Reflecting in a Digital Space: Capturing Student Experiences While Abroad

By Sherry A. Maggin, Zachary F. Miller, William E. Choate, The United States Military Academy

DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.69732/EPSZ3205

Language immersion experiences can be an opportunity for significant gains not only in language skills and cultural awareness, but also for personal growth and reflection. Various programs have explored the benefits of providing students with the opportunity to document and reflect on the immersion experience as part of a university course or as personal development. Some common approaches for guiding reflection are e-journaling, blogging, digital storytelling, and map making. This article will discuss the evolution of one college program’s approach to capturing student reflection during short and long-term immersions through digital book creating and map making projects. We will present the components of the United States Military Academy’s distance-learning study abroad course, the changes made to incorporate technology and different media through various iterations, and how we have extended the model to other immersion experiences. We will also discuss the value of digital book creating and map making and how these approaches can facilitate interaction among students, encourage interdisciplinary collaboration among different academic departments, and allow language programs to recruit and motivate future language learners.

Students participating in a semester abroad through the Department of Foreign Languages (DFL) at the United States Military Academy (USMA) may enroll in a semester-long, distance-learning course entitled Advanced Language and Culture in Context (LN451). Though not required, this three-credit hour course is routinely taken by students studying abroad with the Portuguese and Spanish programs in addition to the courses they take at the host institution. Grounded in the principles of Open Architecture Curricular Design, the course emphasizes student-directed learning and critical reflection. Students complete a series of weekly reflections and other related essays or task-based projects throughout the semester. For the weekly reflections, students are free to select from a topic list and complete an essay each week or they may propose their own topic for reflection based on their current experiences. This flexible approach allows students to choose topics that align with their authentic immersion experience rather than only relying on top-down, teacher-driven assignments. Examples of self-reflection topics include:

- Articulate any personal and professional goals during your semester abroad.

- Attend a cultural event/activity. Provide a brief description of the event and discuss your assumptions/expectations prior to the activity. Reflect on any impacts to these assumptions/expectations afterwards.

- Discuss a major news event/topic with some of your acquaintances and learn more about this issue from local media sources. Describe the issue in detail, including observations from your conversations and the media.

This course has always utilized technology to facilitate communication and assignment submission. In past years, students traditionally completed these purely text-based reflections in a Word document and emailed them to their instructors. However, in recent years (2019-present), we have recognized the need to incorporate more opportunities for students to enrich their essays through photos and other media and to document their experiences beyond a simple Word file (Gabaudan, 2016). Thus, the course has evolved well beyond a traditional Word document format and now includes digital book creating and map making projects. These new versions allow for more interaction with language and culture and more creative expression for the students.

Documenting the Immersion Experience through Book Creation

In the fall of 2019, the Spanish version of the course transitioned to digital scrapbooks, utilizing the Book Creator platform. Book Creator is an online platform where instructors and students can read, create, collaborate, and publish digital books using a wide variety of media and design features. Students enrolled in the study abroad course use the platform to create a digital scrapbook of essays, photos, drawings, and other media that documents their semester abroad experience. Students personalize their book from the very beginning by choosing the shape of the book and the background and format of each page. For each weekly topic they select, students create entries in their scrapbook, which include three paragraphs of text in the target language and 2-3 personal photos or videos. In addition to nine weekly topics, students also create entries for military training reflections and catalog new words or phrases they learned during the semester in a vocabulary collection at the end of their digital book. Once ready for final submission, students share their books with instructors and fellow semester abroad participants through one of the publication options. Students are required to read and comment on each other’s books as the final assignment in the course.

