Online Translators as a Pedagogical Tool

Andie Faber, Assistant Professor of Spanish, Kansas State University

|

Maria Turrero-Garcia, Visiting Assistant Professor of Spanish, Drew University

|

Introduction

Online translators (OT) such as Google Translate are constantly increasing in their accessibility and accuracy, two very enticing qualities for language learners who seem to be drawn to them like a moth to a flame. Language instructors, on the other hand, tend to balk at the idea of allowing students to use OT in their course work. This disconnect between instructor and student perceptions of OT use has been a source of frustration among the former population and confusion among the latter. In this article, we outline findings from a language instructor survey about their policies and perceptions with regard to OT as well as survey data of attitudes and beliefs held by language learners. We offer a classroom treatment designed to give students an opportunity to analyze linguistic forms under study and gain personal experience with the advantages and disadvantages of OT. We report student responses to the classroom activity as well as shifts in attitudes towards OT as evidenced in a post-treatment survey.

Online Translators and Language Learning

Online dictionaries differ from online translators in that an online dictionary accessed through a web browser and allows the user to search its entries by typing the desired lexical item into a search box. This process offers immediate access to the word’s meaning(s) in addition to a host of ancillary information such as part of speech and related features, inflected forms, examples, and common expressions and idioms in which the word is found. An online translator, on the other hand, produces text in one natural language from that of another using computational procedures and algorithms via a web-based platform.

OTs have been available free of charge to any language learner with an internet connection for approximately 20 years now. Somers (2001) asserts that “inasmuch as translation is often part of foreign language learning, we can say that learning about [Machine Translation] tools should be part of the curriculum for language learners” and though this quote was written nearly 20 years ago, little headway has been made in incorporating Machine Translation as regular component of the L2 learning experience.

While the OTs of 20 years ago were quite crude in their capabilities, this technology is rapidly improving in accuracy. Modern OTs tend to produce accurate conjugations, spelling, basic agreement, and some common idioms (Correa, 2014). However, even Google has admitted that “the accuracy of the translation depends on the language translated” (McGuire, 2018). Theoretically, translating between languages that are typologically similar should produce more accurate results, but even when two languages share the same root, such as Spanish and Portuguese, the OT can still encounter numerous problems, such as ambiguity, polysemy, gender, and register (McGuire, 2018; Correa, 2014). Additional limitations often found with online translation is that they produce very literal translations, they cannot interpret misspelled words, and they produce discursive inaccuracies (Correa, 2014).

When it comes to L2 learners, one serious problem is that OTs promote a “naïve view” that there are one-to one equivalents in the L1 and L2 (McAlpine & Myles, 2003). Additionally, the ease with which students can access translations for full sentences, paragraphs, or even longer texts can have a disincentivizing effect on students, who may use OTs as a shortcut to complete their homework, as recognized by both students and educators who took part in surveys for the current study.

Although there are numerous limitations to OTs, there has been promising work in recent years that indicates that when used in conjunction with some type of training, OTs can be an effective pedagogical tool. Enkin and Mejías-Bikandi (2016) assert that teachers can use faulty OT output to highlight and reinforce patterns of the L2 and to examine grammatical differences between the L1 and L2. O’Neill (2012) examined the effectiveness of an OT training program as part of an L2 French writing curriculum and found that the group that received OT training demonstrated improved results in their L2 writing.

Instructor Survey

This study emerged after numerous conversations with colleagues in L2 instruction who expressed frustration and dismay at the seemingly unstoppable tide of OT use (and misuse) amongst students. In order to go beyond anecdotal evidence, we created a survey which was distributed to Spanish language instructors (n=32), recruited through social media groups for language instructors. The most common courses these instructors taught were: intermediate-level (84.4%), novice-level (62.5%), linguistics courses (56.3%) and other advanced-level courses (50%). These percentages add up to more than 100% as many instructors teach multiple levels.

