Language Learning and Identity: Helping Students Develop a Sense of Themselves as Second-Language Learner, Speaker, and Community Participant

By Deborah Cafiero, Senior Lecturer, Dept. of Romance Languages and Cultures, University of Vermont

During the pandemic, many educators, myself included, began to reexamine their priorities and pare their courses down to the most essential elements. In a course with diverse goals – increasing language proficiency, developing intercultural competence, enhancing student engagement, building a classroom social-learning community – which objectives could encapsulate the others? I decided to focus on the related goals of building a social-learning community and encouraging students’ sense of identity as learners and speakers of a second language, because I felt these two areas could help hold the class together and facilitate student learning in a time of crisis. Ultimately, the pandemic experience convinced me that these two goals should remain at the heart of my courses and that the path to other objectives can be built on their foundation.

What does it mean to feel a sense of identity as a second-language learner and speaker? Sadly, many students have already developed a sense of identity as a second-language learner, and it may not be the one we would want for them. Those who say they’re “not good at languages” have self-identified as inept learners in this unique field. But a positive self-identification as a second-language learner can lead students to feel empowered as effective communicators. And a sense of identity as a second-language speaker can help students feel more connected with different communities, more motivated to expand their range of communication, more empathetic towards those in different life situations, and more curious about cultures beyond their own.

Educators can take many measures to promote students’ sense of identity as successful second-language learners and speakers. In general these are the same strategies that promote successful target-language communication and a sense of community within and beyond the classroom, as well as a sense of connection between the target language and the student’s own life. In my view, the most important considerations are: A) to provide students with tools and opportunities for authentic communication, especially the opportunity to form social bonds in the target language; B) to encourage students to seek personal connections between their own lives and the material they are learning; and C) to use assessment and grading as a tool to encourage positive identity formation in the target language, not impede it.

In category A – tools and opportunities for authentic social communication – I place strategies such as:

- Opening synchronous classes with a “check-in” that not only includes recently learned material, but clearly serves to communicate personal information and form social bonds. For example, students and instructor can take the first few minutes of class to communicate personal impressions about the assigned reading or video, the semester, the pandemic, how their friends are feeling, etc. If the chat bar is used, a collective communication of personal feelings can happen quickly; if this experience is repeated over and over, students come to feel the social tie of the classroom in the target language.

- Providing an expanding list of socially cohesive vocabulary, expressions and linguistic practices. As Paul Toth and Ashley Shaffer describe in their presentation “Understanding Discursive Factors in Form-Focused L2 Peer Interaction” (ACTFL Annual Conference 2019), interaction among students in language classes depends on a host of factors including the desire to accomplish meaningful task completion in the target language, the attempt to understand and interpret instructional goals, negotiation over turn-taking and discourse direction, and enacting a classroom identity. Clearly students at the intermediate level and lower don’t have the proficiency to accomplish all these goals in the target language. However, the instructor can anticipate some of these needs and offer simple linguistic tools to help facilitate social interactions in the classroom: turn-taking phrases, simple expressions of apology, agreement and congratulations, strategies for making a polite request, etc. I offer different lists for different levels. At a novice level I provide a one-page list divided into “Expressions for the professor”, “Expressions for friends”, and “Expressions for an online class” (the last includes common technology issues such as “your microphone is muted”). Of course this facilitation still does not enable many students to handle social interactions completely in the target language, but it can jump start their sense of social empowerment.

- Arranging multiple opportunities for target language communication at different scales. With online classes at any proficiency level it’s important for students to have the opportunity to communicate as a whole class, for example during the “check-in;” to alternate the whole-class dynamic with breakout rooms; and to communicate in pairs or threes independently of the whole class, through partner chats. These independent communicative activities give students ownership of their target-language communication even at the novice level, but they need to be tailored for student proficiency. For example, native-speaker partner chats provide culturally meaningful conversations for levels intermediate or higher, but may be beyond the proficiency of novice students.

- Encouraging combined written and oral communication. The online modality offers nearly unlimited opportunities to combine writing with audio or video. For example, the chat bar can be used by the instructor while she speaks, or by students to facilitate their video partner conversations. Various language instructors have posted ideas for using shared written documents in breakout rooms to allow students to accomplish tasks through both writing and speaking during synchronous classes. These techniques allow students who are insecure in their oral abilities to exploit the affordances of writing/reading, and vice-versa. In addition, most students have already constructed an online identity that combines text, images, and video through social media. Incorporating this dynamic into the class facilitates the extension of students’ online identity to the target language.

- Modeling the tasks that students are asked to perform. The instructor provides the first example, not only of the linguistic structures that students will need to employ, but of someone in the class who takes social communication seriously.

