Pronunciation Technology: Global Community and Innovative Tools in Forvo and NetProF Pronunciation Feedback

Joan Palmiter Bajorek, Doctoral Student at the University of Arizona, Second Language Acquisition and Teaching (SLAT) Program.

Joan Palmiter Bajorek, Doctoral Student at the University of Arizona, Second Language Acquisition and Teaching (SLAT) Program.

DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.69732/LLVU8732

“I want to be fluent.”

“I want to practice speaking.”

“How do you say that?”

“My pronunciation is terrible.”

My students have uttered these phrases –sentiments echoed in language learning classrooms worldwide. Learners want to be able to communicate effectively and often rank speaking and pronunciation and the ability to have a conversation as the most desirable language skills to acquire (Vivrette, 2010). However, even in the most communicative of classrooms, there is often an element missing – explicit instruction on intelligible second language (L2) pronunciation (Trofimovich & Isaacs, 2016). Research indicates that many L2 learners are not getting enough pronunciation support in the typical language classroom (Lord & Fionda, 2013). Speech technology provides novel pronunciation development opportunities for language learners.

In this article, I present and compare the free pronunciation resources Forvo and NetProF which are contemporary tools for language learners, instructors, and researchers. I examine the pros and cons for each technology and I summarize the affordances of these tools in comparison table.

What is Forvo?

Forvo (www.forvo.com), an online pronunciation dictionary, hosts over 2.2 million sound files that represent utterances of native speakers of 349 languages (“Forvo,” 2008). Supported on the desktop as well as apps on iPhones ($2.99) and Androids ($2.99), Forvo hosts languages that include not only Russian, English, and Spanish, but also less common languages such as Irish, Indonesian, Tagalog, and Lakota. Functionally, the website is a dictionary that includes one and sometimes multiple sound files for each word pronounced by native speakers from around the world. Members of the site add sound files, add words they want to be pronounced, vote on sound files, make favorites lists, and download mp3 files from the website. Entries of sound files come in single words as well as phrases and full sentences.

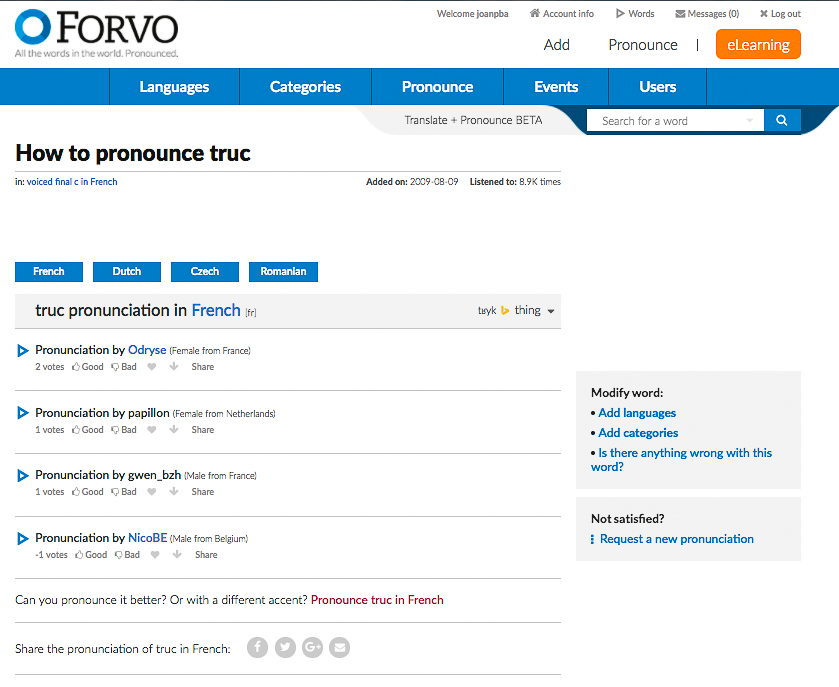

Let’s consider an example entry in Forvo from French speakers, see Picture 1. “Truc” /tʁyk/ is the colloquial and commonly used noun meaning “thing.” There are 4 sound files of the word in isolation from native speakers from France, the Netherlands, and Belgium. While some of the specific audio recordings have positive “up votes,” one has a “down vote.” While the site overall promotes diversity and variation of spoken language, there does seem to be a preference in this voting system for “standard” accents by users. Only members of the site can vote on sound files and they can only vote on sound files in their native language, not just any passerby on the website. As learners, instructors, and researchers, it’s wonderful to have a range of speakers pronouncing the same words. It’s a strength of the site that supplements most pedagogical material that does not always discuss variation. I say, take these ratings with a grain of salt and listen to all of the versions to compare and contrast how people sound around the world.

