Zooming in on Machine Translation Use in L2 Online Classes: Reflecting on the Future of L2 Writing

By Lisa Merschel and Joan Munné, Duke University

DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.69732/JARW7014

How are students using translators in online learning contexts? In the March and June 2020 issues of FLTMAG, Faber and Turrero-García (2020) and Henshaw (2020) articulated pedagogical implications and perceptions among instructors on the use of machine translation (MT) tools such as Google Translate. As learning has shifted in the last two years, moving back and forth from in-person to remote contexts, we were curious to see if students’ use of translation tools changed as well. Our guiding questions were:

- How are students using MT in synchronous online contexts?

- To what degree does MT use differ given the stakes of the assignment (graded vs. ungraded)?

To answer these questions, in Fall 2020 we conducted an anonymous Qualtrics survey of Spanish language undergraduate students at Duke University to inquire into their MT practices that occurred during synchronous Zoom classes. We found that 92% of respondents had used MT to support their language learning during the semester. Our study shows that students used translators in contexts that ranged from on-demand, ungraded writing assignments to graded speaking tasks, but MT was used more frequently in graded tasks.

Background

Our interest in machine translation goes back more than a decade when we first noticed a shift in how students approached writing assignments involving translation tools. Our curiosity drove us to research this further, resulting in a multi-perspective study, Clifford et al. (2013). As instructors and students in all educational contexts across the country transitioned to online learning in March 2020, we scrolled through social media messages from educators in online forums devoted to remote language learning. As we read through comments on ACTFL Central (a platform associated with the American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages) and other online venues, more and more questions and observations related to MT arose from language faculty who expressed an overall sense of frustration with its use by students in their remote classes. These frustrations led us to delve deeper into the issue, and we wondered to what extent our own students were using translation tools during their online courses.

The Present Study

There is a vast literature discussing how, why, and how frequently students use machine translation in asynchronous learning, such as out-of-class writing assignments (Jolley & Maimone, 2022). To better understand student engagement with translation tools in synchronous sessions, the present study surveyed 82 undergraduate Spanish language students, including students at the elementary level (N = 32), at the intermediate level (N = 22); and at the advanced level (N = 28). The survey (IRB protocol 2022-0241) asked students how they were using translation tools in their online classes in a variety of contexts involving on-demand, ungraded, writing tasks, as well as speaking tasks (both graded and ungraded).