In category B – personal connections between the material students are learning and students’ own lives – instructors can:

- Emphasize information exchange, reflection, and comparison over performance in most activities, and conduct reflection and comparison in the target language. Reflection and comparison take different forms depending on the proficiency level of the students. For a novice-level class, students can express likes, dislikes, and preferences, and use simple socially-cohesive constructions such as “I agree because . . .” For the intermediate high level, students can prepare extended reflections and solicit detailed comparisons from fellow classmates. Some important characteristics of this strategy:

- The instructor doesn’t present activities as primarily performance exercises (e.g., matching a particular grammatical structure with lexical items), but rather as a genuine desire to share information and impressions;

- The instructor should try not to prioritize grammatical accuracy over information sharing. That being said, increased accuracy over time is a curricular goal in virtually all higher education language programs and a personal goal for most students, and it’s difficult to achieve without error correction from the instructor. One approach is for the instructor to model accurate communication first – as mentioned above – and then give additional pointers after the conversation, without interrupting discussion. This makes it clear that while increased accuracy and precision are important long-term goals of language study, the proximate goal of language use is always communication with others and oneself. If the reflection/comparison is in writing, instructor feedback can first address ideas, only then pointing out frequent or significant mistakes.

- Include some element of reflection in most assignments. If the instructor doesn’t want to create an onerous obligation for students, they can grade reflections for thoughtfulness and leave out accuracy considerations.

- Encourage students to draw comparisons between authentic sources and their own experiences, again emphasizing the process of comparison over particular performance criteria. If asynchronous, use a tool that allows student-to-student communication such as a discussion forum, a shared video platform like Flipgrid, or a posting platform like Padlet.

In category C – using assessment and grading as a tool for positive target-language identity:

- Offer students some degree of choice in assessment. Students can be allowed to choose a topic for research, deliver a presentation live or pre-recorded, choose between readings in a written exam, etc.

- Design rubrics along a continuum, from grades based exclusively on communication and reflection, to those weighted more heavily for grammatical and lexical accuracy, with hybrid rubrics in the middle. The instructor can:

- Give meaningful weight in the course grade to assignments/activities graded completely on information exchange, communication and reflection;

- Avoid assessments graded exclusively for accuracy, without any grade component for communication. Language is always communication.