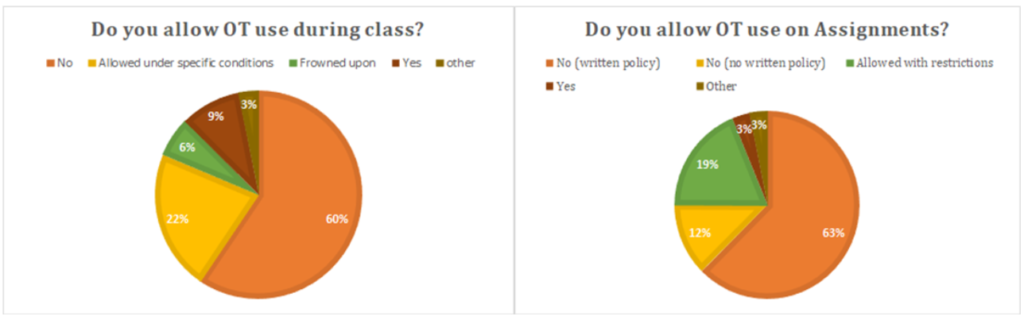

Participants were asked about their course policies related to OT use, their perception of their students’ use, and the impact of OT use on L2 development. Of the instructors surveyed, 60% said that they do not permit use of OTs during class time, while only 9% allow it. The remaining 31% of responses indicated that OTs are only permitted under specific conditions or that their use is discouraged, but not disallowed. When it comes to assignments, 63% of respondents stated that they do not allow OT use on assignments and they had a written policy stating as much. An additional 12% reported that they do not allow for OTs on written assignments, but they had no written policy in place. Only 3% of instructors surveyed stated that they permitted students to use OTs for course assignments without restriction.

When asked about their perception of students’ use of OTs, instructors’ responses indicate that they feel that OT use is common among students. Reporting on their in-class use of OTs, 75% of instructors believe that students are using OTs at least occasionally in class. When it comes to course assignments, 94% of instructors believe that their students are using OTs at least occasionally.

When instructors were also asked how OT use affected student L2 development, 42% reported that they believe that it had some type of negative impact on development, 23% stated that they believe its effect is neutral, and 19% stated that OTs were beneficial to L2 development. The responses of the remaining 16% were more nuanced. For instance, one respondent stated “they can be beneficial but most of the time it is used as a shortcut for activities, preventing the students from getting the most out of the exercise.” Several respondents indicated that the effect of OT use on development depends on how these tools are used and some stressed the importance of teaching students how to use OTs as a tool in the language learning process.

At the end of the survey, participants were prompted to include any additional thoughts they had on OTs. Instructors voiced a range of opinions. Some reiterated the importance of teaching students how to use OTs. Multiple instructors commented on student reliance on OTs as being problematic, noting that the issue is that students are plugging in text to the OT and copying the output without thinking critically about it. The frustration among some instructors is encapsulated in one response: “Are we fighting a losing war? It is so frustrating and stressful to have to confront students about using translators, and yet nothing we say or do seems to discourage their use.”

The current project is aimed at addressing this final comment. We approach pedagogical implementation of OTs from a Constructivism Learning Theory perspective (Vygotsky, 1972; Piaget, 1980; Bada, 2015). According to this approach, the context in which something is taught affects student learning as do students’ attitudes and beliefs. Humans construct knowledge and meaning from their experiences. As such, for this project, we consider student attitudes and beliefs related to OTs and provide them with experiences to shift erroneous beliefs and construct a deeper knowledge of linguistic content as well as knowledge and understanding of how OTs work and how students can use them effectively.

Student Survey

In order to assess student attitudes and beliefs related to OTs and gauge their reliance on OTs for course work, we conducted a survey with second-semester Spanish language learners (n=27). Students were first asked if they used online dictionaries to look up words they don’t know in Spanish, to which over 80% of students reported that they did. When asked which dictionaries they used, 68% reported using SpanishDict (a Spanish-English OT), 36% reported using Google Translate, and 9% reported using WordReference. Of these, only WordReference is a true online dictionary.