Join the Community: Add Your Own Sound Files

The site actively prompts users to add sound files of different accents with messages on sidebars that read, “Can you pronounce it better? Or with a different accent?” and also prompts the user to make modifications to the entry. The site is ever evolving and growing based on member submissions and curated by the greater language community. While Forvo might not be well-known by the academic language community, it is certainly well-loved and used by its users. For example, these specific sound files for “truc” have been accessed 8.9K times. As comparison points of words of varying frequency, “je”/ “I” has been listened to over 2.5 million times, “phacochère”/ “warthog” at 1.5K times, and “inflammabilité”/ “flammability” at 366 times. Even for lower frequency words such as “warthog,” that is a lot of listeners worldwide listening to these sound files.

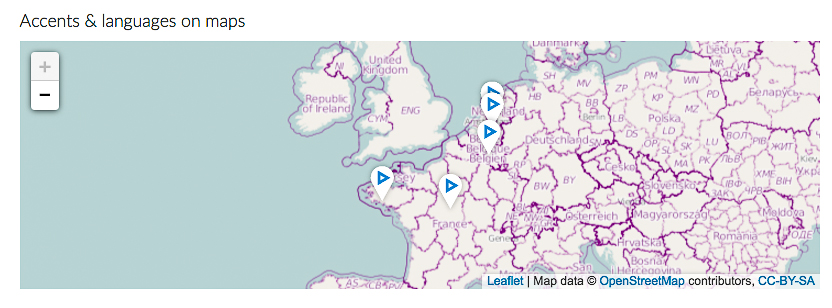

Across the Forvo website, not all entries are as complete as others. While some entries have several sound files, locations (see Picture 2), and genders of speakers, others have only a few samples of the word or phrase. This is the nature of online communities with membership and usage for free. Despite this great variation across entries, the data on Forvo can help us understand natural and authentic variation across speakers of the same language.

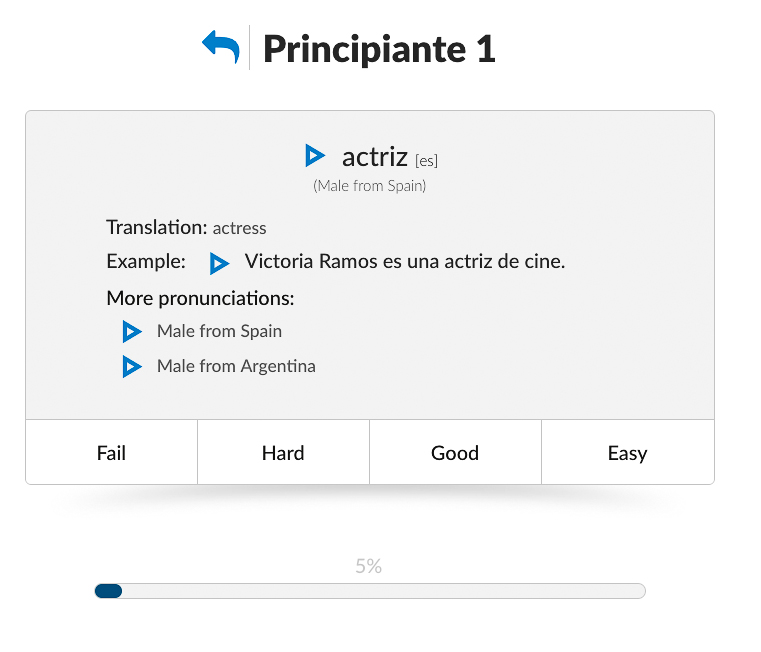

In addition to the dictionary content, the website has recently added an interactive flashcard option where learners can see a word and “flip” the card to hear the most popular sound file of the word as well as rate how “difficult” the vocabulary word pronunciation was for them though this could be explained far more clearly on the website (Picture 3).

Forvo Overview: Pros and Cons

Pros:

- Real: Authentic, native speaker speech

- Detailed: Dialectal variation noted, sometimes mapped geographically

- Large Size: Huge, interactive learning community

- Evolving Site: Ever-growing number of sound files

- Good Coverage: Each word/phrasal has roughly 5-10 sound files

- Interactive Aspects: Ability to “quiz” yourself on pronunciation

Cons:

- Dictionary: If we consider Forvo to truly be a dictionary, it could have better support for translations, International Phonetic Alphabet transcriptions, and other translation functions.

