Bridging Cultures Across Borders: Intercultural Engagement through a Virtual Collaborative Project

By Silvia Giorgini-Althoen, Wayne State University

Various telecollaboration initiatives have blossomed in recent years, but the pandemic intensified the need to find learning tools to face new challenges and to maintain higher standards of interaction in our language classes. During the spring and summer of 2020, like everyone else, instructors at Wayne State University were redesigning courses to offer more experiential and creative assessments as we shifted our instruction online. Through the initiative I describe below, we discovered how to create dialogue across continents, to increase cultural awareness and competencies, and to give students more agency in their learning – all through the use of technology.

Virtual Exchange Project and Project Goals

Virtual exchange projects are becoming a strong ally in second language education (O’Dowd, 2019). Fortunately, Wayne State University hosted a COIL (Collaborative Online International Learning) workshop in 2019, during which we were exposed to the pedagogy, strategies, and ideas on how to implement this model to our language classes. COIL involves a structured collaboration between faculty and students in various parts of the world through technology, thus enhancing intercultural awareness and competencies. (Appiah-Kubi, 2020).

The sudden switch to online instruction prompted us to consider adopting a similar approach for our classes. This led me to contact my Italian colleague Cristina Gavagnin who teaches at Alpen-Adria University, in Klagenfurt, Austria. I asked her if she was interested in a virtual exchange for an Italian intermediate level class. Fortunately, she accepted enthusiastically. Thus, in the summer of 2020, Cristina and I started to design our project that involved two groups of students of Italian at a similar level of proficiency in the U.S. and in Austria. We decided to adapt the COIL model to our learning outcomes to provide students opportunities to engage with each other, exchange ideas, and share their knowledge (Van Deusen-Scholl, 2014). We planned a virtual exchange that would rely on the use of various types of technology and multimodal activities that provided creative and practical applications to engage and motivate students, thus enhancing their interpretive, communicative, and cultural skills. Integrating this form of “high-impact” and adaptive virtual exchange would provide students a global learning experience even during a global pandemic, without leaving their homes, and/or campuses.

It is important to note that our classes were at a similar linguistic level of proficiency: A1/A2 level (QCER Common European Framework of Reference for Languages)/Novice High/Intermediate Low-Mid (American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages, ACTFL). This was a critical aspect that prompted us to partner, as instructors, to design the project, and the students were partnered by the teachers to complete the planned activities. The goal was to design a project aimed to help students to improve their linguistic skills to the next level, while implementing group collaboration between the American and Austrian students. The fact that we were situated on opposite sides of the world, yet teaching/learning the same language, inspired us to design an experience that invited cultural comparison and intercultural reflections. We designed a pedagogical model to offer a highly interactive, learner-centered environment, based on a mostly asynchronous approach with a few synchronous class-to-class interactions. We saw ourselves working as facilitators, providing guiding questions and technological assistance when needed. Our aim was to improve students’ linguistic skills and global perspective while stimulating their creativity with the use of different technologies, thus exposing them to an intercultural and collaborative opportunity. We designed collaborative speaking and writing tasks aimed to engage students and to motivate them to apply the language skills learned in class.

Technology and Implementation

We were excited by these ideas, but we soon realized that there were some issues we would have to consider. First, we had to deal with institutional differences. We discovered that our institutions had two different academic calendars, and that the Austrian students would start their classes seven weeks after Wayne State. This was resolved by initiating the program halfway through the Wayne State semester, integrating it into the regular planned activities. Second, we had two different LMS (Learning Management System) platforms: Alpen-Adria University uses Moodle, while Wayne State University, Canvas. We were able to use Google Drive as an alternate tool. Last, but not least, a very practical difference — a six-hour time difference. We realized that the best opportunity to overcome this was the integration of multimedia resources that would allow students to communicate, use presentations, make videos, and work in collaborative writing. The students decided on their own to communicate using Whatsapp and Facetime.

We decided to divide the students into six groups with four students each. Grouping students was based on our knowledge of them from previous semesters. Therefore, we tried to match them according to both their level of proficiency and/or interests (when they were known).

The 10 American and 14 Austrian students were thus divided:

- four groups with two American and two Austrian students,

- two groups with one American and three Austrian students.

