Designing Lesson Plans Around Video-based Annotations

By Amanda Ferris, Coloma Junior High School, and Frederick Poole, Michigan State University

DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.69732/XBWH2759

Introduction

Videos can be used to build students’ background knowledge, provide authentic learning opportunities, and facilitate deeper thinking. It is common to use videos in the language classroom to inspire and motivate students, but whether our students are actively processing and engaging with language in the video is often unclear. This is important in the language classroom because teachers are expecting students to attend to comprehensible input (Krashen, 1985). This input should be rich and meaningful to promote language proficiency. If students are not processing this comprehensible input, then it may not lead to acquisition. This is where digital annotation tools (DATs) can help language teachers monitor student engagement.

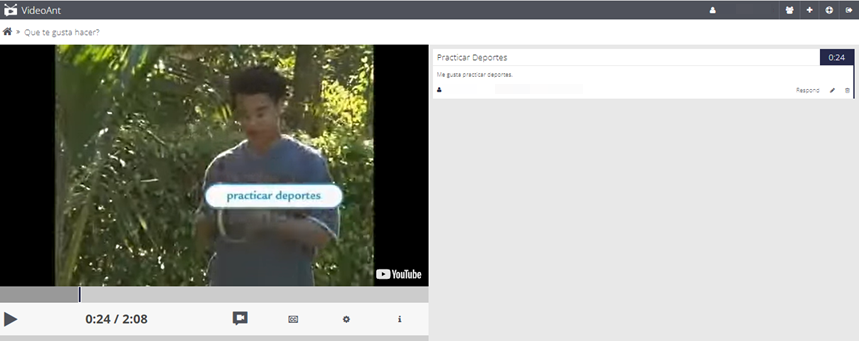

In this article we present a series of ideas and suggestions for incorporating video-based annotations into the foreign language classroom. The primary goal is to provide teachers with a model for different ways to use video-based annotation tools. Throughout the suggested activities, students are asked to annotate different videos using the open source, browser-based annotation tool Video Ant (See Picture 1). Rios (2018) provides an overview of Video Ant for those who are interested in learning more about the tool. In this article, we focus more on what can be done with the tool by creating tasks that ask students to complete a variety of in-class activities that leverage the video-based annotations such as sorting, ranking, and comparing.

Why Use Video-based Annotations?

Schmidt (2010) posits that learners must notice language features and understand them before language is acquired. Similarly, proponents of focus on form argue that learning happens best when students are focused on meaning, but also lend attention to form (Loewen, 2020). In essence, the goal is to draw attention to a target form or structure without disrupting our learners’ attention to meaning. Using annotations to support comprehension in videos may help students notice language features at a higher rate while also requiring them to comprehend the video content. While there is not much research on video-based annotations, research on text-based annotations in digital social reading environments is growing rapidly, and this research can shed light on other types of annotations.

