Towards Effective, Stress-Free Teacher Training

By Sarab Al Ani, Yale University

DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.69732/CQUT4097

Academic institutions and educators all over the world found themselves faced with the very urgent, very real, and very imminent need to move all education online due to the global spread of COVID-19. They began providing educators with what can be described as crash courses in remote teaching/learning. Everyone started operating in crisis management mode.

These training sessions included managing web conferencing software, designing asynchronous assignments, and envisioning new forms of assessment. Webinars, articles, and other resources started flooding the lives of educators, coming from everywhere and every direction. The luckiest educators had two weeks to prepare, while others had two days. In such circumstances, many educators inevitably felt overwhelmed as they faced a completely new way of operating. Despite the best intentions to provide immediate support to educators, the transition to remote teaching was not stress-free. Educators were unsure whether they would make it out of this semester at all, let alone make it in “one piece,” as the saying goes. Were these preparatory steps helpful? Or did they cause more stress? How can we tell?

Now that the worst part of this phase is behind us, it is worth looking at ways to manage the stress that some language educators may experience when receiving training. By better understanding the reasons behind this stress, by looking at what research recommends in terms of training, we can better assess efforts that aim to provide educators with support. More importantly, it can shed light on the best practices for effective, stress-free training for language educators.

Anticipate Anxiety

Using technology to learn and teach language remotely will inevitably lead to some level of stress and anxiety in both learners and educators who are not very confident in their ability. Perhaps the most important thing training programs can do is anticipate and address this anxiety, rather than hope it will take care of itself. Bitner and Bitner (2002) take it one step further to suggest that anxiety which is associated with teaching language remotely needs to be taken “seriously” in the planning stages. This article proposes several strategies and best practices that may help alleviate this initial stress and anxiety.

Technology Integration Level

When providing language educators with technology training, it is important to look at the skill level these educators already have. Language educators who have basic skills in using technology can easily feel anxious and overwhelmed when being offered training above their level.

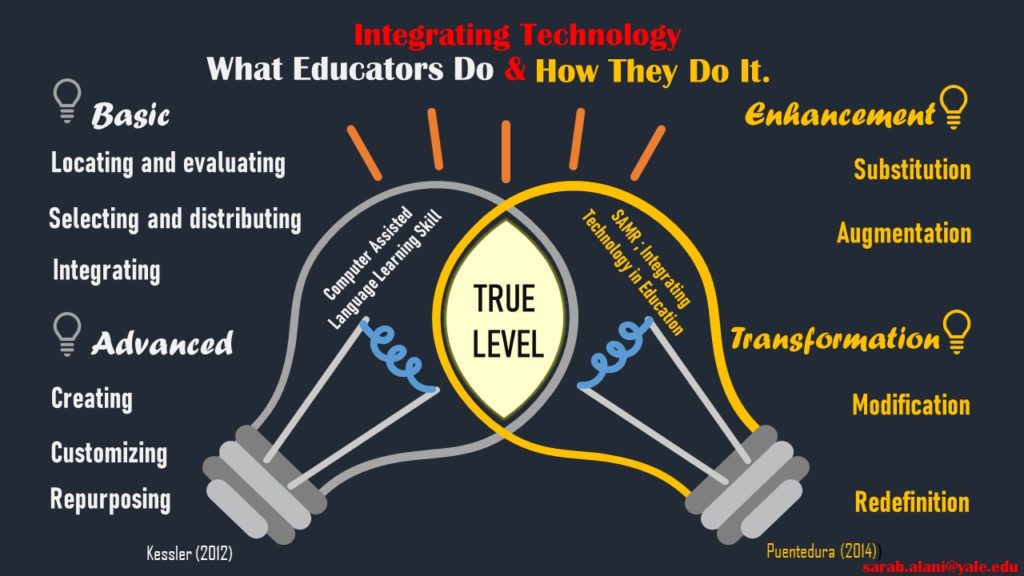

Both Kessler (2012) and Puentedura (2014) have created models that can be very supportive in answering this question, especially when combined.