Next, students surveyed were asked if they use OTs to look up words they do not know. To this question, 63% responded yes, then wrote in the same responses that they had written for the first question and 15% admitted that they were unsure as to the difference between this question and the previous one. The response to these two questions provides crucial information related to student attitudes and beliefs. It suggests that telling students “you may use an online dictionary, but not an OT” may not make sense to them.

Students were also asked how often they use OTs for class, to which 85% reported using OTs at least occasionally, of those 19% reported using OTs for most class assignments and 40% reported using OTs on approximately half of the course assignments. When asked what they liked or disliked about OTs, speed and ease of use were the two most commonly cited benefits of OTs. In terms of what they dislike, students most often noted that OTs are not always reliable and several commented that OTs function as a crutch that can undermine the learning process.

Classroom Treatment

To assess the value of OTs as a pedagogical tool, both in educating students about the translator’s (un)reliability and in developing metalinguistic awareness through contrastive grammatical analysis, we designed a classroom treatment aimed at enhancing students’ analytical thinking both in terms of translator use and of grammatical structure.

Methods

College students enrolled in a second semester Beginner Spanish course (n=25) at a University in the northeastern United States participated in this treatment. It was presented as a classroom activity within the context of the Spanish preterit vs. imperfect aspectual distinction, in a textbook chapter that had “shopping” as its main vocabulary focus. Prior to completion of the class activity, students had approximately 6 hours worth of in-class exposure to and practice with both the vocabulary presented in the unit and the distinction between the preterit and the imperfect, for which they received theoretical explanations paired with copious practice.

Translator activity

Participants were divided into groups of 2 or 3 students for a total of 9 groups. Each group was given an English sentence (see Example 1) that contained shopping vocabulary and past tense meaning. Each student in the group ran their sentence through a different OT (Google Translate, Babelfish, and SpanishDict). After all translations were obtained, students were asked to compare their sentences focusing specifically on (a.) the choice of verb tense for each translator, (b.) the main differences between translations (as an open-ended question, where they could make observations about grammar but also about lexical choices), and (c.) they were asked to choose either one of the translations provided by an OT or create their own translation of the sentence.

Example 1. English sentence and OT translations (differences in tense are marked in bold; difference in lexical choice are underlined):

“Rubén used to buy new shoes every month, but since he lost his job, he stopped shopping for new items”

| Google Translate | Rubén solía comprar zapatos nuevos cada mes, pero como perdió su trabajo, dejó de comprar artículos nuevos |

| SpanDict | Rubén solía comprar zapatos nuevos cada mes, pero desde que perdió su trabajo, dejó de comprar nuevos artículos |

| Babelfish | Rubén compraba zapatos nuevos cada mes, pero como perdía su trabajo, dejaba de comprar artículos nuevos |

Table 1: OT translations for sample sentence

The sentences in this study were created to showcase different aspectual uses of the past tense (such as habitual aspect -typically imperfect- and beginning and end of an action -typically preterit- in Example 1), which are not expressed overtly in English but they are in Spanish through the use of preterit or imperfect verb forms. Since this distinction is not present in English past tense verb forms, this can be a difficult concept for Spanish L2 learners. All sentences also incorporated vocabulary related to shopping to reinforce the thematic content of the chapter. The test sentences were run through all three OTs and found to provide different translations of the verbs as well as some other lexical and grammatical differences. In this way, the variation in translation output provides ideal material to test students’ understanding of the fine-grained aspectual distinctions studied in this part of the course as they analyze the differences.

The major objectives for this activity are that students (1) think critically about language use and OT output, (2) recognize their own linguistic abilities, and (3) gain understanding about the strengths and weaknesses of OTs (including being disabused of the “naïve view” that there are one-to-one equivalents between the L1 and L2).

Results and Student Reactions

The results obtained from this study are split into four distinct categories: 1. Identification of incorrect tense use, 2. Translation errors identified, 3. Final choice in translation, and 4. Post-activity survey.

