Online Translators in Language Classes: Pedagogical and Practical Considerations

By Florencia Henshaw, Ph.D., Director of Advanced Spanish, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign

DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.69732/SFBF9402

Nothing sparks more debate among language educators than the mere mention of Google Translate, other than perhaps the role of explicit grammar instruction. We might not be on the same page about whether online translators (OTs) are a useful tool or unauthorized assistance, but we all agree that they are here to stay and continuously improving. The efficiency appeal of a tool like Google Translate is hard for students to resist and for instructors to deny: using OTs is easier and faster than unassisted language production (and for some languages, just as accurate or more!).

In classes with a face-to-face component, or “mask-to-mask” in the post-pandemic world, preventing the use of unauthorized resources is somewhat easier: no take-home writing assignments. However, in fully online courses, that is not an option. As the designer and supervisor of several online Spanish courses, ranging from novice to advanced, I have given this issue some thought. In this article, I share my insights and propose some pedagogical and practical considerations for dealing with OTs in the language classroom.

Perceptions and policies

Students view OTs as one more tool, akin to dictionaries and spell check. Indeed, studies have found that the most popular use of OTs reported by undergraduate students is to look up words they want to understand or convey (Clifford, Merschel, & Reisinger, 2013; Faber & Turrero Garcia, 2020). Ironically, that’s when the accuracy of machine translation goes down, since the algorithm thrives on context. Students also rely on OTs to confirm or revise what they wrote, which seems odd from the instructor’s point of view, since online translators are not exactly known for their accuracy.

Understanding how instructors’ and students’ perceptions differ is crucial to draft course policies that make sense to all stakeholders. If students can look up a word in Linguee, why can’t they look up the same word in Google Translate? If spell check or similar “grammar checker” sites are allowed, why can’t they use an OT for editing purposes? It all boils down to the extent of the assistance that each tool affords. Unlike Linguee, Wordreference, or spell check, OTs could potentially tell students, for better or worse, exactly what they should say, without involving any meaningful decision-making, other than whether or not to trust its output. And in that sense, it would be comparable to asking someone else to complete the assignment for them. Sites like Linguee, on the other hand, offer several choices and leave it up to the students to make the final decision, thus reflecting their abilities more closely. As evident as this may seem to us, it may not be to our students.

Practices and pitfalls

A clear policy with respect to authorized and unauthorized resources is absolutely necessary, but we know it is not enough to dissuade students from resorting to OTs. Language educators often ask each other for ideas and advice to grapple with OT use, and responses are as varied as there are teachers. I will briefly explain and critically reflect on five of the most common approaches, and I will later propose a sixth alternative that tackles the inevitable omnipresence of OTs from both pedagogical and practical angles.

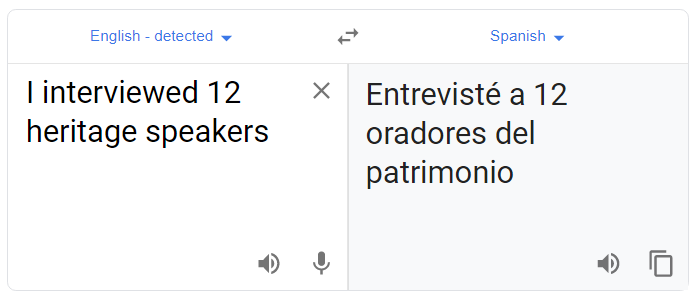

Approach #1: “Can’t trust this”

This is probably the very first tactic ever used against OTs: telling students that machine translation is highly inaccurate and results in ridiculous literal translations. This argument used to be quite convincing, but online translators have improved vastly in the last few years, at least for some languages. OTs are still struggling with songs and some discipline-specific jargon without enough context (e.g. see Google Translate’s attempt at the term “heritage speakers” below), and their output might never be flawless, but it can certainly handle the type of simple sentences on familiar topics that novice and intermediate learners tend to write about. I would venture that Google Translate is at least “Advanced-Low”(ACTFL, 2012) in Spanish, though its proficiency certainly varies by language.

