Engaging Students Online through an OER Poetry Project

By Svitlana Malykhina and Nadiya Prokopyeva, Boston University

Introduction

BU Russian Poetry is a comprehensive multimedia Open Educational Resource (OER) where students read poetry and experiment in a laboratory for new forms of analysis while developing their language skills. The BU Digital Russian Poetry Project has grown out of the Russian program’s mission to inspire learners of Russian, many of whom have written poems themselves, to read poetry in the original to capture a poem’s mood, and the music of words. We place a high emphasis on the cultural and communicative competence of our students, as well as an ability for critical thinking and intercultural communication. We introduce learners of Russian to the treasures of Russian poetry in the original, both canonical and non-canonical texts, starting with the poets of the Silver Age in the twentieth century and moving chronologically into the twenty-first century. The selection includes the legacies of different generations of poets, who lived and died in Russia, as well as émigré poets. It includes poetry that makes little or no use of traditional rhyme and meter, thus, students are immersed in varied poetic traditions, poetic styles, approaches, and forms. Each poet and poem are introduced with contextual notes and supplemental materials such as glosses, translations, and open discussions for both remote and hybrid classes.

Collaborative Project

This project was funded by a grant from the Geddes Language Center (CAS) and by UROP (University Research Opportunity Program). This project allowed me to work closely with an undergraduate student with experience in the digital humanities, Nadiya Prokopyeva, who, through the project, gained exposure to instructional design practices. The Geddes Language Center and the Center for Teaching and Learning collaboratively supervise different aspects of the design and maintenance of this online resource. For us as a team, it was important to create not only an OER, but rather to build a visually appealing library environment with materials presented in cross-sections, so that users might experience a given media content through words, sounds, and visual art.

Recordings

Hosting poetry readings on the BU campus became a longstanding tradition. Using their own poetry, contemporary poets such as Polina Barskova, Sergei Gandlevskii, Vera Pavlova, Katia Kapovich, and many others bring the understandings of the poetic tradition to bear on many of the great questions of existence, and questions revolved around what the poet meant in a poem. The Geddes collection in Russian Poetry and Prose features performances by authors over the past five decades. Media Resource Specialist Francis Antonelli at the Geddes Language Center digitized a fairly large collection of audio recordings of Russian Poetry and Plays that were previously only available on cassette or reel-to-reel tape, and created a channel where, in some cases, the original author’s voice can be heard. The channel offers digital versions of selected titles from this collection. Students have access to previously unavailable archival recordings of poetry performed by Anna Akhmatova, Bella Akhmadulina, Yevgeny Yevtushenko, and Andrei Voznesensky. For copyright reasons, the full recordings are not available to the general public, but if you are interested in gaining temporary access to any of these digital holdings, you can contact the Director of the Geddes Language Center Mark Lewis directly at mslewis@bu.edu.

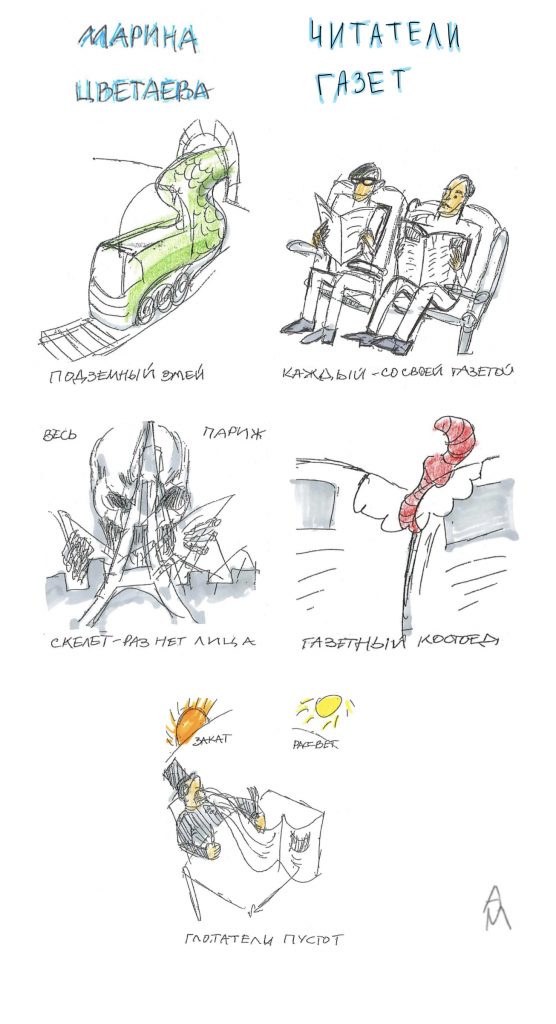

Bridging Poetry and Graphic Art

An innovative feature of this resource is the section called GRAPHICA (visual interpretations of the poems presented in highly stylized, simplified drawings done by a graphic artist). The drawings provide context clues, which help with the meaning of difficult vocabulary and understanding of the content. GRAPHICA presents complex metaphors and allegories in an attractive, emotionally appealing manner. Other aspects of the visual representation of figurative language is a hyperbolic rendering of emotions, dramatization, and entertainment that enhance poetic texts.

