How to Establish a Strong Community in an Online Course

By Magara Maeda, University of Wisconsin River Falls and Lauren Rosen, University of Wisconsin Collaborative Language Program

DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.69732/FQES8608

One of the most common questions we hear from instructors who are first moving to an online teaching environment is, “How do I build community in an online class?” For some reason we have equated the idea of being in the same physical space and meeting at the same time as developing a community. Would you also say that a 200+ full lecture hall automatically provides a sense of community simply because all of the students are in the same physical space at the same time? Of course not. At CU Boulder, where the average “large” lecture size is 97 students, students were surveyed regarding their level of engagement in these large lectures. Not surprisingly this survey resulted in tips for instructors to intentionally create an environment of engagement, it wasn’t automatically present simply due to students’ physical presence (McAndrew, Dykeman, Fell, & Nussbaum, 2018). Similarly there were some tips created for students as well. It takes intention to build a community whether in a face to face or an online environment. It also takes a combination of interactions, student to student, student to instructor, and student to content. This article will address the development of community in online language courses using the Community of Inquiry framework. Within the scope of this framework you will also see the three primary types of interaction that occur in a course, student-student, student-instructor and student-content. While there will be a few technologies mentioned, the technology does not create the interaction nor does it build community. It is all about the task that you, the instructor, design to define the interaction and presences (social, teaching, and cognitive) that are supporting the building of community. Social presence is defined as students engaging with a learning community where trust has been sufficiently established for students to feel comfortable with risk-taking, and where relationships are built through personal connection with each other and the content. You can already see in its definition the influence of the aforementioned three interaction types. Teaching presence reflects the design and development of the course as well as the interaction of the instructor supporting students throughout course delivery, both synchronously and asynchronously. For a course to be effectively taught there needs to be a series of activities that are active and engaging to the students. This engagement is where students construct meaning by connecting to the content and in the case of languages begin creating, synthesizing and analyzing in the target language. It is that level of higher order thinking that defines the cognitive presence and the connection to student and instructor interactions.

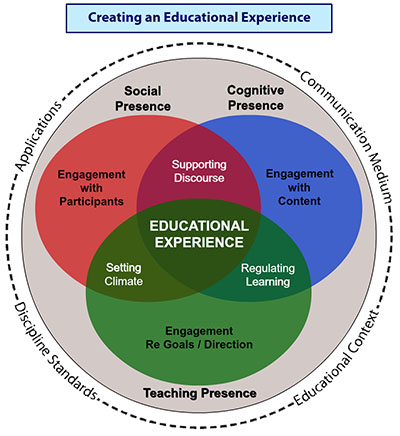

The Community of Inquiry (CoI) theoretical framework (Garrison, Anderson & Archer, 2001) is perhaps the best-known and most researched approach to designing learning experiences for the online environment. It represents a process of creating a deep and meaningful (collaborative-constructivist) learning experience through the development of three interdependent elements: social, cognitive and teaching presence (depicted in Picture 1 below). In fact, these presences have been shown to be the most significant variables in the success and effectiveness of learning in an online environment.

