To Sync or Not to Sync, That is the Question: Choosing Between Synchronous and Asynchronous Modes in Remote and Online Language Teaching

By Marlene Johnshoy, University of Minnesota, and Shannon Donnally Spasova, Michigan State University

DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.69732/QRHG6110

One of the most important decisions you will make when planning an online language course is whether the course will be synchronous, asynchronous, or a mixture of the two. Since the spring 2020 move by institutions to emergency remote teaching, there has been a lot of debate on social media about the advisability and the ethics of requiring students who did not sign up for online learning to participate in synchronous sessions. On the other hand, many language teachers are concerned about how to incorporate live interactions for developing language proficiency. Now that the unexpected phase of the crisis has passed, and most of us are working on planning for summer and even possibly fall courses online, we should begin to engage in the rigorous process of planning ahead for how we will handle our online courses as those who have been teaching language online regularly do. In an ideal world, an instructor of an online course would have six months to a year to think carefully through all of the choices that would contribute to making the course run well online. In the situation that we find ourselves in now with COVID-19 shutting down many campuses across the world, however, many of us will need to plan to teach online with a lot less time to prepare. This article seeks to help you think through one vitally important element of your online course – whether it will be conducted primarily synchronously or asynchronously.

Definitions and examples

Synchronous online learning is class work that happens with all of the students and the instructor engaging with each other in the same time and online space, usually achieved through some kind of video conferencing. Asynchronous online learning is made up of activities that are created in advance and then students access and complete them according to their own schedule, usually with scheduled due dates. If a course runs without scheduled due dates, it would probably be considered a self-paced asynchronous course, sometimes with just a final end-of-course deadline. Consider a couple of examples of programs that make different choices about the way they will deliver content to students.

One program teaches language to many military personnel – who can’t meet synchronously or install anything on their computers for security reasons, and need to be entirely flexible with the time they put into the class. They use an entirely asynchronous delivery. Another program has an interactive television network that connects some of their campuses around the state, and they use an entirely synchronous delivery format where the students always need to attend the class every day or two at the same time with their classmates, but the teacher is remote, at another location. There is no flexibility in the schedule, everyone meets together at the same time. Many others use a combination of the two, mostly asynchronous activities that the students can do when they have time (working, families, other classes, etc. can make schedules difficult), and the occasional synchronous session for questions or group work.

Which delivery format will you choose, and why?

During this COVID-19 pandemic, when you are reacting to circumstances that are changing extremely quickly, you may not have the time to engage in a formal needs analysis. However, you should spend a bit of time thinking about your student population and their needs. If you are able, you may want to send a survey to your student population or a subset of your students to find out more information about them and the conditions in which they will be taking your class. You will also want to take institutional factors into account when making decisions about your courses.

Some of the questions that need to be considered are:

- Has your institution or district mandated one type of delivery or another?

- Do you have restrictions about whether or how you can ask your learners to participate in synchronous sessions? Are any platforms or applications restricted? These may be especially relevant if you teach minors.

- Do your courses need to be consistent across programs or sections, or are instructors allowed to make personal choices about how their courses will be conducted?

- Do your students have access to sufficiently strong internet connections that they can use to regularly and productively engage in video conferencing or with online materials and activities?

- Do your students have the equipment necessary for successful video conferencing (like a webcam and microphone, or a device that is able to download software if necessary)?

- Do your students have support options for not only technology, but also access to library materials, mental health issues, and other supports that they would normally be able to take advantage of on campus?

- Do your students have restrictions to their schedules that would make it difficult for them to participate in scheduled synchronous sessions?

- Do your students have any challenges that would preclude ease of typing to keep up in a text chat, for example, or difficulty understanding spoken language through networks that are not always crystal clear?

- Are your students scattered across many time zones, which would make it difficult for them to participate in scheduled synchronous sessions?

- Are your students able to type in the target language? If they cannot, there will be fewer types of activities that you will be able to use in your course. This is especially relevant for those teaching languages with non-Latin alphabets.

Depending on some of these factors, you may determine that asynchronous delivery should be the bulk or some of your instruction. The asynchronous format has some clear advantages, even beyond the flexibility in time that it offers. Asynchronous materials can be easier to complete for those without robust internet connections, and can assist instructors with differentiation. Students can take as much time as they need with materials instead of needing to conform to the time restraints of a synchronous class, and some asynchronous materials can have targeted automatic feedback that gives the potential for students to become more independent learners. These rich activities do take a lot of time to develop, however, and if they are not available within our language teaching communities, many of us do not have the time or expertise to devote to this type of curriculum development. Note that for some languages there are commercially-available resources that may be able to be used. We are beginning to see resources and repositories of online materials available to teachers of less commonly taught languages. For example, the LLC Commons is a project that provides free online materials for Russian language courses, and other languages may have similar shared resources.

