Introducing The Reactor Room: An Immersive Chernobyl Exhibition

By José Vergara, Visiting Assistant Professor of Russian, Swarthmore College

Introduction

When my students and I first began studying Chernobyl in late January, we had little idea that the entire globe would soon be swept up by a similar “invisible enemy,” as the nuclear disaster’s radioactive fallout is frequently called. We had plunged into the discomforting world of Chernobyl—its history, its effects, its representations across a range of media and traditions—and we found ourselves reeling from the shock of sudden unexpected parallels. We took some time in February to debate the media’s representation of the early response to COVID-19 as “Trump’s Chernobyl” and “China’s Chernobyl,” but by mid-spring break, we were faced with an entirely different reality, and many of the logistics of the class, “Chernobyl: Nuclear Narratives and the Environment,” of course, had to be adjusted.

In designing my new course, I wanted to experiment with the three main writing assignments. First there would be a more or less traditional essay. For the final task, students chose between a grant proposal and a creative response (short story or play). Sandwiched in between, however, would come a project culminating in a physical installation: a mock nuclear plant control room to be housed in Swarthmore’s McCabe Library. The students’ individual digital/writing projects would then be displayed on iPads built into an interactive control panel. Inspired by the “total installations” of the Russian Conceptualist artists Ilya and Emilia Kabakov, I envisioned it as a public-facing research project that would be expressly aimed toward an audience beyond the confines of our classroom. Visitors would engage with a variety of materials while immersed in this space devoted to the lasting memory of Chernobyl.

So much for the original plan.

What we—and I mostly mean my industrious students and collaborators at Swarthmore’s Libraries and Language Center—managed to pull off was just as impressive considering the circumstances. Scattered across the country and with one intrepid student still Zooming into our synchronous class sessions from another continent, we turned our focus to the digital component of the exhibition. Even if we could not build The Reactor Room itself, we could offer a virtual version that anyone can now access.

Concept and Guidelines

From the beginning, I considered the installation an opportunity for students to individualize their learning by investigating a research topic of their choosing. This idea would not change as we pivoted to a digital format; I did not impose any formal guidelines beyond the following:

- Use one text from the syllabus (novel, story, video game, play, article, etc.).

- Use at least one text from the course bibliography that we are not reading together as a class.

- Written and digital components. The format of your contribution may vary (StoryMap, a study of sound design in films/video games/VR related to Chernobyl, a comparison of Chernobyl radiation maps and narratives using ArcGIS, etc.). However, you must produce an accompanying document that contains an argument/interpretation of some sort, analysis, evidence, and a conclusion. In some cases, this writing will be incorporated directly into the digital portion of your project, while in others it will be featured alongside the interactive component. Again, this depends on your interests and your chosen platform. Possible tools include StoryMap JS, Storyline JS, Timeline JS, Soundcite JS, ArcGIS StoryMaps, RAW Graphs, and Hypothesis.

The result was a collection of projects with just as wide a range of content as the course: radiation’s effects on mushrooms and the Red Forest, Chernobyl in video games, casualty counts, the American doctor Robert Peter Gale, children, babushkas, and much more.

The implementation process changed once the pandemic struck, of course, but in general terms, the plan remained the same. In the first week of class, I gave the students an overview of the project and suggested that they keep in mind potential topics as we moved through the material.

Then, as a first step students submitted a short proposal via a Google Form including their selected texts, digital tool/platform, and a brief abstract of what they intended to accomplish with their research. The original plan to share the project with the College community before summer break meant that in some cases students would need to read ahead or at least consider what other topics we had not yet fully covered might be of interest to them.

To support the students in brainstorming, my collaborators in the Swarthmore Language Resource Center and the College Libraries and I offered multiple open lab hours for students to drop in to ask questions; the first was held on campus before spring break, the final two on Zoom. They really seemed to appreciate the opportunity to bounce ideas off us and to see how some of the possible tools actually work and what kinds of curatorial products they can generate.

Students then submitted what I called a “polished” draft of their project materials to me, their peer reviewer, and their Writing Center Associate in late April. This draft included both the digital content (as a link) and writing components (as a document that each reader could mark up). Each student was responsible for reading and commenting on the work of one other student in the class using a peer review feedback form that asked four targeted questions:

- In just one or two sentences, state what position you think the writer is taking. Place stars around the sentence that you think presents the thesis (the main argument).