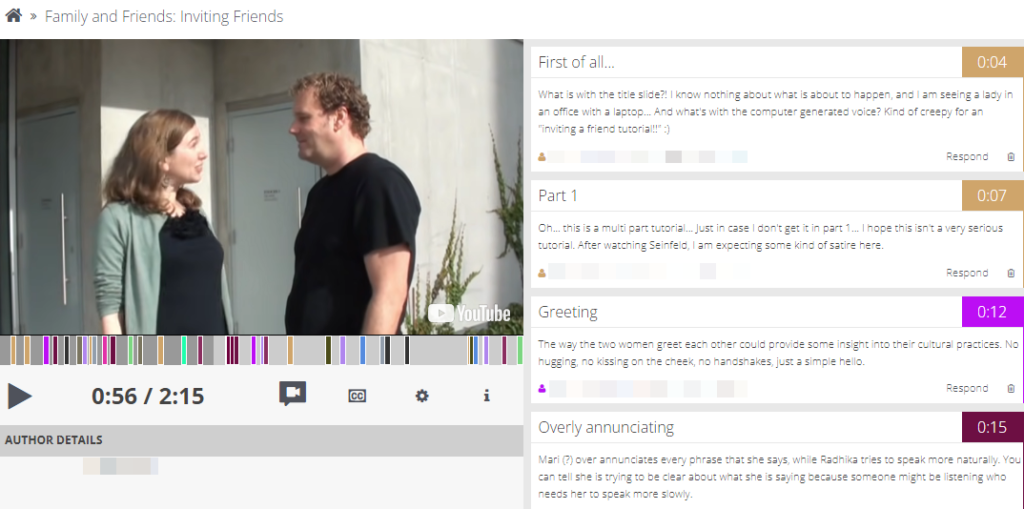

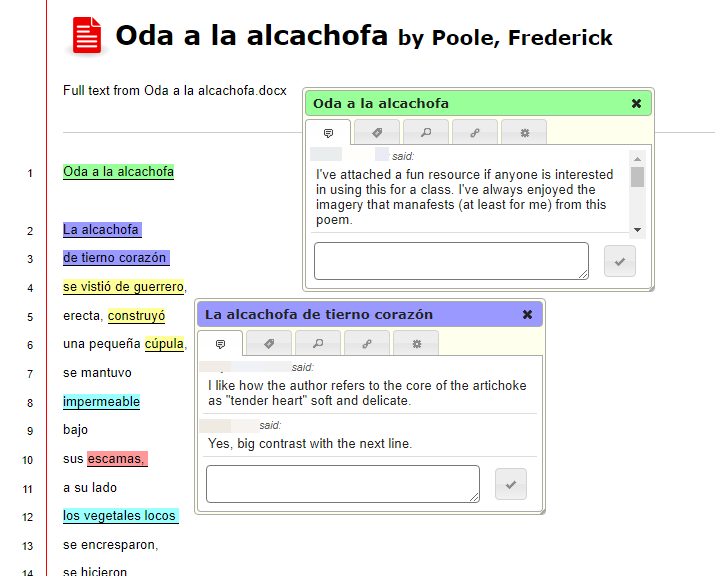

Recently a number of studies have started exploring how digital social reading environments (e.g. eMargin, Perusall) which allow for text-based annotations support second language learning. Text-based annotations in these contexts include both student and teacher generated notes/comments that are embedded into a text (See Picture 2).

Student-generated notes involve selecting a part of the text and then attaching comments, questions, highlights, and/or hyperlinks, among other features. Because these annotations are done in a digital environment, they can be shared with peers, thus creating a more social rather than individualistic experience while reading. This can benefit language learners by not only gaining insight into how their classmates perceived a text, but also by promoting metacognitive awareness. By asking learners to annotate a text in a digital environment, we are pushing them to constantly consider what and how they annotate while reading. Thoms, et al. (2017) investigated the linguistic and pedagogical benefits and challenges using eComma, a digital annotation tool, to promote second language reading in a Chinese language course. The authors noted that “eComma allowed students to co-construct meaning and scaffold their learning while engaged in close readings of the Chinese literary texts outside of the physical classroom” (Thoms, et al. p. 49). In another exploratory study that looked at learner interactions in a virtual space while reading Spanish poetry collaboratively, Thoms and Poole (2017) argue that “it is possible that annotations might help L2 learners not only isolate and remember new vocabulary or better understand specific grammatical structures, but also to monitor their understanding of a text as they decode an L2 reading” (p. 140). Much of this research illustrates how text-based annotations allow for social interactions, unique insights, and an overall improved experience of reading in a foreign language.

In terms of research on video-based annotations, there is currently very little, but it is slowly increasing. Mirriahi, et al., (2018) looked at the effects of instructional conditions and experience on performing arts students’ self-reflections with a video annotation tool on their performances. The authors found that the video annotation tool had a positive impact on the engagement with student reflections. While not used with languages, the use of video-based annotations in this study as a self-reflective tool illustrates how it can be used to draw attention to subtle nuances being analyzed. As suggested above, in this article we illustrate some of the unique ways that video-based annotation tools can be used in the foreign language classroom.

Designing Lessons around Video Annotation Tools

In this article we suggest five ways to use video annotation tools that consider the literature reviewed above. It is important to note that when designing activities for video-based annotation tools, teachers should consider annotation tasks, follow-up tasks, and in-class tasks.

- An annotation task is the initial task that students are asked to do with the annotation tool and usually involves identifying and/or commenting on a language form or phenomenon in the video. These tasks are typically done before students come to class, but if teachers have access to computers, this could also be done in the classroom.