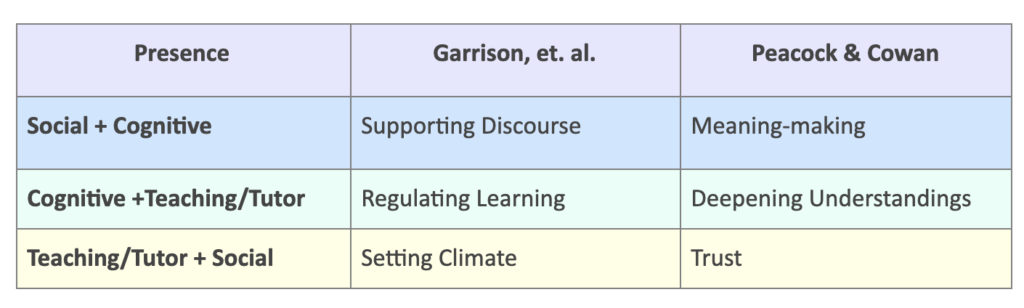

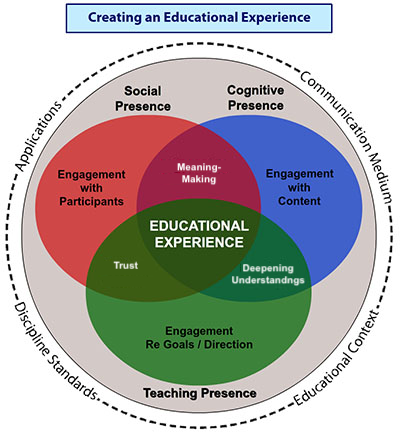

Peacock and Cowan (2016) took this framework one step further while considering the interaction between the presences and how they influence each other. Peacock and Cowan offer insight into the linked influences of the Presences within the Communities of Inquiry in their article, From Presences to Linked Influences Within Communities of Inquiry.

In the areas of overlap between the presences we can see the differences between how Garrison, et. al. identify the intersection versus that of Peacock and Cowan’s interpretation of their interconnected influences. Notice the change in the original graphic where the intersection between presences occurs. Peacock and Cowan aim to “address constructively some of the challenges of online learning, including learner isolation, limited learner experience of collaborative group work and underdeveloped higher-level abilities.” We propose, and the CU Boulder survey supports, that these same experiences can challenge traditional courses as well without the intentional efforts on the part of both instructors and students to design synchronous learning to support the overlapping presences of the Community of Inquiry framework.

Social, teaching and cognitive presences all play a significant role in community building in online learning environments, both synchronous and asynchronous modes. While the information below describes each presence in greater depth, it is the interaction of two or more presences that will most influence the success of community building. The following is a summary of each presence along with suggested tips and strategies. These tips have been adapted from Designing for Learning: Library of eCoaching Tips and have been put into practice in numerous blended and online language courses in the University of Wisconsin System Collaborative Language Program.

Social Presence

Social presence is “the ability of participants to identify with the community (e.g., course of study), communicate purposefully in a trusting environment, and develop interpersonal relationships by way of projecting their individual personalities” (Garrison, 2009). Learners want to get to know their instructors as people in addition to their roles as mentors and content experts. Online students need the social presence of the instructor and other students to feel as if they are part of the online learning community, reducing feelings of isolation while building trust and connection.

Tips for developing social presence:

- Create a discussion forum, where you introduce yourself, provide some personal information including a picture, and ask students to provide similar introductions.

- Always address students by name and keep track of what you learn about individual students to help reinforce the bond.

- Include personal information that you feel comfortable sharing (i.e. hobbies, work experience, family, pets, etc.) in your instructor profile in the learning management system (LMS) and encourage students to do the same. (See sample below.)

- Keep a notebook (digital or paper with 1 page per student to help track and maintain what you learn throughout the course. You can use this information to connect content to the students’ interests.

- Create a “coffee break” discussion board where participants can regularly post personal or anecdotal information.

- Connect using humor. Remember that it’s hard to read tone in text so use graphics, videos, emojis, and other methods to ensure students recognize it as humor.

- Whenever possible personalize your course introductions using video or audio.

- Show empathy. Be approachable and sense when your students need help and support by recognizing changes in behavior.

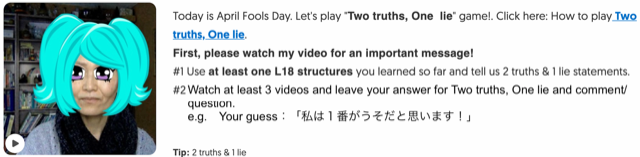

There are technologies that also help create social opportunities for students. Flipgrid, a free video-based discussion platform, is a great tool to promote active asynchronous communication and to build community among students. Building community while connecting with content is meaning making. Just like a discussion forum, a teacher using Flipgrid posts a topic, a video prompt, a question, or any combination thereof. The students respond in a video. The trick is creating the kind of prompt that would generate a conversation where students reply to one another. This is often where students shine through with humor and interests that you can draw upon for subsequent activities.