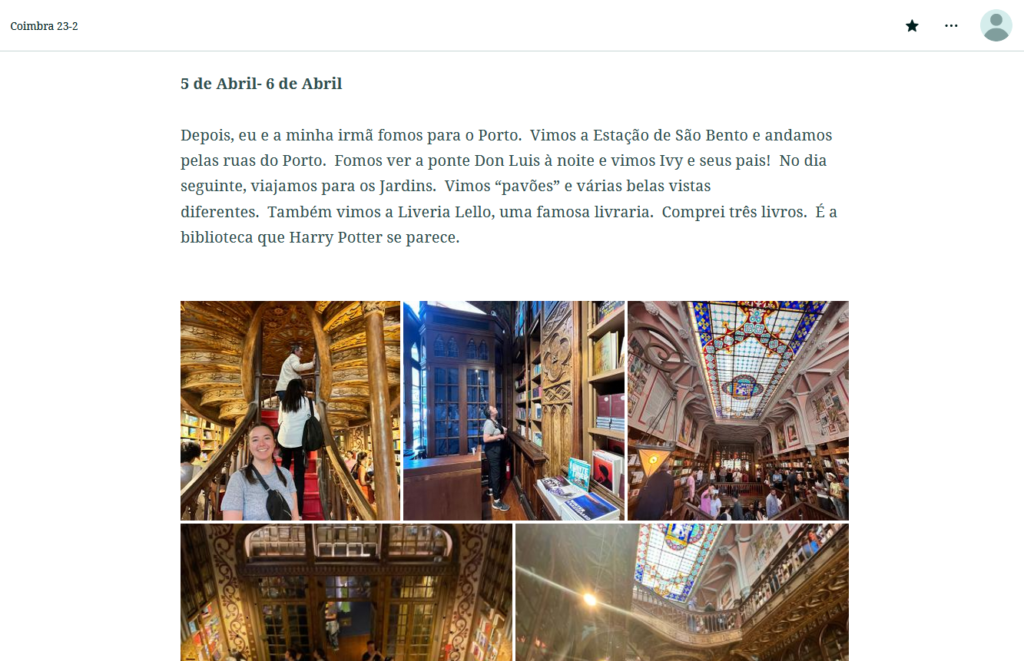

There are many benefits to updating the course to incorporate digital book creation as a method of documenting the study abroad experience. Importantly, students can design a personalized account of their time abroad by exercising creativity and reflecting on their experiences using a journal-type structure (Stewart, 2010; Schenker, 2021). Students can complement their written reflections by adding personal photos and videos, creating cohesive pages in a digital scrapbook. In general, most students incorporate personal photos and photo collages from their semester, including selfies, pictures of classmates, interesting places around the city, food, and the like. Others add short videos of cultural events or activities to accompany their reflections.

This personalization and flexibility allow students to document and share their unique study abroad story. Students are also able to express their creativity by recording a narration or drawing directly onto the pages of their books using the pen function. One student even exercised their creativity and artistic flair by drawing in various parts of the book like on the title page above and in the vocabulary collection to better showcase and communicate their reflection.

A final benefit is that students have a ready-made memento of their travels to share with others (Schenker, 2021), including with one another. Through reading and commenting on each other’s books, students potentially gain different perspectives on similar experiences and are able continue interacting with each other after the immersion experience has ended. Additionally, students often download a copy of their book or share it with family and friends by publishing it to the web or downloading it. A potential drawback of this approach is the loss of media when the book is downloaded in certain formats like pdfs. Another drawback is that students sometimes encounter difficulty when writing in a foreign language in Book Creator. However, overall, most students have provided positive feedback on the project and appreciated having a product that captured their semester abroad experience.

Documenting the Immersion Experience through Map making (Iteration 1)

As an alternative method of journaling for those enrolled in our semester-long study abroad course, the Spanish program joined the Portuguese program in a new map making approach to reflection. We asked students attending military academies in Chile, Brazil, and Portugal to capture cultural activities, including any associated perceptions and reflections, in an online mapping system. We called this space, which was powered by Esri’s ArcGIS Survey123, the Geocoordinate Recording and Experiential Activity Tracking (GREAT) platform. This joint venture between the Department of Geography and Environmental Engineering (GEnE) and the DFL allowed students to pin event locations onto a map and archive their immersive experiences within a digital space. This approach added spatial and geo-tracking elements to the course design and provided students with an opportunity to better catalog and potentially share their journeys abroad (see Stewart, 2010; Urlaub & Dessein, 2022).

Assessments in this iteration of the course consisted of (1) essay submissions and (2) experiential activity uploads. Due to length and formatting requirements, we allowed students to complete longer written assignments (e.g., initial reflective essay, experiential activity deep dive, and final reflective essay) using Microsoft Word, which they submitted via email. We also required students to participate in and record nine experiential learning activities events on the GREAT platform. Students had to select at least one activity from each of the following six categories:

- CULTURAL PERSPECTIVES (e.g., attending a sporting event, visiting a local festival, watching a movie in a local movie theater/cinema, etc.).

- LIFE AT THE MILITARY ACADEMY (e.g., highlighting barracks life, military training, your daily routine, academic classes, etc.).

- SOCIAL PERSPECTIVES (e.g., eating at a restaurant, attending a social event at a friend’s house, etc.).

- HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVES (e.g., visiting a museum, a church, monuments and/or historical sites, etc.).

- GEOGRAPHY AND THE PHYSICAL SPACE (e.g., exploring local parks and green space around your host city, nature reserves, beaches, mountains, etc.).

- USING PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION (e.g., using subways, trollies, rideshares, etc.).