Key Components of the Project

The BIOGRAPHIES section includes short biographical sketches of poets to give the reader an abbreviated picture of poets’ lives within their social context and highlight their achievements.

POEMS pages bring the reader to the list of poets and their poems. Each poem is aligned with a piece of graphic art made by a heritage learner of Russian. We chose fairly short poems to make them approachable for students; they can play around with the formation of a poem and poetic language.

COMMENTARIES (ПРИМЕЧАНИЯ) on individual poems provide contextual clues to the meaning of the poem or clues to an emotional context that readers might miss when reading a poem from a traditional selection of poetry. Our project aims to re-introduce the most brilliant and imaginative Russian poetry to learners of Russian, so we pay particular attention to features of figurative language like rhyme, alliteration, meter, style, and allusions to other literary or historical figures or events. Commentaries make poems accessible for students by providing contextual information and helping students understand implicit messages that would otherwise escape them.

As mentioned before, the GRAPHICA section features visual interpretations of poems, which adds distinct advantages over standard digital poetry anthologies and provides a new dimension to the learning experience. In an age of increasingly visual communication, this format helps unlock the world of poetry and literature for a new generation of reluctant readers and visual learners. While reading a poem in POEMS, one can search GRAPHICA to find images that support the meaning of the figurative language in a line or a stanza. The drawings done by graphic artist Anthony Malykhin suggest a roadmap to unpack poems’ meaning and unlock poetic metaphors, creating with a single line an object, settings, or relationship. Graphic versions of poems are placed on separate pages, so the learners can experience the poetry in words alone, and compare their mental images and associations with the graphic artist’s choices.

Formative assessment for the digital space

BULB (BU Learning Blocks – a custom WordPress plugin) activities are instrumental in helping participants retain what they learn about the poems. Currently, BULB has six activity types: Multiple Answer, Multiple Choice, Matching, True/False, Fill in the Blank, and Calculated Numeric. To incorporate BULB into a desired page, a creator simply needs to add a block and the assignment will be embedded. This allows users to easily create an assignment page (as in our website) or conveniently place tasks in between blocks of text. BULB has a number of customizable settings that can determine how the assignment behaves, allowing the user to restart the whole assignment/quiz or simply start over when reloading the page. Additionally, BULB provides remedial, extended sets of exercises tied to the poems so that learners can independently complete tasks that would normally be too difficult for them in their face-to-face language course.

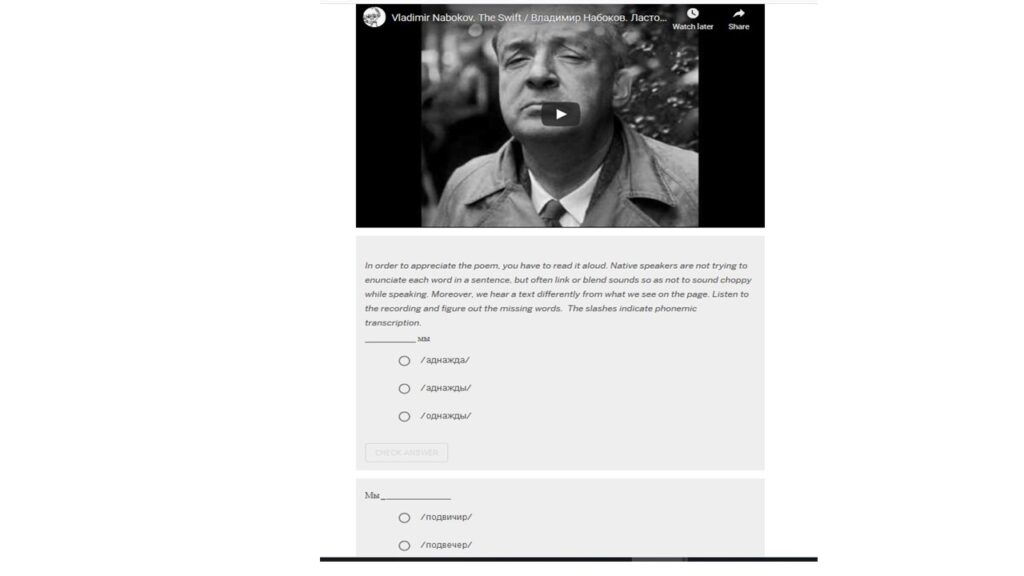

The LEARNING TOOLS section brings the user to a collection of exercises for learners to improve reading fluency and comprehension, expand vocabulary, and foster metalinguistic awareness through interactive, grammar problem-solving tasks. Most of the exercises and assignments offer “noticing tasks” to draw students’ attention to different problems in the areas of vocabulary, grammar, morphology, syntax, spelling, and pronunciation.