- List some of the evidence used to support the writer’s argument. Which pieces of evidence do you think are the strongest? Which are the weakest? Why?

- After reading the materials, do you agree or disagree with the writer’s position? Why or why not?

- Does the writer’s language appear to be geared toward a broad, public audience? How so? How not?

Using all this feedback, students would revise and submit a final version of their project materials by May 7. In most cases, I made a few additional corrections and suggestions that students implemented before we officially launched the site in mid-May. A virtual launch was held on Zoom on May 20 so that we could honor their work and share it with invited guests from the college community.

As the projects came together, Digital Scholarship Librarian Nabil Kashyap and I asked students to complete two forms that would allow us to build a shared site on which to gather all their work. One form collected information about them and their project: name to be displayed (optional), short biography (optional), project title, description, image, and associated URLs and files. The second form addressed permissions, including sharing their projects on the site and archiving their work in a College database. (Only two out of nearly three dozen students opted to withhold their projects from the public.)

Challenges

One of the biggest challenges of such an open-ended approach was determining how to best support students who were working with an assortment of tools and coming at the project with varied backgrounds in digital scholarship and research in general, especially when we could only communicate via email and Zoom. The writing-intensive course itself was open to all and presupposed no background knowledge. Probably the most common suggestion we gave was to consider how to make sure a topic worked together with the selected digital platform and vice versa. It was a matter of ensuring the content and form of the project were in conversation with each other, so to speak, rather than working at odds. So, for someone interested in Chernobyl-inspired music, it made sense to direct them to Soundcite JS as a tool that powerfully uses samples to emphasize a certain point in an essay.

Other ideas brought to mind less obvious matches, so students had to spend more time conceptualizing the story they hoped to tell. One of the course’s key concepts was the manifold narratives of Chernobyl and how they shape public understanding of this event, which bears numerous ongoing effects often too diffuse to fully comprehend. As we read and watched and played many versions, fictional and not, of the tragedy, we interrogated each one to see what fresh insights it might provide into Chernobyl, as a whole or with regard to a particular aspect. We considered why these stories are told, deformed, and fictionalized. We asked who gets to tell them and why they do so (or not). This project, then, prompted students to sharpen their understanding of some details of Chernobyl and to figure out how to conscientiously share that knowledge with an audience who may not know anything about the disaster beyond what we’ve all heard: an explosion, radiation, fear, mutants. It thus required them to blend their curiosity with imagination as they put themselves in the shoes of the lay reader even after they had immersed themselves in all things Chernobyl for several months.

There were logistical issues, too. After we scattered from Swarthmore during spring break, students lost direct access to many library resources. To make things easier, my TA and I compiled as many materials as we could on the course Moodle page; these included readily accessible articles and e-books found through databases, but students also availed themselves of our library’s incredible continuing support.

When it came to image and video copyright issues, I learned quickly that I had to extensively train most students. After I fielded several individual emails and Zoom meetings, I decided to put together a “Guide to Copyright and Finding Free-to-Use Images” that I could share with the entire class in order to address common questions. This document introduced students to standard terms (all rights reserved, transformation, excerpts, and so on) and directed students to numerous databases where they could potentially find free-to-use images relevant to their work: Google Images, Wikimedia Commons, Flickr, Pixabay, and Pexels. Having a clear how-to guide with step-by-step instructions and screenshots clarified many of the issues we experienced with students initially using copyrighted materials.

Sample Projects

Despite these obvious and at times significant barriers to essential research practices, the class generated many rich, well-informed projects that run the gamut in terms of approach and content. Here are a few.