The most fascinating pitfall of this approach is that students seem to be well aware of the fact that OTs are inaccurate, and yet they continue to find them useful. According to Clifford et al. (2013), 91% of students surveyed said they detected errors, and yet 94% considered OTs to be always or sometimes helpful. Why? Because using Google Translate, as opposed to only an online dictionary, seems to help them write more accurate essays (O’Neill, 2016, 2019). It is clear that we need a different approach.

Approach #2: “One word only”

Some instructors allow the use of OTs to look up a single word or idiomatic phrase, presumably equating OTs to dictionaries. The issue with this approach is that the more isolated the input, the less accurate the OT is. For instance, “paper jam” is inaccurately translated by itself (resulting in something along the lines of “marmalade of paper”), but it is perfectly accurate when one adds the words “in printer.” Therefore, the one-word approach presents more cons than pros, given that it almost certainly leads students to inaccurate results.

In a similar vein, the “ten items or less” approach entails setting a maximum number of words a student can look up, and asking them to disclose which words they obtained from outside sources. Unfortunately, the issues that we know result from word-for-word translation prevail, and some instructors anecdotally report a “slippery slope” effect, where the number of words students end up looking up is much greater than what they are disclosing. Additionally, could disclosing the source of the word make students feel less responsible for any inaccuracies?

Approach #3: “Zero tolerance”

It is common for educators to dissuade OT use by warning students that doing so results in a zero on the assignment, on the basis of academic dishonesty. Although this sounds effective in principle, there are some issues that arise in practice because institutions tend to have a process in place for handling academic dishonesty cases, which helps to ensure that students are treated fairly. And when a case involves alleged use of an OT, things can get tricky. First, it is almost impossible to determine unequivocally the source of the unauthorized help. If we were accusing students of having copied someone else’s words without proper citation, it would not be enough to say “this sounds like something someone else wrote; I don’t know who, but I am giving you a zero because you must have copied it from somewhere.”

Another issue with this approach is that research has shown that instructors are not always accurate at determining which writing sample was produced with the help of a translator. In other words, it could be possible to falsely accuse a student of cheating. In O’Neill’s (2013) study, the error rate of false positives (i.e., suspecting the assistance of a translator when that was not the case) was as high as 26.5%. Of course, it is quite possible that if participants in O’Neill’s (2013) study had been rating their own students’ samples, the accuracy rate might have been much higher. Nonetheless, the takeaway is that academic dishonesty allegations should not be taken lightly, and all educators should familiarize themselves with their own institutional policies and procedures before jumping on the “zero tolerance” bandwagon.

Approach #4: “Where did you learn that?”

This approach entails strict limits: students are required to use only words or structures they have learned within the confines of the course. Odds are that the OT will produce language that has not been taught, which is seen not only as evidence of cheating, but also presumably harmful to the learning process because it might confuse students. On a practical level, the main challenge with this approach is that it is not clear how the instructor can keep track of all of the words and structures students have learned over time (i.e., several courses with possibly other instructors).

More importantly, this approach raises a number of serious concerns from a pedagogical standpoint. First, don’t we want students to express what they want to communicate, and to expand their language abilities, as opposed to limiting them to recombine learned material or forcing them to say things in a particular way? Approaching a communicative act in such a restrictive manner sends a clear signal to students that the focus of the assignment is not what they say (i.e., meaningful content), but rather how they say it (i.e., grammar).

Second, we are doing our students a disservice by sheltering them from language that exists outside of the classroom walls. Our goal as language educators should not be limited to helping students do well on exams that test their knowledge of specific material. We should be motivating them to become lifelong learners. Don’t we want students to seek the target language outside of class, so they can continue developing their language skills? I personally encourage students to use some of these resources for Spanish on their own, participate in conversation groups, and embrace any chance they get to learn from other speakers of the target language.

Last but not least, this approach seems to be based on the problematic assumption that the only acceptable dialects are those that are used by the instructor and/or the textbook. Shouldn’t we be fomenting an appreciation for linguistic diversity? And by the way, OTs are also unhelpful in embracing dialectal differences, since their output cannot be tailored by dialect, whereas spell check in Microsoft Word, for instance, acknowledges the existence of language varieties.

