Teaching Languages to Students with Learning Challenges: The Role of Technology

By Eve Leons, Associate Professor, Landmark College.

By Eve Leons, Associate Professor, Landmark College.

“Just be patient with me don’t give up on me…. I also want to do really well in this class not just pass it but do really well.” – Landmark College Student.

Imagine being told by your Italian teacher, “If you sit in the back of the class, keep quiet, and do other work, I’ll pass you.” Imagine being this student: “I took Hebrew, but I couldn’t keep up, so I just stopped going to class.” Or these students: “I took three years of Spanish in high school. Most of it went out the other ear.” “Some words I have trouble enunciating. For example, ‘enunciate.’” “I have dyslexia. As a child people couldn’t understand me. I did speech therapy for many years.” “I become overwhelmed if I am falling behind and I sort of give up like I always did.” “I don’t find it easy to talk to others the same age.”

For the past 20 years, I have taught Spanish at Landmark College, which specializes in providing high-quality education to students with learning differences. Stories and sentiments like these are not uncommon; I work with my students in small classes, so I get to know them well. In reviewing their psychoeducational testing over the years, I often see terms such as dyslexia, language-based learning disability, phonological processing disorder, auditory processing disorder, attention deficit (with or without hyperactivity) disorder (ADHD), autism spectrum disorder, nonverbal learning disability, and executive functioning disorder. In many ways, however, these labels provide very limited information; they do not reflect my students’ extraordinary diversity, creativity, and abilities.

I could say that my students do have one thing in common: A wish that closed captions would magically appear when I speak, and that I came with stop, pause, and replay buttons. This realization led me to seek ways to underpin their learning through technology. Since each student is unique, needing different supports at different times, the tools I use most are fairly simple authoring tools. These allow me to create material that reinforces my curriculum and to easily modify what I have created, based on student feedback. Of course, I also offer my students opportunities to practice with all kinds of web-based educational products. I have found that the most useful of these share specific characteristics and avoid certain pitfalls. In this article, I will describe the features I look for in practice materials and also discuss tools widely used in the field of learning disabilities to address specific skills or needs. First, it will be useful to review common areas of challenge for students with learning differences in the language classroom, strategies that tend to be successful, and a bit about my context.

WHY STUDENTS STRUGGLE

Over the past few decades, much has been written about why certain students tend to struggle in their world language classes despite their solid efforts, as well as how to best serve this population in their language learning. Most challenging are students with language-based learning disabilities. This term refers to a range of difficulties manifesting with different levels of severity that affect the ability to understand and use spoken and written language. One student might have difficulty at the level of phonemic awareness, struggling to process the sounds of the language and retrieve them with adequate pronunciation. Another, with a poor appreciation for the rule systems of language, may not readily see patterns. A student with an auditory processing disorder may find it harder to parse the speech stream and therefore harder to understand oral language. At times, students with learning differences struggle in world language classes because what a teacher regards as “comprehensible input” may not in fact be comprehensible to a student with weak language processing skills. Often, basic factors such as small font size and busy layout on a textbook page interfere with learning.

Perhaps more at risk of academic failure are my students with ADHD and executive functioning issues. They tend to miss classes, fail to complete homework, and neglect to make up tests and quizzes. My students on the autism spectrum may have difficulty negotiating the social elements of the classroom, be overwhelmed by sensory input, or get stuck on certain assignments. In my experience, however, they tend to excel at memorization, homework completion, class attendance, and test taking.

STRATEGIES FOR SUCCESS

In the late 1990s, Landmark College and the School for International Training embarked on a three-year study to identify best practices to support students with a wide variety of cognitive profiles in their language learning. The study was underwritten by the U.S. Department of Education Fund for the Improvement of Postsecondary Education (FIPSE). The research identified the following strategies:

-

- Make careful curricular choices

- Be conscious of pace

- Provide one-on-one instruction and give students access to tutors

- Structure activities for success

- Create a supportive in-class environment, encourage student-faculty contact, monitor affective issues, and make language learning fun

- Actively employ learning strategies in the classroom, help students become more strategic, and foster metacognition

- Build in support for students with weak language processing

- Use multimodal (multisensory) teaching methods

- Structure activities for success

- Use instructional and assistive technology whenever appropriate.2

While all of these strategies are valuable, I put special emphasis on supporting all of my students, including those with weak language processing, by using instructional and assistive technology to create a multimodal learning environment, structured for success. Indeed, teaching with technology is a natural fit for this population, and I have become a connoisseur of free and low-cost materials available on the web that I can use to create practice materials relatively quickly to enrich my curriculum.

MY TEACHING CONTEXT

Although it is not uncommon for me to teach high-level students or heritage speakers who have had significant language exposure outside of the classroom or in the home, I primarily teach beginner and intermediate level classes. On the surface, my classes probably look typical. I gravitate toward a practical task-based curriculum that integrates many of the NCSSFL-ACTFL Can-Do Statements. Students talk their way through scenarios they would likely encounter in their daily lives or when traveling. They demonstrate their command of the language using a process that moves from writing to speaking. We integrate mnemonics and memory aids whenever possible to facilitate language retrieval. We use video, songs, and web-based practice materials both in and out of the classroom as a primary means of instruction. I avoid workbook-type activities (sentences with missing words, crossword puzzles, matching), since my students tend to find them overly confusing and I can offer them more effective means of practice. Currently, my students have only limited classroom access to Mac products, but I seek out programs that work across devices and operating systems. My end goal is to create opportunities for students to gain confidence in their ability to communicate in a culturally and linguistically diverse world.