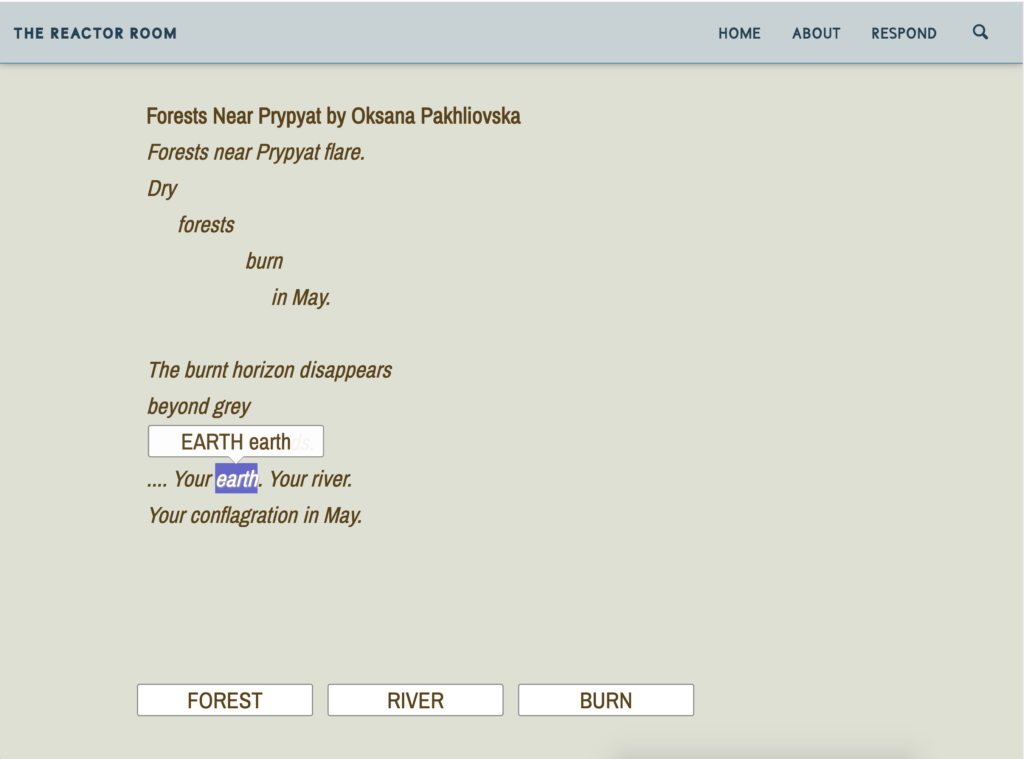

Early in the semester, after covering some of the basic timeline and history of Chernobyl, we read several poems by Ukrainian authors on the disaster and its effects on the people and nature in the region. Students were particularly fascinated by the metaphors these poets used, as well as the connections between the various texts. When it came to the installation, two of them tackled these topics through very different approaches. Lucas used the choose-your-own-adventure style story builder Texture to lead the audience into a labyrinth of linkages in “Poetry of Chernobyl.” Readers follow a predetermined path until the game opens up, and from there, they must drag and drop word tiles to access further poems. Certain words, of course, take the reader back to a previously seen work, creating what Lucas in his accompanying essay calls “the wave-like oscillation of words, at once connecting poetry and Chernobyl by addressing the same concept […] and pushing the two apart by showing a variety of different nuances to that meaning.”

