The Benefits and Challenges of Spaced Repetition Flashcard Apps for Language Classes

By Richard Cozzens and Eric Bartolotti

DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.69732/BJCY4071

In this article, we discuss the concept of spaced repetition study (SRS) for language learning and introduce two useful “smart flashcard” apps available for learners and teachers: Anki and Mochi. While the concept of spaced repetition – reviewing learned material intermittently over time – is familiar to learners and teachers, we have found that when we talk to our students and colleagues about the tools for systematic spaced repetition, they find the concept and practice quite unfamiliar and challenging to customary study habits. We will make our case for using spaced repetition apps for language learning and describe our experiences in promoting these tools with our classes. We hope that by the end of the article you will know more about the benefits of SRS apps and the challenges to implementing them as a classroom tool.

We approach these topics as language learners who have extensively used SRS tools ourselves, but also as language teachers who have promoted this method and these tools with our students. When Eric taught Arabic at a high school in Massachusetts, he had his students use and create flashcard decks using Anki; Richard, currently teaching introductory Arabic at Harvard University, has been providing students with course Anki decks and encouraging their use for the past few years.

“Smart flashcards” — an SRS user experience overview

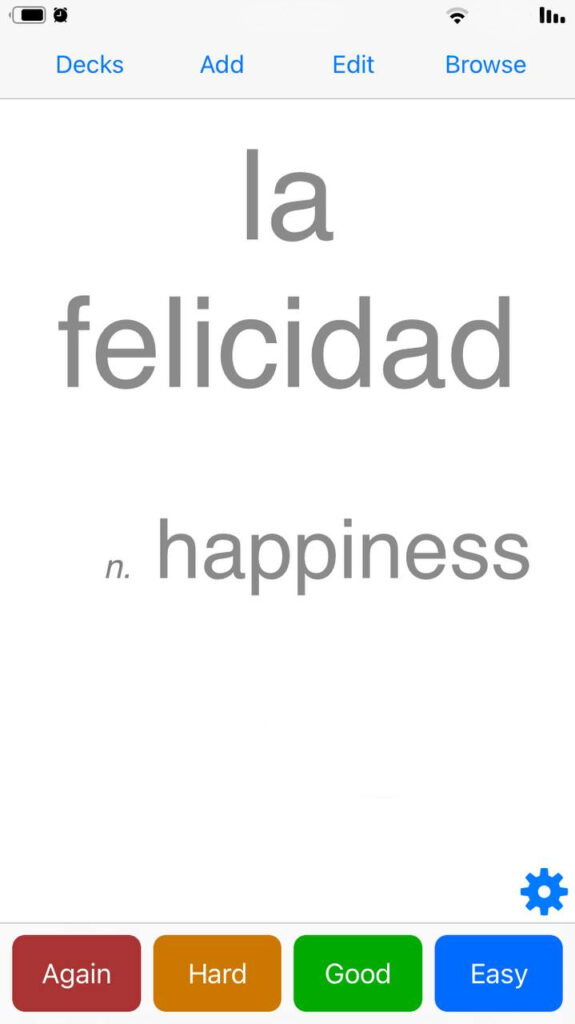

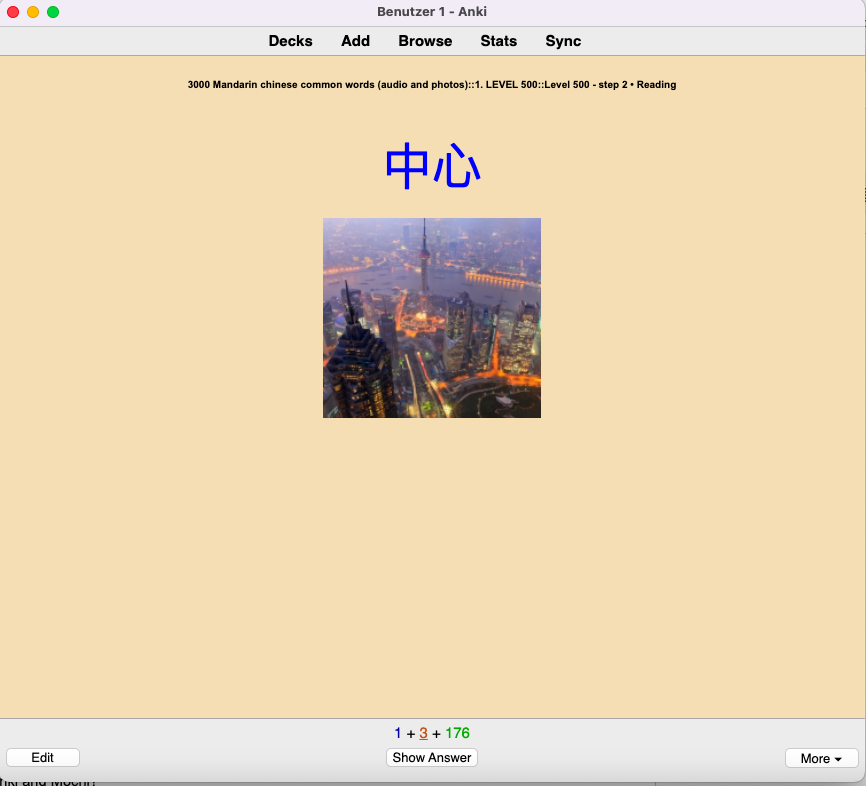

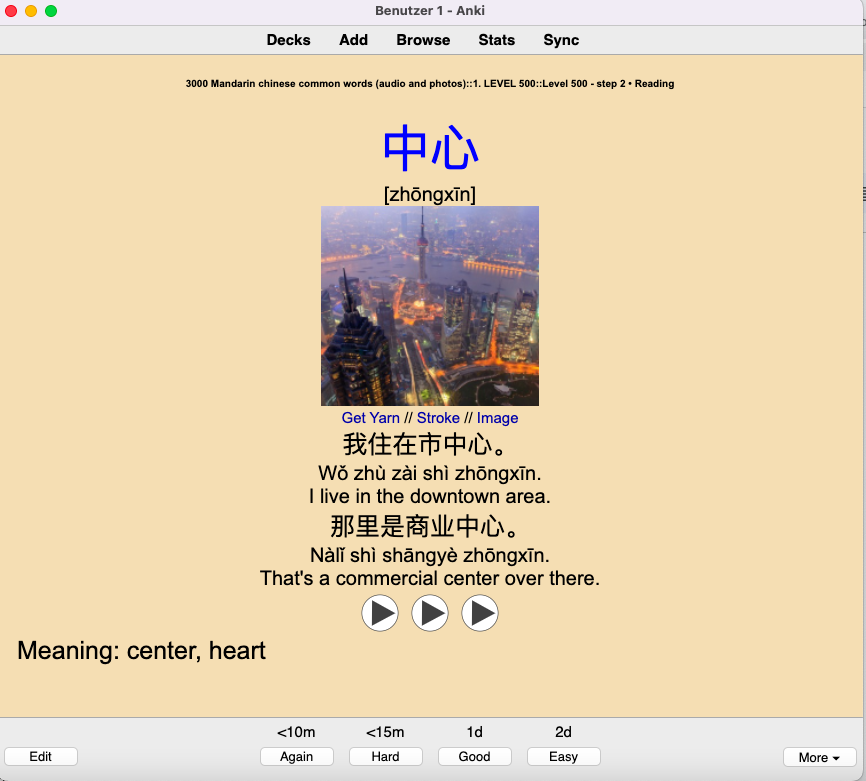

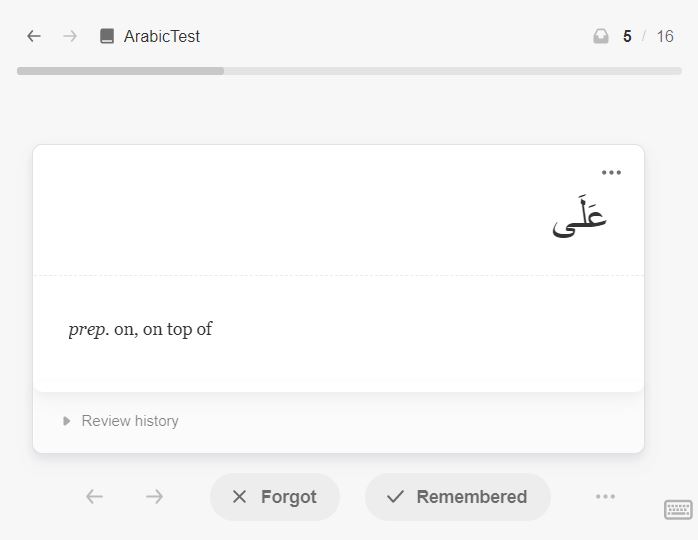