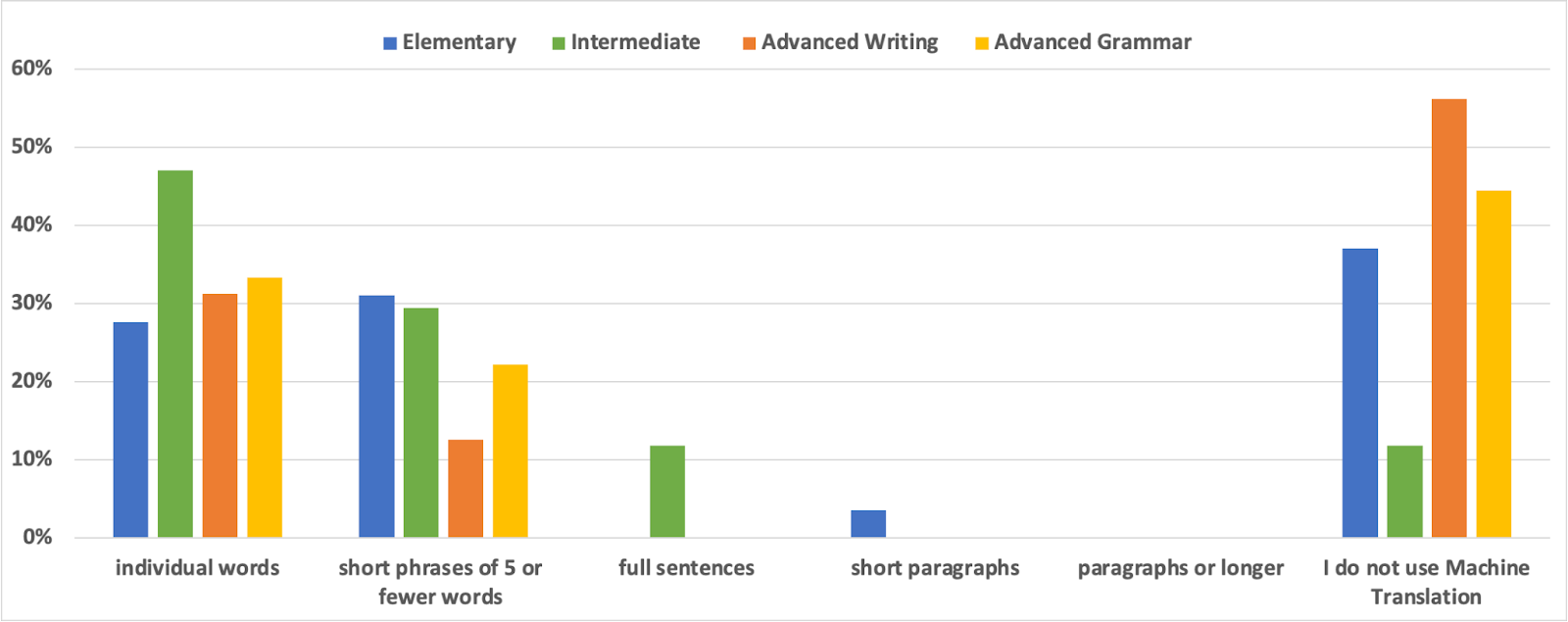

For on-demand, ungraded writing tasks during a Zoom class (collaborating on a Google doc, writing in chat, annotating in Zoom), we found that 50% of students in elementary, 55.5% in intermediate, 17.6% in advanced writing, and 55.5% in advanced grammar classes, translated short phrases of five or fewer words from English to Spanish. The translation of individual words from English to Spanish was less frequent in most levels (26.6% in elementary; 27.7% in intermediate; and 44.4% in advanced grammar), but more frequent (58.8%) in advanced writing. Some elementary and intermediate level students chose to translate full sentences (6.6% of elementary students, 5.5% of intermediate students, but no advanced students).