- Incomplete: Not all sound files have International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) support

- Context: Not all words have explanations as to meaning and context usage

- Word Entries: It is not completely clear which words and phrases are on the site. Forvo may not have the exact thing you are looking for, but you can make requests.

Best Ways to Use Forvo: For Learners, Instructors, and Researchers

- Learners, Instructors, and Researchers: Forvo can show a great variety of pronunciations found across the world that you might not always get exposed to in class. For example, it’s great to hear francophone speakers from Belgium, Switzerland, and Canada in addition to those from France. This is similar for Spanish and English, languages that vary significantly by region and country. See the English word “joker” pronounced by British, Canadian, American, and Irish speakers.

- Learner: Another great way to consider how Forvo can support your language learning is consider it as a complement to multilingual online dictionary websites such as WordReference, (wordreference.com) (Kellogg, 1999) and Linguee (http://www.linguee.com) (Frahling, 2017).

- Instructors: Design lessons that require learners to make a “learner corpus” that might target specific phonemes, specific words, or words and phrases of varying frequencies.

- Researchers: Can be used as a native speaker corpus. Only members can submit sound files and they are verified before submissions can be recorded. Downloaded utterances of native speakers could be used in the analysis of an isolated phoneme or coarticulation study. Although mostly male speakers and few sound files, there is still a wealth of data on the site.

What is “NetProF Pronunciation Feedback”?

NetProF is a free pronunciation tool created through a collaboration of the Defense of Language Institute (DLI) and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Lincoln Laboratory (Institute & Laboratory, 2017). Supported by the Defense Language Institute Foreign Language Center, which is a government organization in Monterey, California, this software supports 20 languages. Many of these languages are less-commonly taught languages in the US, see the Comparison Table, such as 3 types of Pashto, Urdu, and Chinese. While the military may use the software for other purposes, the free version for civilians has phenomenal segmentation capacities for learner pronunciation that are far superior to most commercial software, i.e. Rosetta Stone, Duolingo, Babbel, Mango Languages, etc. Almost unparalleled for language consumers, NetProF segments speech and gives users specific and immediate information about their utterances (1). Unfortunately, the user interface is clunky and can be overwhelming given the vast number of features provided. There is little explanation of features, but these caveats are easily overlooked when users are given access to the ability to analyze and learn more about their speech through empirical measures. There are four main components of the site.Working with a word or phrase, users can “practice” and get feedback, record their own words to word lists, get an analysis report on all the segments they have spoken, and quiz themselves in a flashcard module. Let’s look at some examples.

Practice: “Learn Pronunciation”

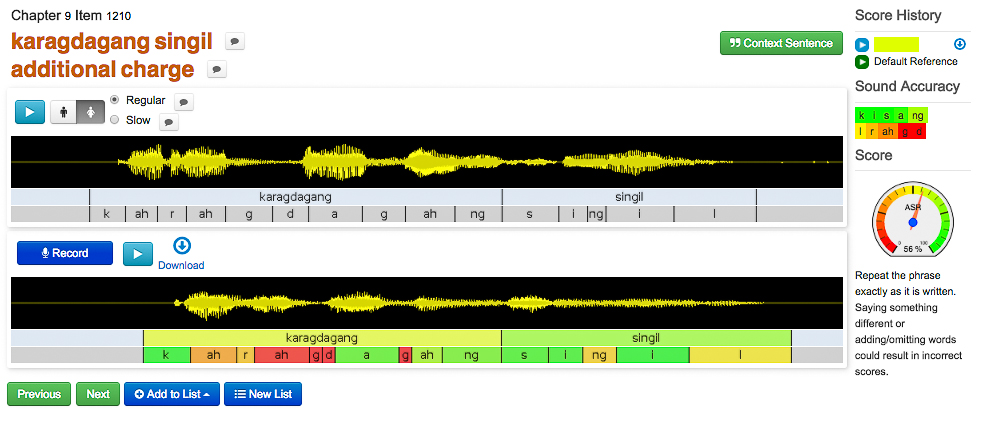

In the practice section of the software, learners are provided the opportunity to pronounce vocabulary words several times with detailed feedback, see Picture 4. In this example, the learner sees the target Tagalog utterance as well as the English translation. There is an audio file with each vocabulary word, some have only a male speaker, while other files have a female speaker or a slowed down version of either sex. Underneath, the waveform of the utterance is shown and underneath is the utterance segmented by phoneme-like segmentations, orthographic symbols that may be more accessible for non-linguists than the standard International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA). For the future, these will be referred to as “segments.” When the learner clicks and holds the “record” button, the automatic speech recognition software records, saves, and analyzes the utterance. Then the production will be coded by segment and given a score out of 100% for each segment as well as the utterance as a whole. There is no indication to what this percentage score means. The software keeps a “score history” of all of the production made by the individual learner. These can be played back for the learner and the segments will be saved for which ones the learner is consistently producing well, and those that need improvement.