Before we go further into benefits and challenges, we think it would be helpful to describe what it is like to use SRS flashcards. When using your flashcard application, you are presented with cards that are “due” for you to review on a given day. For each card, you look at the “front,” check your knowledge of that item, and then click on a button to reveal the “back” or answer of the card.

Upon seeing the back of the card, you tell the program whether or not you remembered the card. If you recall the meaning of the item, you will click on “Hard,” “Good,” or “Easy,” which will tell the program to increase the interval after which you will see that card again. If you forget the meaning of the item, you will click on “Again” which will decrease the interval until you are next shown the card. Thus, cards that are easier for you will appear progressively less frequently as your memory of them grows stronger; cards that are harder for you will appear more frequently to help you strengthen your knowledge of them.

In what follows, we will discuss what we see as the main benefits of SRS apps and the challenges that come with using flashcard tools in the language classroom.

SRS is more efficient and effective for retaining material …

For more than 100 years, research has proven the effectiveness of spaced repetition study as superior to massed practice (i.e., “cramming”) for learning information and skills for the long term. Learners who are exposed to – and tested on – material in study sessions that are spaced out over time remember more of that material than learners who spend the same amount of total time in a single study session, and this finding has been proven repeatedly and consistently (Kang, 2016).

The promise of an SRS app is that it is adaptive to an individual: learners do not waste time studying what they know well and thus spend more time with what is difficult for them. In a 2019 study asking students in a first-year Spanish class to use Anki with a pre-made deck of cards, researchers found that time using Anki had a positive relationship with improvement in Spanish level during the semester of use, while controlling for baseline abilities, motivation, and other variables (Seibert Hanson & Brown, 2019).