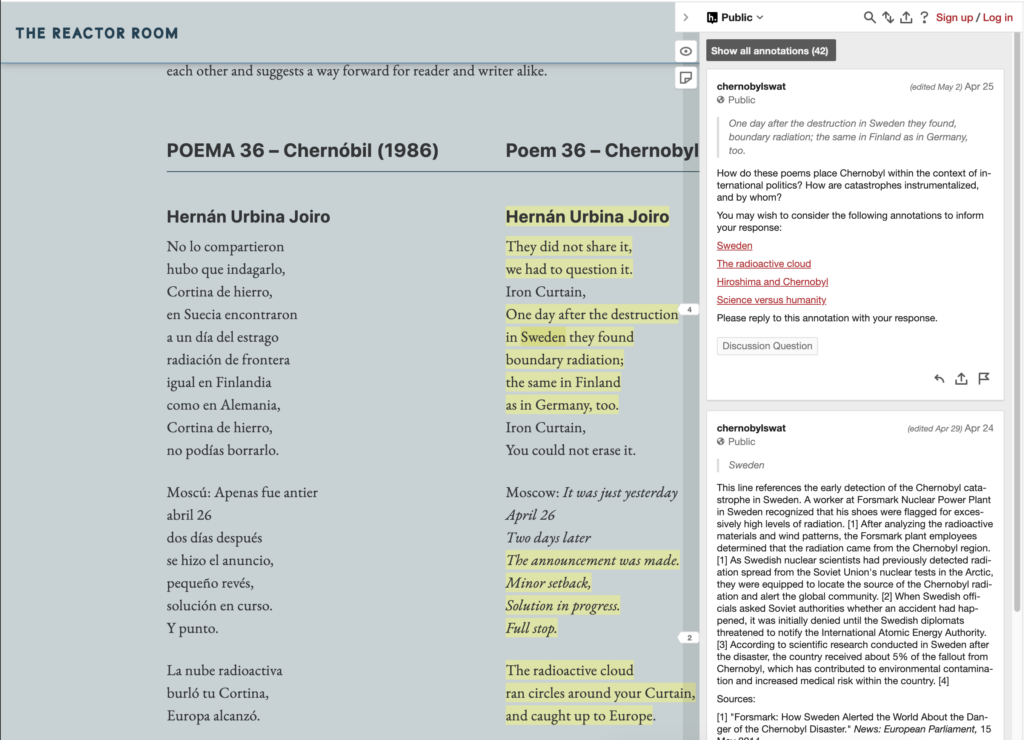

Combining her majors and language skills, Grace opted to translate and compare Chernobyl-inspired poetry from three countries: Colombia, Soviet Russia, and Ukraine. She used the annotation tool Hypothesis to conduct close readings of three poems in “The Chernobyl Kaleidoscope.” In addition to providing biographical and contextual information, Grace notes links between the works and suggests that they each represent a kind of breakdown of language that resulted from the Chernobyl experience.

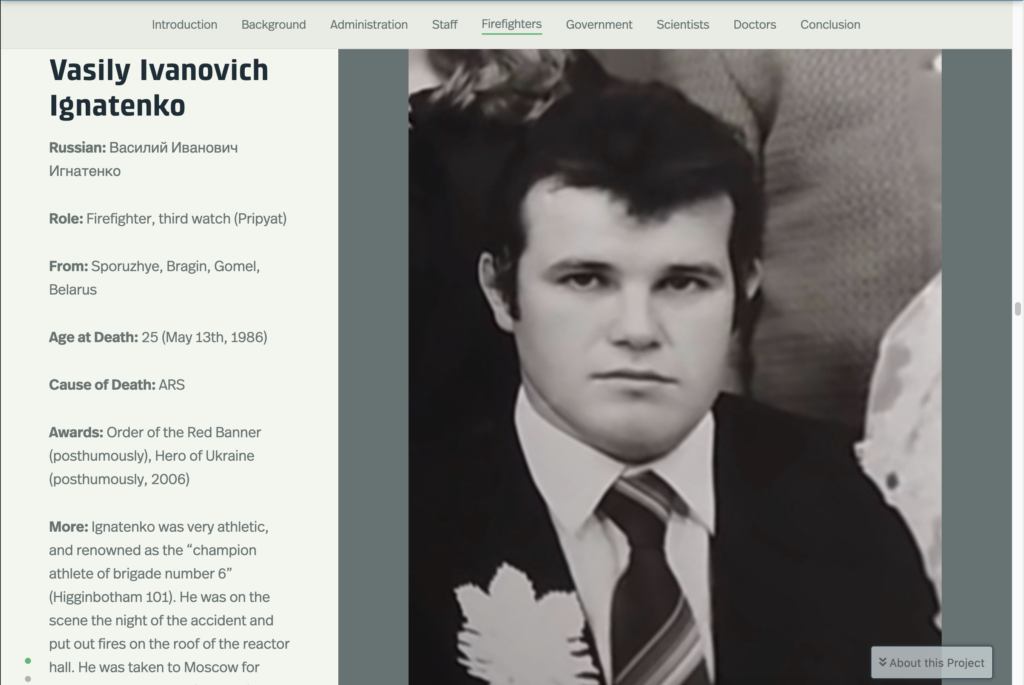

A particularly helpful project for anyone new to Chernobyl, Alexa’s “Parts of a Whole: Key Figures in the Chernobyl Nuclear Catastrophe” introduces readers to key players in six different categories: the Chernobyl plant’s administration and staff, firefighters, government officials, scientists, and doctors. Throughout the semester we discussed the importance of considering the balance between telling the story of Chernobyl with a focus on those in power, on the one hand, and everyday people who suffered as a result of the accident, on the other. This ArcGIS StoryMap blends text, image, and video quite effectively to show the various levers of power that led and responded to the nuclear disaster, as well as how others tried to help in the aftermath.

