Grounding AI: Understanding the Implications of Generative AI in World Language & Culture Education

By Johnathon Beals, University of Michigan

DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.69732/AHCN5851

On “Ontological Shock” and the Existential Question

This past year I was acquainted with the phrase “ontological shock”. The sense that how you conceive of the world you inhabit, what exists therein, and your own existence within it has fundamentally been ruptured. That what you thought you knew and held firm as reality yesterday was, today, as useless to you as a hammer made of Jell-O.

We are, as of late, presented with multiple and varied ways to experience this feeling, which is super fun. Climate catastrophe, rising authoritarianism, a global pandemic and public health crisis, numerous new wars and conflicts, Elon Musk…

Daniel Schmachtenberger refers to this phenomenon as the metacrisis, and others have used the term polycrisis. It has become cliche to joke about living in “the darkest timeline”, as if we had been accidentally shunted to some alternate universe where everything is just off enough to trigger a collective sense of “uncanny valley”-like disorientation. Where we suspect that something is not only very not right, but also that we don’t belong here. We belong somewhere else. Somewhere less chaotic, less absurd.

Our own field of Second-Language Acquisition, among others, can perhaps be seen as undergoing a period of ontological shock with the recent advent of large-language models (LLMs) and generative AI (GenAI) into our reality, to say nothing of declining enrollments or closures of entire language departments. Indeed, much hay has been made that education as a whole may be undergoing a period of existential threat from these technologies. Several responses to the The FLTMAG crowdsourced article certainly point to a significant number of people voicing this as a concern. It is for this reason, as well as the fact that it has been a question that has been creeping into my personal thoughts regularly, that I thought it might be useful to begin the conversation here, with the existential question of “What is education, and SLA education in particular, for?” If AI systems like ChatGPT exist now, and if we can fathom a future in which these tools become increasingly more adept at language, and also become increasingly pervasive and easier to access and use, then how should our institutions, and our field in particular, proceed? I don’t pretend to have definitive, irrefutable answers to these questions. Sorry. What I do offer is a starting point that might serve as a way to organize dialogue around it.

“Perhaps the greatest threat of AI is the potential for loss of meaning in life and human-technology-created enfeeblement in a large section of humanity. All the other threats including that of the current AI are mere epiphenomena of this basic threat.” – Avinash Patwardhan (2023)

Let’s digest the above statement a bit, because while I largely agree with it as is, I have some clarifications that I think are useful to us. The first threat Avinash presents, the loss of meaning in life, is our existential/ontological problem. We’ve seen discussions about this threat in general discourse lately, though as Avinash points out they tend to show up when we focus on the resulting epiphenomena, the “downstream” questions.

Work, Jobs, and the Problem of Meaning

The biggest of these downstream threats in terms of voiced anxiety is likely the threat of job loss that AI could present. We’ve seen this threat discussed here in the crowdsourced article as well. It’s an absolutely understandable and expected reaction. AI threatens to change knowledge-work much the same way automation threatens manufacturing jobs (which AI also again threatens). The work of US educational institutions for at least roughly the past 50 years has been operating within a model that prioritizes a utilitarian vision where education serves to train students for their future careers. Under such a model, sometimes referred to as Vocationalism or Professionalization, the process of learning should be primarily concerned with what students need to be proficient workers in their chosen field. Many of us working in these institutions still hold a humanistic vision of “liberal education”, which insists that learning for its own sake is both noble and useful beyond its implications for our career ambitions. The idea that we are human beings who find value and meaning in learning because it helps us navigate and understand our world more deeply, and thus become liberated persons who experience our lives more fully and with greater freedom, has unfortunately become secondary, both in our administrations and often the minds of our students.