Approach #5: “If you can’t beat them, join them”

Rather than banning OTs, proponents of this approach maintain that their output can be used to heighten students’ awareness of various aspects of language, mainly grammatical forms, through translation and editing exercises (Correa, 2014; Enkin & Mejías-Bikandi, 2016; Faber & Turrero Garcia, 2020). The first potential pitfall of this approach is that it tends to treat language as the object of study. Faber and Turrero Garcia (2020), for instance, see OTs as a tool “to test students’ understanding of the fine-grained aspectual distinctions studied in this part of the course” (Translator activity section), which implies a certain degree of emphasis on the importance of metalinguistic knowledge. The question that arises is: if our pedagogical goals don’t include learning about the language, what do OTs have to offer?

Another drawback of dissecting inaccuracies, especially when they involve the complex issues that OTs struggle with (e.g., long-distance agreement, mood selection in subordinate clauses, etc.), is that it might contribute to perpetuating the notion that the teacher expects perfection. In reality, according to ACTFL Proficiency Guidelines (2012), the writing of learners at the Intermediate-High level (i.e., after several years of study) may have “numerous and perhaps significant errors,” that may at times result in possible “gaps in comprehension.” If we are subjecting the output of OTs to ruthless scrutiny, when it is actually more accurate than what novice and intermediate learners can produce unassisted, we might be inadvertently sending the wrong message about our expectations.

Other challenges with this approach, which Faber and Turrero Garcia (2020) acknowledge, are that (1) OTs may have already or might eventually overcome those grammatical struggles, resulting in a never-ending quest for faulty output, and (2) some learners are wrongfully concluding that you can’t trust the grammatical accuracy of OTs, but they are still helpful for single words, when in reality, isolated words are the Achilles heel of OTs.

Also stemming from the premise that banning OTs is futile, the “enjoy responsibly” approach advocates for training students on how to use OTs so they can get the most out of them. Indeed, O’Neill (2019) found that writing tasks produced by students who received training on using Google Translate were rated higher than those submitted by all other groups. However, it is unclear to what extent we can consider those submissions to be a reflection of the students’ abilities in the target language, as opposed to their abilities in using Google Translate. Moreover, does this practice contribute to language development? According to the same study, the answer appears to be no: students who received training on using Google Translate performed worse than the other groups when they had to write a composition on their own, presumably because they had become overly reliant on Google’s help (O’Neill, 2019). More research is needed to further explore the link between OT use and language development. For now, the role of OTs as pedagogical tools remains unclear.

A two-pronged proposal

The challenges and pitfalls with the myriad of approaches educators have come up with underscores the complexity of this issue. Even though upholding academic integrity is of utmost importance, trying to police and prosecute OT users in light of the challenges of the “zero tolerance” approach seems to be doing more harm to our rapport with our students than good in terms of curbing their reliance on OTs. Furthermore, while it is true that bilingual professionals use online tools out in the real world, and we should equip students with the knowledge necessary to make good choices on their own, how do we ensure that we are not creating the perfect loophole for academic dishonesty?

What I propose instead is to direct our efforts toward reducing students’ motivation to use OTs, by implementing both pedagogical and practical changes to our courses. My goal is essentially to create what Ducar and Schocket (2018) call a “Google-irrelevant” classroom, but without so much emphasis on translation activities and dissection of OTs’ strengths and weaknesses, given some of the concerns I delineated above.

Pedagogical considerations

If our goal is to help students develop communicative ability in the target language at a certain proficiency level, every single component of the course, from the materials to the grading rubrics, should reflect that. Our expectations should be in line with the proficiency level of the students, and our instructional practices should be in line with what we know about second language acquisition. Here are some questions to ask ourselves:

- Are students at the targeted proficiency level able to do what we’re asking them to do? If you ask an Intermediate-Low learner to write a 200-word paragraph about something memorable that happened during a trip (with good control of past tense), you are bound to see an increase in OT use. And the students are bound to mistakenly conclude that they are just not good at learning languages.

