Making Your Tech Projects Salvageable and Sustainable – the Case of the RAILS Project

By Shannon Donnally Quinn, Michigan State University

DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.69732/DDGH4005

If there is one thing that educational technologists know, it is that no technology lasts forever. Some of the closets of our language centers are museums for technologies that have fallen by the wayside: filmstrips, opaque projectors, cassette tapes. So it was no surprise when it was announced that Adobe Flash would be phased out at the end of 2020. But still, the demise of Flash left quite a few good projects behind in the dust. This article will be a brief accounting of the rescue of one project amid the fall of Flash, as well as some thoughts about how to make future projects salvageable from whatever technology changes may come in the future.

The RAILS Project

The RAILS Project (Russian Advanced Interactive Listening Series) was a project at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, funded by a grant from the U.S. Department of Education International Research and Studies Program. Benjamin Rifkin was the Principal Investigator, Dianna Murphy was the Project Manager, and I, along with Victoria Thorstensson, Nina Familiant, and Darya Vassina, were graduate Project Assistants who worked on the project between 2003 and 2006. Over the three years of our work, we developed 30 lessons based on documentary films and interviews with prominent Russians on topics such as the first Soviet labor camp, the Taganka Theater, gender issues in Russia, nationalities in Russia, and the 2004 presidential elections in Russia. These lessons aimed to help learners of Russian get from the Intermediate to the Advanced level on the ACTFL scale in listening proficiency. The project won the American Association of Teachers of Slavic and East European Language “Best Contribution to Language Pedagogy” prize, and continued to be used in Russian classrooms even more than a decade later.

When we realized that the demise of Flash would also be the demise of our project, the team met and decided that the project was worth a rescue effort. Russian is a language that already has a dearth of materials for the Advanced level, so to let this project and the mountain of work that it had taken to produce it just fall by the wayside would certainly be a loss for the field.

Team members (Shannon Donnally Quinn, Benjamin Rifkin, Dianna Murphy, Karen Evans-Romaine, Victoria Thorstensson, and Anna Tumarkin) volunteered varying amounts of their time to the project, and the Russian Flagship Program was able to fund some hours of work from two graduate students (Lidia Gault and Isabella Palange).

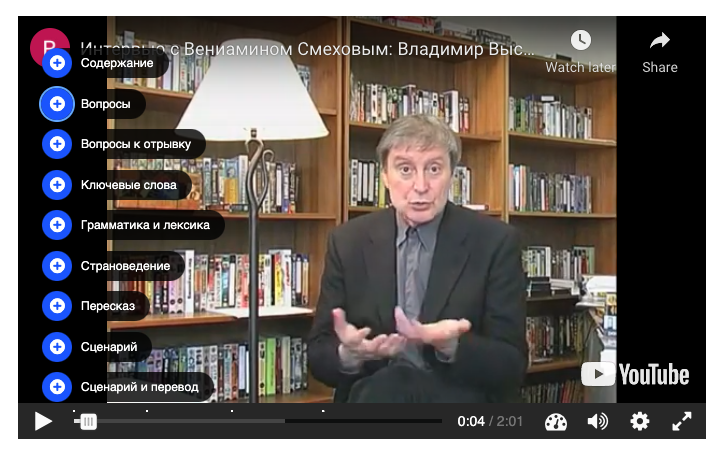

The initial set of lessons had been created using two pieces of Flash-based custom software developed at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, called the Multimedia LessonBuilder and the Multimedia Annotator. By 2021, those tools were no longer in use, but over the ensuing years much of their innovative functionality had become easier to find in tech tools readily available to faculty and designers, such as YouTube, Pressbooks, and H5P, all platforms that we had access to. Some workarounds had to be found for some of the more unique features of the original lessons, but the majority of functionality had relatively easy-to-identify equivalencies in the newer applications. We debated whether to make more substantive changes to the lessons based on affordances of the new software that did not exist in 2006. In the end, however, we decided that given the limited resources of the project, we would mostly keep the lessons similar to their original form and content. Expanding the content is, however, something we are open to exploring in the future.

Make Your Projects Salvageable

When we develop technology-based projects, we know that technology will change. Unfortunately, the funding model for many projects does not last beyond initial development. To make the most efficient use of our time and resources, this is a practice that we should reconsider. The RAILS Project was not different in this sense, but fortunately there were several groups that were willing to dedicate time and resources to the rescue of the project over 15 years later. There were also some intentional decisions made during the creation of the RAILS lessons that made it so that the project was able to be rescued more easily. I will outline some of those decisions here in the hope that this may help others to create projects that are more likely to be able to be resurrected when the inevitable technological obsolescence happens.

Hosting

While the team members from the original RAILS Project have spread out over the globe in the period after the initial launch of RAILS in 2006, the project continues to be hosted at the University of Wisconsin-Madison Language Institute. Identifying an organization that will remain dedicated to the hosting of the project despite possible changes in the affiliation of the individual members is essential. The investment that a particular organization has made to a project and how that will unfold in years to come should be considered and negotiated as part of the project’s initial development and implementation.