Exercises are purposefully designed to give students a chance to listen to a powerful reading of the poems while focusing on “noticing tasks.” Recordings lend themselves well to linking and blending activities since vocabulary is introduced in related clusters of words. As a result, students pay attention to the linking that usually occurs between a consonant and a vowel, and the blending that occurs between two consecutive occurrences of the same consonant.

Among other post-reading activities are tasks to figure out the omitted words in elliptical sentences and syntactic inversion that prepare students for noticing the relation between sound and spelling, meter and mood, diction, prosody, and rhyme. Thus, poetry becomes a visual and intellectual pursuit, which accompanies aural stimulation.

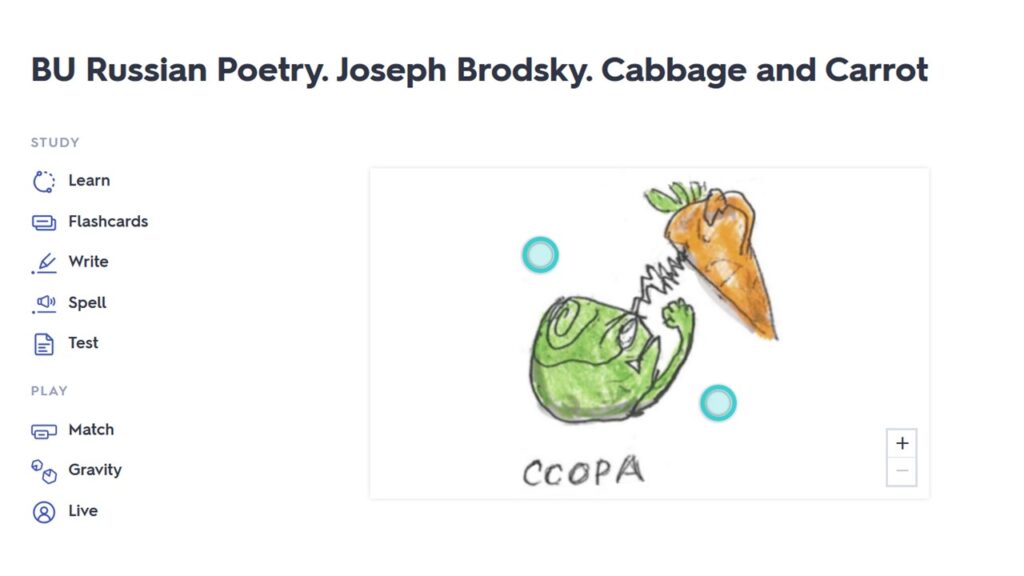

The site also features self-assessment activities related to the poems made with H5P and Quizlet. These kinds of activities include dragging text, matching games, interactive videos, flash cards, pairing games, and memory games with audio. Students benefit from these activities by being able to work on their reading and listening skills independently from a class, making them more autonomous.

We have also created a Language Animated Channel in our campus’s Kaltura mediaspace, where visually interpreted poems are turned into animations created with Video Puppet. This app allows converting Powerpoint presentations and markdown scripts to videos. The links are embedded in the LEARNING TOOLS page, with the idea that animation reinforces understanding and memorization by linking vocabulary words to memorable cartoons. We invite students to mentally create their own moving images or a cartoon. This is a process of translating a poem into one’s own language. We pose the question, “If this were your cartoon and you could choose a different image, what would it be?”

The site also includes resources for teachers.