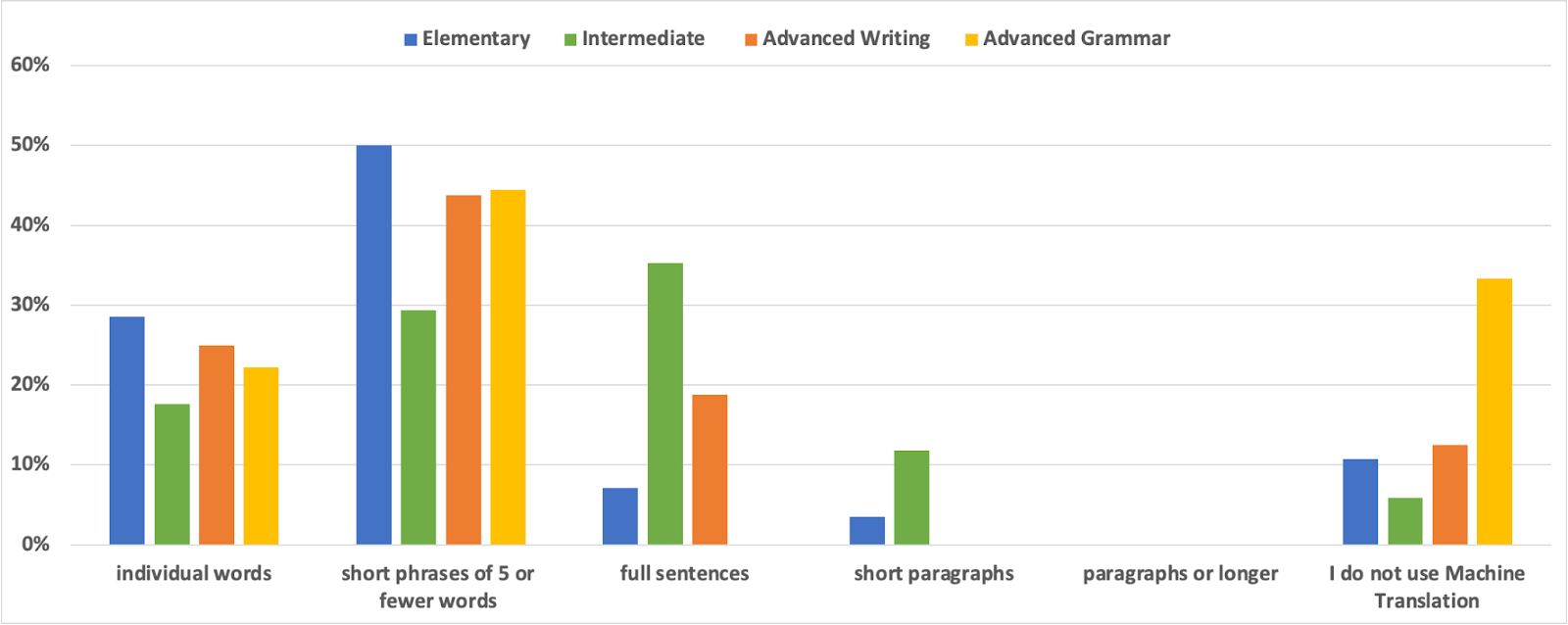

Moving away from writing assignments, for speaking tasks students reported more reliance on translation tools when preparing a graded speaking task (vs. an ungraded one). What particularly stands out is the increased amount of text translated in the short phrases and full sentences categories when the stakes were higher, especially at the intermediate level.

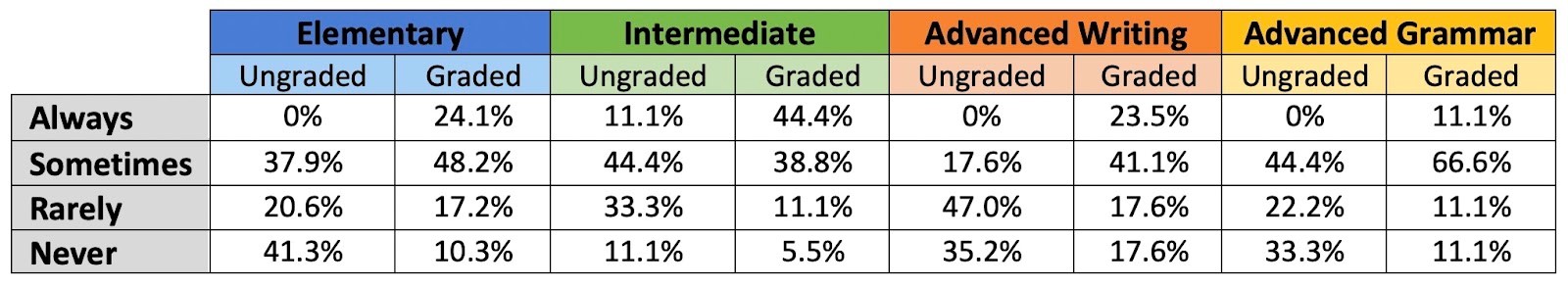

Next, we asked how frequently students used Machine Translation in ungraded vs. graded speaking tasks. Students again indicated more reliance on MT in graded tasks, in line with O’Neill (2019), who found that the percentage of students using MT was higher for graded work (Jolley & Maimone, 2022, p. 29). In our study, the percentages of students who reported using MT for speaking increased when the task was graded, when the always selection starts to emerge more strongly in the data (see Picture 3 below). The notable reliance on MT at the intermediate level may be due to various factors, such as students having to create longer and more complex texts as they move past basic vocabulary and grammatical structures.

Student responses to open-ended questions offer additional insight into the use of translation tools during synchronous online courses. To the question “How has your use of Machine Translation changed this semester given that your Spanish class is now conducted entirely online? Do you think that overall this change has helped or hindered your language learning?” responses at the elementary and intermediate levels indicate greater use of MT tools in their online classes. Students used MT in ways documented in other studies: mainly as a dictionary and to double-check their work. In online learning, students said that MT was useful in breakout rooms if no one knew how to say something (and the professor was not there to ask). It is interesting to read about students who were grateful to be able to use MT “without being seen or judged,” as one student wrote, or to quickly look up a word and regroup to move on with the class (when they wouldn’t be allowed to do so in person). A student in an advanced grammar class noted, “I have had a tab open for words that I do not know. It has helped because a quick translation of the word can be the difference between understanding the teacher and getting lost.” The open-ended responses show that students believed that MT helped their online language learning, although one advanced student commented, “I don’t think that my use of MT has changed. I have always been wary of machine translation anyways, because my teachers have told me it often produces errors, making it obvious that it was used.”