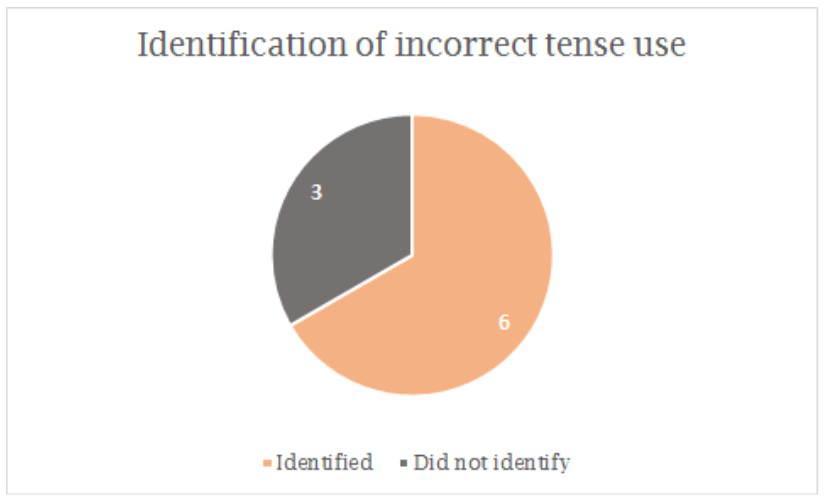

Identification of incorrect tense use

Out of 9 groups of students, 6 (67%) were able to correctly identify when a translation missed nuances in the distinction between the preterit and the imperfect (be that an entirely ungrammatical use or a pragmatically inadequate choice).

Example 2. Translation pair for sample presented in Example 1:

Rubén solía comprar zapatos nuevos cada mes, pero como perdió su trabajo, dejó de comprar artículos nuevos.

vs.

Rubén compraba zapatos nuevos cada mes, pero como perdía su trabajo, dejaba de comprar artículos nuevos.

Student feedback on Example 2 was mixed: while many of the groups correctly identified the second translation as being less accurate (student group 1: “[The second half of the sentence] starts a beginning of an action or the end so it makes sense that perder and stopped are in the preterit), some students did not grasp the full intricacies of the sentence provided with regards to the contrastive use of the preterit to express a change in the past in the second half of the sentence, overextending the semantic content from the first clause to the verbs in the second (student group 2: “We think the imperfect is better since buying new shoes every month is habitual”). However, even when the analysis provided may be considered off-target, students are employing their metalinguistic knowledge to come to conclusions in their comparison of OT productions. It is the teacher’s role, in this case, to provide students with feedback in order to steer them to a reanalysis and reinterpretation of the sentence based on other nuances of the preterit/imperfect they have learned.

Translation errors identified

Students were given freedom to identify anything they found odd or incorrect in this section of the assignment. Aside from the 6 tense choice errors mentioned above, participants identified errors or inaccuracies with respect to idiomatic expressions (i.e. direct, word-by-word translations of expressions that do not retain their meaning in Spanish), lexical differences (i.e. vocabulary choices, particularly in relation to the vocabulary learned by this group in their textbook), and other grammatical errors unrelated to verb tense (see Example 3).

Example 3. Translation pair for the English sentence The sales clerk was very insistent, so you ended up buying the shirt she offered:

El empleado de ventas fue muy insistente, así que terminaste comprando la blusa que ella le ofreció

vs.

El vendedor fue muy insistente, así que terminaste comprando la blusa que ofreció

Group 3 very clearly identified an error in the OT’s use of indirect object pronouns: “One used le and not te as the indirect object pronoun and the others did not use an indirect object pronoun. They are all equally bad.” This shows that an activity such as this can go well beyond specific grammatical points and extend to the students’ overall command of the Spanish language, giving them a chance to observe and reflect on multiple aspects of the grammar and vocabulary that are often disregarded when micro-focusing on specific structures.