- The follow-up tasks refer to how students will respond to the original annotation task. This might involve asking students to challenge an original post, to offer alternatives to an original post, or simply express an opinion, among other possibilities. While simply drawing learners’ attention to specific parts of a video can be important, designing a follow-up task to complete with the annotations not only provides learners with a second opportunity to return to the video, but it also makes the original task more meaningful as students know that their classmates will be reading their posts. Further, by asking students to return to the comments via follow-up activity, teachers increase the likelihood that students will benefit from their peers’ annotations. Follow-up tasks like annotation tasks likely happen before students come into class, but could also be done within the classroom if needed. However, it is recommended that teachers clearly define a time period for the original annotation task and then for the follow-up task.

- Finally, an in-class task asks students to revisit the video for a third time but now to leverage the information that was collected by their classmates to complete an in-class task. This might involve using suggested changes to a video in the annotations to create a role play, a written assignment that summarizes the annotations, or an oral debate that leverages the arguments made via annotations, among other potential tasks.

Using Annotations to Promote Linguistic Knowledge

For many language teachers, language forms such as vocabulary and grammar may be topics that come to mind first when using video-based annotations to teach languages. A simple linguistic annotation task might ask students to annotate target forms and any associated collocates. For example, if you were to show a video in which some people express their hobbies, you might have students annotate the targeted forms. The title of the annotation could then be used to identify the hobby.

This initial task would help draw learners’ attention to the unique ways that interest is expressed in the target language. As a follow-up activity, students could be asked to respond to the initial annotations with whether they also like the activity mentioned in the video. Finally, as an in-class activity, students could be asked to do a simple count on the likes and/or dislikes expressed by their classmates to determine which activities are preferred by their peers. This could then lead into a discussion about their own likes and dislikes.

In a lesson like this, students are given three meaningful opportunities to engage with the video, but through three different tasks. If students are completing this activity at home before they come to class they have an opportunity to a) receive meaningful input that is scaffolded by their classmates comments and b) engage with the video multiple times as they return to respond to their classmates. This means that there is potentially more time in class to focus on applying language concepts that were targeted in the videos.

Using Annotations to Teach Pragmatics

Video-based annotation tools can also be used to promote students’ knowledge of pragmatics. For instance, you might have a video (or a series of videos) in which a speaker is declining an invitation or engaging in some other pragmatic move. For an annotation task, learners could be asked to highlight the strategies used by the speaker to decline an invitation and then define the strategy in the comment section. As a follow-up activity, learners may be asked to revisit the video and respond to original posts with contextual factors (e.g., power difference, location, intent) that may impact how the pragmatic move was delivered. Finally, in-class activities could be designed to allow students to either act out the scene in a role play or to discuss how they would have declined the invitation if it were them, or in a variety of contexts.

Using Annotations to Teach Cultural Knowledge

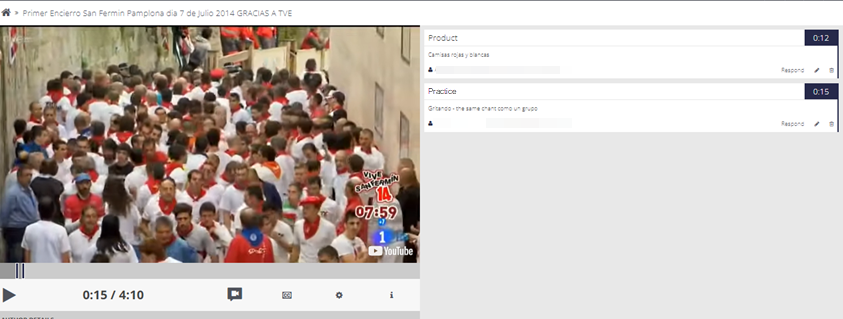

When teaching about culture in the language classroom, we try to help students make connections between products and perspectives or practices and perspectives. Video-based annotations could be used to help students identify products or practices through video annotations. For example, a student below identifies the clothing being worn in the video by saying “camisas rojas y blancas” (red and white shirts), and tags the comment with the ‘product’ label. Another student notes that the people are “Gritando the same chant como un grupo” (yelling the same chant as a group), and uses the ‘practice’ label for the comment.

Then learners could be asked to respond with potential perspectives associated with the products and practices. It is important to note here that while identifying perspectives associated with practices and products can be very challenging (e.g. as noted in Picture 4), the potential perspectives put forth by learners can be used to explore their own assumptions about the world and how they may be similar or different form the target culture. Follow-up activities that involve researching the practices and products could be done to confirm or reject their original hypotheses.

