Instagram vs. Reality: An Honest Look at Navigating a Classroom the Size of an iPhone

By Kaitlyn Teske, PhD, San Diego Padres

Education in Baseball

I have considered several new job titles during the pandemic: How To Download Zoom Coordinator, Instructor of It’s the Same Link Every Day, Guys, and Director of Unmute Yourself have been the top contenders. It goes without saying that the challenges set before teachers and learners that began in the spring of 2020 have been a roller coaster. For me, the onset of the global shutdown came at a time that is very significant in the world of professional athletics: Spring Training.

For those of you who may not be familiar, Spring Training is essentially the kickoff of the baseball season in the United States. All teams gather their major and minor league players and staff at their training facilities either in Florida, or in my case, Arizona. The month of March in baseball is the equivalent of the week before final exams in academia: no one takes a vacation, you buckle down and power through. So when word of COVID-19 around the globe began to spread, we all entered into Spring Training 2020 with a lot of apprehension. A few short weeks into the marathon month, everyone was told to go home. Baseball was off the table. Overnight, players and staff alike traveled back to their homes across the globe.

So why on earth am I explaining how Spring Training was disrupted in a magazine about education? No, I did not mistakenly submit my article to The FLTMAG instead of ESPN. I work at the intersection of professional baseball and education; my job is to coordinate the English language as well as the online high school programs for the San Diego Padres baseball club. To explain it simply, the players you see hitting home runs on TV are the tip of the iceberg in terms of the baseball world. All Major League Baseball (MLB) teams have what is referred to as a farm system. This system comprises several minor league teams across the U.S. and the Dominican Republic. Players work their way up through this system with the final goal of playing on the big league team (aka: the guys you see playing on TV). For example, the Padres have teams in the Dominican Republic; Peoria, Arizona; Lake Elsinore, California; Fort Wayne, Indiana; San Antonio and El Paso, Texas; and the big league team in San Diego, California.

For international players, particularly those from Latin America, it is common to sign with a team at a young age (typically 17 or 18 years old). A successful career in this system means a move to the U.S. as a young adult, and consequently English proficiency is a high priority for these athletes. In their professional careers these players will need English to speak to the media, to communicate with coaches and staff, and to navigate life in the U.S.. The Padres organization offers English classes at every level from our youngest players in the Dominican Republic all the way through to those at the major league level. We also have players who finish their high school degrees while working full time. In short, we are operating a miniature school within the larger baseball organization.

Now that you are caught up on the context, let’s return to the disruption of Spring Training in 2020. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, we offered face-to-face classes at all of our affiliates. Then, literally overnight, we shifted to a completely online model. I had teachers on my team who had never before taught online. About one percent of my learners owned a laptop or tablet. Many returned to the Dominican Republic or Venezuela, where internet connection is often unreliable and unstable. Everything I had planned for during the off-season and worked to strengthen in my previous seasons with the team crumbled around me. But, as all of us teachers and administrators know, the learners still deserved to learn.

Technology Driven Inequality in Education

Luckily, I had previous experience teaching online. I was familiar with Zoom and I had a few tricks up my sleeve (shoutout to the Arizona State University Computer-Assisted Language Learning [CALL] certificate program!). As I quickly shifted our program to an all online, Zoom-based synchronous class model, the inequality that the reliance on technology was creating for my learners was glaring.

Since the advent of CALL research, the idea that technology can create inequality in education has been evident (Gorski, 2009; Resta et. al, 2018). However, while this research acknowledges the digital divide (e.g., Rogers, 2001; van Dijk, 2006), it does not necessarily give us instruction on how to address it.

I suddenly found myself with learners I had never met face to face, whose only device was a smartphone, whose internet may or may not work on any given day, whose connection via a mobile hotspot on a bus driving through rural Indiana did not allow for fluid video connection, and who were sharing devices with siblings or roommates. My learners became frustrated quickly. I was frustrated as well. How could I make this season useful and impactful for them? How could I keep those with low technology access from falling behind? How could I engage them and let them know that their growth and education was still important to the team?

In searching for the answers to those questions, I found three main components in online learning that acted as major roadblocks on my players’ path to success in online learning. At the beginning of the chaos, I thought that because my teaching context is so unique, I was special and that these problems only applied to me and the education coordinators on other teams. However, in communicating with my colleagues in education outside of baseball I quickly came to realize that my situation was not unique. These were issues that many who were faced with the switch to online learning were dealing with while trying to keep the digital divide from widening.

Three Components of Online Learning: Expectation vs. Reality

The three aspects of online learning that seemed to be chipping away at the success of my program were devices, connectivity, and attendance. As I turned to the pedagogical literature and research, I continued to feel frustrated. It seemed that more often than not the information I found explained how to operate in an ideal classroom. No wifi issues, no constantly changing schedules, no global pandemic. It felt a little like that internet trend Instagram vs. Reality. You know, the one where someone posts a flawlessly posed picture and then when you swipe to the next photo it’s the dumpster fire that was the actual reality when the photo was taken? You know the ones; a cute photo of an Olaf the snowman cake next to the photo of the Olaf cake that looks like it was in an actual dumpster fire? The research was offering me Instagram and I was living in Reality.

