Professional Development in the COVID Era

By Amelia Ijiri, Adjunct Lecturer, Kyoto Sangyo University, and Betsy Lavolette, Associate Professor, Kyoto Sangyo University

DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.69732/WQUE5728

Introduction

As teachers worldwide retooled to move classes online, formal and informal teacher resources for professional development (PD) experienced unprecedented growth. This article is a brief introduction to three categories of PD: institutional, which includes faculty-organized informal groups within individual institutions; professional organizations, such as the International Association for Language Learning Technology (IALLT) and the Japan Association of Language Teachers (JALT), which pivoted to online conferences; and social media, such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and TikTok, which offer teacher tips and support. In this article, we write from our perspectives as English instructors working at a medium-sized university in Japan to introduce free resources for teachers to develop their own local communities of practice and suggestions for useful communities and resources available online.

You probably have a good understanding of what PD is, but we’d like to clarify that we are focusing on activities that help language faculty improve their teaching, rather than research, or other skills needed for their work. In some contexts, PD is also referred to as faculty development (FD) or teacher development (TD), but we will use PD in this article. Because we are in the COVID era, we focus on PD that takes place online. We also discuss communities of practice, which are “groups of people who share a concern or a passion for something they do and learn how to do it better as they interact regularly” (Wenger-Trayner & Wenger-Trayner, 2015, p. 1). Most of the PD-focused groups that we introduce can be seen as communities of practice.

According to Duguay and Vdovina (2019), effective, engaging, and sustained PD should be

- Research-based, content-driven, and relevant

- Meaningful and intellectually stimulating

- Engaging, interactive, and collaborative

- Well-organized and facilitated

- Positively framed, respectful, and inclusive

- Supportive of future learning and growth

(p. 2)

How do the different categories of PD measure up? We comment on each category below.

Institutional Professional Development

Institutional PD includes, for example, online or offline workshops/webinars on topics such as the learning management system or video conference system, and lists of resources (such as Betsy’s Online teaching resources). In this section, we focus on another type of institutional PD: communities of practice focused on teaching. While academic organizations and social networks may be the first places you check when you have unfulfilled PD needs, we believe that a PD group that is based at your own institution has the advantage of being specific to your context. That is, they have access to the same institution-provided tools, with the same options enabled or disabled by the institution. In addition, if instructors share information about the tools that the institution supports and choose to use them in their teaching, they can reduce the burden on students, who may otherwise be burdened with learning and using a large number of different apps.

