of students to select:

- a particular number of activities of their choice;

- all tasks in a single row of their choice, tic-tac-toe style;

- all tasks on the board, but in an order of their choosing.

The Choice Board concept has been around for decades, ever since K-12 educators began to shift away from traditional models—by which educational content was delivered via a single instructional method to an entire classroom—in order to reach a broader range of learners by differentiating instruction. As Alfie Kohn noted in his classic article on the benefits of introducing student choice, “It is not ‘utopian’ or ‘naïve’ to think that learners can make responsible decisions about their own learning; those words best describe the belief that any group of people will do something effectively and enthusiastically when they are unable to make choices about what they are doing” (Kohn, 1993). Offering a limited array of choices, he argued, would grant students greater agency over their own learning, which in turn would increase both motivation and outcomes. By bringing choice into lesson plans, instructors allow students to engage with the material in the way(s) that hold the most meaning and value for them, encouraging them to dive more deeply into course content.

In practice, early versions of the Choice Board were little more than photocopied lists of activities, detailing various ways students might master (or display mastery over) a particular concept, keeping multiple learning styles in mind. Digital-age Choice Boards preserve the basic concept of prompting students to participate more actively in their education by forging their own learning path, but they have grown more sophisticated in form and diverse in offerings. Creating Choice Boards with hyperdocs like Google Docs, for instance, enables instructors to insert hyperlinks within each choice; the resulting document includes links to any digital tools necessary for completing the various activities (instructions, websites, playlists, discussion boards, etc.), streamlining the process for both instructor (who only needs to share a single document) and students. Last year’s shift to online- and hybrid learning brought new prominence to such hyperdoc-enhanced Choice Boards, which can organize, present, and facilitate a variety of learning options, whether students are in a classroom, on Zoom, at home, or a combination.

Uses and Examples

Choice Boards offer a broad range of opportunities for differentiated instruction and student autonomy, both in and out of the classroom.