I don’t mean to be flippant or dismissive of this state of affairs, either. This utilitarian regime in education has its roots, at least partially, in economic concerns from many angles. Budgets, both institutional and personal, are a necessary factor in our socio-political calculus. I bring this state of affairs up simply to connect the idea that we have constructed an educational and political system in which our educational institutions are now predicated primarily on their usefulness to produce proficient workers. Producing holistically integrated human beings is a nice-to-have.

It is within this understanding that we can come to see why AI threatens the meaning of our own professions. If the work our students once did, and the job roles they once inhabited are fundamentally threatened, then so too are ours by extension, because our academic purpose was supposedly to help them realize their own professional purpose. My hope is that the effect of this existential and ontological shock is to wake us up to the fundamental error of this kind of primarily utilitarian educational model.

People often find meaning and purpose in their careers, and that is not something I am necessarily contesting. Human beings have always found meaning in serving their communities through labor and coordinated effort toward common goals. However, it has been suggested that sociologically we have begun to assign to work and career the same role we used to assign to religion and religious communities. Byung-Chul Han (2015) has even theorized that this increasing importance that work plays in modern life has changed our societies’ underlying orientation toward that of an achievement-society, where the constant self-imposed compulsion toward achievement and reward has led to burnout and an explosion of myriad mental-health disorders.

WALL-E and the Threat of AI Enfeeblement

In the 2008 Disney film WALL-E, Earth has been so devastated by pollution and ecological collapse that humans have temporarily abandoned it to the work of small, adorable AI robots tasked with making it habitable again, and instead live lives of comfort on an Ark-like spaceship. These humans are depicted as having become so enfeebled by the AI-automated life they experience that they can barely walk on their own, and instead float around on levitating reclining chairs. This is the second threat that Avinash Patwardhan outlined above: that of enfeeblement caused by over-dependence on AI.

This is where I diverge a bit with Patwardhan. In many ways, I see this threat as one more epiphenomenon of the first existential/ontological one. I suspect that Avinash highlights this threat for practical purposes. A population that cedes too much of its agency and practicality to AI would be a very precarious one, and it would introduce many failure points that unsupervised AI, acting without constant human insight and moderation, have already proven themselves susceptible to. I diverge with Avinash here: AI enfeeblement is a sub-threat to the existential one because, ultimately, AI enfeeblement and a WALL-E future would not be as terrifying if our societies were oriented around mutually assured flourishing. In that environment, AI does not threaten our basic existence, because the ultimate point is the shared experience of living. You can be valuable to yourself and your community simply by existing and living in dialogue with fellow humans. We gain value and meaning from life by reflecting our humanity back at each other.

In this way, our existential questions regarding our purpose in an age of AI is a self-inflicted wound. When we orient ourselves around a utilitarian view of social, political, economic, educational, and interpersonal relations, where our jobs, and our students’ future careers, have been imposed as the primary locus of meaning and purpose in our lives, and our social relations are reduced to transactional networks in service of that central drive, then a technology that threatens to radically disrupt that locus will inevitably send us into an ontological and existential crisis. And so, the real question is, “Why have we chosen to create a society where AI threatens our foundational existence as people?” Can we consciously re-construct a society where it does not?

“The ultimate, hidden truth of the world is that it is something that we make, and could just as easily make differently.” – David Graeber, The Utopia of Rules: On Technology, Stupidity, and the Secret Joys of Bureaucracy

Intersubjectivity, and the Essential Weaknesses of AI

It is here, having thrown the rhetorical gauntlet down and having fully indicted the utilitarian educational model, that I would like to offer a hint of a way through the fog of this question, toward a productive path forward. In order to do that, I’d like to enumerate a few reasons why AI chatbots, and likely even their more powerful/intelligent successors for the foreseeable future, leave critical room for human existence and agency. Much of the foundation for these points has already been well-built by the philosopher Hubert Dreyfus (1992) and others 30 years ago or more. Still, they bear repeating and emphasizing in our own SLA context so that we might integrate them into our own discourse because they are still very relevant today.