MATERIALS DESIGN

The study of how to improve instruction and accessibility to best serve the needs of all learners, including those with disabilities, has been a mainstay in the fields of Universal Design for Learning (UDL) and disability for some time. Small differences in design can have a tremendous impact. It is worth noting that while all students “benefit” from these features, students with learning differences may in fact need them to succeed. Tremendous strides are being made in the field. Mac OS X comes standard with an array of accessibility features. Designing learning materials is a complex process, since each learner is unique. What is “sufficient support” can vary from learner to learner and according to the task at hand. Within all the complexity, however, I have come to understand which materials tend to address certain challenges my students face, and learned to recognize the attributes that make them effective – or not.

As a language teacher, when I look at web-based practice materials, I ask the following questions:

- Can the learner control the amount of material being practiced? Can the learner control the pace of instruction, or is there a built-in speed component that can interfere with learning?

- Does the program give rapid, effective learner feedback?

- Is language presented in a way that is sufficiently multimodal? Are there visual (written word/picture), auditory, and tactile ways for students to interact with the material?

- Is practice available in multiple, interactive formats?

- Is the learning activity structured for success?

I’ll go into more detail about these key questions below:

- Can students control the amount of material being practiced? Can the learner control the pace of instruction, or is there a built-in speed component that can interfere with learning?

Students with learning differences typically benefit from being able to break down complex content into smaller chunks or “micro-units.” Often, I find that students are overwhelmed by the information presented on a typical textbook page; they don’t know where to begin. Materials that present information in learnable chunks, and those that allow students a means to control the amount of content they are practicing, tend to be the most effective. For my students who might have slow processing speed, the ability to control the pace of the activity is critical.

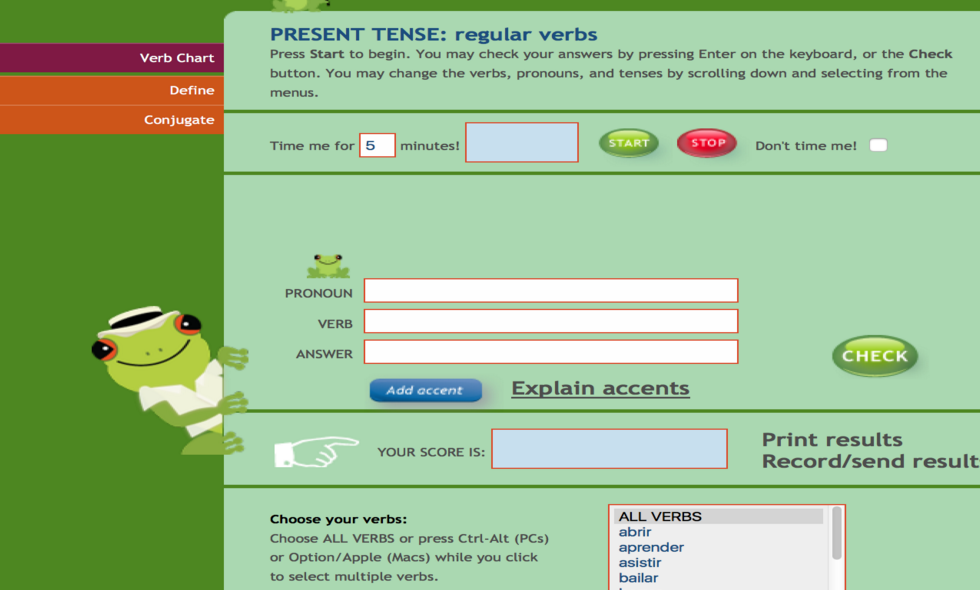

STUDENT CONTROL OF AMOUNT OF CONTENT: CONJUGUEMOS

On Conjuguemos, a site designed for practice of verb conjugation in six different languages, the learner can choose to practice using all the personal pronouns or just one. For some of my students, this feature makes the difference between success and failure. Being able to micro-unit the task gives them a doable starting point. I would like students to be able to choose two personal pronouns to work with at a time, but that feature does not currently exist. Note that students also have easy access to references and can choose which verbs to practice.

- Does the program give rapid, effective learner feedback?

Rapid feedback keeps the learner from inadvertently practicing or reinforcing incorrect language. Computer feedback has the added benefit of being private and objective.

RAPID FEEDBACK: QUIA

In this Quia activity, green trophy images appear when a correct match is made.

- Is language presented in a way that is sufficiently multimodal? Are there visual (written word/picture), auditory, and tactile ways for students to interact with the material?

What is “sufficiently” multimodal varies from person to person. In a practice activity, I hope to give students the sounds of the language, access to the written word, and a physical way to interact with the content.