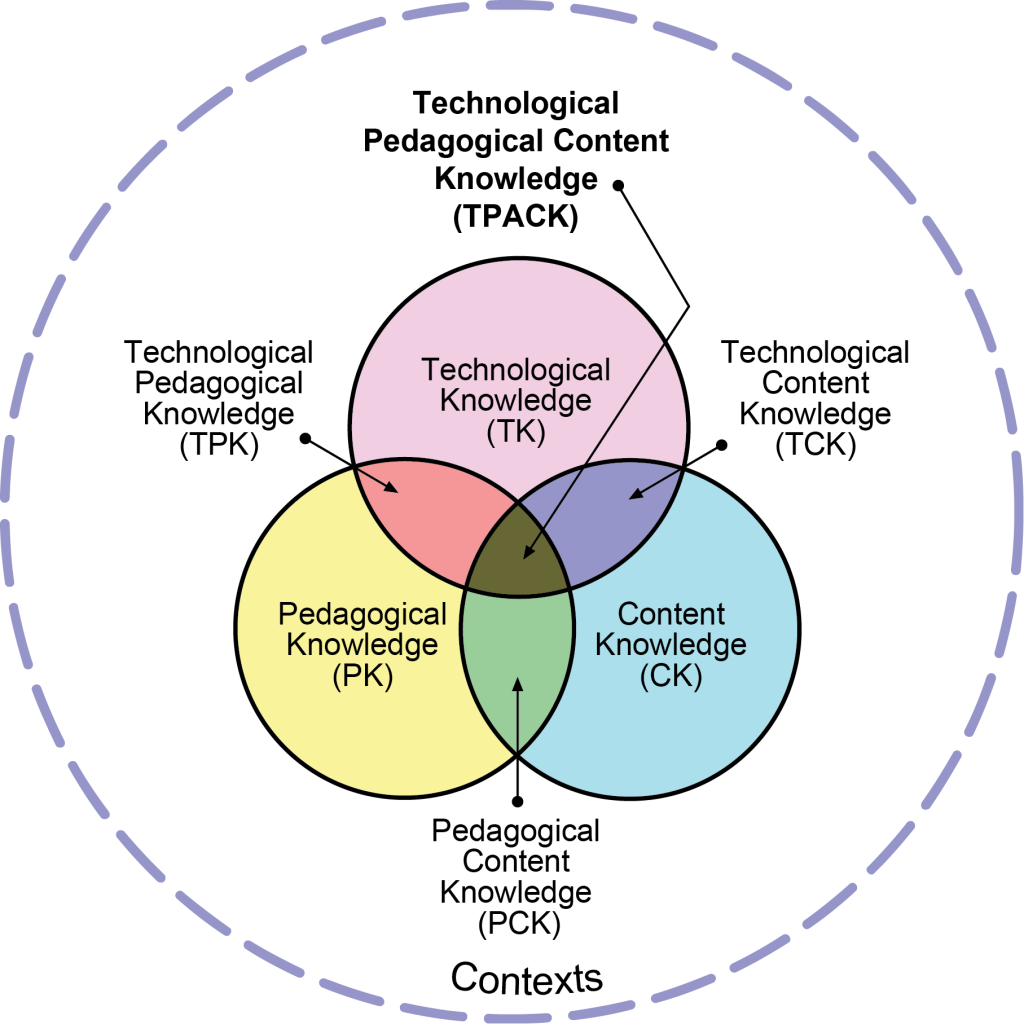

In fact, the TPACK model (Picture 1) emphasizes the importance of contexts as relevant to all types of knowledge that teachers need, including technical knowledge, pedagogical knowledge, and content knowledge, and their intersections. In the transition to emergency remote teaching, many instructors found that they particularly needed work in the technical knowledge area and its intersections (TPK, TCK, TPACK).

In our context in Japan, language centers (including self-access learning centers) generally do not provide PD for language teachers (Lavolette, 2019). Institutions do not necessarily have centers for teaching, educational technology centers, or other units that can flexible provide PD as needed. The PD that is offered (often unrelated to teaching) is usually only available to full-time professors and only in Japanese, which excludes part-time teachers (Skeates, Gough, Snyder, & Yanase, 2020) and those without sufficient Japanese language skills. Although Gacs, Goertler, and Spasova (2020) recommend collaborating with institutional educational technology experts when designing an online course, that is not an option for most teachers in Japan, even in non-emergency circumstances. Therefore, “instructors may need to rely on ad hoc or already established personal learning networks or professional organizations such as the Computer‐Assisted Language Instruction Consortium (CALICO) or the International Association for Language Learning Technology (IALLT)” (Gacs, Goertler, & Spasova 2020, p. 384). We address professional organizations like these below. In this section, we discuss institutional ad hoc PD networks.