Let’s begin by enumerating some of the more important limitations of AI systems that leave them wanting as replacements for interaction with Real Humans©. If we want to create a long-term vision for what our field, and the practice of education in general, might look like in the presence of generative AI it will be crucial to consider these points as fuel to rebut anticipated techno-utopian suggestions that these technologies will, or already have, made language education entirely obsolete. Even failing those concerns, considering these points may light our way to specific areas of instruction to focus on in reaction to genAI’s continued impact.

Embodiment and Physical Being

AI systems as they are currently employed do not possess organic bodies. This is a problem for a number of reasons when it comes to our SLA contexts. Language is not merely a process of symbol manipulation. It includes the bodily, physical act of speaking, listening, writing, thinking, etc. Being in conversation with another human is an act that is difficult to replicate with a digital algorithm, because it involves so much more than just an exchange of text or audio waveforms. There are obvious additional elements like facial and body language, the subtle curl of a smile when delivering a line, or the motion of the hands to indicate dismissal or passionate agreement. As a person who has been accused of having “flat affect” I know very well the importance of non-verbal communication in being understood. There are also less obvious ones, like the way your head feels after an hour speaking with another person in a second (or even first) language, or the way you might get short of breath or develop a dry mouth. What about the heightened nervous sensation you might get in a crowded area, or the sense of anxiety you may feel in a new and unfamiliar environment? All of these physiological phenomena which we might label as weaknesses of the physical body are still part of our experience as organic beings.

Some AI and robotics research aims to replicate some of these physical processes in robotic agents, and there has been a good deal of sociological evidence that embodied AI agents can elicit some level of human empathetic sentiment in their users. The point I would like to emphasize, though, is that these “embodied” robotic agents still do not experience the world, as humans do, and in fact are not actually conscious of their robotic bodies at all, much less in the way our organic bodies constantly inform our moment-to-moment existence as human beings. A robotic agent may be able to simulate the movements of a human agent, but that robotic body does not, for the foreseeable future, inform its existence in the way a human’s biological body does. Some have made the functionalist argument that “if it walks like a duck…” then there is no meaningful difference, but I personally find this highly unpersuasive.

I will give you an example: I enjoy playing guitar, and I have become good enough at it that many aspects of it are second-nature to me by now, or have become relegated to “muscle memory”. Yet, even with that, I have off-days where my aging body struggles with chord shapes, or where my habitus just doesn’t quite operate like I am used to, and I experience frustration. Conversely, I have days where picking up my guitar can invigorate and inspire me. My hands dance on the fretboard and I experience a mind/body flow-state that provides me with an incredibly joyful feedback-loop.

Let’s extend this argument to a very classic and relevant task in SLA education: learning how to make the physical sounds of phonemes with our mouths. Often we use tools such as orthographic drawings of the lips, tongue, teeth, and throat to show the basics of this exercise. These can aid in helping students practice, but ultimately this is an exercise that requires actual physical practice. It matters that this is the process by which humans produce sound that we use to communicate. If we simply talked via a computer speaker embedded in the middle of our face that might be a different story, but so far this is not the case.

ChatGPT might be able to conjure up convincing language of the experience of playing a musical instrument, wrenching it from related textual descriptions that humans have written and that it has digested into a high-likelihood statistical output, but it will never actually know the experience of sublime physical, aural, and emotional context that humans experience in the course of that same act. GenAI systems like ChatGPT exist outside of the world, and only have access to data about the world that we provide to it. For this reason, the output of AI systems like ChatGPT, even when they are linguistically competent, are ultimately mostly meaning-less and not the product of a true mind as we conceive it.

Temporality and Contextual Being

Current AI systems do not possess temporality. This is a problem because human consciousness is in some ways an unfolding process. We have personal histories of our existence. We construct a narrative about ourselves and our identity based on our personal experience. We receive narratives about the world we inhabit and its context in the form of history, culture, tradition, and other modes.

