Teaching Materials in the Digital Age: Using and Sharing Images and Video Responsibly

|

|

|

INTRODUCTION

As educators, we are often hyperaware of the issue of intellectual property: we actively maintain folders (or bookmarks) of articles so we can cite sources for conference presentations; we nod approvingly when we see that attribution was provided where due; and we admonish our students for their lackadaisical attitudes towards copyright and copying. But how many of us regularly search Google Images and right-click to “Save Image to Desktop”?

When the photocopier was our only means to reproduce materials, things were harder, sure. To add one image to a handout, we shrunk the original image using the photocopy machine, cut it out, taped it to the handout and then hit “Copy.” Yes, it was a challenge, a waste of time, a waste of paper, and the end result was often flawed, but at least, in those days, the likelihood was nil that anyone who cared would discover our use (and illegal reproduction) of their photograph. Oh, how the world has changed!

You are now likely saying to yourself, “but my cultural activities need images and video to illustrate phenomena to my students. As long as I’m using my Google Images for educational purposes, I’m safe under the TEACH Act or Fair Use, right?” Unfortunately, the digitization of teaching materials increases personal risk when it comes to using copyrighted materials.

In this article, we will review the basics of Fair Use and the TEACH Act and then will go over several scenarios to help you make responsible choices when sharing materials online. Please note: we are not lawyers! See this article as a starting point. If you have further questions, we encourage you to contact your institution’s legal department or library. We will now dangle a carrot as enticement to keep you reading… you can still use Google Images to add zest to your teaching activities, read on to learn how to do so responsibly!

COPYRIGHT, FAIR USE, TEACH ACT, OH MY!

Ah, copyright. You know it’s important, but it’s so complicated…. You know you really should have looked at it last summer when you had all that time, but it’s so dull….

Yes, copyright may bore most people, but it is an important part of being an educator in the 21st century. This section will give you a brief definition of what copyright actually means before we move on to examine how we can act ethically within these laws.

So what is copyright? Simply put, it’s “a form of protection grounded in the U.S. Constitution and granted by law for original works of authorship fixed in a tangible medium of expression.” In short, copyright is a legal right for authors (as well as artists, coders, movie and theater directors) to publication or sale of their work. Naturally, there are a few more criteria—the work must be creative, as opposed to fact-based, and it must be tangible, for example, recorded or written down. There is a limit for copyright too—it gets complicated, but as a rule of thumb, copyright has expired on material published in the US before 1923.

The other important fact is that copyright was originally established in the belief that compensation encourages creative work for the good of society—rather than to lock down resources, as many people believe its purpose is today. Despite this cheery original meaning though, these rules have a huge influence on what we can use in the classroom, so read on to find out what your options are.

USING SPECIFIC OBJECTS (e.g. a specific image of an apple or a portion of a film)

Have you ever decided not to use your favorite movie in class because you think that copyright laws make it more trouble than it is worth? While using specific materials can be problematic, it is possible to use most media materials in your face-to-face classes. This section will outline some of the options available to you if you want to use a specific copyrighted object in your class, such as getting permission, linking, assessing Fair Use and relying on the TEACH Act.

Scenario:You’re a Spanish teacher trying to teach your students about ‘curanto’, a famous meal from the island of Chiloé. You’ve found an amazing picture on Flickr, but when you had a look at it, it said “All Rights Reserved.” You decide to look for another option, but can’t find anything else. It has to be this picture!

|

The second option available to you is to provide a link out to the photo or video rather than reproducing the image in your own material. You will not incur any liability if you are not actually hosting the material on your site or course page. Obviously such a hyperlink will work only with born-digital materials or works that have been digitized. You must also ensure that you are linking to the original work, rather than to an unauthorized copy. If you choose this option you may also run into long-term preservation issues if the original material is moved or deleted.