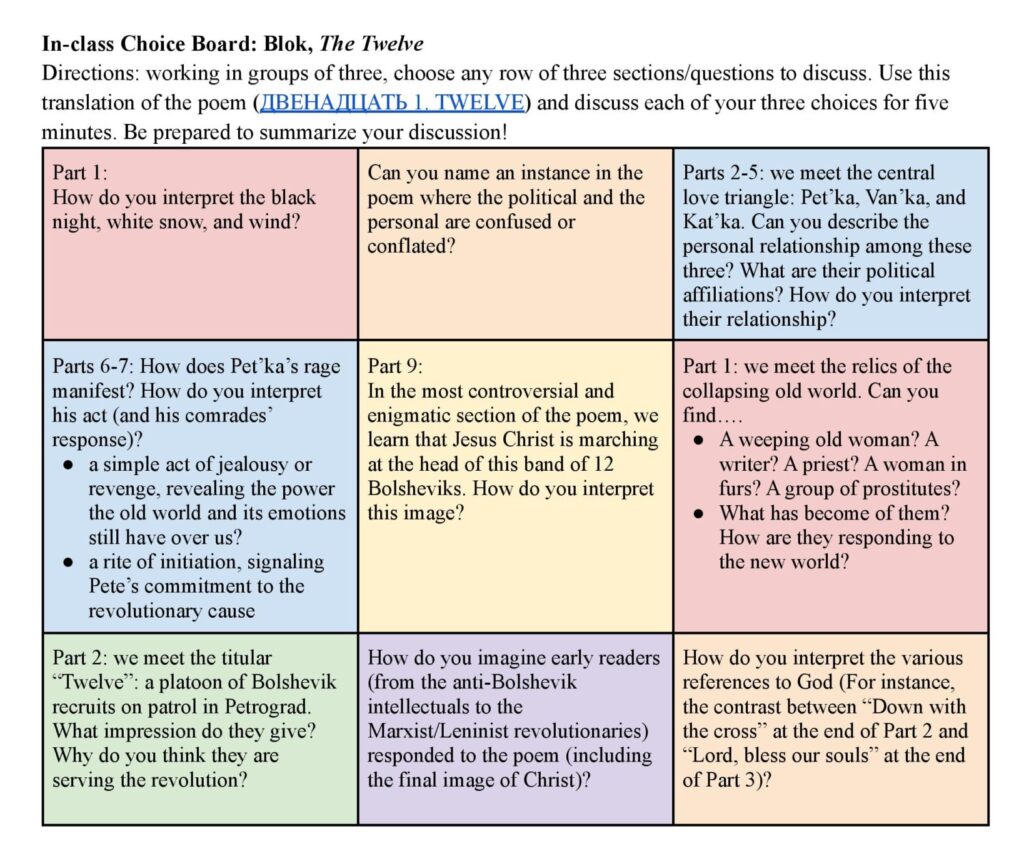

In class, they can be used to promote more active participation during pair or small group work. This very simple board, presenting discussion questions for Aleksandr Blok’s narrative poem The Twelve, invites small groups to select a set of passages to analyze. The questions are the same ones I’ve used to facilitate discussion of this complex poem in the past; embedding them in a Choice Board, however, resulted in a deeper and more lively dialogue, as students took more ownership over the sections they’d chosen for analysis and made unexpected connections in passages across the poem.