Is Training Students the Answer?

Our study substantiates the assumption among teachers that students heavily relied on computer-mediated tools in their online classes. So where do we go from here? Several recent studies (Ducar & Schocket, 2018; Faber & Turrero-García, 2020; Merschel & Munné, 2022; O’Neill, 2019) suggest that incorporating lessons on MT could benefit students. Jolley and Maimone (2022) point out:

More research is needed to help instructors identify exactly what training of this type should entail to best assist them in making decisions about materials design, course policies, and grading and how such training might help learners make decisions about their learning process. (40)

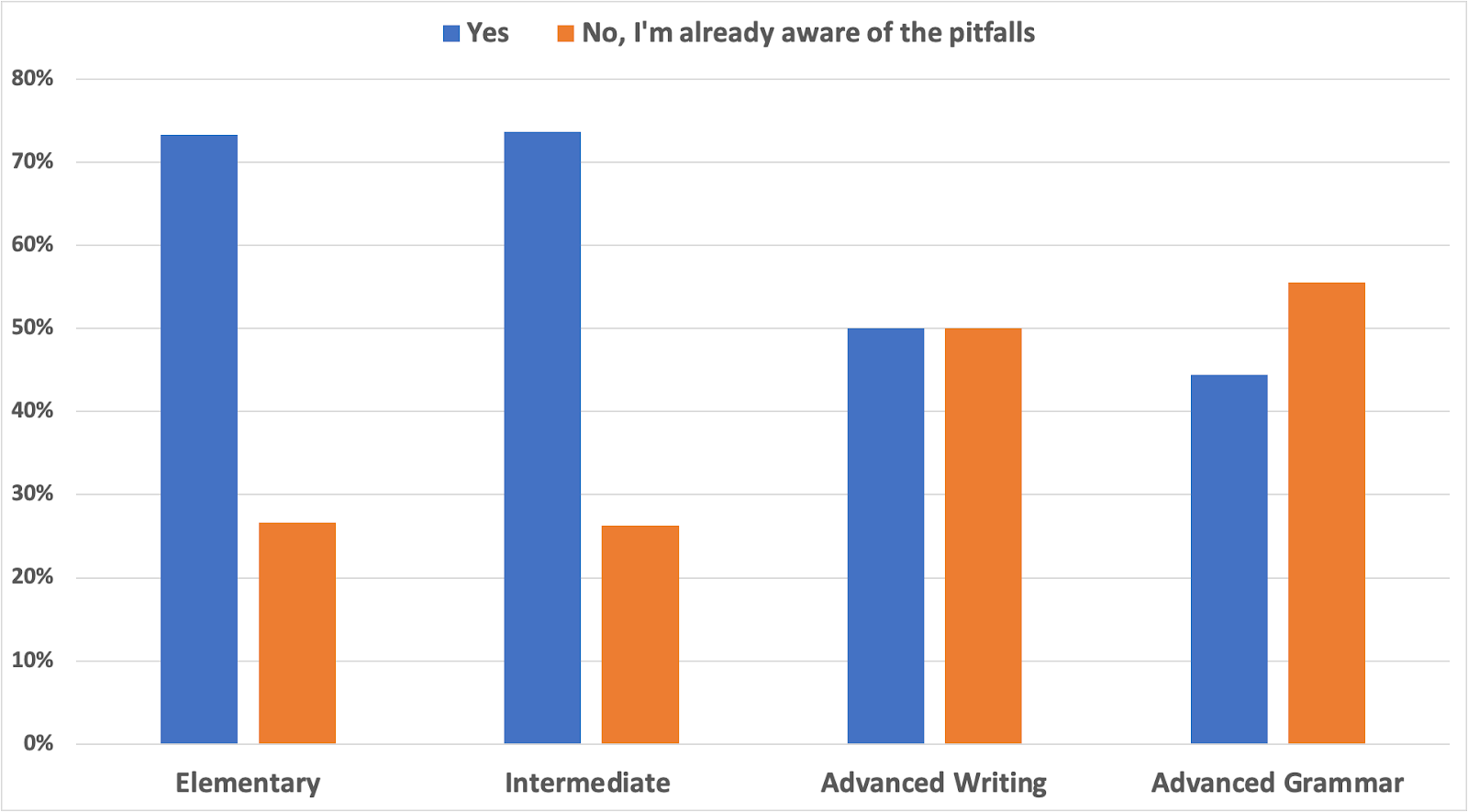

To gauge student interest, we asked if they would be interested in such a lesson.

It is curious to see that students in advanced classes chose in greater percentages the option, “No, I am already aware of the pitfalls,” perhaps suggesting that their understanding of what MT is, and is not, has been already well-established by the advanced level. In contrast, elementary and intermediate level students seem more open to mentoring on this point. Henshaw (2022) presents a counterargument, noting that while training in machine translation may be helpful, it remains unclear if it is useful in second language development. Henshaw brings in a useful analogy, that while Google Translate is like a self-driving car, which can get you where you need to go even if you don’t know how to drive, WordReference, a tool that Henshaw does allow in her class, is like a GPS, which will orient you, but not drive the car for you.

To follow up on this question, we asked “which strategies” students would find most beneficial in such a lesson, and the answers show a possible front for further research. Students indicated interest in comparing what MT produces to what a native speaker would produce. They were curious to compare what MT produces versus what a language learner would typically produce for their level. And they would like to see contexts where MT comes up with inaccuracies. The one student who answered “Other” suggested, “When it is okay to use or beneficial.” Of note, this comment was from a Spanish 101 student, someone who would carry this lesson through the rest of their language classes.

Students and educators crave mentoring and guidance on MT. Recent studies show that educators are starting to move beyond the prohibition of machine translation tools and integrate them into their curriculum (Vinall & Hellmich, 2022b). In a special issue dedicated to machine translation, Vinall and Hellmich (2022a) write about the “translational turn,” a world of language education that is “intimately and undeniably implicated in the presence, use, and development of machine translation software” (p. 5). In the survey we administered, one student expressed enthusiasm about learning more about MT:

[MT] has helped so much! If there is a phrase on the slide or a sentence said during class that I didn’t understand I could use MT to comprehend it as opposed to in-person where I would be too shy to ask for clarification and simply have to accept that I won’t know what it means. But again, I can’t emphasize enough MT is invaluable when used correctly. Merely translating and moving on is useless, but meaningfully translating and taking the extra time to really analyze the how and why of the translation helps with language acquisition immensely.

This student’s view would support an “Integrate-educate” model over a punitive “detect-react-prevent” model of machine translation, as described by Jolley and Maimone. The student’s observation mirrors what others noted in the survey: translation tools are venues for exploration, growth, and further understanding. And yet, if students believe that MT is hindering their language learning (as some commented), but use it anyway, then at the very least, we can intervene and help mediate their interaction with it.

Limitations and Pedagogical Implications

This study has three limitations. First, we were relying on self-reported data and thus had to take the students’ recollection of their MT use at face value. Second, we were unsure as to how instructors addressed MT use in their classes. Third, we had (and continue to have) a policy in syllabi, “In my written assignments, I will not use any computer software that compromises my learning process. This includes translation programs,” which may have inhibited disclosure of students’ MT use.

How should we broach this subject with our students? This is where the rubber meets the road (no, not literally Google) and where there is intense debate and frustration over computer-mediated communication. As mentioned above, we have a policy that prohibits MT use, but the enforcement of this policy has been uneven at best, especially in the last two years as our attention has been focused on pandemic teaching and learning. The takeaway from our study is that students used translation tools, despite their prohibition, in remote learning contexts for ungraded and graded assignments. They used MT for interpersonal, interpretive, and presentational assignments involving speaking, reading, and writing. They used these tools for various reasons, including clarification, double-checking, keeping up with the class, and translating longer texts when preparing graded work. Finally, students indicated they would like to learn more about MT.