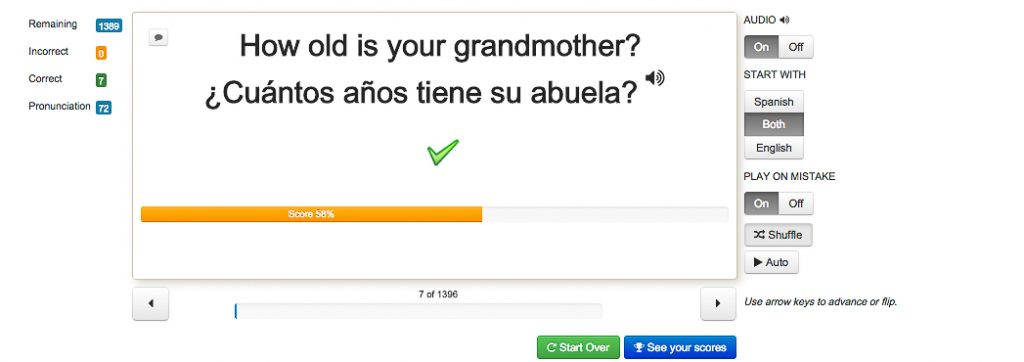

Record, Flashcard Quiz

If the practice module feels like self-study, the record section feels like flashcard quiz. The learner is presented with a word from the unit or chapters of vocabulary words, see Picture 5. This section is customizable as seen from the options on the right hand side. The learner can choose to hear the audio before pronouncing the word/phrase. They can see the Spanish and English, both or only in one language (this gives an opportunity for translation practice, in addition). After recording a word/phrase, the learner then is given an overall score of the utterance where they do not get to see the segmented unit breakdown of the oral production. The audio can also be played again if the score given to the overall utterance is too low, though the threshold for this cutoff is not stated in the software. Again, all of these productions are saved in the software for the analysis component.