We also believe, however, that synchronous learning has distinct advantages that make it worth considering, whether it be an entirely synchronous-based class or whether it can be integrated into an asynchronous language course weekly. Synchronous learning can be seen as more immediately interactive, possessing more personal “presence”, and it is more like what students who have never done online learning before might expect from a language class. Furthermore, it is difficult to do language learning activities in the interpersonal mode asynchronously. Synchronous sessions offer the ability to put students in “breakout rooms” to have partner and small group conversations in real time.

Online courses do suffer from higher attrition than face-to-face courses, and part of this may be that it can be easier for some students to fall through the cracks when they do not meet synchronously with their instructor regularly. Students must have the self-discipline to complete work without the outside accountability of an instructor in real time. Either way, teachers need ways to track student participation and engagement and stay in communication with students. Teachers also need to work on creating community in their courses, which tends to come naturally in a face-to-face environment where students see and chat with each other before and after class, but this community needs to be carefully cultivated in online courses, especially asynchronous courses, where students can feel isolated and disconnected.

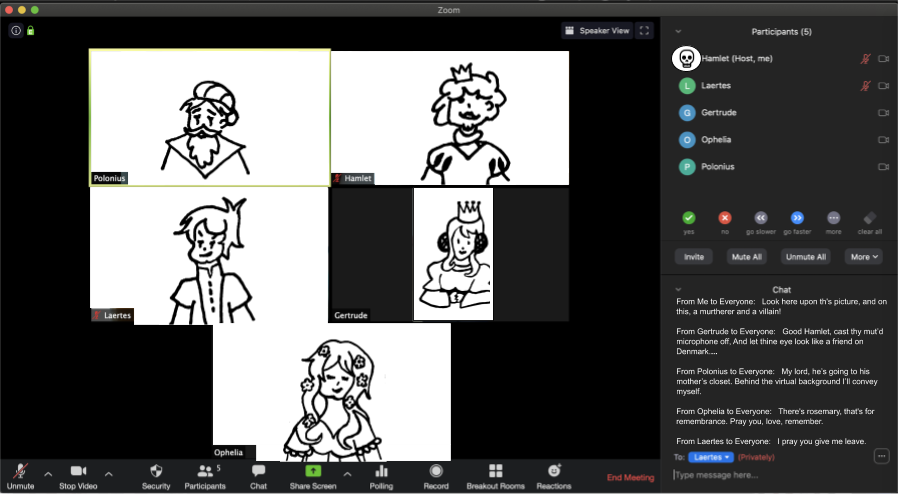

There is a danger of too much time in video conferencing, however, especially if students are required to do video conferencing for all of their courses. With so many working and studying from home, many news outlets are discussing “Zoom fatigue”, and its seemingly real effects on productivity and mental health. Teachers are also discussing the same fatigue, as it is much harder to interpret student reactions online. In either format, teachers need to encourage students to be proactive about asking for help when learning online.

Each situation will require a different solution, but if possible, we would encourage instructors to adopt a mixture of synchronous and asynchronous elements for their online language classes. Some of both formats could offer the benefits of both while easing some of the difficulties. A once or twice-a-week synchronous session, perhaps in small groups, would help keep the personal touch and ease of answering questions that students might have. At the same time, the asynchronous portion of the course would let students work on activities at their own pace, meet with a speaking partner at a time of convenience, and ease the burden of videoconferencing and scheduling. This combination is similar in concept to “flipped” lessons, where students do learning and practice outside of class so that during class, the focus can be on interaction and conversation.

With careful planning and decision-making, online language courses can be very successful and rewarding. As you expand your experience with teaching using technology, your new skills will benefit your students in the current situation, as well as in the future.

For further reference on synchronous versus asynchronous delivery, see the following resources:

Please leave a comment below about the choices that you are making about how to structure your online language courses.

I am also teaching 100% synchronuosly on-line this semester. The Zoom fatigue is real for both instructors and students. I have opted to cancel extracurricular activities such as conversation tables via Zoom due to low attendance. I replaced the conversation table by a non-structured tandem-like activity, that is, I partnered students with native speakers of the target language to increase engagement outside the classroom.

I’ll be teaching Spanish 1 100% online in the fall. Since it’s my first time teaching online, I chose a synchronous class. I thought that if the students are together at the same time it’s easier to create a sense of community.