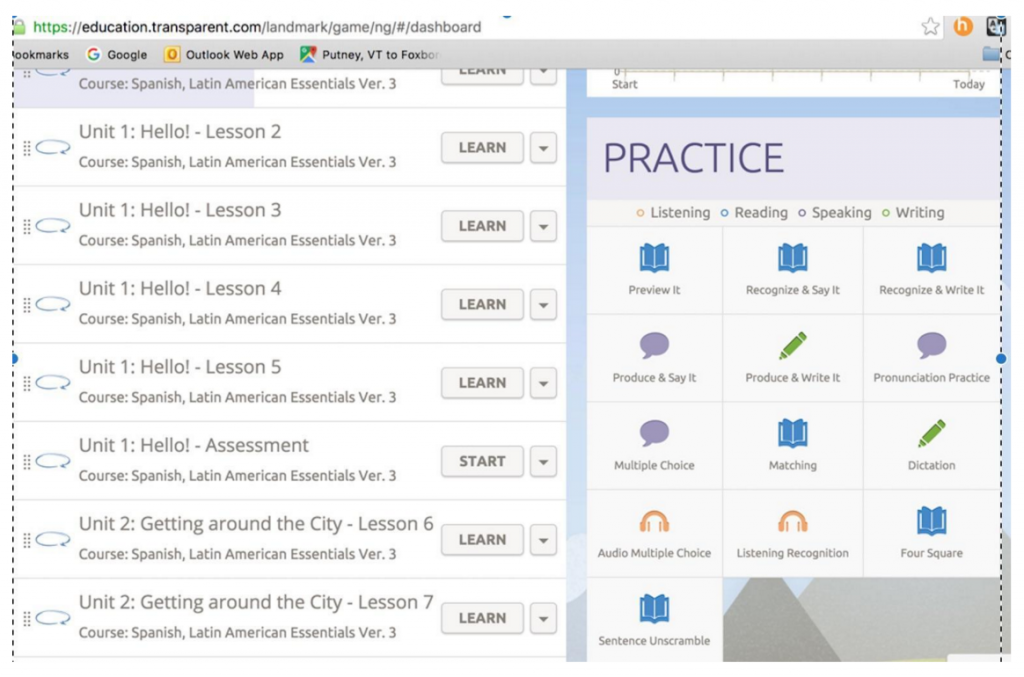

ILLUSTRATION OF MULTIMODAL PRACTICE: TRANSPARENT LANGUAGE ONLINE

In Transparent Language Online the learner goes through a cycle of multimodal practice: Preview It, Recognize and Say It, Recognize and Write It, Produce and Say It, Produce and Write It, and several supplementary activities. Students appreciate being active in the learning in this program.

- Is practice available in multiple, interactive formats?

As a busy teacher, I love programs that let me input content just once and then let students access it in multiple formats without any additional work on my part. Students most appreciate fun, painless practice. A current favorite is the Scatter game in Quizlet. While students are “timed” in this practice game, there is no time limit. The task completion time is recorded, and the learner is encouraged to try again for a better score or faster time. This approach serves all of my students – those who process information more slowly, and the competitive ones who are motivated to bring down their times. While the Scatter game itself does not have sound, sound is automatically available in other practice sets that students can easily access. As Scatter tests recognition of material, I encourage students to move from that game to others that allow them to practice retrieval.

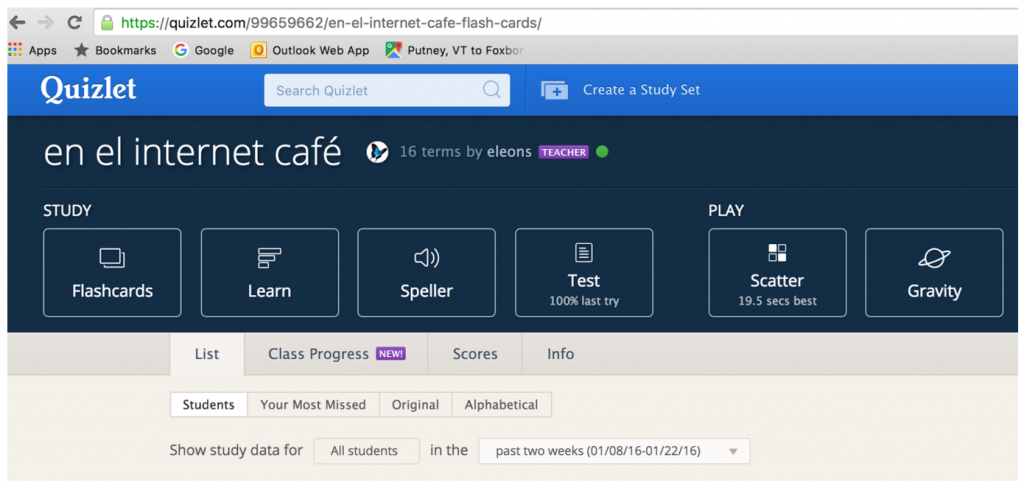

ILLUSTRATION OF MULTIPLE INTERACTIVE FORMATS: QUIZLET

Quizlet offers the learner six different ways to interact with the material. Sound is available in some but not all practice materials.