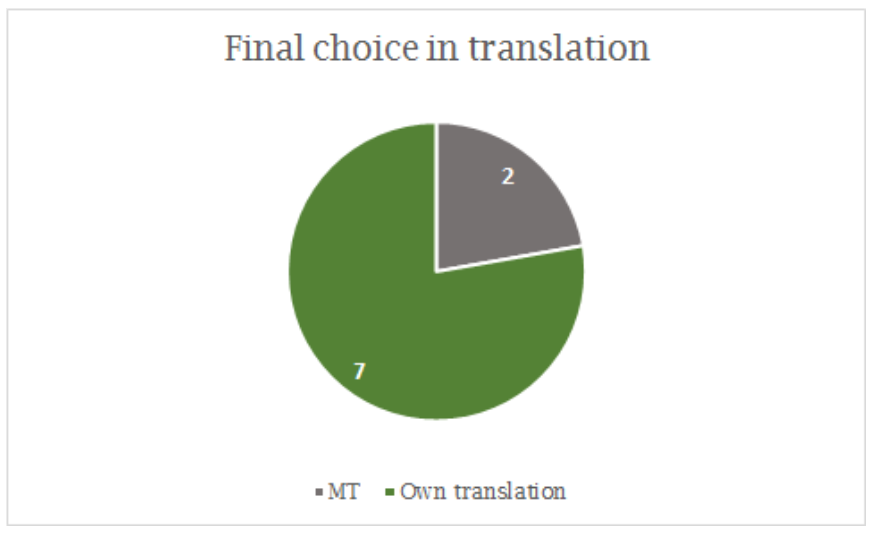

Final choice in translation

Over 75% of students who participated in this classroom activity, when given the option between selecting a translation from an OT or coming up with their own, chose the latter. This indicates that understanding the shortcomings of OTs can have an impact on student awareness and use of this tool. Example 4 clearly shows how students can use their metalinguistic knowledge to improve the translations that they are exposed to through the use of OTs.

Example 4. OT and student translation to the English sentence The sales clerk was very insistent, so you ended up buying the shirt she offered:

GT: El empleado de ventas fue muy insistente, así que terminaste comprando la blusa que ella le ofreció.

SD + BF: El vendedor fue muy insistente, así que terminaste comprando la blusa que ofreció

Student translation: Tú compraste la blusa que el dependiente te ofreció porque él era muy insistente

Results from this section of the activity suggest that engaging in this type of project can empower students as they recognize that they are able to produce more appropriate translations than the OTs. These results are supported by data from a post-activity survey, reported below.