Intellectual Property Rights

As an initial step in the original project, the RAILS team worked with University of Wisconsin-Madison Office of Legal Affairs to create work-for-hire agreements for all members of the project team who contributed to the development of the lessons, permissions for interview subjects, and agreements with the copyright holder of the films that were used in the lessons. With copyright of the lessons thus “bundled” and assigned to the university, it was possible to update the lessons years later without having to navigate complex questions about who had the rights to make those modifications.

Media

Various pieces of media that are integrated in a project should be stored in their original forms somewhere separate from the project itself. In our case, we had redundant backups, which included original digital tapes of interviews, and CDs and DVDs with copies of the full videos from which we had extracted the video clips that formed the basis of our lessons. Since the Flash .swf files were no longer usable after the demise of Flash, it was necessary to create new versions of the clips. This was desirable also because the .swf files were necessarily smaller in size considering bandwidth limitations back in 2006 when the first iteration of the RAILS Project was launched. In preparing the new versions of the video clips, now hosted on YouTube, we were able to enhance them (mostly to reduce background noise), improving their quality. Audio clips and images were also stored and easily retrievable, making recreation of the lessons much easier.

Because the Flash player had a definite expiration date, we knew which aspects of our project had to be rescued first – it was the part of our lessons called the “Listening Assistant,” because its technology relied completely on the Flash player. We recreated these first, knowing that we might no longer be able to after December 2020. Though we had done quite a thorough job of archiving the different pieces of media, the text that was included within the Listening Assistant (key words, guiding questions, glossaries, cultural information, and the like) was not backed up outside of the lessons. Because we reacted in time, it ended up not being problematic, but in the future I will keep this challenge in mind as I document my projects.

Naming Conventions

While we developed the RAILS Project, we were intentional about developing a naming convention. It was not complex (lessonname_pagename_questionnumber), but it made it possible to find files without having to listen to or watch them all, which was a huge time saver. While we were not perfect and there were a few files that I had to search for or remake from the master copy, overall the process went quite smoothly because of this attention to detail that we had prioritized while developing the project. This was one of those times when I really thanked “past me,” as well as the wise people who had presciently set up the project in such an organized manner!

Challenges

While there were many things that we did well, there are still some things that would have made rescuing the project easier.

Point of View

When we created the lessons, we wrote from the point of view of the present day at that time. Some of the lessons concerned current events (in particular an interview with Irina Khakamada, a politician who ran against Vladimir Putin in the 2004 Russian presidential election). In the revisions of the lessons, some of the language needed to be changed to make it clear that certain things were no longer true, for example. In creating future projects I will try to keep this in mind as I craft the language in the lessons.

Durability of Content

It can be impossible to predict how well particular content will hold up over time. Ideally you may want to plan for a future revision to make your content outlast its expiration date. In our case, much of the content was somewhat historical in its point of view, which has helped it to continue to be relevant. However, if we are able sometime in the future, it would be extremely interesting to further frame some of the materials. For example, one of the films that our lessons are based on was made in the late 1980s about events that occurred in the 1920s, and looking back on both of the time periods from 100 years later can provide an additional interesting layer. It would be fascinating to look back at the interview with Irina Khakamada, which was current at the time that the RAILS Project was made, through the lens of what has happened since her run for president in 2004. Teachers using the content in their courses are most likely doing this anyway, and finding a way for them to share their approaches with each other might allow the content to evolve without having to invest a great deal of time into constantly revising the lessons themselves. If we are able to build on this project in the future (an option that we are exploring), we could consider setting up an online community of people who use the lessons who could share ideas about how to continue to adapt the materials to new circumstances.

Specificity of Resources

Many of our lessons included references to outside resources that could be used to extend the lessons further in the classroom. When revisiting the lessons, we discovered that many of these resources are no longer available. While this is inevitable, in future projects I will consider being more general in the suggestions for resources or perhaps including links from the Internet Archive (also known as “the Wayback Machine”), making them more likely to survive the inevitable change of links that happens as websites are revamped over time. Even better would be including search for other resources as an element of the assignments within the lessons themselves.

Conclusion

When planning a technology project, it is easy to get caught up just in the first round of creating the content, but with a bit of planning and some good strategic choices, you can make it more likely that your project will survive over time, which will increase its cost-effectiveness in the long run.

Please visit the new version of our RAILS Project!

Thanks Shannon for this retrospective and futureSpective. So glad to hear RAILs has a v.2.0! I was an enthusiastic user of Multimedia Lesson Builder and Annotator, and thought UW-M’s model of developing course-centric tools for faculty a brilliant undertaking. As much as I like H5P and PressBooks (and the open source movements behind them), I’d readily plunk down $400 again (not sure what that is in 2022 $$) for something that had similar nuance and elegance. Good riddance to Flash, but still suffering saudades for courseware authoring that made mere mortals feel brilliant!

Thanks for your comment, Jeff! I didn’t know that anyone outside of UW had been using those tools but of course it would be you! 🙂

Excellent compilation of things to keep in mind when creating tech-based materials! All to often we expend huge resources of time and effort for a project that becomes obsolete due to a lack of planning for longevity. This checklist of things to consider will be VERY useful!

Thank you very much for sharing your experience with RAILS!

Edo

Thanks Edo!