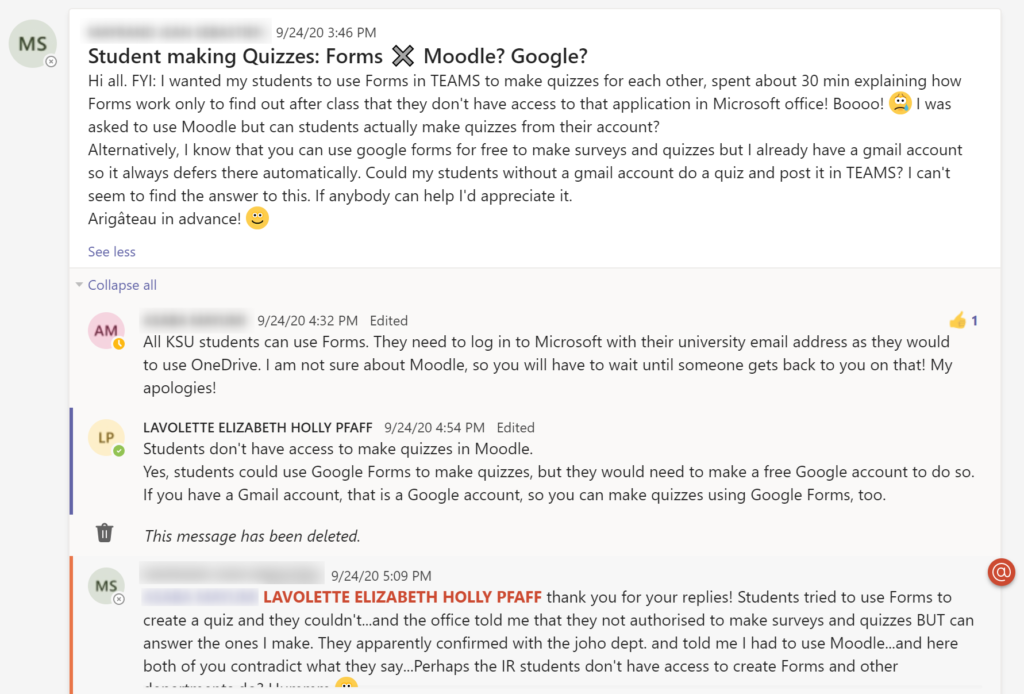

At our institution (Kyoto Sangyo University), Betsy’s tech office hours, a group on Microsoft Teams, has been a supportive community of practice that has helped teachers develop their technical knowledge, particularly knowledge related to the technology they have available at Kyoto Sangyo. In the language of the TPACK model, we have developed our TK,TCK, & TPK. For example, Picture 2 shows a question related to technical knowledge, but it would not have been possible to answer without knowledge of the university context.

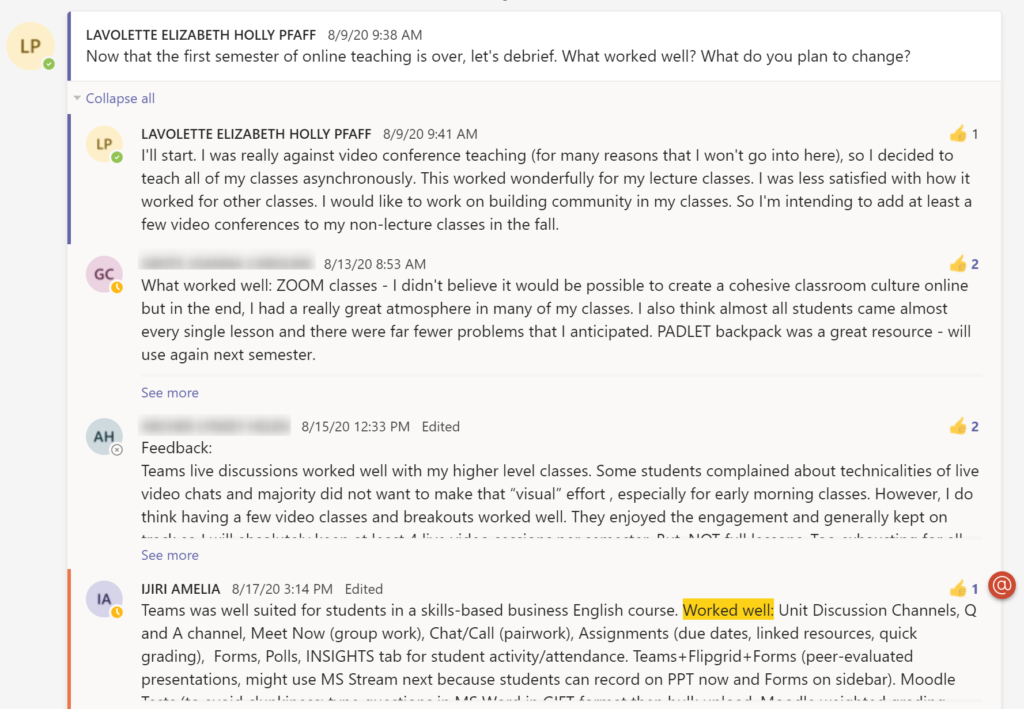

The Team has also been helpful for learning what worked well for other instructors and what went poorly. The question that Betsy posed to her colleagues after the end of the spring 2020 semester was: “Now that the first semester of online teaching is over, let’s debrief. What worked well? What do you plan to change?”

From their replies, Betsy learned a lot about what other teachers were trying and used some of their ideas in planning the fall semester. For example, Amelia said that she asked students to do group activities on their own, rather than trying to manage the groups. From this spark of an idea, Betsy decided to put students into teams for projects in her business English class, and it worked extremely well. In fact, with this change, the online class worked much better than the previous face-to-face format.