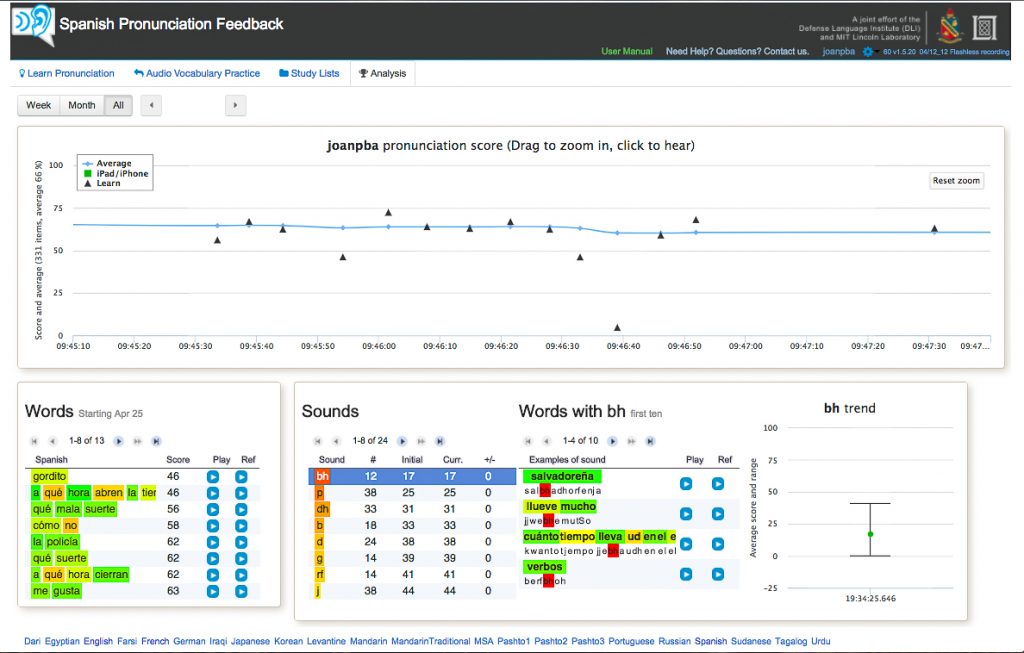

Analysis: Analyzing Your Speech by Segment

One of the most phenomenal aspects of this software is how thoughtful it is about segmentation, see Pictures 4 and 6. Each word is segmented by “phonemes,” but words also get overall scores. Then the learner’s utterances are saved for the “analysis” component of the website which keeps an entire database of the learner’s productions by word and by segment. In the analysis section, the learner can zoom in on the saved recordings they have made in the “practice” and “record” sections. On the top section, the timeline of audio recordings made by the learner appear on a graph, time versus score. Below are the utterances produced, segmented by word, then segmented by sound, and then grouped by segment scores.

It’s unclear how users would understand what these analyses mean outside of the software. Overall, knowing that you struggle with “bh” most likely would not help the typical learner when they travel to Mexico City and want to talk with locals.

Create: “Study Lists” For Instructors

While the software comes already with several chapters worth of content, instructors can create their own word lists that are segmented by the automatic speech recognition (ASR) software. Study lists can be saved and marked as public or private. When individuals make free accounts to use the software, they do so as a “learner” or “instructor,” which leads to different types of interactions with the software. However, instructors and learners can use the vast vocabulary words and phrases already provided within the software. But be forewarned that some of the material may not be applicable to all learners, i.e. revolutionary army, interpreter, captain, vehicle plate, etc. (all of these are words built into the software for the Tagalog language).

Critique of NetProF

What do the scores mean? Are they valid and reliable?

Validity: I am a native speaker of American English- I’m originally from the Pacific Northwest of the United States. To varying degrees, I speak French (C1-C2: worked in France and have studied the language for several years), Spanish (B1-B2: my instructors have all been Spaniards), and Italian (A2: lived in Rome for a few months).

My average NetProF scores for English are around 54%, French at 57%, Spanish at 66%. Italian is not a supported language in this software. How is it possible that my native speaker production of “I” is getting me scores between 28% and 62%? This makes me question the validity of the software when it talks about segmentation and accuracy. The reliability of the scores is also questionable. When a fan is turned on or the speaker is closer or farther away from the computer, the scores change dramatically. Thus, while the software is certainly sophisticated in some respects of how it maps phonemes, it is far from perfect when it comes to the implications of what the scores mean.

Issues of Gender Mismatches: If a male speaker makes the target speaker utterance and the user of the software is a woman, the speech recognition software may have trouble matching up the utterances, depending on how the software rates the scores, for about phonetics and speech recognition software see (Holmes & Holmes, 2001; Ladefoged & Johnson, 2011). Male speakers created most of the audio for the Spanish and French vocabulary words. Women created most of the English language audio files. However, this again proves problematic for the reliability of the software if my scores as a female, native English speaker are compared to a female English speaker and still getting extremely low scores for pronunciation production.

Still Extremely Innovative

Despite the above caveats to why this software still has room for improvement, the way this software is conceptualized is vastly different from much of contemporary pronunciation technology. The idea that learners could get specific, automatic feedback on their production for smaller units, but also a larger analysis of their second language speech, is astounding and exciting. Hopefully the future will continue to provide language students with such learner-centered tools to support their pronunciation development.

NetProF Overview: Pros and Cons

Pros:

- Feedback: Fine-grained pronunciation feedback unlike almost any others available

- Existing Material: Built in vocabulary words and section, large number of audio files

- Feedback: Immediate and specific analyses of speech

- Customizable: Creates personalized database of user speech production

- Interactivity: Ability to “quiz” yourself on your pronunciation

- Range of Languages: Support for many underserved languages

Cons:

- Questionable Scores: Low validity and reliability

- Men Dominate: Mostly male speakers, problematic for female speakers to match their voices

- Choice of Vocab: Vocabulary pertaining to military protocol might not be pertinent to all learners

- User Interface: Strange and Difficult to Interpret User-Interface

- Dialect Neglect: ex: the software does not say which dialect of Spanish is being taught

- Difficult to Interpret: Barriers to understand what is going on for the typical, non-linguist learner

- Instructions: No explicit instruction about how to make improvements

- Phoneme Coding: Phoneme-like symbols might be hard to understand

Best Ways to Use Forvo: For Learners, Instructors, and Researchers

- Learner: The software might be difficult to interpret for learners and would be best used with support from instructors. For example, learners could be asked by an instructor to focus on a specific word list. Learners could interact with the software, but might not get much out of the software without more explanations.