… but it challenges customary study habits

We believe that the main obstacles to adopting SRS are from conventional classroom habits and structures. In our experience, most classrooms in schools and universities – even those taught with alternate teaching methods – are still structured around high-stakes tests on discrete chunks of material (such as textbook chapters). Such structures encourage learners to cram information and not return to it once the test has passed.

Another challenge when introducing SRS is that using the flashcards requires some self-evaluation. The user must decide, “do I know this piece of information?” after looking at the back of the card, and they must respond honestly for the program to work well. We have found that students are used to a teacher or a computer telling them whether they are right or wrong, and they initially find this kind of self-monitoring to be unfamiliar.

Along similar lines, the benefits of SRS flashcards are dependent on the user maintaining a habit of using the program regularly, ideally every day. We have found that many students struggle to build such a habit because it does not match how they are used to studying and the benefits are not immediately tangible; they accrue over time.

Our anecdotal observations are confirmed by the 2019 Anki study: despite the researchers’ requiring Anki use as part of a homework grade, a majority of students did not use the program, and only a small minority used it regularly (Seibert Hanson & Brown, 2019). When I (Eric) used Anki with my high school students, they would usually only open Anki on the three school days when they had class (and never on the weekend). This sparse study schedule slowed their progress, which led to frustration and, over time, even less frequent use of the program.