- Are students being evaluated on what they can do with the language at the targeted level? If our rubrics insist on a level of grammatical accuracy that is unrealistically high for their level, we are giving students reasons to want to use OTs because, despite some errors, their output is still more accurate than what many of our students can produce on their own, at least for some languages like Spanish.

- Have we adequately prepared students to do the assignment in a relatively unassisted way? Doing computer-graded mechanical practice (e.g., matching vocab words with pictures, or filling in blanks with the correct verbs) does not prepare students to write a short paragraph about their family or favorite vacation spot.

- Are we moving too quickly from input to output? Is the proportion of interpretive communication, relative to presentational and interpersonal communication, adequate for the level of the students?

- Are we being realistic with respect to what we are aiming for? If students entering the course are Intermediate-Mid, we cannot expect them to be Advanced-High after a few weeks.

Practical considerations

It is important to recognize that even if we have done everything right pedagogically, some students will resort to OTs to complete the simplest of assignments, merely because of convenience. If they can save 2.5 seconds by asking Google how to say “My name is…,” as opposed to trying to express that on their own, they will. Therefore, we also need to make course modifications on a more practical level.

First, as you plan your online course, classify your assignments into one of these three categories:

- Green: students are likely to succumb to the temptation of OTs to complete them. Some examples would be written forum posts or open-ended responses; reading comprehension based on texts that can be translated automatically with the Google Translate browser extension.

- Yellow: students could seek help from OTs to complete them, but the assignment format makes it less convenient. For example, short video presentations that are rehearsed but unscripted (i.e., they can plan what to say, but they cannot read), or comprehension-based activities where the text is presented in the form of a screencast video (e.g., example of a “video reading”), which also helps students hear the words they are reading.

- Red: OT use would be extremely impractical or impossible. Examples in this category include remotely proctored written assessments, synchronous sessions with the instructor or other speakers of the target language through platforms like LinguaMeeting or TalkAbroad (I’ve reviewed several of them here: “Video chatting with Native Speakers: Why, What, and How”), and unrehearsed asynchronous video responses on Extempore, where you can set up the recording to start automatically, as soon as students see or hear the prompt.

Then, the weight of course components is distributed in a way that the highest percentages (15%+) go to “red” assignments, followed by “yellow,” and the lowest being “green” assignments. And I mean truly low-stakes: for example, bi-weekly forum posts might only count for 5% of the course grade. Needless to say, all of the assignments, regardless of their weight, should be carefully crafted in light of the pedagogical considerations outlined above.

Absolutely paramount is to help learners understand that even though low-stakes assignments might not be worth much in terms of their final grade, they are still worth their time because they are meant to help them prepare for higher-stakes (“red”) assignments, and that connection should be explicitly made in the syllabus. If they choose to rely extensively on an OT for the low-stakes assignments, they will not gain much in terms of points, and they will actually lose a lot in terms of learning. They will miss out not only on developing communicative ability, but also on the cognitive benefits and personal growth that learning a language entails, from improving their ability to multi-task and process information to building humility, empathy and confidence, just to name a few. I suppose this approach could be called “it’s their loss.”

Caveats and calls to action

This approach is not without its limitations. For instance, the practical solutions outlined above do not address the unique situation of fully online composition courses, where high-stakes writing assignments (i.e., 1,500-word essays) cannot be eliminated or proctored. All language educators would probably welcome a tool that can effectively monitor at-home writing assignments, without the privacy concerns surrounding online proctoring services.

Another caveat about the approach I propose is that it involves undoing the hardwired perception that only near-perfect work deserves full credit, and that takes time and trust. Do students believe us when we say we are not expecting perfection? And do we really mean it, or could there be some mixed messages when it comes to performance expectations?

We would also benefit from more research on potential benefits and drawbacks of using OTs and online dictionaries for language development, along the lines of O’Neill (2019), to better guide our policies and practices. Likewise, we need action research to confirm whether using OTs with advanced students, as suggested by Correa (2014) and Enkin and Mejías-Bikandi (2016), leads to an improvement in their self-editing skills: does raising students’ metalinguistic awareness through OT editing activities help them become better unassisted self-editors?

