A How-to for Hybrid Conferences (Revisited)

Jonathan Perkins (University of Kansas) |

Marlene Johnshoy (University of Minnesota) |

Dan Soneson (University of Minnesota) |

Shannon Donnally Spasova (Michigan State University) |

In March of last year we reported on a new conference model that the Midwest Association for Language Learning and Technology (MWALLT) was developing to increase the reach of its annual conference. We had found that our conferences were not of sufficient size to attract people from more than a few hours driving distance from the conference venue, and that attendees from one year were unlikely to attend the next year as the conference moved from state to state. The result was a small conference with a shifting set of attendees where people could make face-to-face connections with colleagues within a very limited geographic area.

Our new hybrid model attempts to bridge that gap by using teleconference to share presentations among sites throughout the twelve states that MWALLT represents. The hope is to create a conference that allows the exchange of ideas in both face-to-face and distance formats, preserving the feel of the local conference while broadening the range of presentations available by engaging the entire region. We share here our evolving thoughts on this new hybrid conference format.

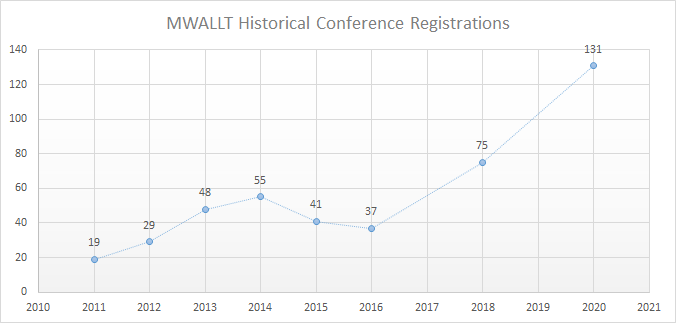

There is no doubt that the new conference format has increased the number of registrations for the conference. By moving to the hybrid format in 2018, we doubled the number of registrations, and the 2020 conference saw a similarly impressive jump. Indeed, since moving to the new format we have seen conference registrations more than triple.

Conference evaluations have also shown overwhelming support for the new format. Over 90% (54 out of 58) of respondents indicated that they agreed (17) or strongly agreed (37) with the statement “I liked attending this multi-host conference.” When asked about the positive aspects of the format, most focused on the convenience and cost-savings of participation at a local venue or completely online, but nearly as many noted the impressive range of presentations afforded by sharing speakers across the host campuses. Participants also appreciated the ability to network face-to-face at a local host or hub while also having access to presentations (and presenters) at remote sites. Just short of 88% of the respondents (51 of 58) also indicated that they agreed (18) or strongly agreed (33) with the statement “If this were an annual event, I would attend every year”, boding well for the 2021 conference already in the planning stage.

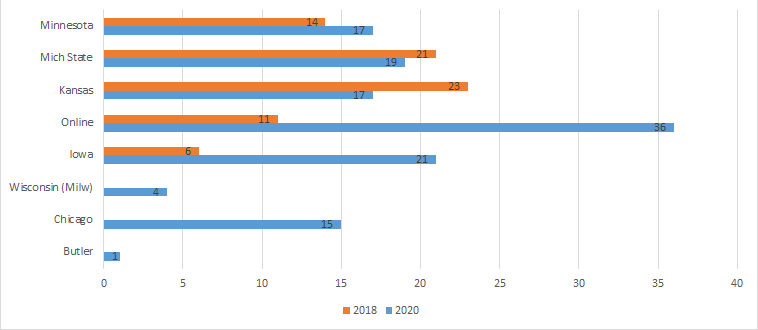

As overall attendance for the conference spiked, collective attendance at the three original host sites (the University of Kansas, Michigan State and the University of Minnesota) held roughly even. The University of Iowa, which joined the 2018 conference as a hub (receiving but not sending presentations) actually had the largest number of in-person attendees in 2020 as it made the transition to a host site. The University of Chicago, which joined as a hub alongside the University of Wisconsin – Milwaukee and Butler University, also had in-person attendance nearly equal to the three original hosts.

The addition of a fourth host and three new hub sites provides much greater coverage of the twelve-state MWALLT region, although some additional sites in the Dakotas (and perhaps the area around Saint Louis) would help to even out the coverage even more. The largest single driver of the increase in attendance for the 2020 conference was, however, individual online attendees.

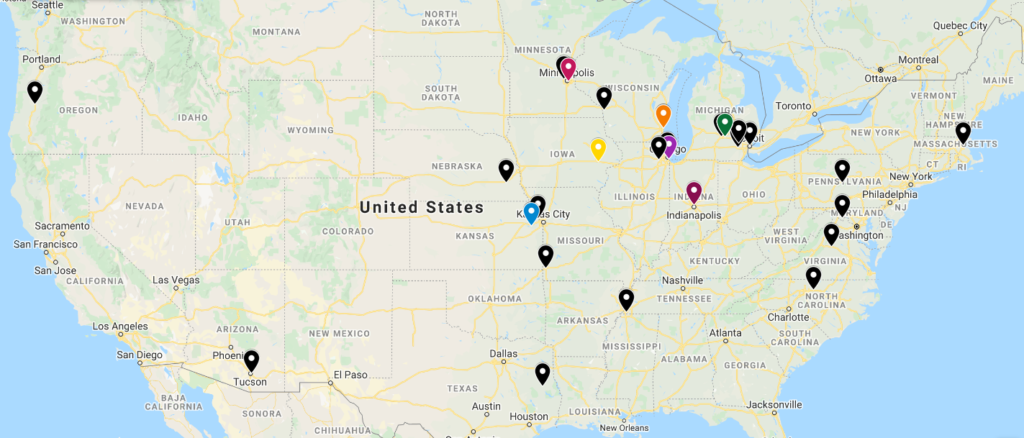

While these virtual attendees were certainly a welcome addition, it should be noted that individual online attendance was largely an afterthought made possible by the streaming platform. The explicit goal of the hybrid format was to preserve the face-to-face interaction of the small regional conference but to expand it to a larger number of sites; the use of teleconference was intended solely to establish links between those sites. The map below illustrates the geographical location of the individual remote attendees in black, with the hosts and hubs marked in color.