We used Microsoft Teams to form our community of practice. This paid tool was convenient because all faculty members, including part-time teachers, had access through the university. It allows for both text chat, as shown in Pictures 2 and 3, and video chat, which we used for synchronous workshops and forums. However, if your institution does not have a similar system, you can make a free account on a similar service such as Slack or Discord. All of these tools allow you to create a private social network, where you can create channels for text-based discussions focusing on topics of interest, host video and audio conferences or webinars, and send private messages to other participants.

Betsy is currently involved in a research project (with coresearcher Dennis Koyama) to understand the state of institutional PD in Japan and internationally. In the meantime, there are many recent examples of institutional PD at Japanese universities:

- Skeates, Gough, Snyder, and Yanase (2020) found that one part-time lecturer was providing technical assistance to other part-time teachers.

- Dennis Koyama (personal communication) managed a FAQ about Moodle at Sophia University.

- Isaacson (2020) conducted weekly online workshops over Google Meet.

- Uchida (2020) set up Google Classroom and held sessions for teachers, such as Zoom practice, Google Classroom practice, sharing resources, tutorial videos, and documents.

Institutional communities of practice have the potential to fulfill all of Duguay and Vdovina’s (2019) criteria for effective, engaging, and sustained PD. A particular strength of this type of PD is its relevance to participants, who are normally the ones bringing up the ideas for discussion. However, these communities may not be supportive of future learning and growth if teachers no longer see technology as relevant to their teaching (e.g., when they return to the face-to-face classroom). These communities may be considered inclusive if they specifically include part-time teachers and teachers who cannot benefit from other institutional PD. On the other hand, they may be considered exclusive because they are only open to teachers at a given institution. This type of exclusivity is a problem that can be overcome by the other types of PD: professional organizations and social media.

Professional Organizations

Many faculty consider conferences instrumental to connect and learn from each other. These micro time-bound communities of practice sometimes lack the regular connection that online communities offer (MacGillivray, 2017). However, this year, geographic restrictions lifted because many organizations offered online conferences via Zoom. The conferences organized speakers and “host rooms” in a variety of ways. Here are some of the conferences that we are personally familiar with:

- Kyoto JALT (Kyoto chapter of Japan Association for Language Teaching): Live Zoom sessions were offered frequently throughout 2020 and 2021.

- CercleS (Europe): The conference was held both face-to-face in Brno, Czech Republic, and online, in synchronous sessions on Zoom (September 2020).

- Japan Association for Self-Access Learning (JASAL): The annual conference was fully online, with videos submitted in advance and played during synchronous Zoom sessions. Live Q&A sessions were held after the videos (December 2020). An additional networking session was held using Spatial Chat.

- Center for Education of Global Communication (CEGLOC) (University of Tsukuba, Japan): The conference was held fully online on Zoom (December 2020).

- The Midwest Association for Language Learning Technology (MWALLT) changed the format of their conference to “lightning talks.” Presenters introduced a brief teaching idea, a tech walk-though, or a lesson plan in 5-10 minutes. Using this format, the conference offered 18 “lightning talks”: six sessions in three host “rooms,” four more in-depth, 60 minute “mini- workshops,” and a conference debriefing, all by noon on February 13th, 2021.

- Arbeitskreis der Sprachenzentren (AKS, Germany): The conference was held fully online as synchronous sessions on Zoom (March 2021).

- Computer Assisted Language Instruction Consortium (CALICO): This conference gives presenters the option to present synchronously or asynchronously (video submitted in advance) (June 2021).

- IALLT: The organizers plan to hold some synchronous sessions on Zoom (e.g., keynote, poster sessions) and make other sessions available in advance as videos, with synchronous Q&A sessions held in related groupings (June 2021).

Returning to Duguay and Vdovina’s (2019) criteria for effective, engaging, and sustained PD, professional organizations generally provide PD that is research-based, content-driven, and relevant to their members. These organizations usually have overseeing boards that endeavor to make PD respectful and inclusive.

Online Professional Development

Certainly, in the years preceding the pandemic, professional learning networks (PLNS) and online learning communities of practice (CoPs) were established places for faculty members to engage in professional learning (Luo, 2020). These communities served as modern-day water cooler chats offering all types of social support including emotional, appraisal, informational, and instrumental (Kelly, 2016). Social media as a CoP has the benefit of being unplanned, unstructured, and driven by the learner lending itself setting itself in the concept of informal learning theory (Luo, 2020): learning outside formal structures, like a classroom, with no clear goals or set objectives: With teachers around the world adapting their classes for online instruction, a spirit of collaboration and sharing developed in the form of Facebook groups and teachers connecting with each other on Twitter, Instagram, and TikTok. YouTube made recorded lessons available for students and also served as on-demand professional development as teachers uploaded screen-casts.

