Checking Reading Comprehension Remotely Using Student-Designed Comics

By Carol Anne Costabile-Heming, Professor of German, University of North Texas

DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.69732/GVZQ9864

Introduction

The shift to emergency remote instruction halfway through the spring 2020 semester forced all of us to pivot our instructional approaches without a lot of training. In order to ease the burden and lower the anxiety of students enrolled in my advanced German culture class, I made no major revisions to the course syllabus. I instead changed how my students and I interacted with the text under discussion to accommodate the new asynchronous learning environment. Despite the new format, I did not want to forgo the high level of engagement that students had demonstrated in the course thus far. While much attention has focused on techniques for engaging learners in presentational and interpersonal modes of communication in remote instruction, less attention has been given to the interpretive mode. In this article, I share one technique I employed in an advanced German culture class to help me gauge learners’ reading comprehension.

Course and Text Description

The course in question is German 3045: The Berlin Wall, an in-depth analysis of the Berlin Wall and its legacy. It is a culture-based course taught in German for students who at a minimum had successfully completed intermediate level language instruction. By the end of the course, students should be familiar with the history of postwar Germany, gain knowledge about divided German society by exploring life on both sides of the Berlin Wall, become familiar with portrayals of the Berlin Wall in literature and film, explore Wall art, and examine current practices of memorialization. The last three weeks of remote instruction focused on the short novel, Der Mauerspringer (The Wall Jumper), by Peter Schneider.

Written in 1982, Der Mauerspringer reads as both a historic and prophetic homage to the concrete barrier that divided the city of Berlin for 28 years. In a series of vignettes, readers encounter characters from both sides of the Wall, as they confront the effects that the Wall has on their lives. Each of the characters manages to traverse the physical barricade at least once, and these border transgressions occur in both directions. It is both a funny and poignant portrayal of the ingenuity of the human spirit that refused to be caged in. It also reveals the emotional scarring that the Wall caused. Though written some seven years before the Wall fell, Schneider presciently predicted that the “wall in the head” would remain long after the physical barrier had disappeared.

I include this text in the course because it views the Wall from multiple perspectives and does not present either East or West as a victor. Indeed, it highlights precisely how every Berliner was a victim of the Berlin Wall in some fashion. Despite the inclusion of short episodes, the text does pose some comprehension difficulties for students, especially those for whom this is their first encounter reading book-length fiction. The difficulties for students derive primarily from the fact that the book does not follow a linear format; they must pay attention to both time (because of a series of memories/flashbacks that the narrator introduces) and place (because the narrator also regularly crosses the border legally). Three characters, a former girlfriend (who grew up in the East), the narrator’s friend Robert, who chose to leave East Berlin and settle in West Berlin, and another friend, Pommerer, who lives in East Berlin and whom the narrator visits several times during the course of the novel, serve as foils to the narrator’s rather Western-biased views. The book is an excellent summative text for the course because it brings together the historical, ideological, philosophical, and artistic viewpoints that students had engaged with throughout the semester.

