Interpersonal Communication in the Remote Classroom: Maximizing the Use of Breakout Rooms

By Elena Lanza and Reyes Morán, Northwestern University

DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.69732/WFOP6602

The year 2020 marked the beginning of a new era for both students and educators when, in a mad panic, institutions scrambled to make the shift from face-to-face (F2F) to online instruction. After the initial shock and subsequent adjustment, remote teaching and learning became the new reality for much of the educational systems worldwide during the worst of the COVID-19 pandemic. But even as we emerge from the pandemic, fully online or hybrid instruction will remain relevant for the foreseeable future, whether as the new default, or as a complement to F2F instruction.

The online pivot in the K-12 educational system and in higher education was mostly managed via videoconferencing platforms such as Zoom or Microsoft Teams, and there was rapid innovation in using existing tools within these platforms to enhance student engagement. Certainly, these videoconferencing tools helped educators solve the initial crisis by providing a remote environment that could replicate the in-person classroom setting, albeit with certain expected limitations. However, a central concern for all educators during this shift was how to maintain student engagement during synchronous online sessions, and this was of particular relevance for those teaching languages, where small-group interaction is critical to increase learners’ oral proficiency. One of the most powerful virtual tools for replicating peer-to-peer and small-group discussions were breakout rooms (BRs), where the instructor could easily assign, monitor, communicate, and directly engage with small student groups in a whole variety of ways.

In this article we will present an overview of how we translated the methodological framework that we use for target language (L2) instruction at our home institution to an online environment, and we will focus on the lessons learned in using BRs to facilitate small-group interaction in order to enable learners’ oral proficiency within the L2 online environment. While our use of BRs was specific to our student population and methodological framework, the strategies we discuss could be applied to any L2 learning context (at all levels of proficiency) and/or to any academic discipline.

General Methodological Framework for F2F or Remote L2 Teaching

The field of second language acquisition is a vast and dynamic discipline in which research-based and practice-based approaches coexist, enriching and complementing each other in diverse ways. It is in this context that, in our experience, a combination of the flipped model and content-based instruction (CBI) has been a useful formula to achieve the set learning objectives in our courses for the three modes of communication, as outlined in the ACTFL Performance Descriptors. Furthermore, it has proven to be a powerful approach to stimulate and strengthen the interpersonal mode, whether in a F2F or in an online setting.

In world language instruction, the flipped approach was certainly not a new concept when the pandemic hit and forced us all to find alternative teaching mediums, but for many the flipped approach took on an even more central role. Many educators unfamiliar with the flipped model prior to having to teach online (and hence being forced to rethink their course components and how they would be laid out), found in the flipped model a reliable ally. Robert Talbert is one of the leading experts on this model, in particular when implemented in higher education; and he defines flipped learning as “a pedagogical approach in which first contact with new concepts moves from the group learning space to the individual learning space in the form of structured activity, and the resulting group space is transformed into a dynamic, interactive learning environment where the educator guides students as they apply concepts and engage creatively in the subject matter” (Talbert, 2017). In the language classroom, the main focus should be placed, precisely, on this interactive component in order to maximize the more reduced (and therefore, more valuable) contact hours with our students.

On the other hand, CBI has also been a well-accepted and widely implemented methodology since the late 1980s and is an effective approach to create an immersion-like environment to help L2 learners to purposefully and meaningfully use the target language. Content-based approaches “…view the target language largely as the vehicle through which subject matter content is learned rather than as the immediate object of study” (Brinton et al., 1989, p. 5). Moreover, CBI integrates “more challenging themes (e.g. environmental issues, bullying, discrimination) not only to enrich classroom discussions but also to make connections to the ‘real world’ while developing students’ advanced thinking and literacy skills” (Lyster, 2017, p. 2). CBI also allows L2 learners to independently acquire the target language beyond the classroom setting, fully aligning (and “closing the circle”, so to speak) with the flipped model. In a study conducted amongst L2 learners of Korean, Kim et al. (2017) concluded that the effects of the flipped classroom in the L2 learner’s cognitive processing are positive when combined with content-based language teaching. Furthermore, the 2007 MLA report “Foreign Languages and Higher Education: Structures for a Changed World,” emphasized CBI’s relevance in the context of the traditionally polarized academic departments with language programs on one hand (“little to no content” and focus on form) and, on the other, literature tracks (“only content” and no focus on form), and recommended the establishment of a continuum that would connect the teaching and learning of form and content through all levels of proficiency.