Kessler (2012) indicates that language educators may show varied skills when it comes to what they do when they incorporate technology in their classes. Basic skill starts with educators using certain technological tools which are at their disposal to locate materials that they might want to use, and to evaluate how suitable they may be for a lesson. After evaluating, they may then select materials that fit best. Finally, they integrate these materials into their lesson. On a more advanced level, Kessler (2012) suggests that language educators might use technology to create their own material. They might also customize, convert, or repurpose other resources that they may have located.

Puentedura (2014) looks at the way technology might be integrated into teaching. This is known as the SAMR Model. Puentedura indicates that at a basic level, technology can enhance teaching by substituting some already existing materials or tools. Sometimes, this substitution introduces a certain educational function that did not exist before. On a more advanced level, technology can transform teaching in two levels. The first is when technology leads to redesigning learning tasks. The second is when technology creates new tasks that were previously inconceivable. Intersecting both Kessler’s (2012) and Puentedura’s (2014) models can be the basis for creating a questionnaire that language educators may be asked to complete prior to training.

Confidence and Degree of Familiarity

Confidence in and degree of familiarity with using technology for teaching can vary from one educator to another. Both elements have a direct effect on the stress that educators may experience when integrating new tech tools in their lessons. Interestingly, these two elements (confidence and degree of familiarity) greatly affect one another. With more familiarity comes higher levels of confidence, which then leads to less stress. Therefore, it is advantageous for training programs to try and identify educators’ level of familiarity with and confidence in using technology for teaching. Specific training sessions can then be dedicated to educators accordingly taking this element into consideration.

Risks vs. Benefits

Among the factors that push language educators towards embracing the use of technology for teaching are the benefits these tools and resources may add to their lessons. Equally, risks or perceived risks that technology may pose on the lessons are among the reasons that lead language educators to avoid the use of technology. The anticipation of significant risks may cast doubt on the effectiveness of a tech tool and thus the need for using it. As a result, if language educators are in a position where they have to use technology, while uncertain about its benefit, then they might experience more stress when using it. Training programs should stress the benefits gained from adding or incorporating technology in teaching language. More importantly, training programs should not ignore the fact that there may be risks involved when using this or that technological tool. Instead, it should be addressed, and language educators should be trained in ways to manage these risks and ways to minimize their effects.

Problem-Solving Strategies

Motivated language educators who wish to incorporate new or more technology in their teaching are not satisfied merely by learning how to work with a specific tech tool, or how to integrate it into their teaching. They are not content even after learning about the risks and benefits of the tool. That’s because they know that technological problems are to be expected.

The anticipation of these problems may lead to stress build-up. The best way to avoid this is to provide educators with problem-solving strategies specific to a particular tool and a particular setting. Acquiring problem-solving strategies enables educators to be in control of solving potential issues, thus reducing stress over that unknown aspect.

Personalized Support

For the training to be complete, language educators need to be provided with support that can address their specific needs. Some educators may think of personalized training as a safety net that grants them a sense of assurance. Personalized training can be more effective than group training. It can take many forms, such as formal training, informal training, peer support, mentoring, coaching, and meetings focusing on adaptation to this new environment.

Topic-Specific Training

Personalized training is effective and can be stress-free as it addresses specific issues. Having adequate resources for this one-on-one kind of training might not always be readily available. In the event of limited training and/or coaching resources, offering training to groups of educators based on the topic they teach might be a second-best option. Chiu (2016) tells us that this type of training correlates with higher levels of self-efficacy. Educators showed improvements in their usage of technology and tech tools when they were given training for tools that were tailored specifically to the topics which they teach, and they scored higher on the self-efficacy and perceived usefulness scale. This may prove beneficial for training programs in two ways. The first is by selecting tools that are specific to language teaching/learning. The second is by offering specific training to language educators as opposed to educators of other topics. It is perhaps worth mentioning here that receiving training on tech tools and programs that are designed for language learning is another way of highlighting benefits and minimizing risk.