Assignment

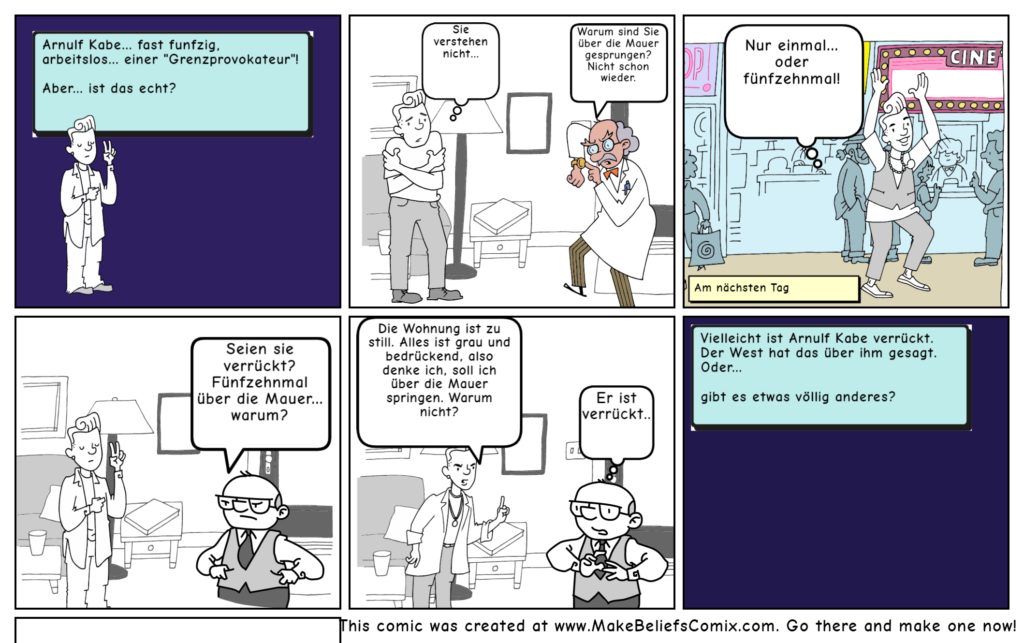

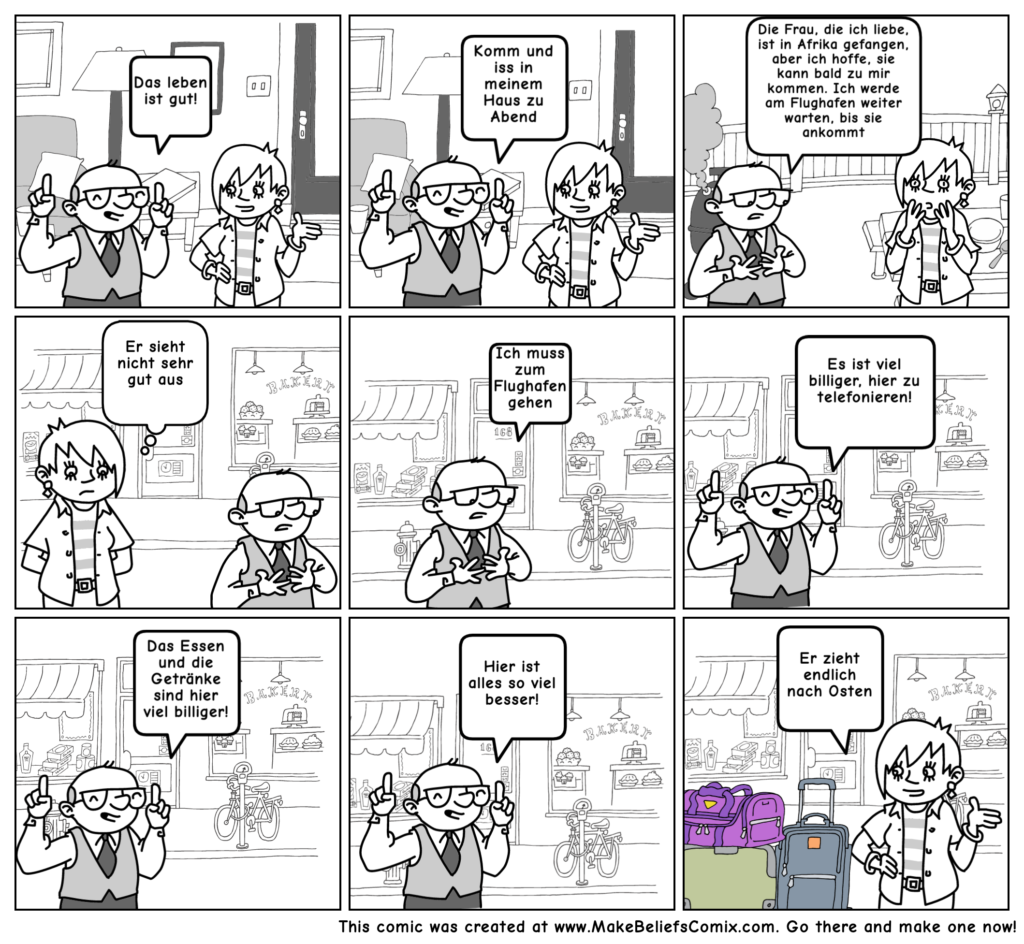

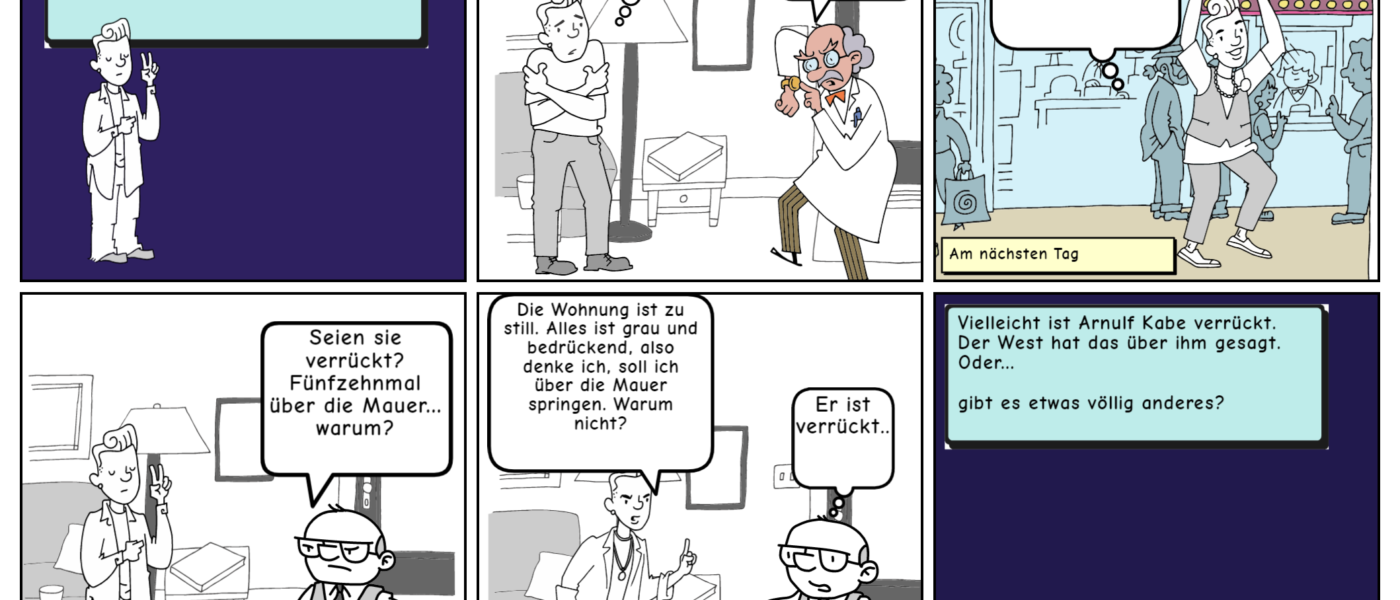

Prior to the switch to remote instruction, I had planned for students to create a comic strip based on one of the vignettes using the site “Make Beliefs Comix” (https://www.makebeliefscomix.com/Comix/). Originally conceived as a homework assignment that would be submitted to me electronically and then projected and discussed in class, I reworked the assignment into an online assignment to be posted to the discussion board inside the course LMS. In the assigned reading, students encounter Gerhard Schalter and Herr Kabe, the first two wall jumper stories that the text presents. The assignment asked students to retell the story of either Schalter or Kabe as a comic strip, and post a link to the comic to the course discussion board. Given the unexpected switch to a remote learning environment, not all students participated regularly. Eight students created a comic strip by the assigned deadline; half of the group created a comic about each character. After the deadline had passed, students were tasked with reviewing all of the comics posted by their classmates. They were instructed to pick one comic about each character (Gerhard Schalter and Herr Kabe) that they thought best captured the story of the character, and post a brief comment to the discussion board explaining what they liked about that particular comic strip. While there was an overwhelming favorite, all students received some comments from their classmates.