Following best practices when using a tool such as Flipgrid for speaking assignments, the instructor creates a model video (see Picture 5 below). This is where the task created is important if it is to meet the objective of student to student interaction. Students need a reason to listen and to reply to videos posted by their peers. Two key elements of an interpersonal task in this situation would be a motivating/interesting topic and a question to be answered. One example Once the conversation has begun between the students, it’s important for the instructor to show some involvement with the threads. This involvement may be as simple as liking a video that your students post, response to a student video, or it might be holding up one of your students’ examples as a model for others. You will learn more about the role of “teaching presence” in the next section. This is an example of the interaction between social and teaching presence that influences the building of a stronger community.

Remember that a strong social presence establishes a climate of trust and an environment of comfort and safe risk-taking. Humor can come in the form of content, emojis, and other digital decorations that students find engaging. This safe space prepares the learners for the interactions in teaching and cognitive presence.

Teaching Presence

Research from the Community of Inquiry Model found that the instructor’s presence and engagement with online learners is the most significant variable in the effectiveness of teaching and the satisfaction of the learners.. Teaching presence is the “design, facilitation, and direction of cognitive and social processes for the purpose of realizing personally meaningful and educationally worthwhile learning outcomes” (Anderson, Rourke, Garrison, & Archer, 2001). Simply explained, teaching presence includes designing and developing the course in addition to guiding and supporting the learners during the course delivery.

Tips for building teaching presence:

- Before the course begins, email each student outlining course and time expectations so that students are clear as to what will be needed to succeed.

- Provide learning guides for each unit that set clear expectations for students.

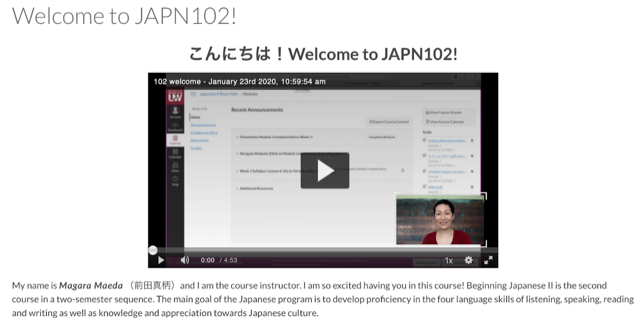

- Start the course with a welcome video introducing yourself to your students. In the following weeks consider using this video medium to introduce the expectations for each week.(See example below.)

- Be visibly present in the course, following through on promises about what students should expect from you, e.g. how soon you will respond to an email from students.

- Use LMS announcements, reminders and direct emails to coach learners to keep pace with their learning and ensure students are aware of responsibilities, due dates, and other activities.

- Provide a space in your course for general questions/discussion. Answer questions regarding activities and assignments in a timely fashion.

- Encourage and acknowledge student contributions. Provide opportunities for them to share resources that you highlight in new learning contexts.

- Make regular check-ins with individual students via email or phone to privately provide gentle and firm guidance. Ask if there is anything you can do to help as soon as you notice a student is falling behind.

- Vary your source of content to demonstrate the breadth of the field and to provide multiple means of learning.

- Diagnose misconceptions, confirm understandings, and summarize discussions, pulling out key ideas that students have identified. Use this to inform your teaching and provide student agency throughout their learning.