On a broader level, it would be helpful to have a more uniform view, across institutions, on whether using OTs constitutes a form of plagiarism or cheating. The lack of consensus among educators, reflected by the seemingly contradictory policies students encounter from course to course, have left OTs in academic integrity limbo.

More research, conversations, and reconsiderations are warranted. Even if my proposal is not a good fit for your courses, I hope to have provided some food for thought. No, Google, not literally.

References

ACTFL. (2012). ACTFL Proficiency Guidelines 2012 [Electronic version]. Retrieved May 27, 2020, from https://www.actfl.org/publications/guidelines-and-manuals/actfl-proficiency-guidelines-2012

Clifford, J., Merschel, L., & Reisinger, D. (2013). Meeting the challenges of machine translation. The Language Educator, 8, 44–47.

Correa, M. (2014). Leaving the “peer” out of peer-editing: Online translators as a pedagogical tool in the Spanish as a second language classroom. Latin American Journal of Content & Language Integrated Learning, 7(1), 1-20.

Ducar C. & Schocket D.H. (2018) Machine translation and the L2 classroom: Pedagogical solutions for making peace with Google Translate. Foreign Language Annals. 51: 779–795.

Enkin, E. & Mejias-Bikandi, E. (2016). Using online translators in the Second Language Classroom: Ideas for Advanced-Level Spanish. LACLIL, 9(1). 138-158.

Faber, A. & Turrero Garcia, M. (2020). Online Translators as a Pedagogical Tool. FLTMAG. Retrieved from https://fltmag.com/online-translators-as-a-pedagogical-tool/

O’Neill, E. (2013). Online translator usage in foreign language writing. Dimension: 74-88.

O’Neill, E. (2016). Measuring the impact of online translation on fl writing scores. IALLT Journal of Language Learning Technologies, 46(2), 1-39.

O’Neill, E. (2019). Training students to use online translators and dictionaries: The impact on second language writing scores. International Journal of Research Studies in Language Learning. 8 (2): 47-65.

Nice Article. Thanks for sharing one of the great content, really liked it.

Thank you so much!

Well Explained. Thank you for sharing such a wonderful article. Really like this post.

Thank you for your kind words! I’m so glad you liked it.

Hello again!

I was wondering if you made any progress on the policy you mentioned under “Practices and Pitfalls”. You were saying that “a clear policy with respect to authorized and unauthorized resources is absolutely necessary…”.

This is what I have for our upper-level composition course. Any course policies have to be in line with the university’s policies, so we cannot say, for instance, that they will receive a 0 (we need to follow the procedure established in the Student Code):

What kind of “outside help” is OK?

While we are not expecting perfection, it is important that the work you turn in be as “polished” as possible. In this course, you are allowed to use only the following resources as outside help with matters of language (accents, grammar, vocab):

• http://www.wordreference.com/

• https://www.linguee.com/

• Microsoft Word Spell Check

• Your instructor

Using any other type of assistance (from any other sites or people) is considered unauthorized help in this course. Alleged academic integrity violations will be handled following the process outlined in the Student Code: http://studentcode.illinois.edu/article1/part4/1-403/

Hi, Florencia.

I am setting up a Spanish grammar review course for use with high school and college students. Would I be able to utilize what you have provided as a general example of ways to use translating tools for assistance in class?

I’ve just come out of a meeting where we talked about this very topic : the dos and donts of online translation. We want to create a similar policy.

I enjoyed your article, and although I have been teaching long time, it has forced me to rethink some things about my courses. I am also intrigued by translators, and I like your suggestions you offer.

Thank you, Julia! I really appreciate your comment and willingness to reflect.

Thank you for this thought-provoking article, Florencia.

I pasted the link to an article I wrote on the same topic and I’m always looking for a group of educators interested in OT. If you’d like to meet as a group to discuss, email me at fstalder@aisb.hu. Also on Tweeter @mrstalder.

Students need to understand that practice makes progress, not perfect. I must say I agree with Nicholas. And I train my students to use Google Translate.

Arsena’s integration idea is the solution. What would it look like in practice ?

The last two words you said are the sticking point to me: in practice.