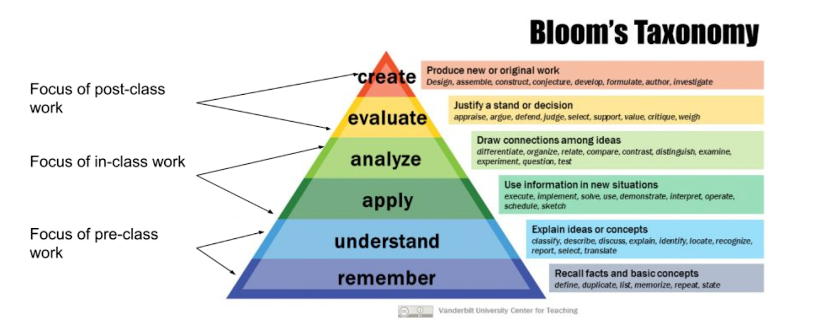

To complete this methodological framework,we incorporate Bloom’s Taxonomy (through backwards design) as a third guiding element for instructors. The taxonomy (Bloom, 1956) and its subsequent revisions (Anderson and Krathwohl, 2001) categorized six distinctive but interconnected cognitive abilities that helped educators delineate learning outcomes for their courses. These abilities progress from simple to more complex, building upon each other. In the flipped model, these categories are also “flipped” (Talbert, 2021) in order to maximize the valuable F2F time spent together by the instructor and the students (Picture 1). The instructor should decide what is the most valuable aspect about that in-person interaction. To that effect, Talbert proposes that the less cognitively demanding categories of the taxonomy (remember and understand) could be part of preparatory assignments, whereas the more cognitively complex categories (apply and analyze) would be implemented in class; lastly, the most complex categories (evaluate and create) could be assigned, according to Talbert, as post-class work. We also argue in this case that they could also be implemented while in class, depending on the objectives for that individual session:

With this in mind, instructors would be able to facilitate and maximize the valuable F2F time (both in person and remotely), and to determine whether students achieve the class objectives in a fully learner-centered setting.

In the next sections, we will outline some important challenges associated with the implementation of a flipped (and learner-centered) approach in the remote environment and how we overcame them by using BRs to foster student engagement and interpersonal communication in all our classes.

Classroom Management in F2F vs Remote Learning Environments

BRs may be at a somewhat disadvantage when compared to F2F settings when it comes to general classroom management and interaction for teachers and students. The following table (Table 1) outlines key classroom management elements and their presence (✓) or absence (X) in a F2F setting vs in a BR both from the teacher and the student perspectives:

| CLASSROOM MANAGEMENT ELEMENTS | F2F | BRs | |

TEACHER |

Time control for task completion

Communication with students (clarity of instructions, asking questions, etc.) Feedback for the class General grasp of group dynamics (engagement, distractions, etc.) |

✓

✓ ✓ ✓ |

X

✓ ✓ X |

| STUDENT | Time control for task completion

Presence (camera on vs. off, muted microphone, connectivity issues, etc.) Engagement (silences, distractions,etc.) Visual cues (body language, facial expressions, etc.) Immediate access to instructor |

✓

✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ |

X

X X X X |

Table 1 – Classroom management elements F2F vs. BRs

As we can see, most of the elements that are typically more difficult in a remote synchronous environment are related to student engagement and how to deal with the lack thereof once students go to BRs. Some of these issues are beyond the instructor’s control in the online environment, such as the drastic reduction or disappearance of visual cues in non-verbal communication, or the presence of potential distractions for the student(s); in the end, we may need to come to terms with the fact that there is nothing that can be done regarding some of these issues and may need to plan around them. The flipped classroom, however, can help alleviate and even improve many of the other listed elements such as student engagement, immediate access to instructor’s feedback, or general grasp on the part of the instructor of what is happening at any given moment while in class.