Post-activity survey

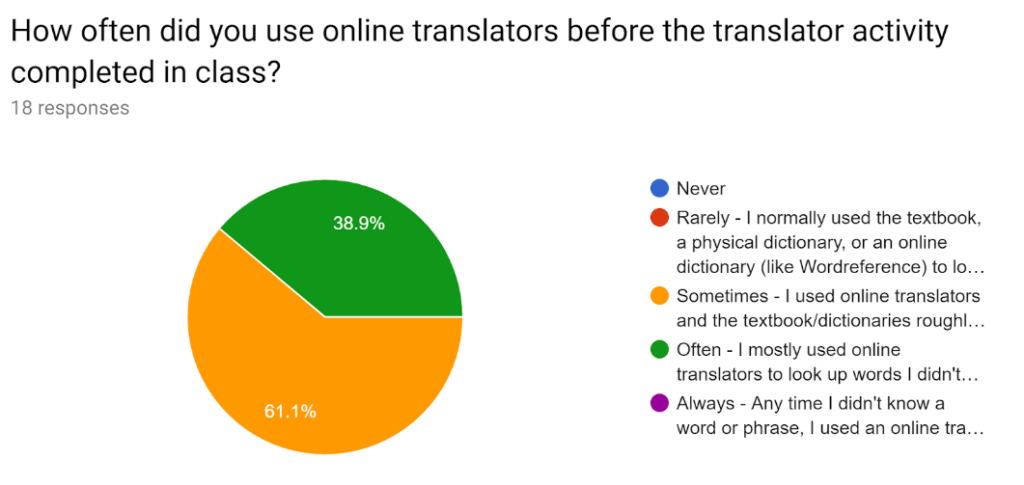

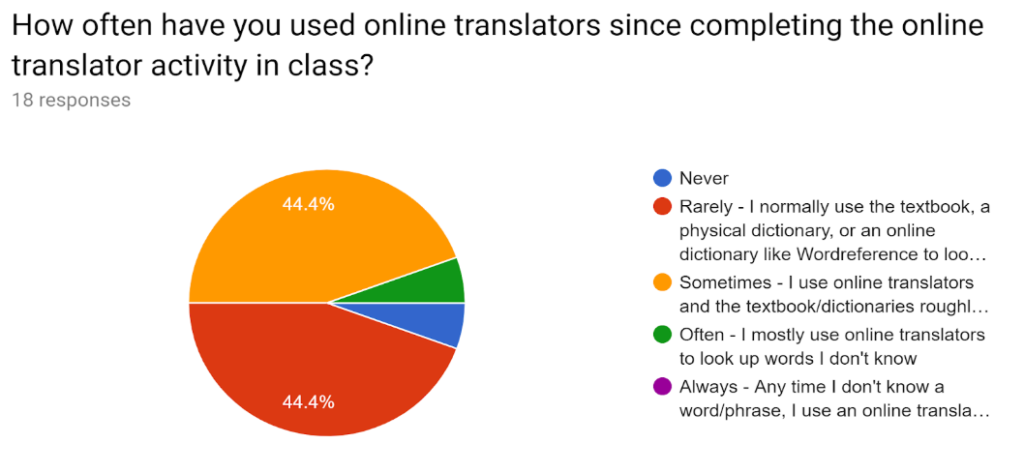

Following the classroom activity described above, students were encouraged to participate in an anonymous survey created to gather information on their previous use of OTs, their use or plan to use OTs post-classroom treatment, and their overall opinions (including shifts in perspective) on the use of OTs in language learning. Students report a notable shift in OT use from pre- to post-classroom treatment, as represented in Pictures 5 and 6.

All survey participants reported using OTs in class or for assignments before completing the classroom treatment, with as many as over 35% of students claiming that they used them often. However, when asked about their uses post-treatment, we see a noteworthy reduction in usage of OTs, with half of the participants having lowered their use of OTs to never or rarely and only 5.6% of participants report that they continue using OTs often. These results were complemented by an open-ended section in which students were asked the following question:

If one of your friends in SPAN 102 told you that they were planning to use an online translator to complete a writing assignment they had, what advice would you give them?

The responses obtained suggest that the classroom treatment presented in the current study had the effect that the authors were hoping for: students are aware of the inaccuracies of online translators; they suggest contrasting them with their own knowledge and intuitions; and even go as far as vehemently discouraging others from using them:

- “I would tell them to be careful or just not use it because [it] would not know what tense you are supposed to use for the writing assignment.”

- “Make sure to read the translations carefully and don’t [rely] on it too much. You should use the translator for words and not much more than that.”

- “The translators suck and you have a better chance not using them”

- “Don’t. 1. It’s cheating, so it’s wrong. 2. There will certainly be errors, and will you be able to catch them? 3. The teacher will catch them and know what you did.”

Providing students with experiences using and analyzing OT output allow them to construct knowledge and shift their beliefs and attitudes related to their use. The results from the current project are highly encouraging; however, contrary to our expectations, numerous students reported that OTs are fine when used for single words (as opposed to entire sentences). While at first this result was surprising, this activity provided us, as language instructors, with additional information about students’ attitudes and beliefs. We see that their attitudes are starting to shift to be in line with those of the language instructors; nevertheless, we cannot expect to change attitudes and beliefs with one classroom activity. Now that we know that many students still believe that OTs are valuable for single-word translations, we can create an additional OT class activity that focuses on single word use. By tapping into our students’ beliefs, we can more effectively teach them the information we want them to know.