Widening the lens from remote contexts to all contexts in which MT may be used, let us look at some of the most pressing MT-related topics at hand. As lifelong language learners ourselves, educators play an important role in defining the future role of MT technologies. How do we ourselves use the technology? How can we involve students in collaboration and research on the topic? How can we welcome students into the practice of inquiry, establishing common ground as we learn more? Reminding students that we are ourselves life-long learners, growing and learning about emergent technologies as they affect not only L2 practices, but our lives as humans in this day and age, is vital as students understand themselves as agents of learning and growth.

As we all know in reading news headlines about developments in AI, Google Translate as an app on the phone or as a browser extension is, really, just the tip of the iceberg when looking at artificial intelligence as a whole. AI developments such as CILLE (Cognitive Immersive Language Learning Environment), in which an AI “agent” can hear, see, and understand its users and engage with students in conversations, are here (Divekar et al., 2021). AI-writing tools such as Jasper.ai can prepare highly-accurate, plagiarism-free text with minimal input from the user. Try Googling “AI writing tools” and see the number of “Best AI Writing Tools” lists. For now, these are mostly paid sites, and mostly English only, but this is only the dawn of AI, and the sun is rising. In May 2022, Google hinted that they are developing eyeglasses that translate languages in real-time. The user wearing the glasses talks with someone speaking a different language and sees the spoken words in their own language at eye-level, providing “subtitles for the world” (Ulanoff, 2022).

To avoid being overrun by advances in new, disruptive technologies, Urlaub and Dessein (2022) urge the world languages profession to “engage in a robust and open debate on the future of the field in an age of artificial intelligence” and argue that the “integration of online translators into the learning environment must happen intentionally and strategically. It should not “just happen.’” Further, they advocate that professional organizations “formulate new learning outcomes for MT-enhanced classrooms.” Building on this notion, we advocate for an ACTFL position statement on digital literacies that guides educators to a practical approach to the use of MT, one that enhances and elaborates on the existing position statement on the Role of Educators in Technology-Enhanced Language Learning. This statement could be updated more frequently (last updated in 2017) to keep up with the “profound shift” as we move from traditional notions of literacies to digital literacies (Elola & Oskoz, 2017, p. 52-53).

A Call for Collaboration

Any discussion about computer-mediated communication invariably brings up the issue of writing, which we touched on only briefly here in this article, since that modality’s intersection with MT is the most widely understood, studied, and observed. We are “living in an exciting time for L2 writing curriculum,” argue Elola and Oskoz (2017), who urge a questioning and redefining of L2 writing practices that reflects our times. As such, they call for a “21st-century reevaluation of literacy, writing genres, and associated instructional practices in the L2 classroom” (p. 58). We are indeed living in an exciting time. Still, this excitement is inextricably intertwined with anxiety about how technologies make their way into, disrupt, and alter how we learn languages. More worrisome still would be any initiatives put forth by policy-makers and administrators to reduce language acquisition to its grammatical, Googleable components, devoid of context, empathy, and nuance.

The pandemic has underscored the many benefits, pitfalls, and inevitabilities of technology-mediated communication. As Klekovkina and Denié-Higney (2022) explain:

It is true that we were able to ‘meet’ our students via screens, but the magic – the human interactions that happen in a classroom – was hardly there. If we want our students to learn the mystery of a new language and reclaim their agency without depending on a machine, we must establish an open communication and honest collaboration between the agents who give language its soul: students and instructors, aka human beings. (p. 119)

As we look to forge new collaborations, now is an opportunity to meet the challenge of MT head-on, in community with each other as students, teachers, and administrators before we are overrun by even more developments in AI. Let’s gather together in the spirit of collective inquiry. One way to begin is to check out Translating Google Translate: Instructional Strategies for Machine Translation in the Language Classroom, a website project developed by Vinall and Hellmich that brings together research, instructional strategies, and resources on the topic. Another way, if you are teaching in higher education, is an invitation to share your thoughts, frustrations, and successes regarding L2 writing. If you are interested in participating, we invite you to click on this Google Form to begin. We will present our findings at ACTFL in Boston.