The third option available to you is to assess whether your use of the image or video would be covered under Fair Use. Many educators have heard the phrase “Fair Use” before, but may have a hazy idea of what it actually means in practice. If you need to use a specific work in your class though, Fair Use will likely be your most realistic option. So what does Fair Use actually mean? In effect, Fair Use is “any copying of copyrighted material done for a limited and “transformative” purpose, such as to comment upon, criticize, or parody a copyrighted work.” In other words, Fair Use allows you to use copyrighted material in specific ways, for specific purposes, without having to ask permission from the author. So far, so good.

However, note that this definition doesn’t give you blanket permission to use the work, nor does it explicitly exempt educators from copyright rules! Instead, it very cautiously states that you may be able to use a specific work if you fulfill certain conditions. And while these conditions generally include educational use, they sometimes do not. In effect, Fair Use protects educators only to a certain extent—and as this is copyright law, there are no hard-and-fast rules about what this actually means. So how can you determine whether your borrowing is permissible under Fair Use? You will want to consult the four factors that a court would consider in determining whether or not a particular use is fair:

-

The purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes

-

The nature of the copyrighted work

-

The amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole

-

The effect of the use upon the potential market for, or value of, the copyrighted work

As clear as mud, right?! While these factors seem logical, they are likely too abstract to help the majority of us. Further complicating matters is the lack of a definitive list of acceptable uses. Instead, librarians and lawyers have come up with the following list of scenarios, which tend to favor or oppose Fair Use:

|

Favoring Fair Use |

Opposing Fair Use |

|

Teaching |

Commercial Activity |

|

Research |

Profiting from Use |

|

Scholarship |

Entertainment |

|

Non-Profit Educational Institution |

Bad Faith Behavior |

|

Criticism, Comment, Parody |

Denying Credit to Original Author |

|

News Reporting |

|

|

Transformative or Productive Use |

|

|

Restricted Access |

So in the case of the photo, if you plan to use an image in a class PowerPoint to illustrate your lecture on Chilean food, it would probably classify as Fair Use as you are using the photo for teaching, for a non-profit educational institution, for commentary and it has restricted access (your classroom). Another very important aspect is that my use is transformative, which means that “the original material becomes a part of something new, new meaning is created, or it does not compete with the original material on the market.” In other words, the photo wasn’t created as a teaching aid. Therefore, by using it in this way in my classroom, I can claim that I have irrevocably transformed its purpose—another good indication that my use would fall under Fair Use rulings. However, if you then used the same photo on a flyer that you created to advertise copies of the anthology that your class wrote about Chile, then that would likely not fall under Fair Use as you are profiting from the photo. Another aspect to consider is what you do with your teaching materials afterwards. If you want to make them available to your students later, then it will be easier to claim that you are taking steps to protect these images if you upload them to the school’s learning management system, where your PowerPoint will be padlocked behind a password. If, however, you prefer to use an open system for your class or course, protecting materials will be more problematic. One workaround that we have seen used is to upload a PowerPoint into VoiceThread, and be sure to disable the option to download. where the default option does not permit downloading. You can verify your “Playback Options” in the “Edit” page of your VoiceThread.

What’s important to remember here is that this list is provided only as guidance—and that you, as an educator, are not automatically exempt from the rules. Instead, it is the broader context of the material that is important in ascertaining Fair Use. In other words, you cannot apply preemptively to get your materials “passed” for Fair Use. Instead, Fair Use and the four factors would be used to judge your case only if you were sued. For this reason, if you are at all worried, and think that you may want or have to claim Fair Use as a reason for using a specific material, it is important that you cover your back by documenting your rationale and reasoning for doing so. You will then be one step closer to proving that you were trying to act in an ethical manner if your usage was ever questioned. The Fair Use Evaluator from the American Library Association is an example of a simple program that can help you document this process. This straightforward tool presents a series of questions that allows you to describe and assess how your proposed usage meets principles of Fair Use. At the end, it will compile all your responses into a PDF that can be printed or saved with your other course materials, ready to be produced in the unlikely event that you receive a copyright infringement notice. This extra precautionary step serves a useful precautionary purpose that may seem excessive but should help even the most cautious feel confident about meeting all copyright eventualities.