Conclusion

As language instructors, we should consider our students’ goals and how we can prepare them to use their L2 in the real world. Considering that OTs are easily accessible and can be extremely useful, it is in our best interest to find ways to work with OTs rather than continually discourage their use. Providing students with training and experiences using OTs in a controlled setting, such as in the activity presented here, can help students avoid confusion and “accidental cheating” (i.e., a lack of awareness of how OT use can constitute academic dishonesty). These types of experiences can also empower students to rely on their own linguistic abilities rather than enter their text to an online translator.

There are, however, some challenges related to incorporating OTs in the L2 classroom. One of the most serious ones is that OTs are constantly changing and improving. The algorithms that OTs use to convert text from one language to another are designed to “learn” from examples, which means that the way an OT translates a particular sentence today may be different from the way it translates that same sentence next week. Despite these challenges, we believe that the value that incorporating OTs as a pedagogical component of a language course is well worth investing time and energy. Additionally, we feel that these types of activities should be introduced early in the language learning process, but taking into careful consideration the design of the task. At the early stages of language learning, the focus of such tasks should center around vocabulary, simple sentences, and basic grammar points. As the students advance in their linguistic development, these tasks can be expanded into more complex linguistic constructions that could even require students to provide support for their analysis of the online translator output using other online language tools. We strongly feel that online translator activities, such as this, as well as additional activities that create experiences with online dictionaries and other web-based language tools should be incorporated throughout L2 courses.

References

Bada, S.O. (2015). Constructivism Learning Theory: A paradigm for teaching and learning. IOSR Journal of Research & Method in Education (IOSR-JRME), 5(6):1, 66-70.

Correa, M. (2014). Leaving the “peer” out of peer-editing: Online translators as a pedagogical tool in the Spanish as a second language classroom. Latin American Journal of Content & Language Integrated Learning, 7(1), 1-20. doi: https://doi.org/10.5294/3568

Enkin, E. & Mejias-Bikandi, E. (2016). Using online translators in the Second Language Classroom: Ideas for Advanced-Level Spanish. LACLIL, 9(1). 138-158

McAlpine, J. and Myles, J. (2003). Capturing phraseology in an online dictionary for advanced users of English as a second language: a response to user needs. System, 31(1), pp. 71-84.

McGuire, N. (2018). How Accurate Is Google Translate in 2018? Argo Translation (online resource).

O’Neill, E. M. (2012). The effect of online translators on L2 writing in French. Doctoral Thesis. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Piaget, J. (1980). The psychogenesis of knowledge and its epistemological significance. In Piatelli-Palmarini, M. (ed.), Language and learning (pp. 23-34). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Somers, Harold (2001) “Three Perspectives on MT in the Classroom”, MT Summit VIII Workshop on Teaching Machine Translation, Santiago de Compostela, pages 25–29.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: the development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge: MA: Harvard University Press.

In an effort to get my students to use the vocabulary and grammar that they already know, especially since I only assign items that would rely on their prior and present knowledge, when possible, I always do writing activities during class time. That way, I can see where they are going right, meaning that they are simply looking up nouns, infinitives, adjectives and other specific parts of speech, and where they are going wrong, they plug in whole sentences or even paragraphs. When they ask for too many consecutive words, the translating devices do not understand their misspellings or grammatical misuses in English, and they end up with all kinds of convoluted nonsense.

I have stopped to give them a grand lesson on how to use an online translating device in a reasonable way. I show them what they may look up, and how to know if they got the correct word or phrase by cross referencing back to English. That is always an eye-opener for the students.

Finally, when I assign a writing activity created to make the students use the past and current topic vocabulary and grammar, should they come up with all kinds of new phrasing, I ask them if they would like to have all that additional verbiage added to the unit items for an upcoming assessment. It is like magic to have them get that light bulb over their heads and then revert to using the stuff in the original assignment with no further prompting. The point in any L2 acquisition activity is that they practice and get correct everything that they already know while adding new vocabulary and grammar at an appropriate pace to their abilities at their level. Online translators drown learners in native level words and locutions which is like pouring an ocean on top of a sponge and expecting it all to be absorbed.

That is my two cents, for what it is worth.