Fostering Learner Engagement in BRs

As mentioned previously, when considering what activities to implement in a L2 class, the focus should remain on the learner’s needs and on providing the maximum amount of opportunities for oral output production at the target level of proficiency. When using BRs, we should be able to recreate for the most part those same opportunities, with activities that are anchored on meaning, communicative and goal-oriented, authentic and grounded in real-life topics and experiences, while encouraging analysis and reflection, and fostering collaboration and interaction amongst our students (González-Lloret, 2020).

Many of the activities and sequences presented in Table 2 can be easily mixed and matched, but they all share the same objective: to anchor the time spent in a BR and during the report back in a meaningful way for all stakeholders, based on the work that the student has done in preparation for the class, consistent with the flipped model. While in class, students will be at the center of the learning process, providing the majority of the content and asking each other questions to clarify or expand on the topic at hand. In this context, the instructor will act as a facilitator or guide, and not as the main source of “knowledge”:

| Preparation (pre-class) | BRs (in class) | Report back (in class) |

| Watch a lecture

Students watch or listen to a pre-recorded lecture.

|

Guided discussion

Students discuss the lecture previously watched using an outline provided by the instructor. |

Analytical report

Students share main points to remember; different groups provide points for different parts. |

| Research a topic

Students research a previously assigned topic and prepare a presentation on it and/or questions for their classmates. |

Jigsaw activity

Students complete an information gap activity with the different information provided by their classmates. |

Question-based discussion

Students bring back to the main room a set of 2-3 questions to be discussed as a closing activity. |

| Work on a case study

Students examine a case in a real-life context with a certain level of detail. |

Create a plan of action

Students create a plan in order to solve challenges posed by the case study. |

Peer feedback

Students provide feedback to the other groups based on the proposed plans. |

| Read written texts

Students read articles, blogs, literary texts, etc., complete comprehension questions, and/or prepare new questions to be discussed in the next class. |

Informal conversation

Students discuss the topics presented on the readings using the guiding questions that they prepared previously. |

Share findings to apply principles

Students find common threads or examples to apply key concepts to the newly-learned material. |

| Creation of a questionnaire

Students create a survey, poll, questionnaire, etc. to be conducted in the next class. |

Conduct a survey

Students use the questions previously prepared to conduct a survey and gather data. |

Share takeaways

Students compare their answers to those of their classmates. |

| Watch a film/documentary

Students watch audiovisual materials that may be longer than a few minutes. |

Discuss film/documentary

Students discuss or debate topics from the film/documentary. |

Round table

Students take turns to share the main takeaways after their discussion in BRs. Others (dis)agree with those conclusions. |

| Complete a worksheet

Students complete worksheets focused on form, with more mechanical / drill-type activities. |

Peer review

Students help classmates solve questions, in a tutorial-type activity, based on a worksheet completed previously. |

Q&A session and feedback

Students ask questions to the instructor and take this opportunity to clarify aspects that still need more explanation. |

Table 2 – Sample activity sequencing for a flipped L2 class in BRs

The following is an example of how to apply these strategies to a lesson plan:

Example 1: Creating an ideological map of Latin America through its presidents (50 min session)

RESEARCH ACTIVITY: Pre-class, individual students are assigned a Latin American president and they have to prepare a 5-min presentation including biographical information, political party and ideology, main challenges while in office

JIGSAW ACTIVITY: In class, in BRs, in groups of 3 for 15-20 mins, students will present the information about their president. After listening to the presentations, students will come up with two questions such as: “Is there a main ideology in Latin America?” or “Does the US have the same challenges as some Latin American countries?”

QUESTION-BASED DISCUSSION: In the report back, the whole class will complete an ideological map of Latin America with all the information gathered (5 mins) and subsequently they will engage in conversation addressing the questions they prepared in BRs (15-20 mins).