Within the GREAT platform’s submission page, students first dropped a pin on the map to designate where the activity occurred. Next, they provided a 300-word description of the event in the target language. We recommended that each story highlight any prior assumptions, unique encounters, and post-activity reflections (Dessein & Urlaub, 2020; Urlaub & Dessein, 2022). Lastly, students uploaded four photos associated with the experience onto the platform. In keeping with the overall approach to flexibility in the course, there was no designated order in which to complete the activities. Students were only required to upload their final products onto the GREAT platform prior to the prescribed deadlines.

After two semesters of using the GREAT platform for digital map making and journaling, we identified both positive and negative aspects of the program. The main benefit was our ability to create an interactive product similar to popular commercial photo sharing and mapping applications like Instagram, Google Maps, and All Trails. Aligning our platform with current technology was important for us to boost user motivation and keep the assignments relevant to our students (Godwin-Jones, 2016). While participants could not share their pins with others outside of the platform, all participants could see one another’s pins, and we discovered additional valuable, internal uses for the finished product, such as recruiting future study abroad participants and foreign language majors.

Regarding limitations, as opposed to other versions of the course, all experiential activities were restricted to specific prompts (i.e., our six categories) as designated by the course director. Although students maintained a level of flexibility in choosing their own activities, pins were not created organically or spontaneously. In addition, the technology of the GREAT platform was not conducive to inputting longer text, displaying larger photos, or adding video content.

Documenting the Immersion Experience through Map making (Iteration 2)

In addition to using ArcGIS for the GREAT platform during study abroad, we recently began using the ArcGIS’s StoryMaps application for digital map making and journaling during study abroad as well as other, shorter immersion experiences that leveraged the course’s reflection tasks and technology integration. In comparison with the previous version of map making, the StoryMaps tool from ArcGIS has provided an improved, user-friendly experience for our cadets and instructors.

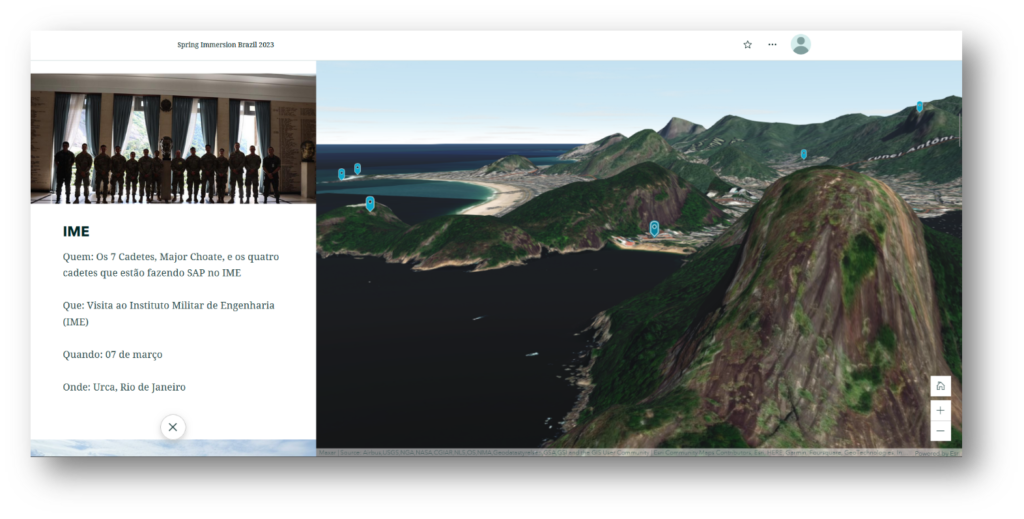

For short-term experiences, we asked students to build a StoryMap either during the trip or immediately upon their return. Our first iteration involved a three-week immersion trip to Brazil. In this iteration, the students and instructor collaborated to build the StoryMap at the end of the visit as a post-immersion reflection activity. As seen in Picture 3, the StoryMap has 2D and 3D pictures that provide stunning and realistic visuals of the terrain. Additionally, as Picture 4 shows, StoryMaps allows the user to link photos and text to points on the map through tools like the Explorer Map tool. The second iteration occurred during a one week immersion trip to Brazil. Students were tasked with recording details of each event during their week in Rio de Janeiro. Subsequently, we asked them to share with their classmates in our basic Portuguese course about their trip abroad using their ArcGIS StoryMap. In this manner, students built, curated, and shared their StoryMaps product, highlighting their linguistic and cultural experiences in Brazil. This had the added benefit of not only allowing the students to showcase their new expertise in language and culture, but also of potentially increasing student interest in the Portuguese program.

