Literary Scavenger Hunts with GooseChase

By Carmen Granda, Amherst College.

By Carmen Granda, Amherst College.

DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.69732/LYRW3751

Around the halfway point of the semester, the classroom dynamic often changes with the arrival of midterm season. Many students, and if we are being honest, teachers, fall victim to “the midterm slump.” Students juggle studying for exams and writing papers–all while preparing daily for class. As teachers, we write exams, plan review sessions, and grade–all while creating solid in-class activities. Instead of fearing the “slump,” instructors can anticipate its arrival and use this time to try new ideas that will pique students’ interest in the material, breaking the monotony that often characterizes this time of year. Now, trying new ideas does not necessarily mean that as instructors, we have to create a new activity. It may simply require tweaking a pre-existing activity by changing its implementation with the use of a digital tool. One such tool that has become popular in the educational field is GooseChase, a digital scavenger hunt game that I first learned about while enrolled in the University of Colorado Boulder’s Emerging Tools in Practice course (Division of Continuing Education). After briefly explaining how to create a GooseChase account and game online, the second part of this article describes how game-based learning (GBL), in the form of a digital scavenger hunt, can be used to engage advanced Spanish students with challenging literature in a collaborative and creative way, build community, increase motivation, and encourage learning outside of the traditional classroom.

Scavenger hunts are a popular childhood game in which participants (either working individually or in teams) compete to complete a list of tasks or the most number of items on the list in a set amount of time. In variations of the game, participants take photographs of listed items or are challenged to complete the tasks on the list in a creative way. On the GooseChase webpage, educators create and facilitate a customized scavenger hunt that students access via the app. Once downloaded, students complete the tasks by taking photos or videos on their smartphones or tablets, a motivating and entertaining “twist” to the traditional scavenger hunts.

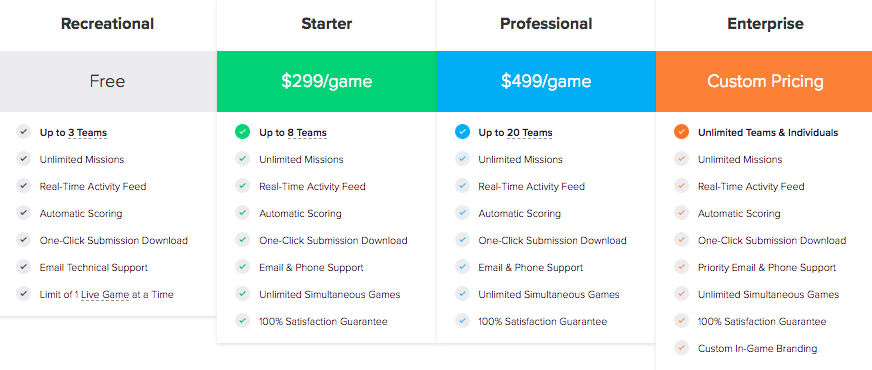

One of the great benefits of GooseChase is how easy it is to set up a game. As a game creator, you have four options that primarily depend on the number of teams desired: recreational, starter, professional, and enterprise. Instructors at the university level can also request a free license here.

With nine students in one writing section and eight in the other, I chose the recreational option, which allowed for the creation of three free teams: approximately five to six students on each team. Once you create an account and have signed on to their main page, you click on “New Game” on the right hand side to design the game. After entering the name and game objectives, you have the option of including a password and specifying the location. Once completed, press “Save and Continue.” Then, you create tasks, or “missions,” that you would like your students to complete. To make the missions more engaging, you can include links, photos, and videos that illustrate or record the task. Once completed, press “Add Mission” if you are ready to move on to the next. The new mission should appear under your mission list. Student submissions can include photos, drawings, and recordings, to name a few options.

As a creator, you can also assign different point values to each mission. High point values, for example, can be reserved for more complex missions that require students to go off campus or communicate with other students. Bonus points can also be added for exceptional and creative submissions and points can also be removed if students do not fully satisfy the submission requirement.

Submissions appear in real-time, and can be viewed in the activity feed, or grouped per mission or team. Once the game is over, the creator can download the submissions to use as prompts in class to guide discussion. Creators can also determine when the game begins and for how long it will last by clicking the “Start & Stop” button on the left. Times range from thirty minutes to seven days. Finally, once the game has been designed, it is saved in the owner’s personal collection, “My Games,” so it can be reused or modified in the future.