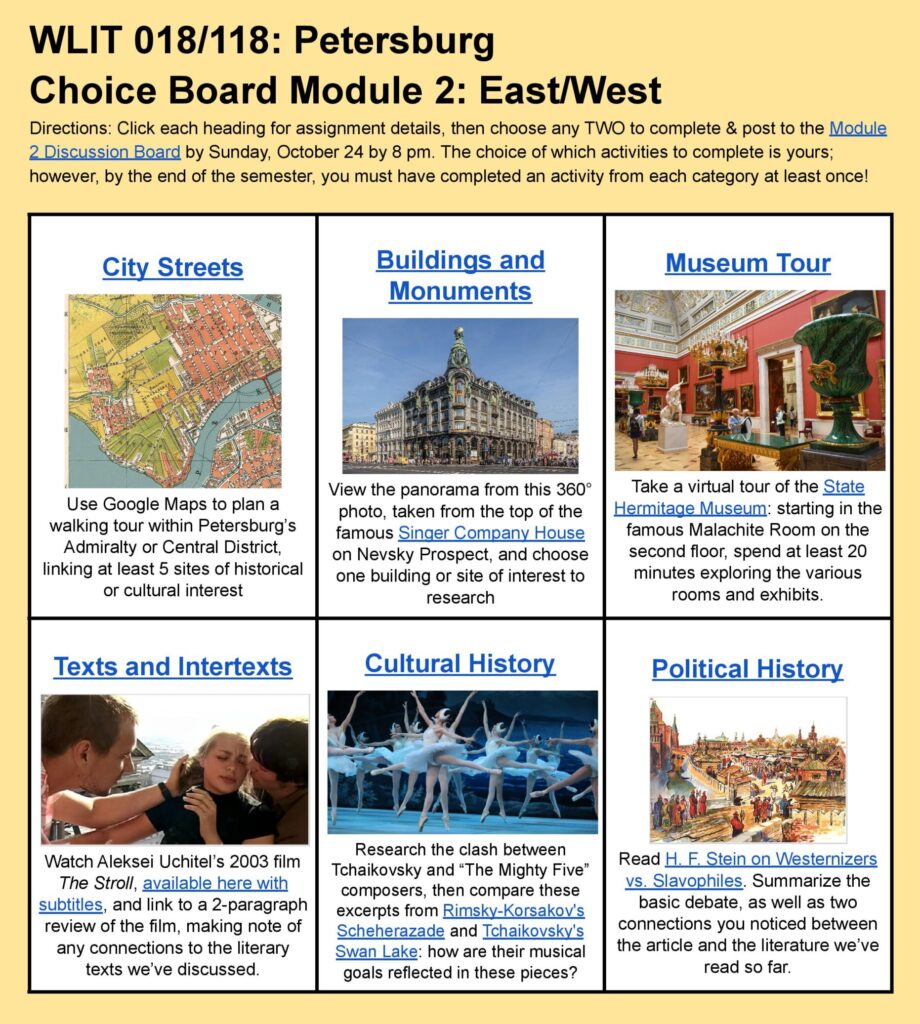

My favorite way to use Choice Boards in my literature course this past year was to increase the amount and variety of material we were able to cover by offloading some of the work to students. The course I was teaching, “The Soviet Experience,” fulfills our university’s Gen Ed requirement in literature and attracts mainly non-Russian majors. Since I could not assume any background knowledge in either Russian language or history, I turned to Choice Boards as a way of including contextualizing material without taking up too much class time. For each of the six modules, students were directed to complete any two choices; over the course of the semester, they needed to try each category at least once. Since this particular course focused on the lived experience of the Soviet Union, I organized my board according to sensory and material aspects of Soviet life, and the categories related to the senses: See, Hear, Taste, Touch, Feel, Think. Student responses were posted to a digital bulletin board (I used Padlet), which everyone read and we briefly discussed in class.

![The Communal: Module 2 Choice Board Directions: choose any TWO of the following to complete on your own & post to Module 2 Padlet by Sunday, March 14 by 8 pm. The choice of which TWO activities to complete is yours. However, by the end of the semester, you must have completed all of the following: At least one activity from each category At least two film assignments (“See”) At least two critical article assignments (“Think”) SEE: Watch “Bed and Sofa” [Третья Мещанская] by Abram Room: Bed and Sofa (1927). On Padlet, post a link to a 1-page film review, along with a screenshot of your favorite still image from the film. HEAR: Listen to the music of the decadent 20s (NEP-era playlist) and post a brief response to Padlet: How are these songs designed to make you feel, and do they accomplish that? Which is your favorite, and why? Find the song & post a link (with a screenshot)! Are there equivalent eras in American music? TASTE: Read chapter 2 of Mastering the Art of Soviet Cooking (Von Bremzen_1920s: Lenin's Cake.pdf). Find an image (or making-of video) of one of the dishes she mentions. Post a link to a brief “recipe review” on Padlet: why was this dish so popular, and what did it represent? (Students living at home should try to make and review a recipe from the era!) TOUCH: Browse scans from Litvina’s The Apartment for the year 1927 (Apartment - 1927.pdf) and read this article on 1920s Soviet fashion: Gorsuch_Moscow Chic. Draw upon both sources to post a detailed glossary of 10 new items (along with an image of your favorite), and briefly discuss how the material culture of the 1920s reflects the ambivalences of the NEP era. FEEL: Read one of the following articles on youth, sex, and the emphasis on “Physical Culture” [физкультура] in the 1920s: Fitzpatrick_Sex and Revolution; Grant_Creation of Ideal Young Citizens. On Padlet, briefly summarize two new facts you learned about the physical experience of life in the Soviet NEP era; are there equivalent eras in US history? THINK: Read about the Communal apartment, which became a fixture of Soviet life in the 1920s: Gerasimova_Public Privacy in the Communal Apartment. Summarize two interesting facts you learned about communal life at this time, and two connections you noticed between the article and the Bulgakov and Zoshchenko stories we have read. How does this cultural history help to illuminate these works of literature?](https://fltmag.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Mod-2-Choice-Board-SovExp-791x1024.jpg)