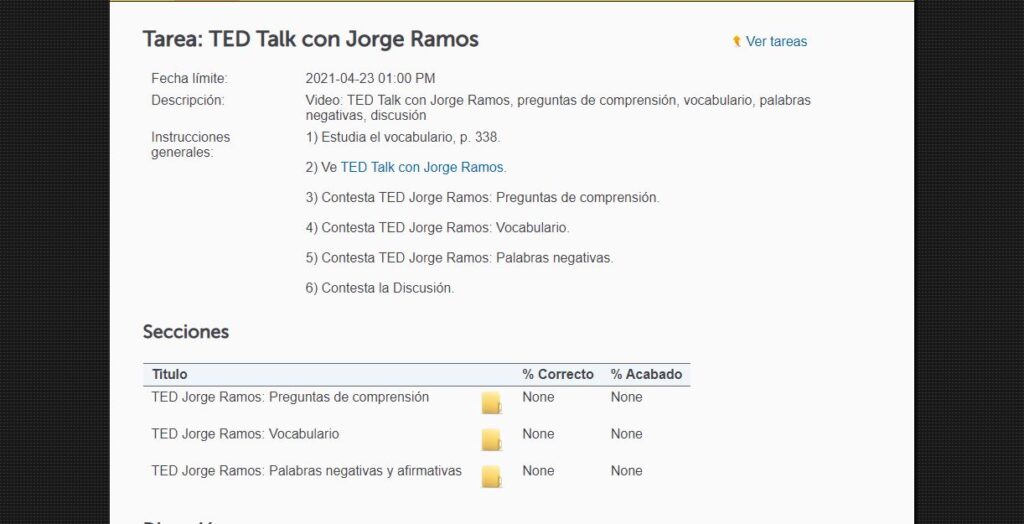

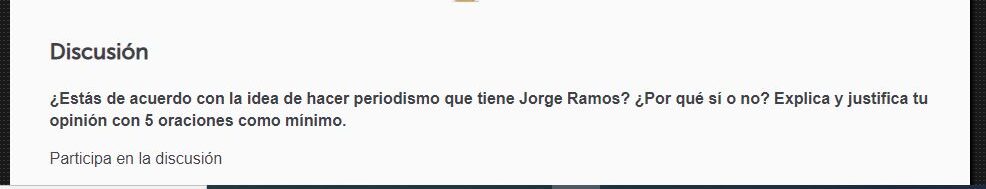

- Include different models for hybrid grading. I’ll share some assignment designs and rubrics from Intermediate Spanish I and II courses which I taught in the fall and spring semesters of 2020-2021, during the pandemic. One assignment combining “mechanical” exercises with a written reflection uses the website https://escolero.com/, a password-protected homework platform. Escolero assignments incorporate multiple-choice or fill-in-the-blank activities with a link to an authentic target-language source, and conclude with a discussion post. So while the “mechanical” portion of the assignment is graded for accuracy, the discussion grade follows a rubric based on textual understanding and original contribution.

The rubric for discussion posts in Escolero takes a simple approach to grading asynchronous communication by emphasizing thoroughness, textual comprehension, and originality:

3 – Excellent participation

- You have written an original response of the indicated length

- You have understood the text and the discussion question

2 – Fair participation

- You have written an original response but it’s a little short (3-4 sentences)

- You haven’t understood the text or the discussion question very well

1 – Poor participation

- You have written a very short response

- Your response is very repetitive of another student in the class

- You understood the text or discussion question poorly

0 – You receive 0 if your post suffers one of the following problems:

- You haven’t written a response

- Your response copies another student

- Your comment was written with an electronic translator

Students in these intermediate courses also post to a discussion forum in the learning management system (Blackboard). These assignments require more extensive writing based on an authentic target-language source, as well as responses to other student posts. The rubric for Intermediate I, shown below, includes a grade component for accurate comprehension of the source, but not for accurate target-language production. On the other hand, the degree to which the student tries to utilize recently learned material (encouraged/required by the nature of the task) does affect the grade:

Rubric for grading discussions in Blackboard

| 2 or less | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Task completion | Student did not complete all tasks described in prompt | Student minimally completed tasks | Student completed all tasks described but less amply | Student amply completed all tasks described in prompt |

| Comprehension of authentic text/video | Student didn’t refer to text or had poor comprehension | Student had significant misunderstandings | Student demonstrated fair comprehension | Student demonstrated good comprehension |

| Grammar and vocabulary | Student did not utilize recently learned vocabulary and grammar | Student responded with minimal use of recently learned vocabulary and grammar | Student responded with recently learned vocabulary and grammar | Student responded with thoughtful, extensive use of recently learned vocabulary and grammar |

| Response to other students | Student did not respond to other students | Student responded to 1 other student | Student responded minimally to 2 other students | Student had full, interesting response to 2 other students |

- In addition to designing rubrics that expand the concept of “accuracy” and measure different aspects of communication, the instructor can loosen the distinction between formative and summative assessments to underline the idea that language learning is a continuous process. Formative assessments allow students to improve their results through a process, which encourages the view that a non-native speaker may still communicate effectively and become a more effective participant in the target-language community over time. In the traditional distinction, formative assessment treats mistakes as an opportunity to learn, whereas summative assessment perceives mistakes as a defect that downgrades the final product. However, even a classic summative assessment like a unit test can have the effect of a formative assessment if students receive feedback and have the opportunity to correct errors.

- Encourage students to think of second-language speaking as a continuum, not as a continental divide between “native speakers” and “foreigners.”

- In Spanish, many U.S. residents are functionally fluent in the target language as L2 (for example, Supreme Court justice Sonia Sotomayor). Examples of such speech can be found in articles and interviews from U.S. Spanish-language journalism like Univisión. Give students the opportunity to hear such speakers communicating effectively in the target language as a second language. Students can take these speakers as legitimate models for target-language communication.

- As soon as possible, give students the opportunity to communicate in the target language with members of the target-language community. Depending on the circumstances, these interactions may be with foreign-born, native speakers (likely if students are using a language-exchange platform online) or with a mix of foreign-born and heritage target-language speakers if students are meeting with target-language communities in the U.S. Evaluate the interchange as a communication and reflection opportunity, not as linguistic performance. In my view, it’s important for students to feel a growing sense of access and connection to a target-language community through their language abilities. Over the course of repeated conversations, students realize that communication with target-language speakers is not all-or-nothing, but rather a growing relationship in which they can be relatively effective communicators and develop over time.

- Avoid unreasonable performance expectations that don’t correspond to the expected proficiency level. An authentic assessment of student performance shouldn’t demand complete accuracy in structural formulas rehearsed during class if they’re above the student’s proficiency level. (Classic examples in Spanish: the verb “gustar”, “si” clauses) Students expand their linguistic precision and expressive powers over time, and learning structural or lexical formulas for communicating complexity is part of the process. However, expecting students to extrapolate accurately from such formulas in order to communicate with a precision beyond their proficiency level tends to be demoralizing – it emphasizes what students cannot yet do – and conveys that the memorized formula is more important than meaningful communication.