- Instructors: Design lessons that require learners to speak specific target phonemes, specific words, or words and phrases of varying frequencies.

- Researchers: This software can be used to consider phonemes that are difficult for acquisition. It also could be used to consider ideas of frequency and functional load of minimal pairs (Brown, 1988; Munro & Derwing, 2006). However, there are large limitations to the type of research that can be conducted due to the questionable reliability and validity of the software.

| Category | Forvo | NetProF Pronunciation Feedback |

| Cost | Free Online, $2.99 Apps. | Free. |

| Platforms | Desktop Web browser, iPhone, Android. | Desktop Web browser, iPad, iPhone. |

| Languages Supported | 349 Languages: See full list here.

|

20 Languages: Chinese (Simplified), Chinese (Traditional), Dari, Egyptian, English, Farsi, French, German, Iraqi, Japanese, Modern Standard Arabic, Pashto 1, Pashto 2, Pashto 3, Portuguese, Russian, Spanish, Sudanese, Tagalog, Urdu. |

| Main Service Provided | Native Speaker Audio Files. | Pronunciation feedback and analysis of speech production. |

| For Learners | Investigate target words and sounds. Learner corpus. |

Can get specific feedback about their pronunciation. |

| For Instructors | Point Learners to native speech production. Look at target words, phrases, phoneme. |

Can create word lists for students. |

| For Researchers | Corpus of native speech audio files. | Research the efficacy of targeted feedback on second language pronunciation. |

Conclusions and Further Directions

For many of us in the language education and pronunciation research communities, Forvo and NetProF are significant improvements from what we have been able to offer to our language students previously. Learners can be exposed to all types of native speaker production for a plethora of words, something textbooks and individual teachers alone cannot provide. Learners can get feedback on their production and be supported in new ways of framing their pronunciation and overall speech production. Instructors can empower their students to use these novel tools in ways that fit with learner needs and curriculum constraints. Both of these tools could accompany pronunciation- or phonetic-specific courses but also be used effectively in standard language learning classes. Researchers can certainly use these resources as ways to consider phonemes and pronunciation corpora, but the many caveats described in this article may prove to be too great of methodological barriers for some.

In the future, it would be fantastic to see the Forvo site evolve and expand. There is great potential for contributors to support aspects of translation, contextual material, and IPA to foster holistic understandings of the words being spoken. NetProF would do well to explain its features better to its users. The condensed way the material is presented is a barrier for usage and the ability to appreciate the full functionality of the software. With these tools, we can better support pronunciation development in our language students and enhance their understandings of language and global community along the way.

__________________________

(1) But see “Elsa” software for a different perspective on other commercial software of this nature https://www.elsaspeak.com/home.

References

Brown, A. (1988). Functional Load and the Teaching of Pronunciation. Tesol Quarterly, 22(4), 593-606. doi:10.2307/3587258

Forvo. (2008). Retrieved from https://forvo.com/

Frahling, G. (2017). Linguee. Retrieved from http://www.linguee.com/

Holmes, J. N., & Holmes, W. (2001). Speech synthesis and recognition (2nd ed.). New York, London: Taylor & Francis.

Institute, D. o. L., & Laboratory, M. L. (Producer). (2017). NetProF Pronunciation Feedback. Retrieved from https://np.ll.mit.edu/

Kellogg, M. (1999). WordReference.com. Retrieved from http://www.wordreference.com/

Ladefoged, P., & Johnson, K. (2011). A course in phonetics. Boston, MA: Wadsworth/Cengage Learning.

Lord, G., & Fionda, M. I. (2013). Teaching Pronunciation in Second Language Spanish The Handbook of Spanish Second Language Acquisition (pp. 514-529): John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Munro, M. J., & Derwing, T. M. (2006). The functional load principle in ESL pronunciation instruction: An exploratory study. System, 34(4), 520-531. doi:10.1016/j.system.2006.09.004

Trofimovich, P., & Isaacs, T. (2016). Second Language Pronunciation Assessment: A Look at the Present and the Future. Second Language Pronunciation Assessment, 259.

Vivrette, J. (2010). Cultivating awareness: Register and context in first-year Arabic. Retrieved from http://blc.berkeley.edu/2010/09/15/cultivating_awareness_register_and_context_in_first-year_arabic/

Dear Joan Palmiter Bajorek,

I am learning English and I am so naiive to pronunciation. I do not have access to face2face but I like video lessons. Which one is out of shelf I can use for Amr Eng.

Thank you.