When introducing Anki as a study tool, I (Richard) required students to submit a screen-shot of their Anki usage statistics as part of a weekly journal-like assignment that I had separately assigned to them that was part of a homework grade. In essence, I tried to use the existing system of carrots and sticks (completion grades) to encourage building a habit around Anki. This was nominally successful in that it led many students to use Anki; however, the fact that it was required meant that the motivation for using the program and building vocabulary remained extrinsic and not intrinsic. Indeed, most students stopped using Anki after it was no longer required.

When giving feedback on using Anki, some students who adopted the habit praised it as an essential tool for their language development, while other students rejected it. It seemed that for some students, requiring a “habit” of them felt like an invasion of their personal autonomy. Perhaps a process-oriented requirement like spaced repetition study is seen as outside the usual range of things that can be required of students: products such as homework assignments, papers, or tests.

These experiences suggest the importance of conducting repeated discussions with students about the rationale behind using spaced repetition tools and their potential for building lasting memories, in conjunction with discussions about language acquisition and students’ goals. These discussions can help students develop a new concept of long-term language growth that can build intrinsic motivation for studying.

Our experiences also suggest the potential value of making the habit of spaced repetition motivated through means other than grades, perhaps through gamification. SRS tools are particularly well suited to gamification due to the extensive statistics these programs provide. The teacher can set goals based on these statistics for the students, or require students to set goals for themselves. Depending on the classroom dynamic, the teacher can choose to have these goals be individual, collaborative, or competitive. For example, you could present a “leaderboard” with the students who have the longest daily study streak, or you could make a collaborative “class goal” of SRS usage. If you are short on ideas, you can always try researching what games are popular with your students and use them as models.

SRS is supportive of language acquisition …

In our view, SRS is especially appropriate for language acquisition. In this view, we are following scholars and practitioners who emphasize the central role for communicatively embedded input for second language acquisition (Lichtman & VanPatten, 2021). Exposure to large quantities of input, in itself, provides spaced and repeated exposure to most common elements (words, structures, etc) of a language. In other words, one cannot “cram” language acquisition by definition; it develops on its own through repetitions over time.

The idea with deliberate SRS tools is that they use an algorithm to systematize exposure to language elements, make the process more efficient, and adapt to an individual learner’s strengths and goals. While many existing descriptions of SRS for language acquisition are directed at independent learners (as exemplified by the Refold Method and online community), we believe that SRS flashcards could form an important supplement to institutional classroom teaching practices and push us towards practices that support acquisition for the long-term.

SRS programs are especially well-suited for building and maintaining vocabulary knowledge, an aspect of language learning that we think is often not emphasized enough in classrooms. Many conventional language syllabi are structured around grammatical concepts of increasing complexity, rather than prioritizing the most frequently used words. We believe that gaining baseline familiarity with the most common vocabulary items of a language can give students the capacity to make sense of and learn from authentic texts sooner in their learning process.

… but it cannot work all alone

Rote memorization of vocabulary is a lower-order skill that itself does not guarantee language acquisition; this may make some teachers reluctant to promote it, or they may consider vocabulary learning as a task that students can manage on their own. In our observation, the students that have the capacity to understand more words are more quickly able to progress towards higher-order skills with language, and our students who use Anki regularly have found it very helpful. That being said, SRS study of decontextualized vocabulary items is certainly not enough on its own – students still need to apply other study strategies such as developing their own mnemonic devices and practicing words in context. While SRS applications are not a total solution, we believe that teachers should promote any tool that allows students to be more efficient and effective in their studying of an essential component of language learning.

SRS apps are customizable and feature-rich …

While vocabulary learning is the most common use of SRS applications, they can also be used to practice vocabulary in context (flashcards with complete sentences) and listening comprehension (flashcards with audio clips). The SRS apps described here are extremely feature rich: in addition to all kinds of media integration, they contain templates for cloze tests and reversible cards (where the “question” and “answer” fields are automatically reversed).