The instructor can still draw students’ attention to errors. Most students pay attention to feedback on accuracy even when accuracy is not included in the rubric. Additionally, students can be encouraged to retake assessments after receiving feedback; they can often correct some level-appropriate errors after these have been pointed out to them.

Students can demonstrate some understanding of a concept – for example, by correcting errors when they’re pointed out – without being able to incorporate it into a linguistic performance above their proficiency level. This is part of the process through which students increase proficiency. They should be given the opportunity to engage without excessive penalties for committing level-appropriate errors.

The strategies outlined here are aspirational. I’m still working towards a system for encouraging students to develop a positive sense of themselves as second-language learners and speakers, in the context of ambitious proficiency and accuracy targets (essential for the departmental curriculum). I offer some observations based on our pandemic year:

1. I have not altered the course objectives, which are essentially performance objectives, for my language classes. In addition, the students and I recognize the importance of increasing accuracy and precision over time. However, I have adjusted my emphasis for both classroom activities and assignments, from achieving performance objectives to connecting and reflecting, as well as encouraging students to expand their sense of themselves as a second language learner, speaker, and community participant. Shifting my emphasis from performance to identity has led to some astonishingly inspirational student production and has not degraded students’ overall performance. When I have provided and modeled tools for students including lexical, structural, and morphosyntactic resources, they have used these resources to the best of their ability even when they were not being graded for accuracy. I have learned that I can trust most students to try to express themselves as well as they know how, without needing the motivational kicker of specific performance criteria for most activities. In the final assignment for my Intermediate I and II courses, where the grade was weighted significantly for accuracy, students matched the linguistic precision and sophistication of previous semesters during which a proctored midterm and final exam were administered. In evaluations from these courses, several students expressed appreciation for the assignments that prioritized communication over accuracy, noting that these allowed them to focus on their message and expression with less anxiety about errors.

The final assignment of the Spring 2021 semester for Intermediate classes involved a paper, not an exam, and spurred some of the most inspiring student work. In the final paper for Intermediate Spanish II, several students described hallmarks of positive identity and ownership such as: starting to think in Spanish during conversation, letting go of anxiety around mistakes, laughing and enjoying social moments with fellow students in the target language, and focusing on cultural interchange during the native-speaker conversation sessions. In the final assignment for Intermediate Spanish I, where students had to expand one of their previous Blackboard discussion posts, they chose different approaches which included: adding information with further research, expanding a personal post in a humorous direction, or linking their previous post more extensively to an interdisciplinary interest. The nature of the project allowed them to express their sense of themselves in the target language.

2. Students acknowledged that highly demanding communicative assignments – such as extended small-group conversations about complex topics, or partner chats with native speakers – were among the most difficult but also most valuable components of the course. As one student wrote about the native-speaker conversations, “In the first conversation, I couldn’t form sentences or maintain a conversation with my partner, but in the last conversation, the conversation flowed well and I enjoyed talking with my partner. Although I learned most from Conversifi [the online platform used], it was also the most difficult part of the course” (translation by author). The grading rubric depended entirely on information exchange, communication, and reflection, but students communicated with as much precision and accuracy as they could command. Comments revealed that students appreciated the importance of demanding, reflective communication for their learning process.

It’s difficult to gauge the degree to which positive student comments reflect a growing self-identification as a second language learner and speaker. I have not conducted either qualitative or quantitative studies that could demonstrate this association, and students themselves seldom use the terminology of identity in their (positive or negative) comments. There were students who wrote that they enjoyed the course and got a lot out of it even though they’ve “never been good with languages,” and a few who decided to change their major or minor to Spanish after taking the course. One first-year student decided to change his minor to Spanish after taking Intermediate Spanish I, because he realized that he actually could communicate successfully with native speakers of Spanish. Deciding to major or minor in a second language is probably a sign that the student has come to self-identify as a second language learner and speaker. I hope other students in the class have moved in the same direction, and that their experience will have a permanent effect on their sense of connection and curiosity for cultures beyond their own.

References

Toth, P. & Shaffer, A. (2019, November 22-24). Understanding Discursive Factors in Form-Focused L2 Peer Interaction [Conference presentation]. ACTFL 2019 Conference, Washington, DC, United States.

Love this. The focus is so often on vocabulary, grammar or pronunciation in the classroom and we forget all the other moving parts that complete the fluency puzzle. Great article.