The project was articulated in stages, each with a specific task. Tasks included individually filming and editing videos about themselves and their daily lives, collaborative writing, editing, and preparing a final cultural presentation. In the syllabus we provided students with a detailed table in which all tasks and deadlines were indicated to help them organize and manage their time for the project. They knew when to post each individual video to share with their group, when to write collaboratively and peer edit the cultural comparison, as well as when to prepare their final presentation.

Students used a Google Drive and shareable folders for each group to upload their shared videos and writing assignments, as illustrated below:

While students uploaded their files in Google Drive, the instructors created groups within their institutional LMS to assess and provide feedback on student progress.

The project was articulated in two major parts: Part 1 focused on speaking, and Part 2 on writing. In Part 1, students worked independently on creating three videos for their group, in which they introduced themselves, described their daily activities, and talked about their cultural interests. In these videos students went beyond our expectations. They demonstrated agency, creativity, and enthusiasm. They went on location and/or used creative editing techniques to present their own cultural and personal reality. Their creativity ran free, and they produced high quality videos in which they not only introduced themselves to their groups but took charge of the task and experimented with cool editing techniques. They truly ran with it!

This picture is an example of the video activity “Introduce your daily routines.”

In this video presentation the student created a very colorful and dynamic show of her daily routines. She used PowerPoint with Gifs, videos, and images for an engaging narration of her daily activities to introduce herself to her group.

In the picture below, you can see an example of how another student went beyond just introducing herself to the group: she decided to proudly share her Filipino heritage by integrating a video of a traditional dance, further highlighting the intercultural facet of this task.

These videos allowed students to engage on a deeper level and to establish a sense of community across borders.

After the students learned about each other’s lives and interests shared in their videos, we began Part 2. Here the students worked collaboratively to write a cultural comparison between Detroit and Klagenfurt in a 3- to 5-page paper. For this part, we guided students with questions to reflect and exchange ideas about cultural and personal events. Just like the videos, the students went beyond our original design and expectations. They included other cultural realities that added further significance to the task.

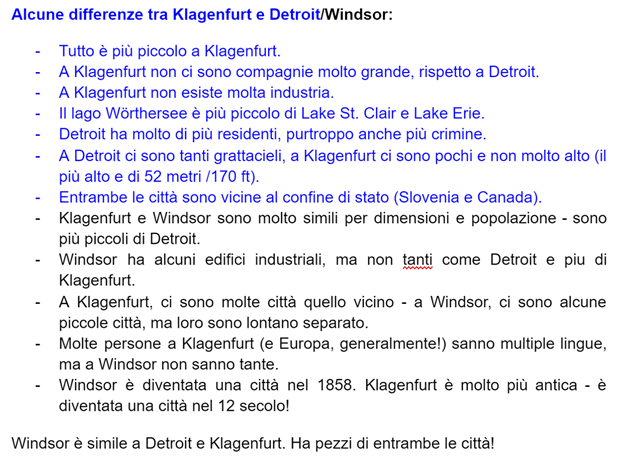

In Picture 4, you can see an example of collaborative writing. The purpose of this task was for students to practice their writing skills while critically thinking about their cities and culture. For this task the instructors provided some guiding questions such as observing American influences in Austria and vice versa, or differences between Klagenfurt and Detroit. We asked them to reflect on stereotypes associated with America and Austria. We also asked them to comment on Italy and Italian culture. Lastly, we wanted them to reflect on how this exchange helped them learn about themselves and their culture.

In the example below, a Canadian and Austrian student described and compared their cities: Klagenfurt (in blue) and Windsor, a small Canadian city across the Detroit River facing downtown Detroit (in black). The Canadian student went beyond what was asked; she extended the comparison to include Windsor and argued that: “Windsor is similar to Detroit and Klagenfurt as it has pieces of both cities” thus adding more cultural breadth to the paper.

In the shareable Google document, we encouraged students to individually color-code their entries to visually indicate not only their contributions to the cultural comparison, but also to provide each other with feedback based on the videos they shared. The various students’ contributions could also be distinguished from each other using the document’s history, in case of accessibility concerns.