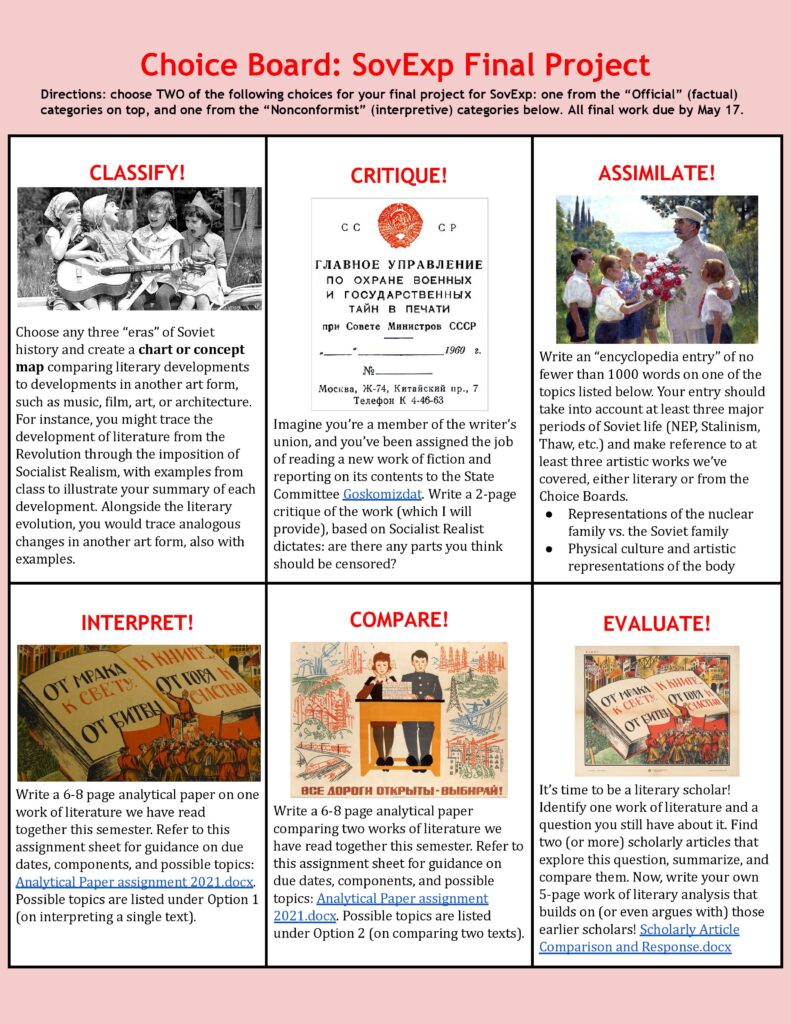

Choice Boards can also be an effective tool for organizing course review: just arrange authors, works, and literary movements into separate columns, and assign students to choose one from each column; after spending a designated period reviewing and taking notes, they report back to one another in small groups. When assigning papers, Choice Boards can be a great way to present passages for Close Readings or options for analytical papers — I used the one below to organize final project options at the end of my Soviet Experience class.

Creating a Choice Board

Instructors can use their preferred digital tool to create a Choice Board; I have chosen to use Google Docs or Slides, which are familiar, free, and easy to integrate into my Google-based class structure; other options include Wakelet, Padlet, and OneNote. Here are steps you can use to create your own:

- First, brainstorm: How many options do you want to offer, and what are the categories? How will students submit or post their work? Will they post publicly, or just for you? Will they be expected to view or comment on others’ work (on a linked discussion board), or will they submit to a private folder? This is all up to you, depending on course learning goals;

- Now, create your digital Choice Board by going to Google Drive, creating a new project (either doc or slide), and giving it a title;

- Once you’ve decided how many choices you’d like to offer, you can either insert a table with the correct number of boxes or—if you have an uneven number of options or you’d prefer boxes of various sizes—simply create the correct number of text boxes. If you’d prefer to view examples or work from a template, there are many models that are easily accessible online—most are intended for the K-12 classroom, but are easy to edit and adapt;

- In each box, create an assignment: insert images or hyperlinks as needed to scaffold the activity (with links to readings, videos, etc.) or provide the digital tools necessary to perform it (links to Padlet, Flipgrid, Powtoon, Vocaroo, or other apps students will use to complete or post their work);

- Add directions: how many activities to complete, when/where to post responses, how to access other students’ work, etc.;

- Share your completed Choice Board by clicking the blue share button in the upper right corner and copying/sending the URL (or embedding in your class slides or schedule of assignments). Be sure to set permissions to “view,” which will enable students to follow any necessary links (while preventing them from inadvertently editing your work).