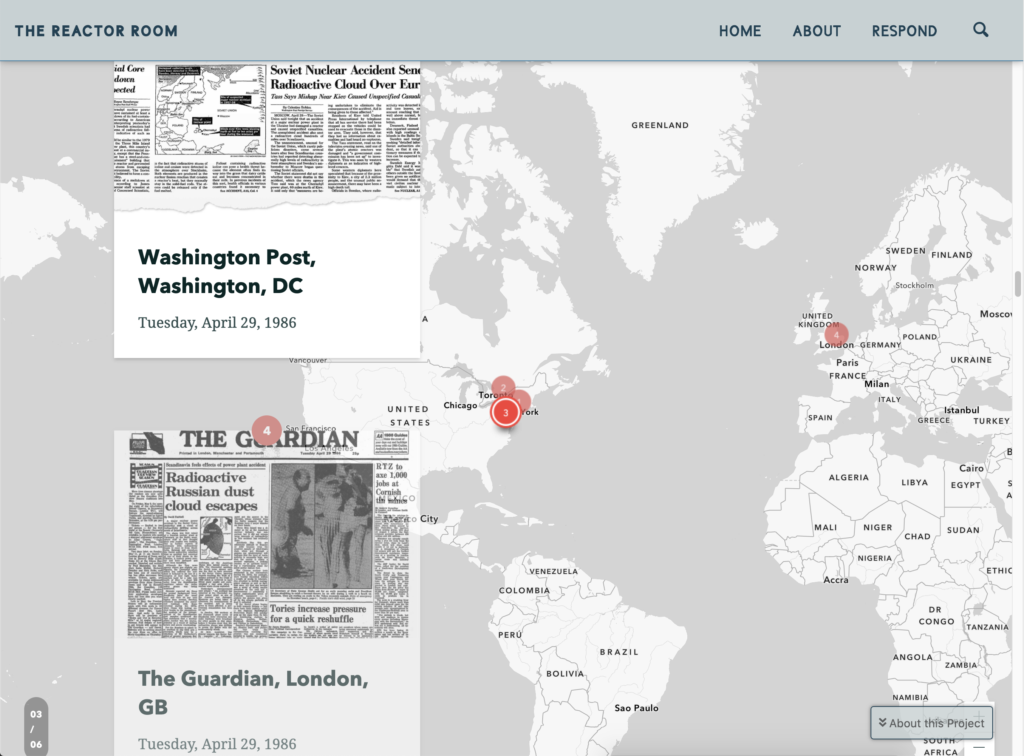

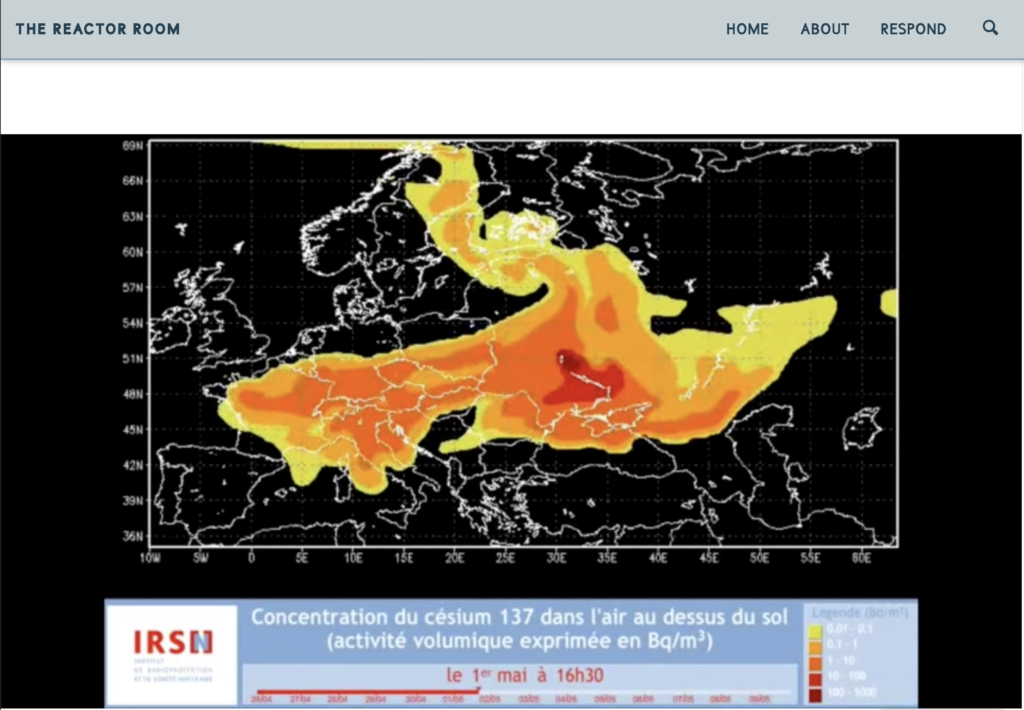

Also using ArcGIS, Nicole designed “Chernobyl: Global News Coverage” to highlight the disparities in access to information about the nuclear disaster around the world. Her project puts newspaper front pages from the US, England, Russia, Ukraine, and Australia into direct conversation with one another, demonstrating how Soviet sources remained silent while foreign nations sought to warn their citizens about the dangers of radiation. A visualization of radionuclide distribution contrasts strikingly with these headlines — two kinds of spread, one that could not be controlled with borders.

Elliot focused on time, rather than space, in his project, “The Accident: A Timeline of the Chernobyl Reactor Explosion.” Timeline JS permitted him to delineate the crucial moments that led to the explosion. Additionally, he created short GIFs and placed them over a static background to illustrate the reactor’s power output at these various stages and to simulate the experience of seeing the numbers drop precipitously and rocket to uncontrollable levels depending on what the plant operators were doing. Elliot’s visualizations are simple, but there is something unnerving about watching these changes on the screen.

A more creative approach, Sky’s “Chernobyl Symphony” uses samples from previously composed pieces of music and sounds associated with the disaster (Geiger counters, voices of officials) to trace the “plot” of Chernobyl, from the calm, sunny day that preceded the explosion, to the cover-up and panic that ensued. This piece, which is hosted on Soundcloud, is accompanied by an essay in which Sky considers what it means to represent Chernobyl through sound rather than word. The essay and music