This strategy made students accountable for their own contributions to the group’s progress, while also allowing the instructors to follow their participation. The document history showed timeliness in submissions, and the color-coded contributions visually indicated the participation. It is hard to say if this color-coding strategy prevented some students from slacking, but it certainly helped us to get a sense of who was more invested in the success of the project. It also helped us to intervene and encourage more participation from the few who were letting their fellow group members do all the work.

An important part of Part 2 was the peer editing requirement. Students in the same group corrected each others’ writing. Then, when they were satisfied with their paper, each group read and commented on another group’s paper, also adding their suggestions for improvement. The collaborative and peer editing aspects of the project allowed students to engage at a deeper linguistic level, causing them to become more aware of lexical choices and spelling.

It was in this collaborative writing stage of the project that students showed what they could do with the language (and culture) learned so far in their academic career, particularly during this exchange (NCSSFL-ACTFL Can-Do Statements).

Exchange Experience

In line with the AAC&U Value Rubrics (Rhodes, 2010), this collaborative exchange project provided a “global” opportunity to explore, engage, and learn more about (inter)cultural products, practices, and perspectives. The COIL model provided the framework to create a positive environment that promoted the development of intercultural competence skills. The use of technology allowed the connection on two opposite sides of the world, and students were able to explore and discuss the similarities and differences between their realities.

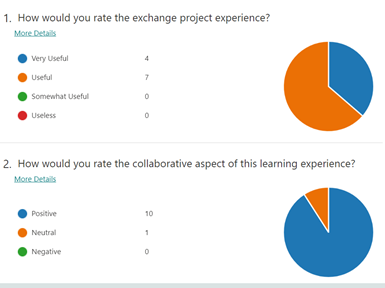

At the end of the project, we asked students to respond to a five-question survey regarding the exchange. Eleven students participated in the survey (46%), and their responses were encouraging and offered valid suggestions for improvement. Overall, students found this project helpful. In addition to improving their Italian, they felt it allowed them to learn about a different country and its culture.

We asked them to rate the exchange project and how they felt about the collaborative aspect of this learning experience. Overall, seven students found the experience useful, and four students rated it as very useful. Ten students confirmed that this collaboration was positive, while one rated it as neutral.

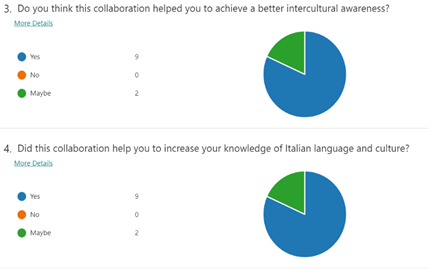

We further asked the participants to reflect on the experience and consider if the collaboration helped them to achieve a better intercultural awareness and if they felt like it helped them improve their language skills. Nine students responded affirmatively, while two were neutral.

Last, we asked them to further reflect and explain how the experience engaged them. All responders underlined how beneficial the experience was in helping them, as one stated, “to think, speak, and communicate in Italian”. Another stated that, even if there were connection or collaboration issues, “in terms of language it did stimulate and engage me”. Another wrote that s/he “enjoyed this (exchange) and learned a lot”. Some American students felt that the Austrian students had a higher level of proficiency, yet, as one stated, “reading and listening to them did help my understanding of sentence structure.” We feel that these final two “verbatim” comments from American students further underline the positive impact of this experience. One student wrote: “I really liked it because I’ve never done something like this before and it was very interesting talking to people from a different country.” Another said: “I was stimulated and engaged because I enjoy learning about other cultures, and sharing my culture with others. I think collaborating with people from different parts of the world and sharing our stories was a really great way to see how people outside of North America live on a day-to-day basis and what their customs are.”

Lessons Learned

We recognize that this was a small pilot project, and the results cannot be generalized. Student responses to the survey indicated some issues we would need to address in future implementations. Even if the feedback was positive overall, we learned some valuable lessons:

- The virtual exchange relied on the use of various types of technology and multimedia activities. A few students told us that they were not comfortable with some of the ‘tools’ they were asked to use. Moving forward we will streamline the process and provide tutorials on each technological ‘tool’ we expect students to use.

- Other practical challenges we encountered, such as the time difference, different academic calendars, and a different pace, created problems with communication and deadlines. These aspects should be addressed more carefully when designing the project stages and deadlines.