Being Selective

Even when selecting tech tools, applications, or programs that are designed specifically for language instruction, Bax (2011) acknowledges that “normalization is more complex and would require a ‘Needs Audit’ to determine the desirability, necessity, and practice related aspects of specific technologies within language teaching and teacher preparation” (p.11). It is important to avoid training language educators to use tech tools merely because it is what everyone is using; rather, be discerning and ensure that educators’ and learners’ needs are met.

Pedagogy Front and Center

According to Liu (2017), negative attitudes, anxiety, and stress towards the use of technology and tech tools in the language classroom may impact educators’ pedagogical beliefs. Therefore, all training and coaching will amount to little value without strong pedagogical foundations. Training programs that are not based on a strong and sound pedagogical foundation can fulfill all eight points mentioned above and still manage to add to teacher stress. Furthermore, pedagogical beliefs are key, as they can even significantly affect educators’ perceptions of how easy technology is to use. For instance, if they believe that integrating technology in teaching leads to better results in learning, then they will be more willing to use technology despite the fact that it may add to the amount of work they have to do. Similarly, teachers’ pedagogical beliefs have also been identified as one of the major barriers to technology integration.

Practical Training

As readers go through this article, they might be pleased to see that their academic institutions do include most of the points mentioned above. It is therefore perhaps disheartening to learn that a number of educators mention a complete or partial lack of training that allows them to experience and experiment with technology and technological tools in a practical manner. Despite the excellent information language educators receive in group training programs, some report having little time to try out these technological tools in actual class settings (Meskill et.al, 2002), as training will have been over by the time they apply these tools in an actual teaching context. Hence some might feel left to manage unknown aspects on their own, which can easily increase anxiety and heighten stress levels. Having practical training that continues after group training sessions are over can help address this issue.

Fried (2011) says; “to be a passionate teacher is to be someone in love with a field of knowledge, deeply stirred by issues and ideas that challenge our world, drawn to the dilemmas and potentials of the young people who come into class each day — or captivated by all of these” (p. 1). This quote indeed describes most language educators. They are keen on enabling their students to learn, see, experience, and live the world in new lights via new language. They also hope to use the best tools available. Designing effective stress-free technology training can have lasting effects for both educators and their learners.

References and Consulted Resources

Bax, S. (2011). Normalisation revisited: The effective use of technology in language education. International Journal of Computer-Assisted Language Learning and Teaching (IJCALLT), 1(2), 1-15.

Bernard, R. (2002). The passionate teacher: A practical guide. Harvard Educational Review, 72(4), 564.

Bitner, N., & Bitner, J. (2002). Integrating technology into the classroom: Eight keys to success. Journal of technology and teacher education, 10(1), 95-100.

Chiu, T. K., & Churchill, D. (2016). Adoption of mobile devices in teaching: changes in teacher beliefs, attitudes and anxiety. Interactive Learning Environments, 24(2), 317-327.

Fried, R. L. (2001). The passionate teacher: A practical guide. Beacon Press.

Hsu, L. (2016). Examining EFL teachers’ technological pedagogical content knowledge and the adoption of mobile-assisted language learning: a partial least square approach. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 29(8), 1287-1297.

Kessler, G. (2012). Language teacher training in technology. The encyclopedia of applied linguistics.

Kessler, G., & Hubbard, P. (2017). Language teacher education and technology. The handbook of technology and second language teaching and learning, 278-292.

Liu, H., Lin, C. H., Zhang, D., & Zheng, B. (2017). Language teachers’ perceptions of external and internal factors in their instructional (non-) use of technology. In Preparing foreign language teachers for next-generation education (pp. 56-73). IGI Global.

Meskill, C., Mossop, J., DiAngelo, S., & Pasquale, R. K. (2002). Expert and novice teachers talking technology: Precepts, concepts, and misconcepts. Language Learning & Technology, 6(3), 46-57.

Puentedura, R. (2014). SAMR model. Technology is Learning.