In the case of Japan, Online Teaching Japan (OTJ) was created on March 29th, 2020, for “teachers to share ideas, technology and best practices concerning teaching online.” It is a “closed” Facebook group, meaning that you must request membership and only members can see who is in the group and what they post. This online message board that initially served as an exchange board for teachers eventually grew into a week-long online conference with thirty-one presenters held in August 2020 and a Friday night “Zoombar,” which is an informal networking online happy hour that includes webinars with invited guests.

When K-12 schools started going fully online, Teaching During COVID-19 was started as a closed Facebook group with a few thousand teachers. Within a year, this group grew to 136,000 members (as of March 9th, 2021). This group has a wealth of information about what is happening in different school districts in the USA, teaching ideas, and plenty of humor. This humor sometimes takes the form of “memegates,” where you have to add a teaching meme in the comments to jokingly “pass through.” Some discussion about special education and social-emotional self-care fit nicely in this group’s supportive, helpful, and caring dynamics.

Another very useful group is Teacher Tech Alice Keeler (closed, 38K members as of March 9th, 2021). Alice Keeler and Melody McAllister moderator group posts about Google Classroom, knowledge sharing, free PD, Microsoft, and hybrid teaching. They hold weekly live sessions on Steamyard, a live streaming platform that allows the presenter to share Facebook, YouTube, and LinkedIn audience comments as pop-ups on the screen. As a professional, on-demand, and in-time resource for teachers, this group has a lot to offer among other similar Facebook groups that sprang up around the same time.

Twitter, a microblogging tool, is a great source of inspiration for connecting to other teachers and finding out what is going on in different classrooms. Twitter’s use of hashtags (keywords) such as #langchat, #academictwitter, and #edutwitter allow academics to find each other amid all the noise (MacGillivray, 2017). Additional hashtags like #HigherEd, #elearn, #PhDchat, #research, and #edtech enable the initial step of finding educators with shared interests in the development of communities of practice (MacGillivray, 2017). Twitter also offers scheduled online conversations with predetermined topics, for example, #HigherEdchat (MacGillivray, 2017).

Instagram, a platform popular for its visually appealing interface, is a good fit for delivering short tech tips. Many techy teachers began or expanding their Instagrams during this period including A Primary Kind of Life (@aprimarykindoflife) who posts include rainbow-filled ideas to add color to the somewhat drab palette of computer class files. This certified Google trainer offers how-to resources on everything from changing your “ugly blue Mac folders into something cuter” to scheduling parent-teacher conferences virtually by using @calendyhq. Calendyhq is a scheduling app that integrates Zoom, Google Meet, and Teams, solving a common problem for teachers trying to hold online parent-teacher conferences. This type of example of teachers helping teachers with quick, useful, free ideas that can be implemented immediately to solve shared problems is, perhaps, what social media sites, such as Instagram, do best.

TikTok

Dr. Simon Howard, an assistant professor of psychology at Marquette University, taught his Gen-Z students using an innovative digital method by asking his students to create TikToks that demonstrated theories and concepts (Mileusnic, 2021). Teachers also picked up on this engaging, educational, and practical online format for PD tips. TikTok videos can have a duration from fifteen seconds to one minute. This duration is enough to see teaching hacks such as turning a PDF into a Word Doc (@techcoachtips, 2021), using an iPad as a whiteboard (@qbinmamiteachers2nd, 2021), and using your bitmoji as a custom cursor (@roxyteachers, 2021). Some teachers on TikTok focus on a specific app, such as @mrswhiteinmiddleschool, who posts Peardeck tutorials. Popular hashtags for professional development are #tiktokteachers, #teachersoftiktok, and #teachertechtips.

YouTube

Parents and teachers are sometimes taken aback to hear kindergarteners say that they want to be YouTubers when they grow up, but school closures and online learning made YouTube not only a way to deliver lessons, but also expanded its prominent place as a DIY data base for teacher how-to video to a seemingly endless resource for professional development. Teachers looking for new technologies searched YouTube, often finding teacher-made materials, for example, “Drive App to Create a Google Doc from printed materials” by Kimberly Jacquay, or “Sort Responses from Google Forms to Google Sheets Tabs” by Joli Boucher.