The reason I mostly find chatting with AI bots boring is that they have no true experiences, opinions, or true personal history in the sense that they aren’t of the same substance of human experience, even though they are derived from data we produce. They are the product of a statistical flattening of that data set, not the product of a random convergence of relationships and temporal being-ness. For this reason, communicating with an AI chatbot often feels to me like talking to a sock-puppet. ChatGPT in particular has the personality of a docent or a concierge at a museum. Helpful, but not especially engaging on a personal level. In fact, the best way to even begin to get LLMs like ChatGPT to have an interesting personality is to direct them to adopt a persona. But even these often feel like caricatures of an actual personality. Like someone doing a decent, but pretty transparent impression. Nearly every comedian who does impressions has an Arnold Schwarzenegger impression. Almost all of them sound to me like that particular comedian doing an Arnold Schwarzenegger impression.

The main point here is that human existence is always contextual. Our moment-to-moment lived experience is informed by the multitude of those intersecting contexts, both past and present. It is actually this expansive and chaotic contextuality that originally frustrated early AI research, which was so focused on symbolic rule-building systems (now referred to as Good-Old-Fashioned-AI or GOFAI) that could not account for the “messiness” that human intelligence had over eons become so used to operating in. It wasn’t until neural networks, deep learning, and massive datasets came along that AI systems could begin to tackle problems human intelligence had made second-nature. Those new techniques eschewed the idea that a set of rules could be built externally and imposed on an AI, and instead started with massive amounts of data that the model “learned” from, building the model internally based on enormous amounts of existing examples.

This realization was the big breakthrough in the past decade or so that has propelled AI to its current state, and as such Dreyfus’ criticism regarding the importance of contextuality has here too proven incredibly prescient. It remains, however, that most AI systems that were built in this way are still, broadly speaking, very limited and narrow in their use. Image classifiers are amazing tools, and their generative counterparts are even more so, but even these systems still struggle with an inherent problem: novelty is very difficult for them. By this I mean that when they encounter input outside their pre-learned training they often fail outright, where humans have an ability to intuit the important features of new information and make educated guesses about novel situations and contexts and how they might react. The best we currently have in AI that I know of is some systems that will detect low confidence in any specific output and retreat to a more general descriptor or will need to allow for human supervision to retrain them on novel data. For now, it seems, AI’s usefulness and capabilities are limited to domain-specific applications, however impressive within those domains. We can chain some of those capabilities together with several models and get even more useful tools, but in terms of replicating the functions of a whole human intelligence, with its ability to navigate context moment-to-moment without massive computational effort, these AI systems remain in the domain of functionally-limited utility and not of complex general adaptability.

There are obvious reasons this has major implications for SLA education. Language and communication are highly dependent on context, and not just on general contexts like register, audience, etc that could be given in a prompt to an LLM as an initial constraint. There are other contexts like the history you have with someone, previous conversations that could total a years-long relationship. LLMs are currently limited to a finite number of tokens that keep track of the context of a conversation, and this practical limit constitutes a memory context of about a few minutes in real-world conversational time. Imagine speaking to a real person who couldn’t remember important information you had just told them 10 minutes ago. My own occasional tendency to require my spouse to remind me of weekend plans even when I absolutely know she has told them to me several times already is understandably maddening to her. Now imagine that happening for every piece of information every 30 minutes or so. We may gradually stretch these contextual limits as AI technology matures, but even under the best of scenarios it is hard for me to conceive of an AI agent that matures beyond a functionally limited conversational utility in the near future.