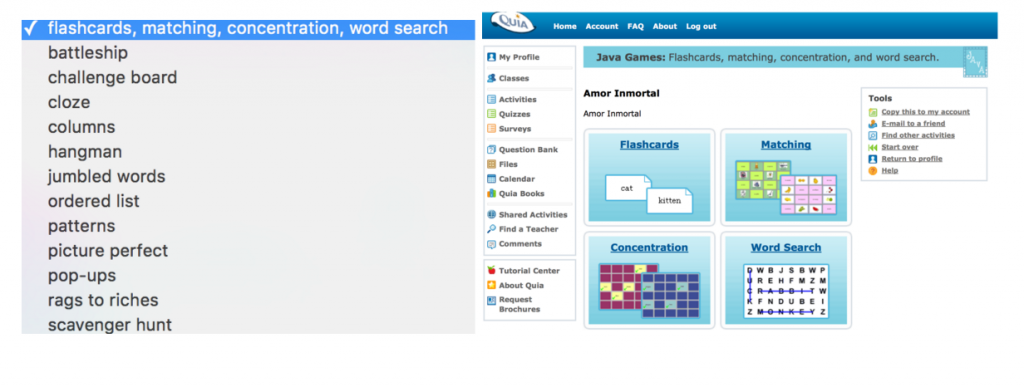

ILLUSTRATION OF MULTIPLE INTERACTIVE FORMATS: QUIA

Quia likewise offers an impressive number of fun interactive practice materials (though sound, a critical feature, is not automatically generated). When the teacher creates one list, students are automatically offered flashcards, matching, concentration, and word search.

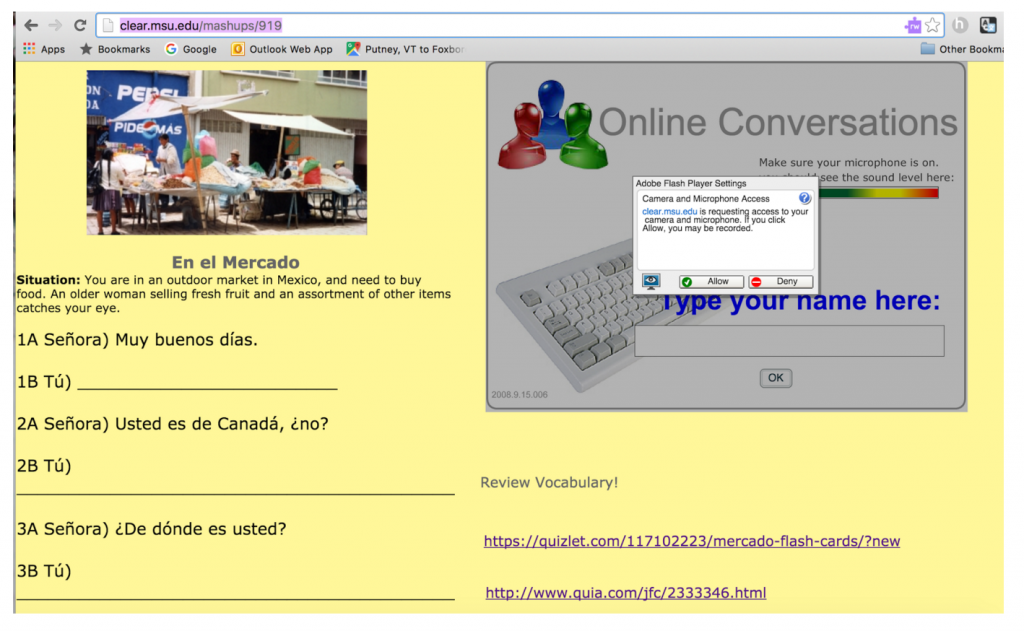

ILLUSTRATION OF MULTIPLE INTERACTIVE FORMATS: CENTER FOR LANGUAGE EDUCATION AND RESEARCH (CLEAR) RICH INTERNET APPLICATIONS (RIA’S)

Impressive (and free of charge) are the CLEAR Rich Internet Applications (RIAs).

Mashups give teachers the ability to easily integrate audio, video, text, and practice materials in a variety of formats. Mashups can house a learning sequence. For example, a Mashup might include written text from a scene we are working on in class, authentic material such as a song, menu, or map, practice links for vocabulary, conversation practice or a dropbox. I most often use the CLEAR Mashups, Dropboxes, and Conversations. Viewpoint can be used to add closed captioning to video as needed to make oral language visible.

- Is the learning activity structured for success?

Is the learner working with a manageable chunk of language? Are resources clear and easy to access if a learner needs support? Is the learning task doable? Is it fun? Is sound available and of high quality? Can the size/color of text be altered?

Since my students tend to have experienced academic failure, I try to give them practice opportunities that set them up for success. Features such as built-in reference tools and support for spelling and weak auditory processing are essential. Programs that rely on perfect spelling are likely to be problematic. Students with slow processing or auditory processing difficulties may flounder in activities such as “listen for the missing word” without aid. Students with pronunciation issues may find it impossible to navigate programs that rely on speech recognition. Most troublesome are programs that block a student from continuing if they get an answer “wrong”. Also a source of stress are practice materials that do not automatically record a student’s progress. Students appreciate being able to do part of a practice unit and then return to it later without losing their work.