The “power of yet” (I can’t do this yet) may be frustrating to perfectionist, risk-averse students. Still, students need to be reminded that language acquisition is a slow process that involves trial and error. A growth mindset, coupled with meta-cognitive tasks such as learning about learning, are powerful ways of encouraging language learning that move beyond the uninformed consumerism of machine translation. But at the same time, digital literacy must be developed and promoted among students to equip them with the tools (Google Translate included, we would argue) to understand better, interact with, and grapple with new, almost ubiquitous technologies that are affecting language acquisition, for better or for worse.

All of this is “food for thought,” which, although still incorrect in Google Translate (Henshaw, 2020), is correct, at least in Spanish, in DeepL, which currently claims to be the “world’s most accurate and nuanced machine translation.”

References

Clifford, J., Merschel, L., & Munné, J. (2013). Surveying the landscape: What is the role of machine translation in language learning? @ tic. revista d’innovació educativa, (10), 108-121. https://doi.org/10.7203/attic.10.2228

Divekar, R. R., Drozdal, J., Chabot, S., Zhou, Y., Su, H., Chen, Y., Zhu, H., Hendler, J. A., & Braasch, J. (2021). Foreign language acquisition via artificial intelligence and extended reality: Design and evaluation. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2021.1879162

Ducar, C., & Schocket, D. H. (2018). Machine translation and the L2 classroom: Pedagogical solutions for making peace with Google translate. Foreign Language Annals, 51(4), 779-795. https://doi.org/10.1111/flan.12366

Elola, I., & Oskoz, A. (2017). Writing with 21st century social tools in the L2 classroom: New literacies, genres, and writing practices. Journal of Second Language Writing, 36, 52-60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2017.04.002

Faber, A., & Turrero-García, M. (2020). Online translators as a pedagogical tool. The FLTMAG. https://fltmag.com/online-translators-as-a-pedagogical-tool/

Henshaw, F. (2020) Online translators in language classes: Pedagogical and practical considerations. The FLTMAG. https://fltmag.com/online-translators-pedagogical-practical-considerations/

Henshaw, F. (Host). (2022, Feb. 13). Training students to use online translators and dictionaries: The impact on second language writing scores. (No. 6) [Audio podcast episode]. In Unpacking (SLA) articles. https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/unpacking-sla-articles-episode-6-training-students/id1592888727?i=1000550954373

Jolley, J. R., & Maimone, L. (2022). Thirty years of machine translation in language teaching and learning: a review of the literature. L2 Journal, 14(1). https://doi.org/10.5070/L214151760

Klekovkina, V., & Denié-Higney, L. (2022). Machine translation: friend of foe in the language classroom? L2 Journal, 14(1). https://doi.org/10.5070/L214151723

Merschel, L. & Munné, J. (2022). Perceptions and practices of machine translation among 6th-12th grade world language teachers. L2 Journal, 14(1). https://doi.org/10.5070/L214154165

O’Neill, E. M. (2019). Training students to use online translators and dictionaries: The impact on second language writing scores. International Journal of Research, 8(2), 47-65. https://doi.org/10.5861/ijrsll.2019.4002

Ulanoff, L. (2022). Google blows our minds at I/O with live-translation glasses. Tech Radar. https://www.techradar.com/news/google-blows-our-minds-with-live-translation-glasses

Urlaub, P. & Dessein, E. (2022, March 4). From Disrupted Classrooms to Human-Machine Collaboration? The Pocket Calculator, Google Translate, and the Future of Language Education. [Conference presentation]. Translating Google Translate into Classroom Practices. Berkeley, CA, United States.

Vinall, K., & Hellmich, E. (2022a). Do you speak translate?: Reflections on the nature and role of translation. L2 Journal 14(1), 4-25. https://doi.org/10.5070/L214156150

Vinall, K., & Hellmich, E. (Eds.). (2022b). Machine translation & language education: Implications for theory, research, & practice. L2 Journal, 14(1). https://escholarship.org/uc/uccllt_l2/14/1

New machine translation opportunities are perfect for corporations and businesses looking for translation assistance. Thanks for sharing!