In terms of Duguay and Vdovina’s (2019) criteria for PD, online communities offer teachers a variety of benefits, such as emotional support and increased confidence, motivation, and self-esteem (Lantz-Andersson, 2018), thus providing a meaningful and intellectually stimulating environment. The accessibility of online platforms supports future knowledge building and growth. Informally-developed online teacher communities can be engaging, interactive, and collaborative spaces within time-relevant topics and sharing. However, large ad hoc networks also run the risk of becoming irrelevant, and the information shared is not always factual.

Conclusion

Technology enables knowledge-building communities to scale up to geographically distributed communities of practice (Hoadley & Kilner, 2005), and online communities appear to be an important mechanism for the generation and dissemination of PD knowledge to faculty and staff. Online communities which provide a culture of trust where members feel safe to challenge each other’s assumptions, offer possible suggestions and flesh out unconventional ideas, have potential to transform from document repositories or simple chat rooms to knowledge-building communities of practice (Hoadley & Kilner, 2005).

Teachers are developing their own communities of practices at their institutions, participating in online conferences with professional organizations, and contributing to and sharing with online communities. This has some significant advantages over purely face-to-face PD, particularly for professionals that previously could not access PD due to distance, disability, caregiving and other family obligations, etc. In addition, online PD is more accessible to part-time faculty who are not always on campus or financially able to attend location-based PD.

One way to keep this level of inclusion is with a hybrid format for conferences and other PD events that offers more options for participation. If organizations find this technically impractical, they could continue to offer a completely online option, much in the same way people are choosing online options, for example, e-journals instead of receiving paper copies by mail even though the look and feel might be different, it could be the new normal.

The pivot to online teaching during COVID forced institutions to think and act digitally, and thus, make PD more inclusive. On the strength of this spirit of collaboration and inclusivity, this PD that has so rapidly developed via the Internet deserves a permanent place in education.

References

Brereton, P. (2020). Emergency remote training: Guiding and supporting teachers in preparation for emergency remote teaching. Language Research Bulletin (International Christian University, Tokyo), 35, 1–13.

Duguay, A. L., & Vdovina, T. (2019). Effective, engaging, and sustained professional development for educators of linguistically and culturally diverse students. Washington, DC: Center for Applied Linguistics. https://www.cal.org/resource-center/publications-products/effectivepd

Gacs, A., Goertler, S., & Spasova, S. (2020). Planned online language education versus crisis-prompted online language teaching: Lessons for the future. Foreign Language Annals, 53(2), 380–392. https://doi.org/10.1111/flan.12460

Hoadley, C. M., & Kilner, P. G. (2005). Using technology to transform communities of practice into knowledge-building communities. ACM SIGGROUP Bulletin, 25(1), 31–40. https://doi.org/10.1145/1067699.1067705

Lavolette, E. (2019). A very brief introduction to US language centers. In L. Xethakis & C. Taylor (Eds.), JASAL 2018 x SUTLF 5: Selected papers from the Sojo University Teaching and Learning Forum 2018: Making connections (pp. 4–25). Kumamoto, Japan: NanKyu JALT. https://www.nankyujalt.org/publications#h.p_twJDnQsJDWmj

Luo, T., Freeman, C., & Stefaniak, J. (2020). “Like, comment, and share”—professional development through social media in higher education: A systematic review. Education Tech Research Dev 68, 1659–1683 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-020-09790-5

Kelly, N., & Antonio, A. (2016). Teacher peer support in social network sites. Teaching and Teacher Education, 56, 138–149.

MacGillivray, A. E. (2017). Social learning in higher education: A clash of cultures?. In J. McDonald & A. Cater-Steel (Eds.), Communities of Practice. 27-45. Singapore: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-2879-3_2

Mileusnic, N. (2021, February 2). Marquette Professor uses TikTok in the classroom. Marquette Wire. https://marquettewire.org/4045900/news/professor-uses-tiktok-to-enhance-learning-in-the-classroom/

Skeates, C., Gough, W. M., Snyder, B., & Yanase, C. (2020). Experiences researching English part time university lecturer voices during ERT. https://sites.google.com/view/teacherjourneys2020/home

Uchida, A. V. (2020). Reflections from my ERT journey. https://sites.google.com/view/teacherjourneys2020

Wenger-Trayner, E., & Wenger-Trayner, B. (2015). Communities of practice: A brief introduction. https://wenger-trayner.com/introduction-to-communities-of-practice/