Not only is it easy for instructors to set up a game online, but for participants, it is also easy to download the app on their smartphones or tablets. The GooseChase website provides clear and simple instructions for students to access the game once it is downloaded on their electronic device. If students don’t have a smartphone or do not want to use their personal phone for this activity, they can share a phone and work together to complete the tasks. From a Spanish teacher’s perspective, working in pairs or small groups on these missions works 21st century skills, such as collaboration and negotiation — all in the target language.

With the “midterm slump” in full force early March at Amherst, I decided to use GooseChase for the two sections of my advanced composition course to review Julio Cortázar’s short story, “Casa tomada.” Two class days are dedicated to this reading: the first day is a general comprehension of the text and the second day we study the author’s use of time and space. To guide students through assigned readings, I provide them with a set of questions for homework. The pre-reading questions prompts students to research the author’s biography, different historical periods, and literary movements. Then, I usually assign them several comprehension questions that deal strictly with the text. Finally, I include 1 or 2 post-reading questions that require more reflection. This variety of pre-reading, reading, and post-reading activities engage students with the text while guiding them from comprehension to analysis and interpretation to production. Now, although these questions are useful, the format is very traditional. For this reason, GooseChase was an appealing option mid-semester: I could convert many of these questions into “missions.” In total, I created eleven missions, some of which I include below. The original missions are written in the target language, but for the purpose of this article, I have translated them into English:

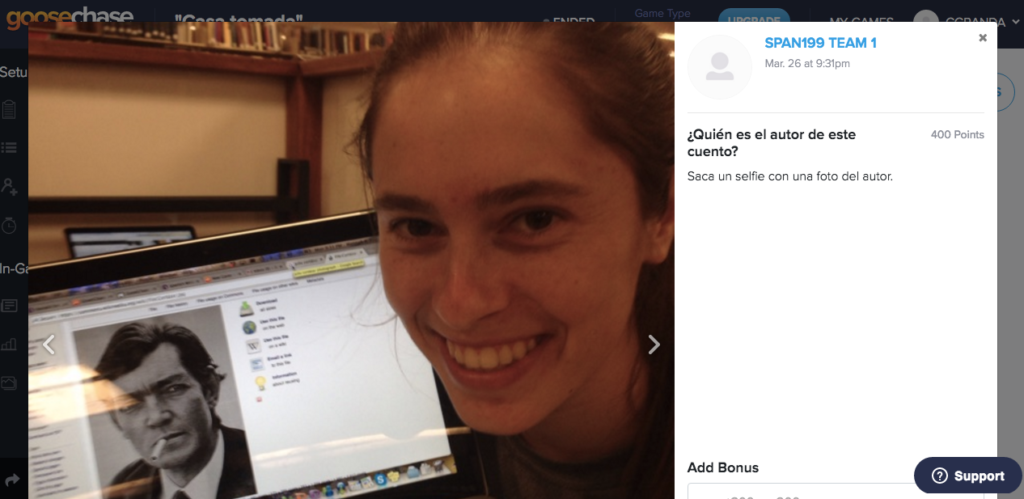

- Who is the author of “Casa tomada”? Find a photo online and take a selfie with him.

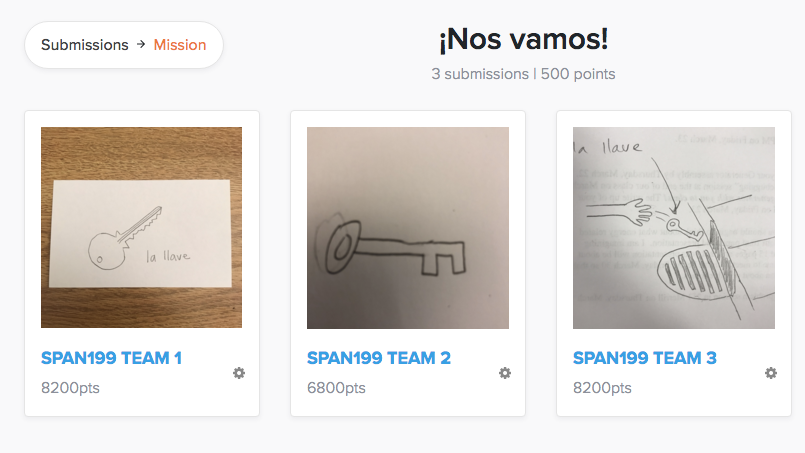

- When the two protagonists leave their house, they throw a ________ into the sewer. Draw this object on a piece of paper and upload a photo of it.

- What is the relationship between Irene and the protagonist? Take a photo of two Amherst College students who have the same relationship as Irene and the protagonist.