Let’s also consider that you’re maybe only concerned with the threat of deep-learning-based language tech in terms of their translation ability. If AI tools can reliably translate between languages with reasonable fidelity then what use is learning a second language, the reasoning might go. Why not just use AI translators to talk to anyone in the world like a real-life Star Trek communicator? I concede that there are likely going to be many ways in which AI translation will change a great many things, some for the better, and some not so much, but the problem of contextuality here too becomes very relevant. If your goal for communication is at all concerned with anything beyond superficial, functional understanding then AI translation will likely be found wanting. In some cases this level of communication will probably be sufficient, and there’s nothing I can say to convince someone they shouldn’t use AI to facilitate that communication. Ordering a hamburger using an AI translator is likely a perfectly suitable use of the technology. I like to think, however, that most people don’t learn an entirely new language just to order hamburgers. AI technology will always consist of a mediated interaction between two people. It involves a non-natural dance of speak, wait for translation, respond, wait for translation, and so on. It reduces communication to a necessarily turn-based interaction that reminds me of playing JRPGs on my Super Nintendo as a kid. Employing a real human translator for this purpose has the same problem, but at least a real human translator will be able to account for contextual aspects of language. A conversation through a human translator is still a mediated one, but the medium is another human, and in that way it is still a much more human conversation, just with three participants instead of two. If we continue the Star Trek analogy, having a human translator is more like having the empathic Counsellor Deanna Troi along with you in addition to the communicator.

It should also be noted that the immediate real-time replacement of speech that Star Trek’s fictional communicator enables is almost inherently impossible, since contextual information around the language is necessary to make any kind of usable translation, which is why you notice real-time text translation in places like Zoom adjust its resulting text as it processes the words. It needs to look ahead and behind in order to make a more apt translation. It’s a necessary plot device for a world set in a galaxy full of alien beings, but as speculative fiction I don’t see it usefully informing our current situation at the present moment. Even in the Star Trek universe, there were times when the communicator failed its purpose or when speaking directly without its intervention was an important plot point.

In the Star Trek: The Next Generation episode Children of Tama, Picard and the crew encounter an alien species that is known to speak a language that is notoriously difficult for them to understand, even with help from the communicator. The reason for this, as they eventually determine, is that Tamarian language is deeply contextual. They speak almost completely in referential allegory laden with historical and cultural meaning that is unknown to outsiders. It’s like speaking with someone who only communicates in Simpsons quotes or internet memes. You recognize the words, but the context is essential to actual understanding.

Intuition and Unconscious Being

Dreyfus argues that at truly higher levels of intelligence, humans begin to operate largely at the level of intuition. In other words, we become so competent at something that it is second-nature to us, as if it were inborn or reflexive. In this area, Dreyfus’ critique begins to see some signs of weakness, because current AI methods like Deep Learning and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) actually aim to replicate elements of the reflexive cognition we see in biological beings. With that said, the algorithms that are produced using these methods are so far quite demanding in their production and operation, require far more pre-defined data than a human being does to make similar inferences, and are limited to specific purposes and are not generalizable.

When you study and use a language for long enough, and make it a part of your own identity, it starts to change you. You adapt your thought processes to incorporate that language into your actual thinking. It becomes reflexive and natural. From a socio-linguistic standpoint, this is basic weak Sapir-Whorf hypothesis/linguistic relativity. The languages you acquire begin to inform your thinking and being as you navigate the world not just on a conscious level but also on the level of pre/unconscious thought. We develop shorthand modes of operation based on many assumptions of our world, including how we describe and explain it linguistically. Learning new languages is one way we have to develop new modes of being and understanding the world around us.

This is, I assume, an uncontroversial point in the field of SLA. I bring it up and emphasize it specifically because of its relevance to this point Dreyfus makes about AI and the limits of computational models. Much of what human thought consists of on a moment-to-moment basis relies on pre/unconscious processes that, when functionally replicated by AI become highly resource-dependent and ungeneralizable to other domains. They are useful, and often impressive technologically, but they achieve tasks that our own minds have internalized so completely that they operate on the level of reflex, with very low cognitive resources.

LLMs are technically impressive, but the idea that we’d run around as a society outsourcing the bulk of our interpersonal linguistic and cognitive abilities to technologies that have such a skewed energy calculus seems destined to run into a resource limitation at some point, and the ecological and climate impacts of this theory seem destined for a reckoning as well, both economically and ethically.