- Relying on Google’s tools because of our institutions’ different LMS platforms seemed to make students feel less academically accountable, and some expressed concerns about privacy. This is an important aspect to consider for future exchanges.

- The requirement of making three videos might have been excessive. Students found it cumbersome and time-consuming, as they also had to watch each of their group-members’ videos. In the future, we may just ask for one longer video.

Conclusion

Engaging and challenging students with high-impact activities allows them to demonstrate learning at progressively more sophisticated and complex levels of achievement. These practices are in line with the recommendations of the American Association of Colleges and Universities (AAC&U) for more high-impact practices as tools for effective and transformative teaching and learning experiences (Vahed A., 2020).

Overall, we were pleased with the results. During this exchange we noticed the pedagogical possibilities afforded by the integration of technology, innovative teaching strategies, and cultural opportunities. The project provided students a global learning experience that allowed them to engage, collaborate with peers, practice/improve their language skills, and increase their cultural competencies without leaving their homes/campuses. The technology and multimedia activities in both spoken and written tasks provided creative and practical applications. The collected data indicated that students felt that this experience engaged them and enhanced their interpretive, communicative, and intercultural abilities.

For the students, the ability to “escape the pandemic” was especially welcome. They were able to ‘travel’ across borders virtually, when the world closed for the pandemic, and interact with fellow students and learn about their daily lives. This aspect offered an unexpected positive psychological support. More importantly, students took charge of their learning. They employed a creative approach to technology, using video-editing techniques, and discovered more about their respective cultures. Students told us that this project stimulated their interpretive skills along with increasing their awareness of spoken fluency and accuracy.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank colleague Prof. Cristina Gavagnin for her enthusiasm, friendship, collaboration, and support throughout the project, and Prof. Elena Past of Wayne State University for her steadfast encouragement and constant assistance.

References

Appiah-Kubi, P., & Annan, E. (2020). A Review of a Collaborative Online International Learning. iJEP10 (1), 109-121. https://doi.org/10.3991/ijep.v10i1.11678

Klen-Alves, V., & Tiraboschi, F. F. (2018). Experiencing Teletandem: A collaborative project to encourage students in tandem interactions. Revista do GEL, 15(3), 109-130. https://revistas.gel.org.br/rg/article/view/2416/1457

NCSSFL-ACTFL Can-Do Statements | ACTFL. (n.d.). ACTFL.Org. Retrieved September 19, 2021, from https://www.actfl.org/resources/ncssfl-actfl-can-do-statements

O’Dowd, R., & O’Rourke, B. (2019). New developments in virtual exchange for foreign language education. Language Learning & Technology, 23(3), 1–7. http://hdl.handle.net/10125/44690

Rhodes, T. (2010). Assessing outcomes and improving achievement: Tips and tools for using rubrics. Washington, DC: Association of American Colleges and Universities.

Vahed, A. & Rodriguez K. (2020). Enriching students’ engaged learning experiences through the collaborative online international learning project, Innovations in Education and Teaching International, DOI: 10.1080/14703297.2020.179233

Van Deusen-Scholl, N. (March 2014). The Shared Course Initiative: A Model for Instructional Collaboration Across Institutions. The FLTMAG. https://fltmag.com/the-shared-course-initiative/

Ciao Silvia, amazing article! It was really great and inspiring seeing how in the midst of a worldwide crisis that did not allow for travels and more, you and your colleague put all this effort to allow your students to experience language learning in a more immersive and engaging way. Hopefully other instructors can convey the same type of passion for language learning and Italian to their students.

Hi Silvia! Your level of commitment and dedication to your students is truly inspirational. You and your colleague went above and beyond to have these students feel as part of something bigger than just learning a language in a classroom even at a time in which travelling was impossible. I truly enjoyed reading the article! Amazing work

Wonderful article – so much useful information! I love the video exchanges as a way to share culture and community, and the google drive makes sharing user friendly. What a great resource for teachers.

As a student myself it is great to see professors taking initiative and pushing ahead through these challenging times. I wish my professors at my school would start doing this as well, I will be forwarding this article to them right away. Well done!

Fascinating article. What a great experience for the students! Hoping other instructors are able to do the same.