The power of engaging, well-designed learning practice should not be underestimated. All of my students, and especially those with attention issues, are motivated by materials they find enjoyable. People with ADHD can find it nearly impossible to maintain focus in situations they experience as boring, and activities without a strong interactive component will not hold their attention for long.

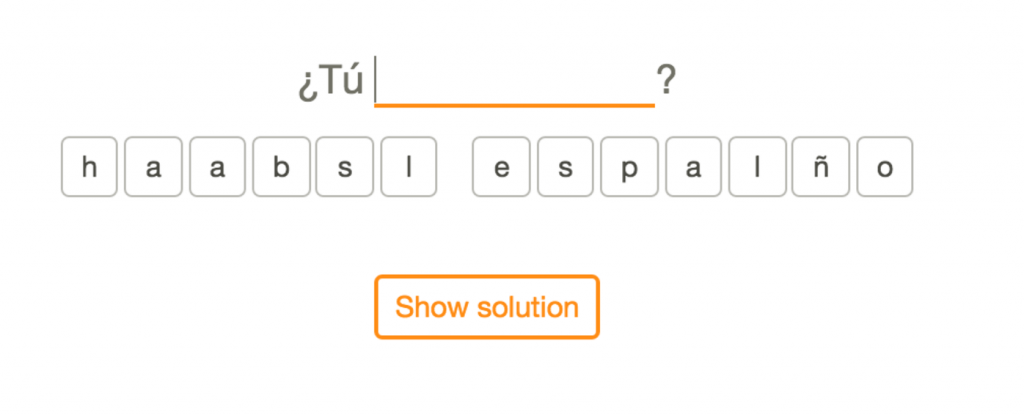

ACTIVITY STRUCTURE FOR SUCCESS: BABBEL

Here is an example of how Babbel supports practice at a beginner stage of new content retrieval. The letters are provided and the learner is asked to type the answer (or click on the letters), using the letters provided below for a memory and spelling boost. A student who needs more support can click on “Show solution.” (Note: a reduced amount of typing may also help learners with physical disabilities.) This works well for my students with poor spelling skills.

A learner who selects “Show solution” can see the word but still have the benefit of typing the answer. A learner who prefers not to type the answer can click on “Solve,” which completes the sentence, and then move on. This ability to choose a level of interaction keeps students invested. Sometimes they will be in the mood to type the answer; sometimes they won’t. Either way, the program allows them to continue their progress.

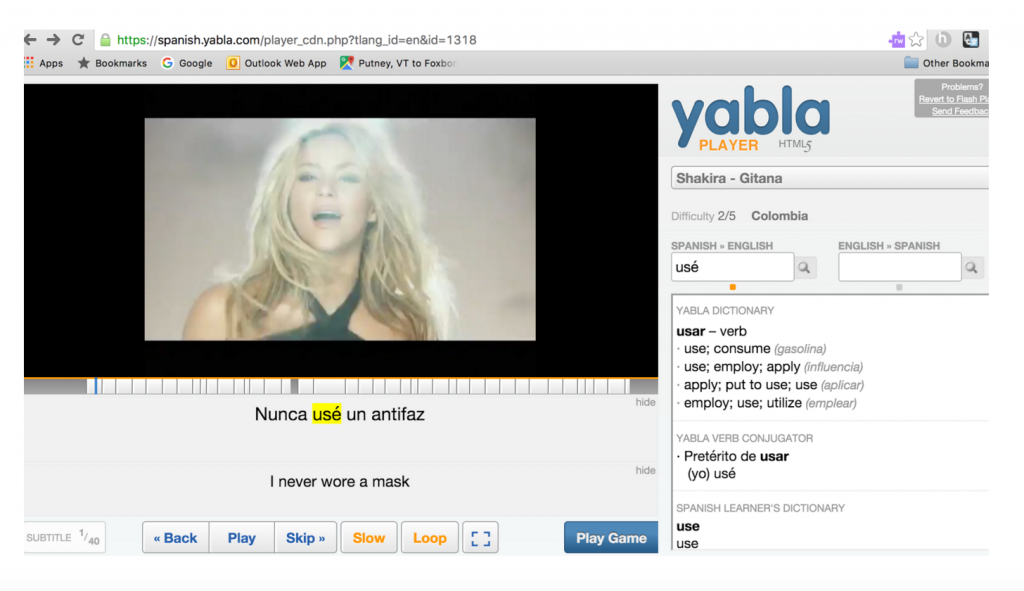

ACTIVITY STRUCTURED FOR SUCCESS: YABLA

Yabla, a video-based program, provides a number of impressive options that help users modify the experience. For example, a user can hide or reveal the text, slow down audio, and access a dictionary.

However, in the listening activity, many of my students are unable to hear and interpret the audio well enough to fill in the missing word. An added layer of resources (such as a list of words to choose from) would allow these learners to participate in the learning task more actively and with greater success.