In sum, Fair Use is likely to be the most practical way to protect yourself from copyright infringement. While the four factors used to ascertain coverage may seem vague or subjective, the use of tools such as the Fair Use Evaluator provide an easy way to protect yourself against nasty surprises.

The final option available to you as an educator is to rely on the TEACH Act, whose very name implies its appropriateness to educational usage! However, while the TEACH Act was passed in order to offer specific protection to educators, and especially online educators, its reach is actually fairly limited, and many experts believe that you may be better off relying on claiming Fair Use. However, if you want to use specific materials in an online course, it could be a relevant option. In a nutshell, copyright law provides educators with the right to perform and to display others’ work. However, until 2002, this was limited to classes that took place in person, in a physical classroom. The TEACH Act, which stands for the Technology, Education, and Copyright Harmonization Act was an attempt to extend the same rights to the online classroom. In other words, online or distance educators have been allowed to make movies or audiovisual materials available to their students since 2002. However, unlike in the physical classroom, this act does not give you permission to upload an entire movie online. Instead it allows you to display only “reasonable and limited portions” of works, otherwise known as clips. In this case, if you are an online educator, and you need to show a particular movie in its entirety to your class, the TEACH Act doesn’t really help you. Instead, you would be better off using Fair Use principles to document and justify your actions.

In sum, if you need to use a specific material in your class, you have three or up to four options that can help you do so legally and ethically: asking permission, linking, claiming Fair Use, or—if you are an online educator—relying on the TEACH Act. While all of these options involve a few extra steps, it is possible for the most part, to use specific copyrighted work for educational purposes. If, however, these steps seem excessive or you are not limited to using a specific item, the next section will highlight alternative and much easier ways to use media ethically in your class.