- Where does the protagonist go to buy books? There’s one in the town of Amherst. Take a selfie at this location.

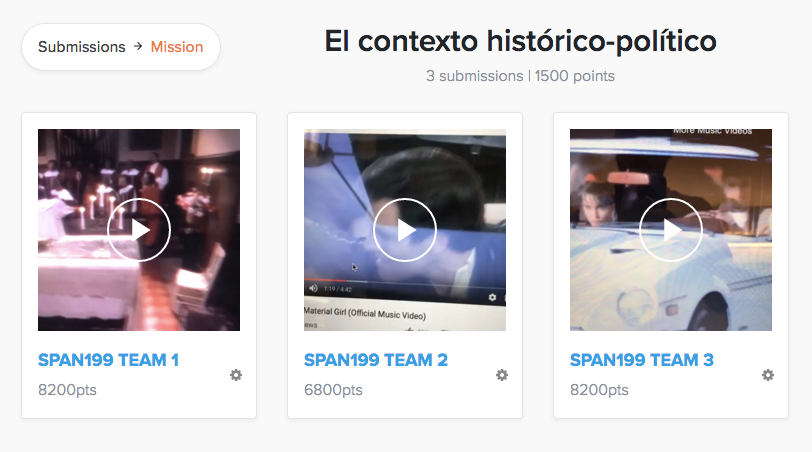

- When this story was written, Juan Perón was in power in Argentina. He was married to Eva Perón. In 1996, Evita, a film on Eva’s life and Argentina during the early 1950s, was released. The protagonist of this movie is a famous singer. Look for one of her most famous songs on Youtube, record a brief clip, and upload it.

To make the Cortázar game more exciting, I pre-created teams, dividing the two sections of the course into three teams in total (so 2 groups of 6 students, 1 group of 5). This meant that students from both sections could be on the same team, thus creating an opportunity to further build community outside of class.

Students responded enthusiastically to the GooseChase activity. In the survey that I administered at the end of the semester, many students noted the app’s ability to trigger “a deeper level of engagement with the text” and to “create new associations and memories that encouraged deeper understanding by stimulating different senses.” In part, this increased engagement and understanding of the text comes from the contextualization in a real-life setting that the game offers, as one student noted: “the activity helped contextualize what was otherwise a somewhat odd/fantastical text to a more grounded real-life setting. The questions prompted specific areas of comprehension within the text, which helped me get a sense of what was significant in the text.” In addition, the questions also gave students the opportunity to view the text in a creative lense, as one participant noted: “I found that the app helped me engage more with the text [ . . . ] because it urged me to use my imagination and try to interact with the text in creative ways.” Creative thinking is an invaluable skill that often disappears in college classes, but this faculty is important for tackling problems and developing solutions. In sum, the playful design and innovative missions not only motivate students, but also help them attain a richer comprehension of the course material and develop their creative thinking skills.

The creative quests and visual aspect of the scavenger hunt further contributes to students’ retention of the material and encourages them to frequently return to the game. One student shared that the game “prompted [her] to begin reading the assignment earlier and thus spend more time on it because [she] wasn’t rushing to finish before bed late at night.” Another student commented on the “cultural connections” that several of the questions touched upon and that helped “form memories about the literature that would last” beyond her time in Amherst. A submission that required students to upload a selfie with the traditional Argentinian drink, mate, for example, speaks to this increased level of cultural engagement. Furthermore, as Bradley E. Wiggins (2016) has pointed out, digital games help students retain knowledge (19), in large part because of the images: “The introduction of games or game-like elements into classes can also help the students to get a better understanding because they excel in visualizing complex concepts” (Hutzler et al. 2017, 156). That is, the images succeed in helping students engage with the material in an interesting way, as one student explained, “I am a visual learner, so looking at all the images for the game was very useful for me in learning the material.” It is clear that the old-school model of passively learning facts and writing them out for homework is no longer sufficient to prepare students in today’s world. Solving problems requires that students have fundamental skills, like reading, and 21st century skills, like teamwork, problem solving, research gathering, time management, personal and social responsibility, creativity, strong communication skills, and the use of digital tools. Taking photos and drawing images related to the text are two more ways that students can take on a more active role in the learning process.