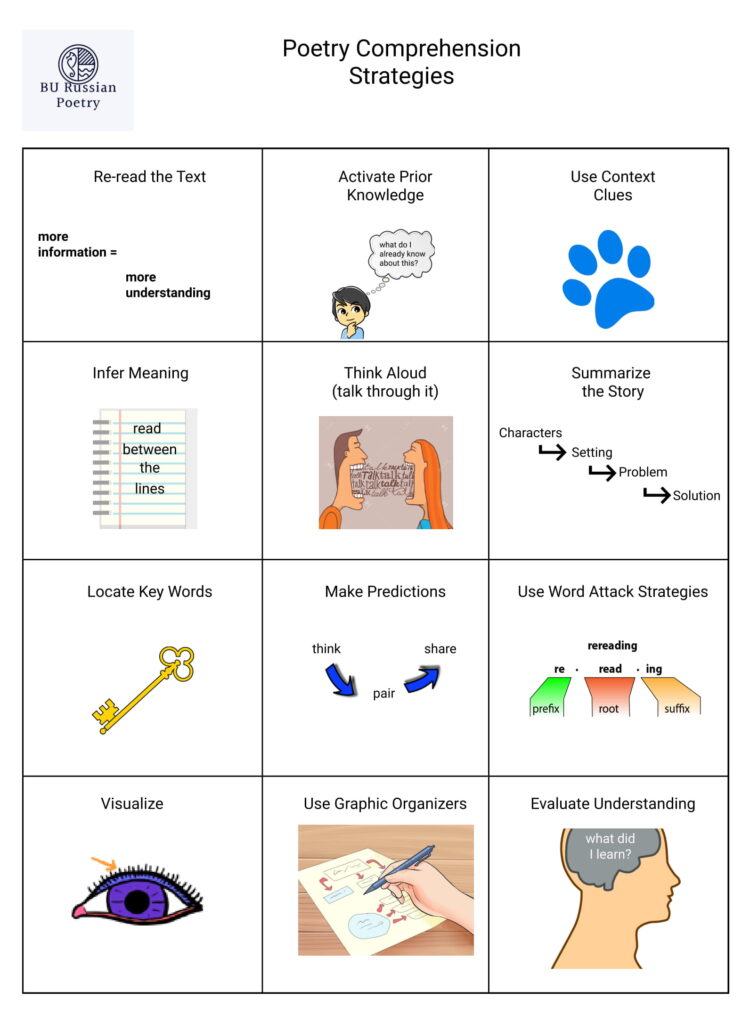

The POETRY ORGANIZERS section consists of lesson plans and materials to foster metalinguistic awareness and increase students’ linguistic knowledge. POETRY ORGANIZERS are used to work with figurative language. As poetry often conveys intangible feelings through allusion rather than direct description, students need support on multiple levels. We want learners to not only write with metaphors and similes – and to grasp the difference between the two – but also to understand the meanings of all their language options and use a variety of expressions with confidence.

We use POETRY ORGANIZERS to engage students deeply with a poem: to focus on choices of words; to identify literary devices used in poetry, such as metaphors, similes, rhythm, rhyme; to break apart a piece of poetry and understand it better, to discuss how well the images match the mood and meaning of the poems. In workshops, an instructor can ask students to “translate” a poem into their own voice. I find that if a voice of the poem interests readers or feels as if it might be a stretch, the assignment becomes all that more exciting.

The NAVIGATION TIPS page features ideas for platforms, lesson plans, and tips to apply visual art in language classes to cultivate students’ capacity to analyze and synthesize various forms of cultural and linguistic knowledge. A “true” individualized learning, or learner-controlled, environment would require the design of separate objectives and learning activities for each learner according to that individual’s own characteristics, preparation, needs, and interests. When students are learning using this digital resource, they learn how to develop their own definition for a word; how to make associations and connections between vocabulary words and their definitions; how to use the word in a new context, such as in personal note, an application letter, an essay, or a term paper.

In CLASSROOM, instructors can access the lesson activity instructions as well as ideas on how this digital resource can be used as a component of a language course, a literature course, or a course in Russian for Heritage Learners. Furthermore, curriculum connections, frequently asked questions and ways to apply BU Russian Poetry in language and literature classes can be found. One can find discussions on the real tricks of translation tasks or on creating a poem.

One strategy is to include poems that may confuse or frustrate students and not defend or explain the poems when complaints arise. Instead, challenge students with prompts like “Might the poem you dislike in the first place have been a response to something else?” This can help them develop a sense of literary history. Prompts like “If someone had joined the class today, would they get the joke?” are highly valued by students. Students often write parodies of the poems they dislike; these can have their classmates howling with laughter, and then they congratulate each other on their wit and sophistication. One of the things we particularly like about this exercise is that students engage and inhabit styles that they initially find idiotic. Consequently, these challenges become important factors affecting the feasibility of critical analysis of poems; and have created a community with new values they could not have anticipated.

The RESOURCES page contains links to comprehensive anthologies of Russian poetry and references to major scholarship cited in the commentaries.

Conclusions

Given recent interest in the use of OERs, key themes that emerged in a discussion of BU Russian Poetry could provide an understanding of the factors affecting engagement with this teaching model. It can lessen the burden of close reading of Russian poetry in a traditional classroom, and can also function as a stand-alone language module for students studying Russian independently. One of the biggest advantages of this resource is the flexibility of the overall design. This resource facilitates and supports students’ ability to visualize and understand complicated ideas, which is also a 21st century literacy skill. BU Russian Poetry acknowledges the variation between different students’ preferred learning styles and their willingness to adapt to new ways of learning. Learners observed that the model of OER itself influences and shapes their approach to learning. Finally, engagement with OER is underpinned by accurately informed and aligned expectations at the outset. BU Russian Poetry gives students the potential to surpass the limits of traditional classrooms and expand the student educational environment beyond the edges of their computer screens.