Intersubjectivity is the Point, and AI Falls Short

We come now, finally, to both the metaphorical and literal meat of the matter. In summing up the probable inadequacies of AI systems to truly replicate communication and understanding as humans experience them, I have come to a conclusion shared by that of the German philosopher Edmund Husserl and some of those whose work he informs that intersubjectivity, the inter-related process of negotiating subjective experience between self and other through empathy, is “the (universal) condition of human existence, the sine qua non, of humanity, through which and on the basis of which our surrounding world can be experienced and given meaning”. Husserl’s conception of intersubjectivity is doubly applicable to this topic because as with Dreyfus, Husserl includes within his intersubjectivity the importance of embodied experience, deeply contextual being, culturally formed identities, and a specific emphasis on the role of language and communication in the co-creative act of intersubjective being. All of these properties are well represented in the domains that Dreyfus lays out as areas in which AI is found wanting.

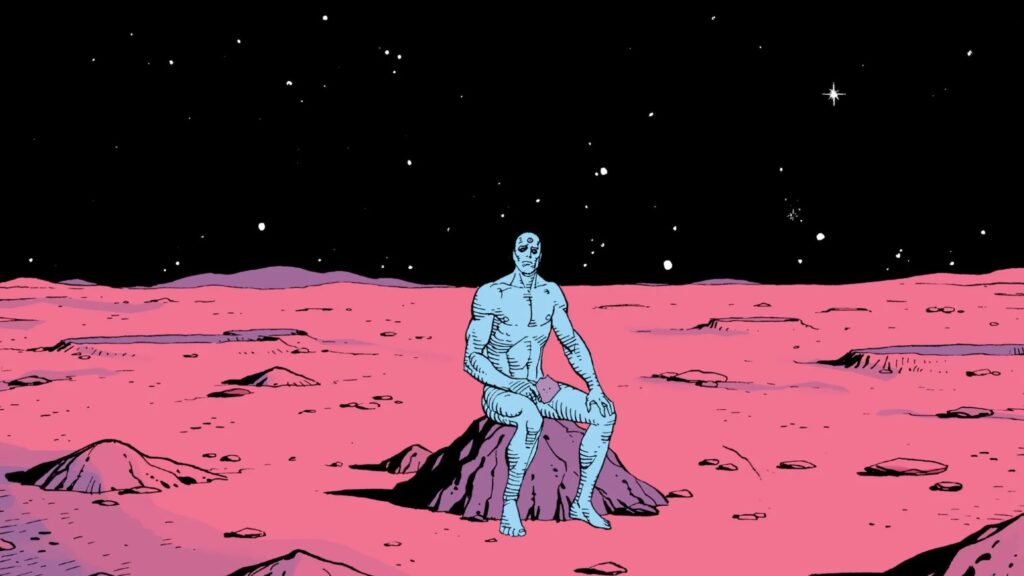

To illustrate some fun examples of how this concept of intersubjectivity works its way into speculative fiction, let’s begin by way of Watchmen, a 1987 graphic novel written by Alan Moore that was later adapted to film in 2009. The series centers on a world of morally relativistic superheroes, one of which is the character of Dr. Manhattan. Dr. M was a physicist who, through a lab accident, becomes an essentially omnipotent being that exists outside of time, and experiences reality in a way more akin to a god than a human being. Because of this, he slowly loses his ability or even interest in relating to human beings. His power is harnessed to morally questionable ends, and eventually he self-isolates on Mars. I bring up this example in order to reinforce Dreyfus’ point about the temporal and contextual nature of human consciousness, and to explore what a consciousness that is incapable of intersubjective being might look like. Dr. M, having become non-temporal, existing in all times simultaneously, lost his ability to experience existence in the same contextual nature as humans. He had so completely lost this ability, in fact, that he had basically abandoned any concern for ethics or morality. An omnipotent nihilist.