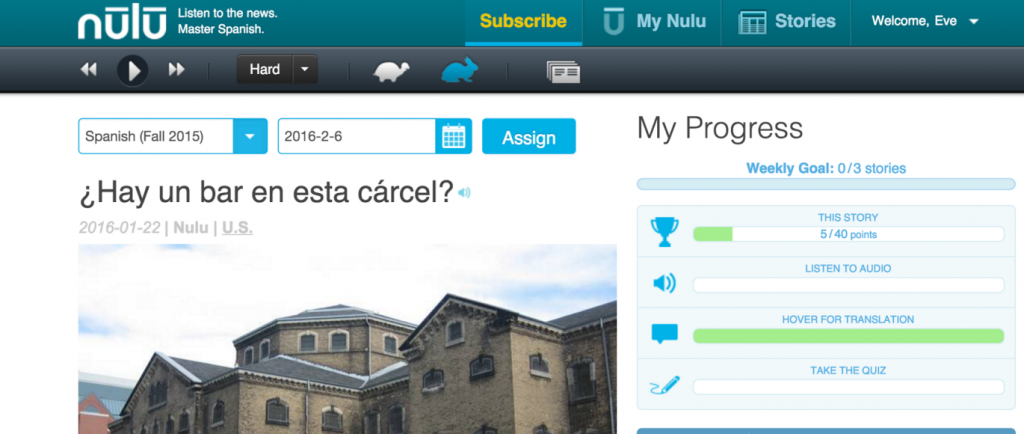

ACTIVITY STRUCTURE FOR SUCCESS: NULU

Nulu provides short, high-interest readings on a wide variety of topics. The stories are read by a human voice that can be slowed. If the learner hovers the cursor over a word, a translation appears. Three multiple-choice comprehension questions follow each reading. My students enjoy the Nulu format because it is structured and doable. They like having a choice of reading topics as well as sufficient support as they read. Comprehension questions can be repeated as many times as necessary.

SPECIFIC NEEDS AND SOLUTIONS

In this last section, I would like to highlight certain areas in which students may have specific needs for support: executive functioning, memory, reading, listening, writing and speaking.

Need: Executive Function Support

It is not uncommon for my students to have issues with “executive functioning.” That is, they tend to have difficulty with materials management, time management, setting priorities, meeting deadlines, and studying independently.

Solution: A number of practices are helpful in this area, many as fundamental as maintaining an organized class rich with routines and structure. A wealth of Apps are available to choose from, depending on the particular need. Here, I will focus on web-based solutions familiar to many teachers.

My primary resource in this area is my learning and course management tool. I find it indispensable for helping students keep track of assignments, deadlines, and practice materials. This is especially important for students who miss class and need to catch up. All links to practice materials can be easily found on my course page.

Equally powerful in terms of helping students set priorities and meet deadlines is an online gradebook. I use mine almost as an assignment book, listing assignments with deadlines and how much the assignment is worth. Students with learning differences, in particular, may not have an accurate sense of how they are performing academically. They may think they are doing much better or much worse than is the reality. Having easy access to their past, current, and upcoming assignments within a gradebook format can give students a clear picture of how they are doing and where they need to put their energy.

Need: Memory Support

Given the memory burden of learning a new language, all of our students, but especially those with learning differences, benefit from classes rich with memory aids.

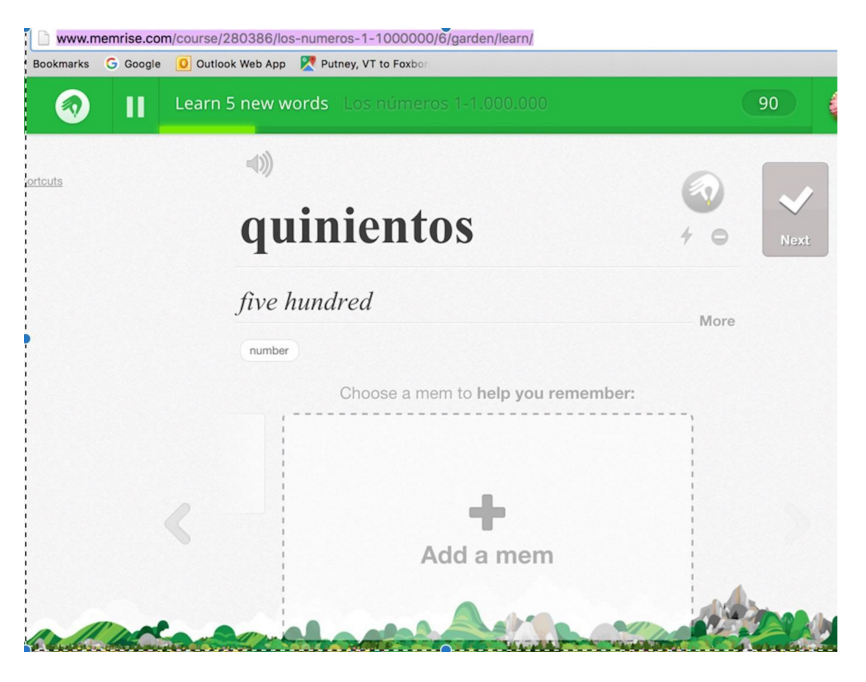

Solution: I strive to present information in ways that make it easier to remember, such as using mnemonics and integrating music and rhythm. These memory supports can be readily integrated into many learning practice materials. Memrise is an interesting tool for those who need specific memory support, although my students with ADHD have found the repetition tedious. I find Memrise especially interesting because you can choose a provided memory device or easily create your own.

http://www.memrise.com/course/280386/los-numeros-1-1000000/6/garden/learn/

Need: Support for Listening

Listening comprehension tends to be an area of weakness both for my students with language-based learning difficulties and for my students with ADHD. When I analyze materials, I look for structure, layers of multimodal input, student control, and rapid feedback. For example, at minimum, does a video provide closed captioning? Is the sound quality acceptable and free from background noise?