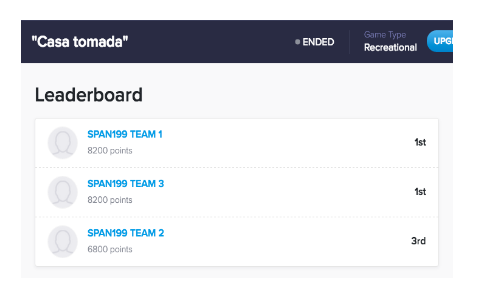

Adding playful game design features such as “points” and “leaderboards” can make such experiences more entertaining and motivating. This form of gamification encourages users to interact with the game voluntarily and repeatedly come back to it. In addition, since there is a possibility to create teams with GooseChase, the motivating factor increases significantly as they are competing against each other, creating “enthusiasm through friendly competition and teamwork,” as one student noted in the survey. The playful elements of digital games aims at the competitive nature of students as one student recalled: “. . . seeing other teams completing the game motivated me to try and complete the game as fast as possible.” The visual aspect of the leaderboard also acted as a huge motivator: “Seeing how many points the other teams had already earned encouraged me to do the same for my own team.”

According to Zoltan Dornyei (1994), group cohesion and classroom goal structures, which can be competitive, cooperative, or individualistic, are two aspects of L2 motivation (279) that I believe align well with the objectives of game-based learning. Dornyei proposes that the motivational component present in group cohesion speaks to the team’s desire to succeed as a whole (278). Indeed, in some cases in our “Casa tomada” scavenger hunt, motivation to participate came primarily from the team members, as one student reflected: “as soon as I saw that my teammates were getting engaged, I felt motivated to join in to help our team win.” Another student observed that he “was more motivated by [his] own team’s participation ([he] would feel bad if [he] didn’t complete [his] share).” In a cooperative activity, such as a group scavenger hunt, each member of the group shares responsibility for the outcome of the activity. For this reason, cooperative learning is highly regarded among L2 instructors and scholars as it promotes “intrinsic motivation [ . . . ], positive attitudes towards the subject area, and a caring, cohesive relationship with peers and with the teacher” (Dornyei 1994, 279).

Finally, with GooseChase, learning extends outside of the classroom. Mobile applications like GooseChase allow teachers to take classes outside, into the community. In the case of the Cortázar game, students reached out to other Amherst College students to complete missions and also found themselves taking pictures in town to complete their homework. In this regard, game-based learning via mobile applications permits students to “flexibly shape their own learning process” (Hutzler et al. 2017, 156). Having students engage with course material outside of the classroom, forcing them to “get out of Frost, [the college library],” as one student noted, and their dorm rooms to complete a homework assignment as part of a team mission, is a surefire way to increase motivation and engagement. As one student explained in the survey: “One of the benefits was that this app encouraged us to work with our peers outside of a classroom setting, which is always beneficial in an academic environment.” Students are pushed outside of their comfort level by visiting off-campus spaces to complete creative tasks with the help and support of their team.

Although the activity exceeded my expectations in terms of increasing student engagement and building community, if you are considering using it in your course, I would like to share a few of my thoughts and additional reflections from students:

- In my game, each team member had to post at least one submission. In part, I chose this format to make sure that everyone on the team participated. In reality, there’s no way to control who did and did not post. This is something to keep in mind when designing the game and writing the instructions.

- One student suggested that the missions include at least two options as submissions, keeping in mind students’ different learning styles.

- All of the students who completed the survey suggested using GooseChase more frequently–at least three times during the semester. Many also recommended keeping the same teams throughout the course and transforming the game into a semester-long friendly competition.

As with any digital tool used in an educational context, there should be a clear learning objective when using an app for a course. I would not use this program for very difficult texts, and I also would not use it often, as the novelty would wear off. Nevertheless, GooseChase was an excellent way to end the first half of the semester. Its user-friendly and intuitive interface allowed students to focus on learning, engaged them with the text in atypical spaces on and off campus in a creative way, and built community. The GooseChase website has a game library that I encourage instructors to explore if you would like to implement the program in your language classes, during field trips, and for staff team-building opportunities.

REFERENCES

Dornyei, Z. (1994). “Motivation and Motivating in the Foreign Language Classroom.” The Modern Language Journal, 78(3), 273-284.

Hutzler, Armin and Rudolf Wagner, Johanna Pirker, and Christian Gütl. (2017). “MythHunter: Gamification in an Educational Location-Based Scavenger Hunt.” Beck D. et al. (eds) Immersive Learning Research Network. iLRN 2017. Communications in Computer and Information Science, 725. 155-169.

Wiggins, B.E. (2016). “An Overview and Study on the Use of Games, Simulations, and Gamification in Higher Education. International Journal of Game-Based Learning, 6(1), 18-29.