Conclusion

Now that we’ve survived over a full year of (involuntary, for most of us) online or hybrid teaching, we are faced with the opportunity to assess which of the tools in our expanded digital arsenal to keep, and which to happily discard (Gacs, Goertler, and Spasova, 2020). I am grateful for the wide variety of resources that emerged along with our “pivot” to online learning, which armed many of us for the special challenges of teaching languages in an online or hybrid setting. Like many language instructors, however, I also teach discussion-based courses on literature or culture in translation, and I found fewer resources available to help me adapt those courses to the exigencies of pandemic-age teaching.

The digital Choice Board was one very flexible, low-tech instrument I found indispensable in my courses in translation, enabling me to differentiate instruction in large, mixed-level classrooms. Incorporating different ways to engage with the material enabled me to reach those students who—because their academic training is in the creative arts, social sciences, or hard sciences—don’t have the writing or analytical background to feel comfortable in a traditional literature class. Delegating contextual cultural or historical information to students allowed me to devote more class time to developing tools of literary analysis, and allowed the students to take the lead in areas they felt more control over (for instance, my science students enjoyed reading about Soviet “physical culture,” and my arts students always had music and film options). I found that when students were equipped to choose their own path to the material, their sense of empowerment led them to dive in more deeply, resulting in unexpected connections, increased participation, and richer discussion overall.

References

Gacs, A., Goertler, S., & Spasova, S. (2020). Planned online language education versus crisis-prompted online language teaching: Lessons for the future. Foreign Language Annals, 53(2), 380–392. https://doi.org/10.1111/flan.12460

Kohn, Alfie. (1993). Choices for children. Phi Delta Kappan 75(1), 8-20. https://www.alfiekohn.org/article/choices-children/

The Editors of The FLTMAG. (2021). FLTMAG resources for COVID-19. The FLTMAG. FLTMAG Resources for COVID-19

![The Communal: Module 2 Choice Board Directions: choose any TWO of the following to complete on your own & post to Module 2 Padlet by Sunday, March 14 by 8 pm. The choice of which TWO activities to complete is yours. However, by the end of the semester, you must have completed all of the following: At least one activity from each category At least two film assignments (“See”) At least two critical article assignments (“Think”) SEE: Watch “Bed and Sofa” [Третья Мещанская] by Abram Room: Bed and Sofa (1927). On Padlet, post a link to a 1-page film review, along with a screenshot of your favorite still image from the film. HEAR: Listen to the music of the decadent 20s (NEP-era playlist) and post a brief response to Padlet: How are these songs designed to make you feel, and do they accomplish that? Which is your favorite, and why? Find the song & post a link (with a screenshot)! Are there equivalent eras in American music? TASTE: Read chapter 2 of Mastering the Art of Soviet Cooking (Von Bremzen_1920s: Lenin's Cake.pdf). Find an image (or making-of video) of one of the dishes she mentions. Post a link to a brief “recipe review” on Padlet: why was this dish so popular, and what did it represent? (Students living at home should try to make and review a recipe from the era!) TOUCH: Browse scans from Litvina’s The Apartment for the year 1927 (Apartment - 1927.pdf) and read this article on 1920s Soviet fashion: Gorsuch_Moscow Chic. Draw upon both sources to post a detailed glossary of 10 new items (along with an image of your favorite), and briefly discuss how the material culture of the 1920s reflects the ambivalences of the NEP era. FEEL: Read one of the following articles on youth, sex, and the emphasis on “Physical Culture” [физкультура] in the 1920s: Fitzpatrick_Sex and Revolution; Grant_Creation of Ideal Young Citizens. On Padlet, briefly summarize two new facts you learned about the physical experience of life in the Soviet NEP era; are there equivalent eras in US history? THINK: Read about the Communal apartment, which became a fixture of Soviet life in the 1920s: Gerasimova_Public Privacy in the Communal Apartment. Summarize two interesting facts you learned about communal life at this time, and two connections you noticed between the article and the Bulgakov and Zoshchenko stories we have read. How does this cultural history help to illuminate these works of literature?](https://fltmag.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Mod-2-Choice-Board-SovExp-scaled-e1628361629777-1400x600.jpg)