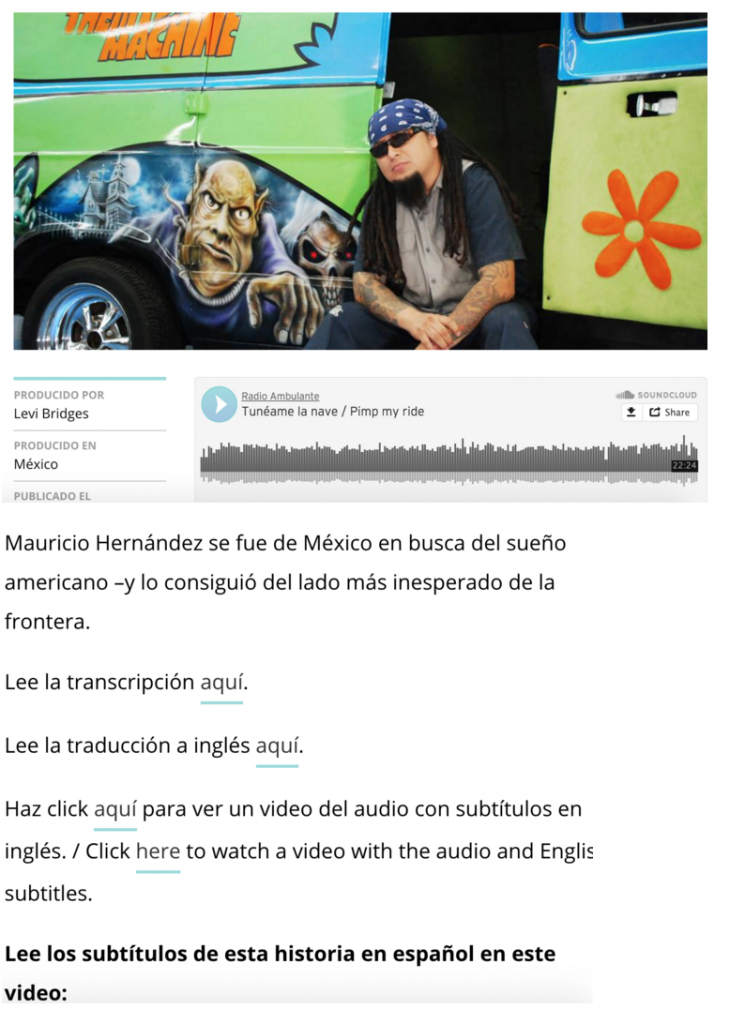

Solution: One example of high-interest supported listening for my upper level students is Radio Ambulante, a thought-provoking Spanish language podcast that tells compelling and uniquely Latin American stories. Not all stories have the same number of supports, but some provide access to audio of the story in Spanish, the written transcript in both English and Spanish, and a video that includes the audio with the written text in Spanish. Even with these augmentations, my students prefer more visual content to aid comprehension and focus. I add vocabulary practice, discuss reading and listening strategies, and chunk the content into smaller segments. The shorter pieces are perhaps most manageable. Adding additional layers of interaction with a program helps students stay focused. A program like Zaption could be used to add comprehension questions, for example.

http://radioambulante.org/audio/tuneame-la-nave

High interest listening piece with written text provided in multiple forms.

Need: Support for Reading

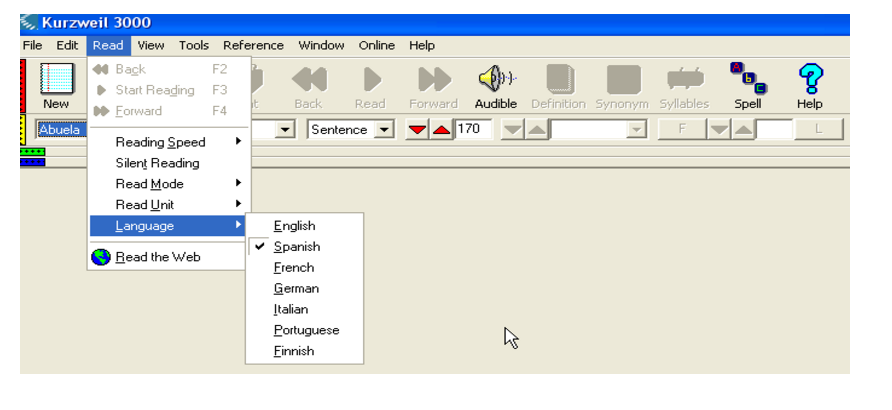

Students with language-based learning differences are likely to struggle with decoding and reading. Students who are blind or have low vision will need unique modifications.