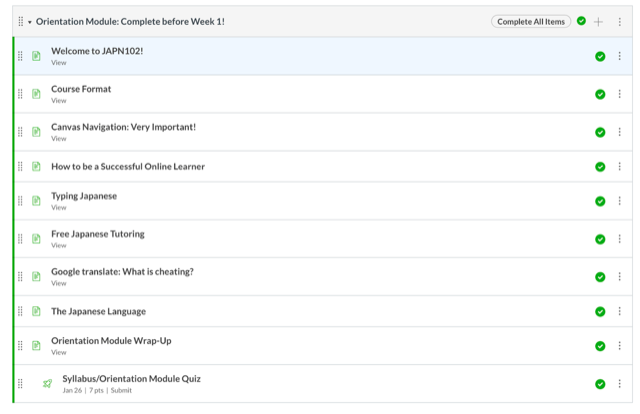

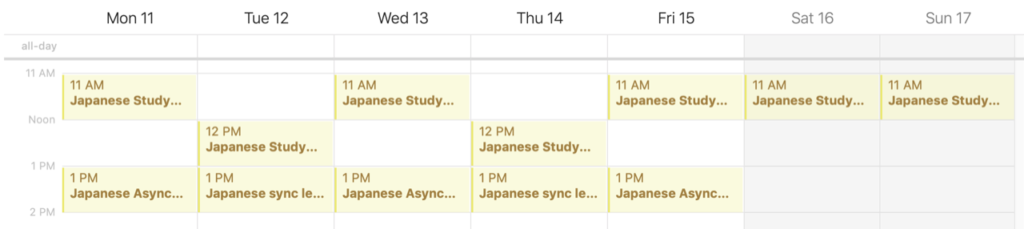

Clear communication and personal connections with students from early on are essential to establishing a strong online learning community and to building trust. Setting your students up for success from the beginning is an essential teaching practice in general. The need for support in an online course can often be greater due to the lack of physical presence to troubleshoot. Creating an orientation module (see Picture 7 above) for students to complete before the first day of the class is a great way to familiarize them with the content of the course and the technology you will be using, and at the same time to introduce yourself and provide them with the opportunity to connect with you for the first time. Depending on your LMS, you may be able to make this orientation module a prerequisite before any of the other modules become available. The module might include a welcome video message created with a screencasting tool (see welcome video picture below), syllabus and logistics. In addition, for language courses, including information on a policy for use of an online translator and how to be a successful online learner are helpful. As a wrap up, have students take a syllabus/orientation module quiz to verify that they are clear on the expectations, logistics and commitment necessary for the course. Adding additional open-ended questions such as “Do you have any questions about this class?”, “How are you feeling about this class?”, “ Is there anything that you want to tell me?” may also allow you to get to know your students better. Again take notes on each student that you can refer to later. It is also a good idea in online courses to require students to share a schedule that demonstrates the days and times they intend to work on your online course (See schedule Picture 9 below). This can be an assignment in the orientation module that gives them practice digitally submitting their work. The activities students engage in during the orientation module prepare them for the types of interactions they will experience with the content during the course. By understanding the mechanics of the courses at the beginning, the students are able to focus on the content of the course moving forward thus moving them towards deepening understanding. If later a student is not completing the work, check in with them and see if that schedule is working or if they need to adjust it and what other supports would be helpful.

Reaching out directly to students in these ways helps to build their trust in you and to see you as a connected instructor who knows and pays attention to each and every student. With this orientation module and initial communication, you will get to know your students pretty well even before the course begins. Continuing this communication by adding an open-ended question in online quizzes/assignments provides regular opportunities for students to reflect on their learning, to identify the muddiest points so that you are able to bring in additional scaffolding, and to share how they are doing or feeling about their learning.

Teachers can be visible in the class in various ways, through discussion posts, announcements and assignment feedback, to name a few. In fact, research has found that learners who received more individualized and content-specific feedback scored higher on a standardized exam and that they were also more likely to be satisfied with their learning experiences (Crisp, 2020). Here are some additional examples of teacher visibility and overall engagement in a remote classroom:

- Post regular announcements: A funny or cultural (for language courses) video that is related to a course topic along with a weekly overview/wrap up can go a long way in connecting students to the instructor and the content.

- Reply early and often to messages from students: Quick communication builds connection. But be clear from the beginning about the hours when you will be online so they aren’t expecting a response at 2 am.

- Use an announcement to share a student’s question and your response so that the entire class can benefit. The student who asked the initial question will feel acknowledged for the quality and importance of their inquiry.

- Use feedback to build relationships. Providing personalized feedback to let students know that their work has been reviewed can strengthen relations. Audio and video feedback is also effective in building a connection with learners.