together speak to the emotional and existential questions that we wrestled with throughout the semester all along, so the installation gave Sky an opportunity to put into practice what we had been studying. The original plan was to have Sky’s project soundtrack the physical installation room. For now, like so much else in the world, the “Chernobyl Symphony” has been silenced in its intended form.

Conclusion

Throughout this assignment, scaffolded from early March through mid-May, and both despite and thanks to the challenge of going totally virtual, students explored the possibilities of digital curation. In essence, I asked my students to think about how we might present the course material to a public audience in a manner that is both widely accessible and academically rigorous. I likewise wanted to extend the lifespan of their work; I felt that this research should not disappear once the semester ended, but rather live on and find a broader audience than just me and their peer reviewers. After the very positive reception HBO’s Chernobyl received, it seemed to me that this was an excellent time for students to use their newfound knowledge to further understanding of this cultural phenomenon. (As I’ve been telling everyone, though, I promise I came up with the idea for the course long before the miniseries was even announced!)

The digital humanities, as embodied in this mammoth of a project, presented exciting tools for doing so. Whether it was through an analysis or covers of songs inspired by Chernobyl, an exploration of conspiracy theories that the disaster generated, or a study of street art found in Pripyat, this interactive exhibition aimed to help unpack some of Chernobyl’s mythology and to inspire students to consider new modes of responsible storytelling.