I have yet to see a way to integrate or incorporate them in a way that doesn’t create a loophole for academic integrity, or at the very least, mixed messages (a.k.a., grounds for disputes, at least in higher ed here in the US).

In advanced courses, where learners are there because they want to acquire and communicate in the target language, sure, I can see some use for them. In lower-level courses that students take sometimes reluctantly, and thus want to find the most convenient way of completing assignments, I have my doubts.

And my main concern is: how does using translators foster acquisition? How does it help my students develop communicative ability in the target language? I hear a lot about “bilingual professionals use tools” — yes, but how did they/we become bilingual professionals? We cannot compare novice learners taking courses for a requirement with bilingual professionals. I don’t think both populations use these tools the same way or with the same intent.

As you can tell, I like talking about this topic a lot! I’ll follow you on Twitter, and maybe we can keep the conversation going there.

I am struggling with this issue mid-way through a beginner course this fall. I took the chance to address it with students individually and as a class when a swath of assignments came in with translated material. The assignment was partially too difficult in terms of moving from input to output, however, half the class nailed it. We’ll leave extreme variation in level/ability for another post perhaps. I am adjusting some of my assessments to include more comprehension based questions because of this. After I addressed the whole class, I worked on helping them use ‘better’ resources and reinforcing the fact that making mistakes is natural and needed. I did go to a ‘zero tolerance’ approach after that (a day ago!).

I’d like to see more research on the student need to be ‘right’ and how their educational experiences that have reinforced that behavior are driving use of OTs. I am guilty of a couple of the pitfalls listed in this article and am adjusting an exam in another tab right now because of you! I have left vocabulary quizzes behind in exchange for story reading and studying (and using) vocabulary from those stories. I no longer give half points or quarter points for spelling or capitalization errors. I reinforce every day that the students will make errors and I expect and embrace that. I have read about teachers writing assignments (and even questions) in tiers – to get an A, do this, to get a B do that, which presents its own challenges but could be interesting. I still have a big question mark over my head on this issue but I’m open to evolving my approach as I go. My biggest question is still around assessing language progress that should/inevitably will have tons of errors and encouraging the students to make those errors.

Thanks for sharing your experiences, Margaret! The fact that you are so open to re-consider things and evolve is commendable. Keep up the good work! It’s not easy by any means, and it requires numerous adjustments along the way.

Having conversations with our learners about the benefits, limitations and effective use of machine translation has become an important part of our role as WL educators. And this article has been the primary resource I recommend to colleagues, methods students and friends seeking guidance. I thank Dr. Henshaw for providing us such a detailed overview.

Thank you for your kind words, Douglass! I am glad it has been helpful for initiating important conversations (even if sometimes those conversations are just with ourselves). That’s precisely what I was hoping this article would do.

This is so helpful. Every year I say I’m going to may a poster for my room that listss appropriate and inappropriate use of translators. You totally have me motivated.

Thank you, Le-Anne! I am very flattered by your kind words.

As a teacher i am very intrigued about lanuage professors defending their turf .i am sure as ot gets better the poking fun at the results will pale .every teacher must ask why are learning this for what purpose .Language is communicating and in time ai will improve beyond recognition.

Is it to communicate or is it an academic exercise to gain points for academic advancement. Or worse to support an out of date concept that teachers protect their livelihood by banning assistance.

Today we rely on computer assistance on driving a car who does not . Should i ban you from the road because you cheated in using computer technology to drive home safely

As a teacher i must ask the question what am i teaching .As teachers is your work always perfect.

Think about it.

I agree that AI will only continue to improve. And even if it is 100% perfect, I do think what we do matters. If you believe that all we do as language educators is helping students be walking translators, then I would invite you to reconsider that. Online translators (even if perfect), cannot replace any of “the cognitive benefits and personal growth that learning a language entails, from improving their ability to multi-task and process information to building humility, empathy and confidence, just to name a few.”

And I do suspect that if someone tries to take a driving test using a self-driving car, the DMV might not accept it, and it would indeed be problematic if they gave that person a license. I don’t know that anyone has tried, though!

I think that using online translators should be integrated into the language classroom. The same way we used to teach students how to use a dictionary, we must include a section on good practices with online translators.