Cognitive Presence

This presence is the connector between inquiry, critical thinking and building community. Once a climate of trust has been built as part of social presence, students will feel that they are in a safe enough place to ask questions that will build understanding and make the learning meaningful through connections to both content and to their peers. “Cognitive presence is the process of constructing meaning through collaborative inquiry” (Garrison, 2006). In order for the learning to be collaborative there must be a community with which to engage, and the engagement must be meaningful, including critical thinking and the processing of ideas to make meaning. A cognitive presence exists when students explore their own beliefs and ideas and connect those to the content, allowing them to make meaning. The support of the instructor in this process influences the students to deepen understanding.

Tips for developing Cognitive Presence.

- Provide numerous opportunities in a safe space for student inquiry. These spaces may include reflective questions at the end of an assignment or quiz, email, virtual office hours, discussion boards, and any number of other technologies you incorporate.

- Ask learners to identify their learning goal(s) for the course and continually reflect on their growth.

- Encourage the analysis of ideas through challenging and probing student responses.

- Have students share small group discussion summaries focusing on core concepts and learning outcomes.

- Develop learning activities that are authentic, challenging, collaborative, engaging, and relevant to building deeper connections between one’s current knowledge and course content.

- Facilitate reflective discussions and the sharing of thoughts and questions with peers.

- Ensure that project outcomes are relevant, meaningful, and applicable to future learning.

- Encourage learners to apply what they are learning to real-world situations.

- Integrate group learning to build collaborative knowledge and to solve problems.

Here are some examples of cognitive presence in an online course:

- Have students create their own discussion forum or Flipgrid to post ads looking for a roommate. Then based on the ads posted, choose with whom they would like to live and explain why they would be the perfect roommate.

- Have students look for an alternative spring break humanitarian project working in groups to research and plan it. Provide sufficient parameters based on their language level.

- Provide a Q&A forum where students seek assistance from each other on course-related questions rather than always posing them directly to the instructor. We all learn best by teaching others.

Figuring out how to create a learning community is always a challenge. All the tips in this article work whether you are teaching face-to-face, online, or blended courses. So, building a community in online learning environments doesn’t have to be as daunting as it may at first seem. By recognizing the critical importance of social, teaching, and cognitive presences, and by employing a variety of strategies, teachers can build a strong online community. Using technological tools alone and technology itself will not make magic – your personal touch and humor are the key ingredients. Don’t forget that you are a vital member of the community too .

Resources

Anderson, T., L. Rourke, D.R. Garrison and W. Archer (2001). Assessing teaching presence in a computer conferencing context, Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks 5 (2). https://olj.onlinelearningconsortium.org/index.php/olj/issue/view/101

Boettcher, J. (n.d.). Designing For Learning. Retrieved from http://designingforlearning.info/ecoachingtips/

Crisp, E. (2020, June 1). Leveraging Feedback Experiences in Online Learning, Retrieved from

https://er.educause.edu/articles/2020/6/leveraging-feedback-experiences-in-online-learning

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (2000). Critical inquiry in a text-based environment: Computer conferencing in higher education model. The Internet and Higher Education, 2(2-3), 87-105. https://www.sciencedirect.com/journal/the-internet-and-higher-education/vol/2/issue/2

Garrison, D. R. (2006). Online collaboration principles. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 10(1). Retrieved from onlinelearningconsortium.org/sites/default/files/v10n1_3garrison_0.pdf

Garrison, D.R. (2009) Communities of Inquiry in Online Learning, in Rogers, P.L. (Ed.) Encyclopedia of Distance Learning, 2nd edn, pp. 352–355. Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

McAndrew, A., Dykeman, T., Fell, C., & Nussbaum, B. (2018, October 25). Unpacking the Student Experience in Large Lectures. Retrieved from https://er.educause.edu/blogs/2018/10/unpacking-the-student-experience-in-large-lectures

Peacock, S., & Cowan, J. (2016, September). View of From Presences to Linked Influences Within Communities of Inquiry: The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning. Retrieved from http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/2602/3861

Thanks to all this information and tips. I’ve been a language teacher and now a business program instructor. Great to be reminded of tips and some useful strategies of how to provide a sense of community online – the challenge for me is to apply them in my current context where the parameters are very different. Good news, I am inspired. Thanks.

Very helpful- I’ very new to blended learning.

assign small study groups. Students can choose to join a group by the color they like, for example.

Create a Wechat group for the class.