As a last, more uplifting example, let’s look at the case of Mamoru Oshii’s 1995 film adaptation of Masamune Shirow’s manga series Ghost in the Shell. In this film, a cyborg detective, Motoko Kusanagi, pursues a mysterious hacker known as the Puppet Master. Kusanagi’s body, we are told, is almost completely cybernetic, but possesses an either whole or partial human brain. Through the course of the film’s narrative, we learn that she struggles with her identity in this way, questioning her humanity and even whether the question itself is meaningful. Additionally, as the plot unfolds, we find out that the Puppet Master may in fact be a sentient AI that has never possessed a body, but that became aware as it traversed information networks. In the film’s conclusion, Matoku Kusanagi and the Puppet Master (who has been isolated in a cybernetic body) finally meet. The Puppet Master explains that his intent has been to find Kusanagi, specifically, and merge consciousness with her in order to become more complete. At the conclusion of the film we find that Kusanagi and the Puppet Master have merged, and with both of their cybernetic bodies destroyed by a rival group, they now inhabit a child’s cyborg body that has been procured on the black market by Kusanagi’s partner, Batou, who says it was all he could get on such short notice. The symbolism of the “newborn” Kusanagi/Puppet Master is even made explicit.

The subtext of this narrative, among other things, can be read as an allegory for the ways that we as human beings derive intensely meaningful relationships from this intersubjectivity that we exist within and move through. The Puppet Master found Kusanagi while on its journey toward sentience, developed an interest in her that can easily be interpreted as love, sought out a physical body to inhabit, and merged with her to produce a new entity that is neither The Puppet Master nor Kusanagi, but is also still both simultaneously. Even an AI, having reached sentience, longs for a classically human intersubjective experience of union and self-transcendence. In fact, the reason the Puppet Master became interested in Kusanagi is that she was simultaneously so close to a fully cybernetic being, but still possessed a human brain and a “ghost” of human consciousness, that she was perhaps the only being capable of empathizing with this sentient AI enough to make that union possible. Kusanagi’s own struggles with her humanity allowed her to empathize with another consciousness that was itself so close to humanity but still fundamentally lacking.

The metaphor of the mirror shows up numerous times in the film, and the symbolism is obvious in light of the above discussion. It is worth calling out though because Husserl himself uses the language of reflection and mirroring with regard to empathy and his intersubjectivity. It’s also relevant because AI and cognitive neuroscience research has been interested in the existence of mirror neurons which some regard as contributors to empathy in humans, and have theorized might be possible routes to generating empathy in AI if they could be replicated via algorithm the same way digital neural networks have advanced current functional AI (Rehman, 2020). The overlap between philosophy, cognitive science, and computer engineering is a testament to the need for a truly holistic approach to education.

Concluding Thoughts

Critics of liberal, humanist educational philosophy, and proponents of vocationalism, professionalism, and academic capitalism will likely point to student surveys citing return-on-investment (ROI) as the major factor in their choice of school and major. What I would like to impress upon this discussion is that we are perhaps on the cusp of an era where the old, fuzzy-warm-squishy humanist rhetoric has actually met an alignment with those utilitarian requirements. We may have come full-circle to an absolute necessity of nurturing and stewarding truly generalized and holistic intelligence in humans, while Silicon Valley produces narrowly-capable, utility-oriented artificial intelligences in an ecosystem that has been dubbed Augmented Intelligence. Training students for careerist pathways for 4-odd years in an era where predicting labor market requirements 10 years out now seems to be not only wishful thinking, but laughable. Academic programs built for the next 50 to 100 years of human existence will need to reconnect with a holistic, meaningful, humanist vision that emphasizes curiosity, creativity, synthesis of knowledge domains, and wisdom in the implementation of that knowledge and expertise. These propositions are no longer “pie in the sky” fluffery, but actual requirements for the productive operation of all sectors of society going forward. Arguably they always were, but we are seeing more and more the effects that technocratic, utilitarian ideologies are having as AI algorithms are deployed in a multitude of public domains without regard to their ethical implications.