Solution: While some students with reading disabilities will be supported sufficiently by being able to enlarge text, choose a sans serif font, and access pronunciation assistance as needed, others will benefit from text-to-speech programs. Two such programs, Kurzweil and Voice Dream, offer students a variety of tools to aid in comprehension of written material. Each is available in a number of languages. VoiceOver (with multilingual text-to-speech options) was integrated into Mac OS X. It may be useful to note that some learners have a hard time adjusting to the synthetic text-to-speech voices. Students with vision challenges may require electronic magnification tools, the ability to manipulate font, and text readable by a screen reader such as JAWS. Please note that e-textbooks written in JAVA will not be readable by text-to-speech programs. Ask publishers if their materials are “screen-readable.” VitalSource is a good resource for accessible texts.

Need: Support for Writing

Written output can challenge students for a wide variety of reasons, including difficulty generating ideas, organizing thoughts, spelling, proofing, and (for some) difficulty typing or writing by hand.

Solution: Students benefit from a host of support tools, such as “Inspiration” to help organize their ideas and speech-to-text programs such as those built into their devices or Dragon Naturally Speaking to help generate writing. Text-to-speech programs such as those mentioned earlier and Voice Dream Reader can be useful for proofing. Students should also have ready access to standard resources such as spell check and online dictionaries.

Need: Support for Speaking

Oral output can be challenging for students who have language retrieval issues and those who are slow processors. Other students may have specific issues with pronunciation.

Solution: Students with learning differences generally benefit from advance preparation. I give them opportunities to write down what they want to say first, by hand or on the computer, and then use that writing/brainstorm session as a starting point for conversation. Practicing conversation through texting/chat can also be fruitful, as it takes language production slightly out of real time.

CONCLUSION

Thoughtfully designed web-based language practice materials can go a long way in offering critical elements of support for our neurodiverse students with a variety of profiles, including language-based learning differences, ADHD, and autism spectrum disorder. Designed with an eye to the elements I have outlined in this article – learner control, rapid feedback, interactive and multimodal design, multiple practice formats and structures to promote successful learning – these tools are powerful and effective. Since no one size fits all, it is wise to take advantage of programs offering simple authoring tools that make it easy to modify and individualize content. While students need routines, they also appreciate novelty, so a varied toolbox is essential. Perhaps the most important task is to create a learning environment where students feel comfortable, capable of the task at hand, and able to witness their progress.

When queried informally about what they wanted most from web-based language learning, my students responded: fun, interesting, multimodal, easy-to-use programs that give feedback in real time, accessible on their devices. Asked what sort of language learning program they would design for themselves, students suggested a virtual computer partner, or a computer designed to converse with you and give you instant feedback on your language usage. Another student suggested something that would let you borrow the brain of a native language speaker when you needed it. One student summarized the benefits of language learning technology like this:

“As a college student learning a foreign language, the use of technology has been vital to my success. I can devote extra time outside of class in order to learn extra skills that the amount of class time did not allow us to learn. I believe that technology use is a vital piece of the puzzle that is learning a foreign language.”

I teach because I want students to have the confidence to use their new language in real-life situations as a means to connect with others, a door to new ways of learning about and experiencing the world. At the end of last semester, I was delighted to received this text from a student heading home to California:

“I’m getting my new car checked out in Hartford and the business guy isn’t here – just the one mechanic… and he speaks not a word of English! Pero…digo cambiar el aceite y cambiar coolant y inspección general. ¿En una hora? Porque tengo un vuelo a tres. ¿Listo para invierno? ¿No necesita nada? ¿Cuánto cuesta? It’s so cool!! I’m excited for next semester = above and beyond.”

In this snippet, the students asks the mechanic to change the oil and the coolant and complete a general inspection. He follows up with, “In an hour? Because I have a flight at 3. (Is the car) ready for winter? Is doesn’t need anything? How much does it cost?” This short conversation illustrates how what we teach has personal applications outside of the classroom. The student took what he learned in class and reconfigured it to meet his needs. His excitement and pride were evident. This was a student who had been struggling academically all semester. In the end, he did miss his flight that day, but he is continuing his language learning, loves to text in Spanish, and always asks for more web-based practice homework.

REFERENCES

Leons, Eve. “The Learner – Diverse and Differently Abled: Understanding the Learning Journey.” The Language Educator 8, No. 4 (August 2013): 32–34.

Leons, Eve, Christina Herbert, and Ken Gobbo. “Students with Learning Disabilities and AD/HD in the Foreign Language Classroom: Supporting Students and Instructors.” Foreign Language Annals 42 (Spring 2009): 42–54.

How can I teach my self a foreign languages with apd ,are there any techniques or strategies for self learners to process the words out loud ? Thank you and god bless

Thank you so much for this resource. I’ve been a Spanish teacher for 19 years and I’m looking for ways to reach my neurodiverse learners. So many kids at my school who have diagnoses of dyslexia can still learn and still benefit from my class. I appreciate the mention of EF difficulties as well, and how you can mitigate those. What a great resource!

Thank you so much for this resource. Wish I’d looked for this sooner. My son is 16, yslexic, with APD and on the autism spectrum.

He is having a very difficult time with Spanish, so I

I’m hoping that some of these resources will be helpful for him.