Though not enrolled in the study abroad course, students participating in the Portuguese study abroad program used StoryMaps this year to submit weekly reports through creating multimodal texts. Picture 5 displays a selection of weekly updates from our students studying abroad in Portugal. These reports gave students the opportunity to journal about their weekly experiences and simultaneously helped the study abroad coordinator monitor students’ language proficiency and provide feedback. This endeavor was facilitated by our ability to create a “Group” in ArcGIS. For our department, the Group feature demonstrates the potential for both active and passive program advertising. For example, while we asked students to actively create and brief StoryMaps stored in the group, other students using the program for geography classes may also come upon our creations and immersion experiences as they prepare their own mapping projects and take time to view the StoryMaps of the students studying abroad.

The evolution of Esri’s software and the creation of the ArcGIS StoryMaps tool enhanced our digital map making and journaling efforts and is a program we will continue to use during both short and long-term immersion experiences. Our experiences with the tool for digital map making and journaling over the past year have motivated others in our department to expand their own programs. For example, the Chinese and Russian programs recently created groups similar to the one mentioned above into their immersion programs. Moving forward, the Spanish and Portuguese programs have plans for collaboration and expansion of the StoryMaps tool into the study abroad course.

Continuing to Evolve

Based on our positive experience with using StoryMaps, we are considering ways to expand its use. The ArcGIS StoryMaps platform also provides us with an ability to link students participating in overseas immersions with stateside foreign language learners in real-time. Those studying abroad can utilize the platform as part of a course assignment or to blog about their daily adventures, while students learning the same target language, at perhaps lower proficiency levels, could then select from a variety of different postings to StoryMaps to discuss in the classroom. Students could also request additional regional information, propose cultural outings, or ask language-related questions to those overseas. Students abroad could then follow up on the questions and requests through subsequent posts. These types of collaborative interactions may help to motivate students to continue learning a foreign language in order to participate in future immersion programs. Furthermore, assignments would be kept fresh, fun, and relevant.

Inter-departmental collaboration through ArcGIS is another benefit of the program. The partnership between the DFL and the GEnE proved fruitful for both organizations through the sharing of resources, map making products, and technological know-how. We now aim to expand our collaboration with GEnE and other academic departments through sharing language students’ immersion experience StoryMaps. We hope that these efforts lead to future collaborative projects with students and faculty from around the United States Military Academy.

Lastly, ArcGIS StoryMaps is beneficial for recruiting prospective students into foreign language programs. The current technology mimics popular computer applications and websites that students are likely already familiar with (Godwin-Jones, 2016). Upon receiving permission from former students, language departments could easily maintain a database of past immersion experiences within the site. The next step would include touchscreen displays in academic buildings and popular places around campus. Students could scroll through the different StoryMaps at their leisure where they would see classmates, friends, or even themselves, traveling and interacting with people of different languages and cultures. In addition, such a format likely resonates much better with students than traditional bulletin boards which are not interactive and time-consuming to update.

Conclusion

Our approach to maximizing opportunities for student engagement and reflection while abroad continues to evolve. While the Spanish program will continue to utilize the digital scrapbook approach to documenting reflection during study abroad, it will also expand to incorporate ArcGIS StoryMaps as a reflection tool during language immersion based on the success experienced by the Portuguese program. The continual growth and development of Esri’s software and the addition of new ArcGIS StoryMaps tools will further enhance our digital map making and journaling efforts for short and long-term immersion experiences. ArcGIS StoryMaps allows our students to create individual map-based journals as they traverse the globe. We will also lean on StoryMaps to motivate current students to achieve higher language proficiencies and cultural competencies and recruit new students to pursue a path of foreign language learning. If this sounds like an exciting addition to your foreign language program, we hope you consider these ways to incorporate journaling through digital books and through map making into your own study abroad curriculum.

References

Dessein, E., & Urlaub, P. (2020). Digital mapmaking and developing a sense of place in study abroad contexts. The French Review, 93(4), 159-170.

Gabaudan, O. (2016). Too soon to fly the coop? Online journaling to support students’ learning during their Erasmus study visit. ReCALL, 28(2), 123-146.

Godwin-Jones, R. (2016). Integrating technology into study abroad. Language Learning & Technology, 20(1), 1-20.

Schenker, T. (2021). Online journaling and language learning in intensive summer study abroad programs. Language Teaching Research, 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1177/1361688211036673

Stewart, J. A. (2010). Using e‐journals to assess students’ language awareness and social identity during study abroad. Foreign Language Annals, 43(1), 138-159.

Urlaub, P., & Dessein, E. (2023). Sense of place, imaginative mobility, and intercultural awareness through a map making project in a study abroad program. Frontiers: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Study Abroad, 35(1), 305-324.