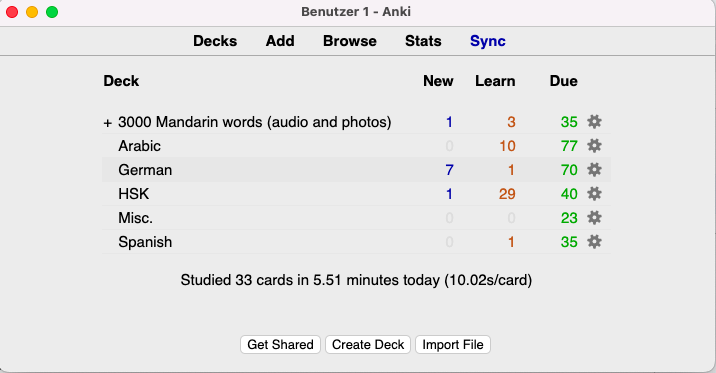

Learners can track their studying with the “statistics” feature of the apps; cards can be grouped via tags to emulate the themed vocabulary lists of textbooks that students are familiar with. When I (Richard) have used an SRS application with my classes, I have created custom decks of flashcards for my students based on the standard course materials, ensuring a streamlined experience for students.

… but the complexity of the tools can be intimidating

While customizability is a defining feature of SRS apps, this comes at the cost of complexity. In this era of extremely user-friendly app interfaces, students and teachers often find the complexity of the apps to be intimidating or even prohibitive. Teachers who wish to have their students use an SRS application will first need to become familiar with the application themselves, so that they can guide their students to use it well. While I (Richard) appreciated the capacity to customize a deck for my students using Anki, there is no doubt that I worked hard on this and had to read some of the fine print of the extensive user manual!

Using SRS promotes independent and self-paced learning …

We believe that one of the most compelling reasons to encourage students to use an SRS application is that it promotes independent and differentiated learning habits. Terms such as “independent learning” and “differentiation” can become empty buzzwords when our syllabi are designed around textbook chapters and our assessments are quizzes and tests that expect all students to be progressing at a uniform pace. With their adaptive algorithms, SRS applications have the potential to offer level-appropriate support and challenge to students at different levels in a single class. More importantly, we hope that teaching students how to use a tool well-suited for independent learning will increase their chances of continuing with language study beyond the institutional context.

… but this can feel disconcerting

For many students and teachers, the adaptive nature of an SRS application can be bewildering at first, since it relies on a conception of learning that is in contrast to the “present–practice–test” mode of conventional language classes. I (Richard) found that many of my students reacted initially to using Anki as a disconcerting loss of control, since they couldn’t see a whole “list” of words and items seemed to appear haphazardly. The SRS algorithm, by definition, reschedules items according to user mastery, an operation which challenges the sense of control (and capacity for assessment) that a delimited word list offers to students and teachers. Students in the Anki classroom study complained that the app had them “studying words from chapters they had already been tested on” (Seibert Hanson & Brown, 2019, p. 145). In other words, the main feature of SRS was seen as a drawback because it did not serve students’ desire to learn (“cram”) for the test!

In order to mitigate this challenge of adopting a spaced repetition tool, we recommend regularly offering students the opportunity to share their experiences with SRS, in the context of discussions about language acquisition, long-term learning, and strategies to overcome frustrations or difficult feelings. I (Richard) encouraged my students using Anki to share about their experience in the journal-like assignment that they did, and I also held periodic open discussions in class to give students a chance to share their experiences – and for me to understand what was difficult and how those difficulties could be addressed.

We recommend making these discussions a regular part of a class that incorporates SRS tools, even more than we were able to. Because of the unfamiliar nature of spaced repetition study to many, it will take time for students to understand the rationale behind spaced repetition and its value. Teachers could present summaries of research about the nature of language acquisition, discuss the importance of building vocabulary in the long term, and connect these topics with student goals for learning a language. Discussions could also include reflecting on the nature of learning and education more broadly. While some students may be interested only in working for the grade, others will welcome the chance to discuss and think more deeply. This could include acknowledging the difference between grades (an assessment of student work expected by the institution) and learning (an investment in one’s self that will take time to develop). Some students ask the infamous question “When am I going to use this?” and want a truthful answer. Rather than wait for students to ask it, we can proactively provide an answer. Fortunately for world language teachers, the practical uses of knowing a foreign language are very tangible. Offering a forum for students to ask and consider these questions will help them develop their own understanding of learning and find their own motivations.