Also noteworthy is the fact that the report back should not be a summary of what they already did, but rather it should provide an opportunity for students to build up and expand on what other groups are sharing. As we saw in Example 1, during the report back portion of the class, students do not simply relay to the rest of the classmates what they just discussed; instead they bring new questions to address more analytical and complex tasks such as comparing and contrasting political systems and/or come up with main takeaways regarding Latin American politics today. This workflow allows the instructor to provide feedback if deemed necessary, and helps them assess what should be reviewed or reinforced in the next class session.

Instructor Management of BRs

Another important aspect to help instructors facilitate the work of learners while in BRs is the establishment of clear and consistent protocols before, during, and after students interact in them. These protocols are based on our own trainings and experience as instructors, as well as valuable student feedback:

Before sending learners to BRs:

- Provide clear instructions before each task, and explain the learning objectives established for it: What is the purpose of this activity and why is it important?

- Share instructions with students before sending them to BRs: Google Docs is a great ally since Word documents or Power Points shared via chat sometimes do not download on time (or at all); other times, students are unable to open those files on their computers due to technical issues (may not have the proper software installed, may experience connectivity issues, etc.).

- Set a time and stick to it and let them know when you will disconnect the BRs: how much time students will spend in a BR will depend on the activity at hand; in language classes, for instance, 5-10 mins working on the same task and with the same classmates are typically sufficient to complete a targeted activity.

- Keep groups small: a team of 2-3 students is an ideal number in a BR; more than that and there is a very high probability that a few of them will disengage and/or get off topic.

- Communication with students is key, since this is one of the main drawbacks of BRs: Encourage them to use the “Call for help” button if questions come up, or allow them to return to the main room on an as-needed basis; this will avoid awkward silences or going off topic while they are waiting to be back in the main room. Another useful idea is to run a “mock” BR in the first week of class so that students become familiar with the instructor’s expectations for the BRs immediately.

Finally, let them know when you will enter the BRs (if at all). Students, for the most part, get distracted or self-conscious when the instructor suddenly shows up while they are in the middle of a discussion. Just knowing that the instructor may randomly appear gives them a fair warning and reduces the surprise factor, better preparing them for it.

While learners are working in BRs:

- Use the “Broadcast Message to All” button to send quick reminders or clarifications; however, be selective with the amount of messages sent since they can also be distracting.

- Send a 1-2 min warning before disconnecting the BRs.

When entering BRs:

- Wait a couple of minutes until they have established a steady work pace.

- Keep your microphone muted and your camera on: it is a less intrusive approach since learners are not expecting you to say anything, while at the same time, it maintains a certain level of personal interaction since they can see your facial expressions.

- Do not interrupt the conversation or distract them – observe and leave quickly if there are no questions or once you make sure they are on track.

- Keep visits short, to less than one minute if possible.

Once the activity is completed and BRs have been disconnected, it is time to return to the main room. The report back with the whole class is as relevant as the work done in BRs. Learners often remark that it is common to have to summarize what they discussed in BRs in this portion of the class. Not surprisingly, they see this class component as redundant and not particularly engaging.

The Learner’s Perspective on BRs

In winter quarter 2021, we conducted informal anonymous surveys amongst our students in the courses Spanish 199: Contemporary Spain (Intermediate-Mid/High level of proficiency) and Spanish 201: Conversation on Human Rights Latin America (Intermediate-High/ Advanced-Low level of proficiency) to gather information about the effectiveness of BRs in replicating the pair/group work in these content-based language courses. Students completed the survey on a voluntary basis, and we received a total of 53 answers. Almost 55% of the students indicated that BRs were highly effective in replicating interpersonal interaction, 45% considered them to be effective sometimes, and 0% indicated that they were not effective.

The other major question was whether they thought that all students participated equally while in BRs: 24.5% indicated that students were equally engaged; 70% of the students answered that some students are more engaged than others; and 5% indicated that students were disengaged. Students also acknowledged that when coming to class prepared, the interpersonal communication in BRs was significantly more productive; in contrast, those who did not do the preparatory work were typically silent or disengaged in these cases. Therefore, creating follow-up prompts where learners have to build up on what other groups presented, for instance, or refute arguments from others, seemed to be a more successful way to keep them motivated and involved while being out of the instructor’s sight in BRs. The following quotes from the survey answers can further illustrate our students’ awareness regarding the importance of the flipped approach:

“In my experience, engagement depends more on if students have done the prep work for the class, rather than the nature of BRs themselves. If students have done the homework, they’re more engaged than those who haven’t.”