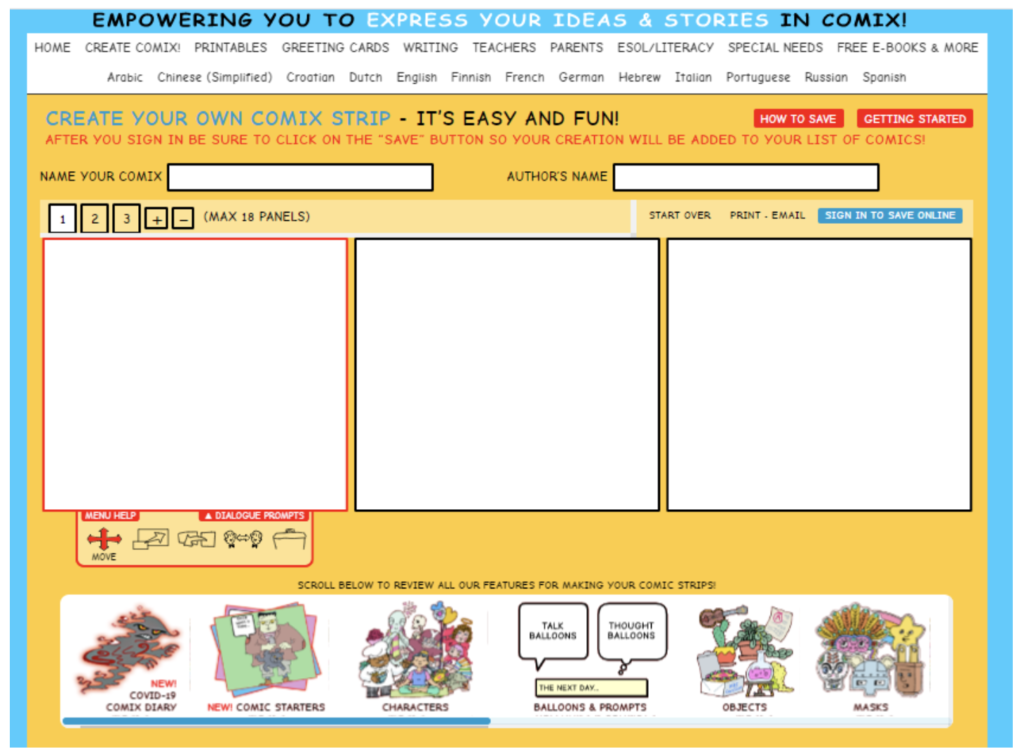

I used the website “Make Beliefs Comix” available free of charge at https://www.makebeliefscomix.com/Comix/. The site is user friendly and compatible with Windows and Mac operating systems, iPads, and mobile devices.

The site accommodates a comic of up to 18 panels; users choose the characters, backgrounds, objects, and speech and thought bubbles. The completed comic can be saved to the site (free of charge) as well as printed or e-mailed.

At first glance, this might seem like a simple assignment, but it requires higher order thinking. It required students not just to understand the story of the character in question, but also to apply this understanding by retelling the story in their own (German) words. Students did not just demonstrate reading comprehension; the assignment forced them to identify key details in the story in order to make the story fit the limited number of panels available. The comic strip would only make sense if the students captured the important details of the story. Though the subject matter of Der Mauerspringer is quite serious, the vignettes about Gerhard Schalter and Herr Kabe are light-hearted, making them particularly well-suited to depiction by a playful genre like a comic strip.

Student Work Examples

Analysis

My original plan for face-to-face instruction involved students working in groups to review the comics, voting as a group for the comic that they thought best captured the essence of the story, and presenting their findings to the entire class. I assumed that the comic strips would generate discussion, and would help students realize how well they understood the reading assignment.

In the remote instruction environment, students posted their comic strips individually to the course discussion board. As the instructor, I could quickly gauge the level of their reading comprehension. This was particularly important because these two stories were the first wall jumper descriptions in the book. It was critical that students were able to recognize them as complete stories within the larger narrative framework. All students demonstrated that they had understood the story. Moreover, because the speech bubbles limit the amount of text the students could include, the students were not able to copy blocks of text from the book. Instead, they were forced to rewrite what they had read. Variations occurred based on the student’s level of writing proficiency—students with more confidence in writing created comics that were more detailed. When students commented on each other’s work, they also reflected on how the comic strips captured the narrated episodes.

Reflection

For face-to-face instruction, I had planned for the student-generated comic strips to serve as starting points for classroom discussion. In the remote instruction environment, the comic strips served as a formative assessment of student understanding. The discussions posted to the discussion board were more thoughtful than I believe the class discussions would have been. In class, students likely would have focused on superficial comparisons of the comic strips. In this remote format, they engaged with one comic strip more deeply, reflecting on what elements made the comic strip an accurate and effective representation of the text they had read.

I intend to employ the use of student-designed comic strips in subsequent classes, because I think they are effective means of gauging reading comprehension and they encourage students to engage with the text more closely. In the coming semester, I plan to expand the use of these comic strips for longer reading assignments. Students will not only create their own comic strip based on an assigned reading, but will also exchange comic strips and continue or expand on them to create a collaborative representation of the text.

I love comics for working in class. They always prove to be motivating and attractive for students. I didn´t know about this website, but I will be glad to use it from now onwards.

I have been using MakeBeliefsComix for years. Easy for both teachers and students to use.

Have a look at another example:

http://www.leia.org/LEiA/LEiA%20VOLUMES/Download/LEiA_V2_I1_2011/LEiA_V2I1A07_Graham.pdf

Awesome! I will definitely use this website to increase students’ success in interpretive mode.