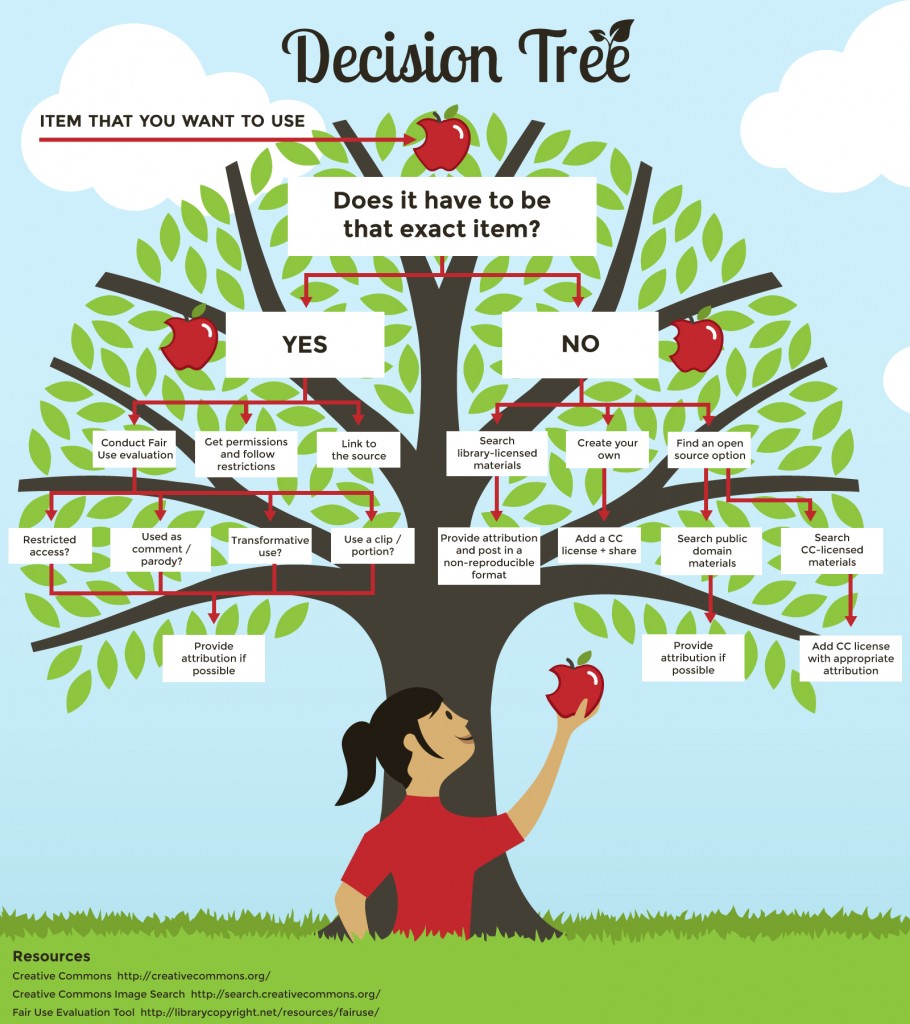

Fair Use Decision Tree by FLTmag is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution

Fair Use Decision Tree by FLTmag is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

USING NON-SPECIFIC OBJECTS IN YOUR CLASS (e.g. any image of an apple)

In cases where you need a general image or video clip, as opposed to a specific one, and are open to different possibilities regarding what it might look like, you have many more options. A sensible way to begin is by making a quick visit to your institution’s library. It is likely they have already licensed access to the resources of one of the larger media outlets, like AP Images, so be sure to ask! Your next choice for open license media is just a few clicks away thanks to the trend of openness and non-profit organizations such as Creative Commons.

|

Scenario: You’re a French teacher and you want to show your students a short video clip that illustrates the 14th of July. You don’t care about the exact content of the video, but for the purpose of the activity, you need to embed the video directly into your open (non-password protected) blog. |

Creative Commons’ primary mission is to open up the world of copyrighted material, while still allowing authors to set the parameters for others who wish to use their original works. They took the © of copyright and morphed it into a “CC,” thus creating an alternative license to the padlock of copyright. By visiting http://creativecommons.org/choose/, photographers, authors, and teachers alike can customize their own CC license for their own original works.

There are several licenses available on this site. The default Creative Commons license simply requires that anyone wishing to use the work provides an attribution to the original creator of the work. Other licensing options restrict adaptations, restrict commercial use, and require Share-Alike (the next person who uses your work must share their work with the same license).

In addition to providing licensing, the Creative Commons website also allows you to conduct targeted searches for Creative Commons licensed materials via Google Images, Flickr, YouTube, Open Clip Art Library, and Fotopedia. Visit http://search.creativecommons.org, enter your search criteria, and then select the media source(s) you would like to search. Alternate resources for open-licensed materials are popping up everyday as the trend of openness catches on. Wikimedia commons, for example, publishes only images and media that are freely licensed or in public domain. Within this set of resources are the series of Nuvola Icons, icon-like images that you can use freely, although some may require attribution. Another resource for open images is Iconspedia, where you can select your licensing preference (CC or free) before conducting each search. In all cases, remember to follow through and verify that any resource you intend to use does indeed include a CC open license. If you wish to reproduce the original work in your own materials, remember to provide attribution back to the original creator.

The way you provide attribution will depend on your unique circumstances and the information available about the original work. In most circumstances, a caption below the image or the video will suffice. If you have access to the creator’s name, the title of the work, the Creative Commons license and can hyperlink text, you should include all of that information and link back to the creator’s website or profile (for Flickr or YouTube) and also hyperlink the license as well. See these attribution examples provided by Creative Commons. If the original resource is from Flickr, YouTube or another source where full names are not the convention, add a caption with the username of the account owner, for instance “Flickr maestracourtney.” If the image is part of a presentation, a more practical and less obtrusive attribution could be incorporated into the last slide in a “resources” page.

LICENSING YOUR OWN MATERIALS

As you create your own teaching materials, consider taking the next step and contributing back to the world of open resources. Grammar activities, cultural simulations, and even vocabulary review are in high demand by other teachers, especially those of less-commonly taught languages. There are a few steps you should follow to ensure that you are responsibly contributing to web-based repositories.