There are two major items of note in looking at the map. The most obvious is that moving the conference online has opened it to an audience far wider than the Midwest, leading to interesting discussions of whether the “regional” nature of the conference is something that may continue to recede. If the conference continues to grow, it is easy to envision a university outside of our twelve-state region requesting to be a host or hub, increasing the reach and scope of the conference even further.

The second item of note is that there are remote attendees in very close proximity to many of the hosts. It is unclear how many of those attendees might have attended the conference in person if that had been the only option, but we know anecdotally that the online option allowed attendees to work around last-minute issues of illness and weather that might otherwise have prevented their participation. The availability of online recordings is also likely to be a major help to those who may have intermittent ability to attend sessions, or may find themselves wanting to attend more than one presentation during a particular block of time.

From the beginning of this new hybrid model, we have made it a requirement that presenters be physically located at one of the host sites to ensure the most effective technical support; as part of the proposal submission process, presenters were required to indicate at which host site they would present. The ability to present at multiple sites has helped to increase the number of proposals submitted, with the 2020 conference receiving 36 total proposals, nearly twice the number of the strictly in-person conference in 2016. Indeed, the number of high quality proposals led to an expansion of the conference from two simultaneous streams in 2018 to three in 2020. Hosts and hubs provided separate physical rooms for each stream and online attendees needed to log in and out of separate virtual rooms depending on their choices of presentations; all events intended for the entire group, including the keynote speaker and the business meeting, were hosted in a single room.

As at the 2018 conference, there was an interdependence among the hosts at the 2020 conference with regard to accommodating speakers. A presenter from the University of Kansas presented on the Michigan State stream with tech support at the two locations negotiating logistics. The presenters from the University of Iowa were likewise split between the Kansas and Minnesota streams, but the transitions back and forth were basically seamless for anyone watching the presentations. With screen sharing available through the teleconferencing platform, remote audience members viewed the same content as those in the room with the speaker, and audiences at hosts and hubs viewed that content on the same big screen as they would have if the presenter were presenting locally. Audience members could also ask questions of the speakers with equal facility whether they were in the same physical location or not, although most remote audience members seemed to default to asking questions via the chat interface of the teleconferencing platform.

The flexibility to handle speakers coming from various locations proved quite valuable when several speakers who had originally registered to present at a host site found themselves unable to make the trip in the days before the conference. Those presentations were still included in the program thanks to the quick work of the local tech staff in testing audio feeds and facilitating transitions on a group presentation with a local and a remote presenter. The ability to connect with remote presenters was perhaps most valuable in allowing us to kick off the conference with a keynote presenter who happened to be visiting the United Arab Emirates during the conference. There is little doubt that the technological underpinnings of the conference are solid and provide opportunities to expand our thinking about what is possible going forward.

There is, however, a centrifugal pull of technology that complicates the evolution of the hybrid model. Now that the conference has shown that it can accommodate presenters from outside of the host sites without too much logistical complication, we must consider whether to allow such proposals from the outset. We must also consider whether the desire to make participation as easy as possible may lead to a predominance of individual remote attendees, threatening to turn the conference into an all-day webinar where most presenters are dealing primarily (if not exclusively) with remote audiences. As our geographical reach expands, our major obstacles are likely to be preserving the centrality of the host sites and creating greater opportunities for networking across sites and among local and remote attendees.

We had envisioned some multi-site panels as one way to bridge the physical distance at the 2020 conference, but did not receive any suitable proposals and will need to be more intentional in soliciting those kinds of submissions for the next conference; the “lightning talk” session, which included brief presentations from both Iowa and Minnesota presenters, did provide some foundation for further experimentation. We also attempted to increase the sense of connection among the attendees by starting the conference with virtual breakout rooms for remote attendees to network (albeit briefly) with those at the host and hub sites. Attendees (local and remote) were also encouraged to use the chat function within the teleconferencing platform for backchannel conversations during presentations. As online attendees noted a feeling of remoteness and lack of opportunity to interact meaningfully with the on-site attendees, we will need to explore new ways to recreate that sense of community. One possibility that has already been suggested is to reinstate the catered lunch at the host and hub sites, and perhaps to open up special interest “rooms” to facilitate less structured conversations on topics of shared interest among local and remote attendees.

As we expand our attendance and provide access to a wider range of presentations, we are left to wonder what a regional conference should look like in the 21st century. Do shrinking travel budgets, new threats of pandemics, and ecological concerns about long-distance travel make fully online conferences the most effective means of scholarly exchange? Can we effectively preserve (or recreate) the valuable interactions made possible by face-to-face conferences, including those less formal interactions that often serve as the foundations for collaboration? Only time will tell.