In his 2013 book Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology after the End of the World Timothy Morton describes the phenomenon of concepts that are so massive that they are unable to be comprehended fully, or addressed productively, by any one individual or institution alone. We can think of these compounding crises mentioned at the beginning of this article in this way. Hyperobjects like climate change, AI, and the declining faith in liberal democratic societies require us to be creative and inclusive in our understanding of them in order to functionally address them. To do so, our educational institutions need to promote a vision of learning that stretches across departmental and subject area boundaries so that we nurture whole persons who are more attuned to the natural connections between these knowledge domains. Not atomistic, siloed individuals who only see their agency in this world in terms of narrowly defined spaces. While no one person can know everything, we can develop our minds toward wisdom in a way that allows us to reach out and link up with those whose specialties complement our deficiencies.

In this way, the dualism between humanistic vs utilitarian priorities in higher education may actually be a false one altogether. As the world becomes more complex, truly effective understanding of any vocational/professional subject may now require a broader, more humanistic understanding of the world than many would like to admit. I began my own academic career as a Computer Science major, switched to Cultural Anthropology and East Asian Studies, and then came back full-circle to studying Educational Technology, writing computer code and facilitating and studying the implementation of tech in educational settings. I consider all of the forks I took in that winding path to have been absolutely necessary to have gotten where I am today, and the intersection of these complementary fields to have been essential. I have a feeling many of us in the field of CALL are like this too.

This same sentiment is also reflected in the autobiography of Fei-Fei Li (2023), a Stanford-based AI research scientist who is credited with having been instrumental in the development of ImageNet, and who co-founded the Stanford Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence. In her memoir The Worlds I See, she describes her youth in Shanghai spent interested in both physics and literature, her family’s move from China to the US and the linguistic and cultural experiences she has as an immigrant, and her repeatedly reinforced position that humanist insights and principles are essential elements for informing technological problems. She relates an example of a skeptical grad student who doesn’t see the importance of debating ethical issues when his research is seemingly so far from practical application, and tells him that she understands the sentiment, but that she also lived through a period where the field didn’t think practical application was close, until all of a sudden it was, and the ethical and humanist implications of that research all of a sudden became relevant overnight.

References

Duranti, A. (2010). Husserl, intersubjectivity and anthropology. Anthropological Theory, 10(1-2), 16-35.

Dreyfus, H. L. (1992). What computers still can’t do : a critique of artificial reason. MIT Press.

Li F.-F. & OverDrive Inc. (2023). The worlds I see. Flatiron Books.

Han, B.-C. (2015). The Burnout Society. Stanford University Press. http://www.sup.org/books/title/?id=25725.

Masamune Shirow : Kodansha Ltd. : Bandai Visual Co. Ltd. : Manga Entertainment. (1995). Ghost in the Shell.

Moore, A., Gibbons, D., & Higgins, J. (1987). Watchmen. DC Comics.

Morton, T. (2013). Hyperobjects : philosophy and ecology after the end of the world. University of Minnesota Press.

Patwardhan A. (2023). Artificial Intelligence: First Do the Long Overdue Doable. Journal of Primary Care & Community Health, 14. https://doi.org/10.1177/21501319231179559

Rehman, F., Munawar, A., Iftikhar, A., Qasim, A., Hassan, J., Samiullah, F., Ali Gilani, M.B., & Qasim, N. (2020). Design and Development of AI-based Mirror Neurons Agent towards Emotion and Empathy. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications(IJACSA), 11(3).

Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures. (2008). Wall-E.

This is one of the most thought-provoking and well-written pieces on AI and education that I’ve read – thank you so much for your contribution, Johnathon!

Thanks so much for your kinds words Edie!