First, review the activity to be sure that you either authored all of the content yourself or provided the appropriate attribution when needed. The next step is to select a Creative Commons license and add the license to your work. When selecting a license, you should check to ensure there are no conflicts between your overall license for your activity and any other licensed work you have used.

There are numerous web-based repositories for sharing teaching materials, but it’s increasingly likely that your school or language department already has a collection of such materials. MERLOT.org is one of the most well-established repositories for all teachers and MERLOT is always welcoming new submissions; once you create a free account, you can upload or link to your teaching resource from their web portal. The website TeachersPayTeachers is an open marketplace where teachers pay for permission to use your original materials, and thus it offers you an opportunity to turn your dedication to high-quality teaching materials into some pocket change. By licensing your own original work and contributing back to the world of open resources, you can feel warm and fuzzy that you have now closed the loop in the cycle of responsible sharing.

WHY IS THIS IMPORTANT?

As you can see, copyright issues can be a bit of a minefield. Is it really worth it? Does anyone ever get caught? Don’t we always get a free pass as educators anyway? Well, yes, in most cases, educators can demonstrate and claim Fair Use of materials. However, don’t forget that media companies are getting stricter about usage of their materials. While we marvel at the abundance of online and seemingly free images and videos, companies can use the same digital tools to find infringement of their copyright far more easily than before. In addition, infringement does not come cheaply. Damages can start at an eye-watering $2,500 per image, although they could stretch into a five figure sum! The explosion of digital content and online activity means that there are many borderline use cases too. Take a magazine like the FLTmag—while it is based at the University of Colorado and is designed for educators, it does show advertisements. So, is it for- or not-for-profit? Either way, the risk doesn’t seem worth it, especially as there are a number of simple solutions to these educational copyright conundrums.

In addition to lowering your own personal or professional liability, there are other incentives for adopting responsible sharing practices. One of the major reasons is to engage students in habits of digitally literate learners. Though the power to share and create knowledge and information both legally and ethically has always been important, it has new resonance in the age of social and intellectual online networks, or what Henry Jenkins refers to as participatory cultures. For instance, learners must be able to engage with responsible sharing habits in order to curate or create digital artifacts as well as to contribute to and collaborate in online dialogues. These competencies are essential to foreign language national standards, but require a grounding in responsible online participation. Furthermore, many teachers and librarians recognize that students, in spite of having grown up with online technologies, still have much to learn about social awareness and skills for digital environments. Educators can help develop these digital literacies and capacities through classroom activities. However, more importantly, we can also model these habits by complying with copyright and sharing guidelines and rules in our own teaching materials and presentations. After all, if students see that their teacher or professor pays scant regard to ethical attribution of authorship or provenance, what motivation will they have for doing otherwise?

Lastly, copyright laws do not benefit Disney or predatory media conglomerates alone! Responsible sharing can also give more credit to you as the author or creator of innovative teaching materials. A Creative Commons license on your work could provide you with monetary benefits as sites such as Teachers Pay Teachers enable educators to “buy, sell, and share their original resources.” Getting attribution for your work could help you establish or develop your online presence too, perhaps launching your career as a successful educational blogger. Attribution could also help you professionally. In institutions of higher learning at least in the United States, excellence is generally recognized through research activity, such as the publication of a peer-reviewed article. Teaching achievements may not be considered as important, even though teaching materials, are often seen and used by a far greater number of people. Licensing your work will help you to track and measure its usage and impact, and can more generally help educators to advocate and gain recognition for teaching activities too.

By Alison Hicks, Romance Language Librarian, Norlin Library, the University of Colorado Boulder.

By Alison Hicks, Romance Language Librarian, Norlin Library, the University of Colorado Boulder. By Courtney Fell, Foreign Language Technology Specialist at the Anderson Language & Technology Center, the University of Colorado Boulder.

By Courtney Fell, Foreign Language Technology Specialist at the Anderson Language & Technology Center, the University of Colorado Boulder.