“When all of the students completed the materials outside of class breakout rooms are great. Sometimes part of the group didn’t do the reading or whatever other assignment so the BR does not facilitate helpful interaction.”

Final Takeaways

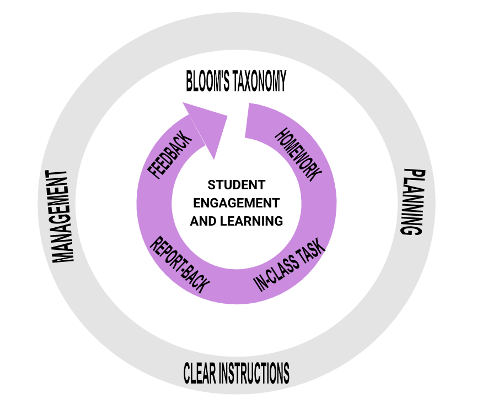

When using backward design to create a lesson plan based on the flipped classroom approach (Picture 2), the time that learners spend in BRs can be engaging and fulfilling. Outsourcing some of Bloom’s categories to the homework assignments will help our students be more confident and ready to share ideas while in class, either diminishing or eliminating the impact of some of the most concerning aspects of synchronous remote teaching (uncomfortable silences, distractions, perceived loss of control on the part of the instructor, etc.). If students know that most of the responsibility to carry the weight of the class session is on them, they will take ownership of the learning process and will be active and willing participants while in class and beyond.

In this context, BRs have become an ally for both the instructor and the learner, facilitating interpersonal communication, collaboration, and the achievement of concrete learning objectives for each class session. Keeping the time in BRs short and varying the groups will also contribute to productive in-class time. With some planning, the instructor will also be able to manage classroom dynamics and make the most out of that F2F time with their students, easily pivoting from a teacher-centered approach to authentic learner-centered instruction.

References

Anderson, L. & Krathwohl, D. (2001). A Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching, and Assessing: A Revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. New York: Longman.

Armstrong, P. (2010). Bloom’s Taxonomy. Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching. Retrieved May 22, 2022, from https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/blooms-taxonomy/

Bloom, B. S. (1956). Taxonomy of Educational Objectives, Handbook I: The Cognitive Domain. New York: David McKay Co Inc.

Brinton, D., Snow, M. A., & Wesche, M. B. (1989). Content-based second language instruction. Boston: Heinle & Heinle Publishers.

González-Lloret, M. (2017). Technology for task-based language teaching & S. Sauro (Eds.), The handbook of technology and second language teaching and learning (1st ed., pp. 234–247). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

González-Lloret, M. (2002). Collaborative tasks for online language teaching. Foreign Language Annals, 53: 260– 269. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/flan.12466

Kim, J.-e., Park, H., Jang, M. & Nam, H. (2017), Exploring Flipped Classroom Effects on Second Language Learners’ Cognitive Processing. Foreign Language Annals, 50: 260-284.https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/flan.12260

Lyster, R. (2017). Content-based language teaching. New York: Routledge.

Lomicka, L, & Lord, G. (2018). Ten Years after the MLA Report: What Has Changed in

Foreign Language Departments?, ADFL Bulletin, Vol. 44, No. 2.

MLA Ad Hoc Committee on Foreign Languages. (2007). Foreign Languages and Higher Education: Structures for a Changed World. Profession. 2007, 234-245.

Talbert, R. N. (2017). Flipped Learning: A Guide for Higher Education Faculty. Stylus Publications.

Talbert, R. N. (2021, June). Seven Steps to Flipped Learning Design: A Workbook. June 2021. Version 5.0., Creative Commons. Retrieved May 25, 2022, from https://rtalbert.org/seven-steps/