Using Annotations to Promote Creative Storytelling

Since video-based annotations allow for multiple comments and responses, they could also be used to promote creative storytelling by allowing students to reimagine how a narrative might have gone in different circumstances. For instance, learners could be given a short story in video form and then asked to identify key elements in the story via annotations (e.g., main characters, conflict, rising action). A follow-up task could then be designed to ask learners to comment on original posts by reimagining how different characters or a different outcome to a problem may have changed the overall story. A final in-class task might involve students writing a new story using a combination of the proposed changes in the annotations.

Using Annotations to Facilitate a Debate

Finally, annotation tools can be helpful for facilitating a debate in the classroom. The teacher could provide videos that present both sides of the debate. Students could then be asked to highlight arguments made in the debate. A follow-up task could then ask students to write a counter argument for each argument as a reply. Finally, learners could consult the annotations as a preparatory tool before beginning an in-class debate.

Final Considerations and Strategies

1. Adjust Group Sizes and Task Requirements as Needed

There is often a concern that students will have nothing to annotate because their classmates have annotated everything. Video Ant allows you to create groups and multiple videos for those groups quickly and easily. For many of the tasks above you can ensure that everyone has something to annotate by simply making smaller groups (e.g. 2 or 3 people) and then limiting the number of annotations that each person should make in the initial pass (e.g. 2 annotations).

2. Consider Timing Options

If you are doing these as an out of class activity, having students make annotations gradually (an original task on Monday, respond to their classmates on Tuesday, and then complete in-class activities on Wednesday) can be a nice way to ensure that students are engaging with content multiple times with time to reflect.

Conclusion

Video-based annotations can provide a unique way to explore video content in your foreign language classroom. To be clear, we do not recommend that it be used for all of your video-based activities. There are times when using a follow-along guide is more suitable, especially if you are trying to assess individual comprehension. That being said, video-based annotations do provide learners with a scaffolded approach to explore video content outside of the classroom which can then help maximize efficiency of in-class activities. In addition, using video-based annotations allows students to provide insights into video content that their peers may have missed. Finally, by making the video viewing process a social activity, in which students are leaving comments as they watch the video and then responding to their classmates, students may be more motivated to engage in the assigned tasks.

In this article we shared five ways to use video-based annotations in the world language classroom. We reiterate that when designing tasks for video-based annotation tools, it is important to consider follow-up tasks and in-class tasks so that the affordances of such tools are fully leveraged. For additional ideas and pre-made lesson plans you can visit the following website to see some of the materials that were created as part of the first author’s creative thesis project.

Website: https://sites.google.com/msu.edu/ferris-em-project/home

References

Krashen, S. D. (1985). The input hypothesis: issues and implications. London: Longman

Mirriahi, N., Joksimovic, S., Gasevic, D., & Dawson, S. (2018). Effects of instructional conditions and experience on student reflection: a video annotation study. Higher Education Research and Development. 37 (6), 1245-1259. DOI: 10.1080/07294360.2018.1473845

Otto, S.E. (2017). From past to present: A hundred years of technology for L2 learning. In Chapelle, C & Sauro, S., The Handbook of Technology and Second Language Teaching and Learning (pp 10-25). DOI: 10.1002/9781118914069.ch2

Pérez-Torregrosa, A., Diaz-Martin, C., Ibáñez-Cubillas, P. (2016). The use of video annotation tools in teacher training. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences. 237, 458-464.

Rios, M. (2018). VideoAnt: online video annotations. The FLTMAG. February 2018. https://fltmag.com/videoant-online-video-annotations/

Schmidt, R. (2010). Attention, awareness, and individual differences in language learning. In W. M. Chan, S. Chi, K. N. Cin, J. Istanto, M. Nagami, J. W. Sew, T. Suthiwan, & I. Walker, Proceedings of CLaSIC, 2010. Singapore, December 2-4 (pp. 721-737). Singapore: National University of Singapore, Centre for Language Studies.

Thoms, J. & Poole, F. (2017). Investigating linguistic, literary, and social affordances of L2 collaborative reading. Language Learning & Technology, 21 (1), 139-156. Retrieved from http://llt.msu.edu/issues/june2017/thomspoole.pdf

Thoms, J., Sung, K., & Poole, F. (2017). Investigating the linguistic and pedagogical affordances of an L2 open reading environment via eComma: an exploratory study in a Chinese language course. System (69), 38-53. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2017.08.003