Review of SRS Flashcard Apps

In reviewing flashcard apps, we have focused on programs that 1) are designed primarily for spaced repetition, 2) are customizable, 3) are available cross-platform, and 4) offer freely available versions.

When most people think of flashcard apps, they think of Quizlet. While Quizlet has the benefit of being very easy to use and user friendly, it no longer offers spaced repetition study, as it discontinued its “Long Term Learning” feature in 2020. Duolingo, the most popular language learning app, similarly abandoned its flashcard spinoff, “Tinycards” the same year. While Duolingo still uses the concept of spaced repetition in its lesson design, it is effectively a closed system, ie. users cannot add study items of their own or otherwise tailor their experience.

We have focused our review on Anki and Mochi, both of which fit the criteria listed above. Other available SRS programs include SuperMemo (the original SRS, but it only offers a paid option) and Mnemosyne (totally free, but does not offer applications for all platforms).

Anki

Anki is one of the oldest, most well-known, and most powerful SRS apps. It is free for desktop computers, web browsers, and Android phones. The developer offers an iOS app for a $25 one-time fee (“AnkiMobile Flashcards”) though it is possible to use the browser-based version from an iPhone browser for free. Anki offers free synchronization of flashcard decks between devices. Anki also gathers a large collection of user-created, shared decks for many languages available for download. Creating Anki cards is best done on the desktop version; while making simple front-back cards is easy enough, the impressive array of options and features can be quite overwhelming for new users. Some of our students have found Anki’s visual interface to be “old-fashioned” to the point of being unappealing, but recent updates to the desktop Anki program may alleviate this critique.

Mochi

Mochi is representative of a number of new SRS apps that prioritize aesthetics and ease over intricacy, while still touting many of the same flexibility and features of Anki and other older SRS apps. It is free for all platforms but synchronization between devices costs $5 per month. The shared decks gathered on the Anki website can be imported to Mochi, though sometimes formatting problems result. A distinguishing feature of Mochi is the minimalist design and simple interface, which a number of our students experimented with and highly praised. Creating cards can be done through any of the platforms and is relatively simple and text-based, while still incorporating media integration. The fact that Mochi offers fewer settings and options than Anki is probably a plus for most student users of SRS apps who are pressed for time.

Conclusion

We believe that we teachers should educate our students about the extensive repetition (recalling and forgetting) that is necessary for true language acquisition and supply them with helpful tools and practices to make this possible and easy. SRS apps like Anki and Mochi provide one way to do this as a supplement to other language class activities, offering students a learning tool that can extend beyond the quiz, the final exam, and the academic year. We believe that the primary challenges of using these flashcard apps – dissonance with the conventional syllabus, apparent complexity, and expectation of a daily habit – are analogous to the challenges inherent in inspiring classroom students to work towards long-term language acquisition. We encourage teachers to face these challenges alongside their students.

References

Kang, S. H. K. (2016). Spaced repetition promotes efficient and effective learning. Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 3(1), 12–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/2372732215624708

Lichtman, K., & VanPatten, B. (2021). Was Krashen right? Forty years later. Foreign Language Annals, 54(2), 283–305. https://doi.org/10.1111/flan.12552

Seibert Hanson, A. E., & Brown, C. M. (2019). Enhancing L2 learning through a mobile assisted spaced-repetition tool: an effective but bitter pill? Computer Assisted Language Learning, 33(1-2), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2018.1552975

Quizlet seems to have the spaced repetition integrated again as well: https://quizlet.com/features/spaced-repetition

Je viens d’utiliser quizlet en février sur plus de 80 questions et la répétition espacée n’a pas l’air de fonctionner. D’une session sur l’autre, seules les cartes auxquelles on n’a pas répondu reviennent. Dès qu’on a bien répondu à ces dernières, toutes les cartes reviennent. Quizlet dit qu’il l’utilise mais au lieu d’expliquer son fonctionnement, part sur d’autres sujets.

Merci en tout cas pour cet article.