This is not to knock research. Obviously it has its place and value in pedagogy and curriculum design. However, sometimes the theoretical ideas do not parallel the reality that we find in the classroom. It’s like my teaching interns have told me countless times in the past, “It wasn’t like this in the book in my Teaching Methods class.”

So here I offer you my personal take on the Instagram vs. Reality phenomenon in an online teaching context. Let’s call it Expectation vs. Reality.

Devices

Expectation: Students are connecting from a desktop computer or laptop with a stable internet connection.

Reality: Students connect from a computer, a tablet, or a smartphone. In my case, 99% of the time they connect from a smartphone.

This matters. In searching for tools to employ in my online classes and for resources to help my students be successful in this digital medium, we are bombarded with apps, software, and digital tools to include. They are all shiny and bright and new. I am yet to find any resources that first ask “What type of device do your students use to connect to class?” Let’s take Zoom for instance. So many of us have spent hours and hours talking to those little boxes that now house each student on our screens. It took me several weeks (an embarrassingly long time, I will admit) to realize that Zoom looks different when you log in on your phone versus on your laptop. I had been using only my laptop for Zoom. On a smartphone it does not automatically go to gallery view. By default, students only see one person at a time. If I share my screen with them, I become very, very small. The type of interactions that students have with each other and with the content on the screen becomes drastically different based on how they are viewing their digital environment.

If students are attending class from a smartphone, the other thing that I have come to realize is that most of these fun, shiny online tools are frustrating to them. They can’t have multiple tabs open. If they have to open up Safari on their iPhone, they lose the visuals of Zoom and now only have audio. These elements are crucial in choosing resources and planning lessons. Here is where we have to kick it back to old school, original CALL wisdom: if you can do it just as effectively with a pen and paper, do it that way. Technology in and of itself is not a pedagogy (Blake, 2013). Why would I add on the technological overhead of an online whiteboard application when they could just write in their notebooks and hold it up to the screen? No matter how long you have been teaching it is easy to get swept up in the whirlwind of fancy tools. My advice to you is to take a step back from the software or tool itself and first take a realistic look at the devices your students will use to access it. Will it add value or increase frustration?

Connectivity

Expectation: Students are able to connect at their designated class time each day.

Reality: Students are able to connect to their designated class time each day if they have a strong, stable internet connection and consistent access to a device.

I have never read an article or a teaching blog that mentions how to navigate a digital activity if your students have unreliable wifi. Our baseline, and erroneous, assumption in education is that students have stable connections; this assumption may come as a result of outdated thinking that presumes students who choose to learn online enter into that environment with the tools necessary to succeed. However, we have entered into an era where online learning is not always a voluntary choice on the part of the learner. The reality is that often students have poor internet connections and choppy sound or video. In my case, I frequently have learners who are playing baseball games on the road and will connect to class from weak, free hotel wifi or from a mobile hotspot on the team bus driving through the Texas countryside; neither of these situations make for great connectivity. Many students face a lack of a strong or stable internet connection even when they are at home due to economic reasons. The varying socioeconomic realities of our learners also lead to a varying range of internet quality.

So what happens when poor connectivity is a regular issue? Students are frustrated (whether they are the ones experiencing the connectivity issues or the learners whose class experiences interruptions due to a classmate with a poor connection). Teachers are also frustrated. The flow of your meticulously planned lessons is interrupted. Unfortunately, I do not possess the knowhow or the resources to personally attend to the wifi connections in my learners’ environment. What I can do for them is to take these regularly occurring connection issues into account when developing class materials and to have a backup plan. One of the most helpful workarounds for poor connections that I have found is to send any visual, audio, or video content to my learners before the class begins. Our preferred mode of communication for English classes is WhatsApp groups. If we are going to read an article or watch a video in class, I send it to the WhatsApp group beforehand. This allows for several things. First, in reflecting back on the previously mentioned issue of devices, my learners now have control to zoom in and navigate the material effectively on a small screen by means of a software that they are already comfortable with. Second, if there are any connectivity issues, usually the first thing that becomes problematic on Zoom is the video connection. This way, if students experience video interruptions, they already have the materials in front of them and are not reliant on the video feed to keep up with the class. Speaking of video feeds…obviously none of us enjoy teaching to small black boxes with learners’ names in them. That being said, if my choice is to teach to a little black box so that their audio connection is stable and they are not distracted by poor video quality or to teach to no one, I will take the little black box. Be flexible when it comes to your students having their cameras on.

My final tip in dealing with connectivity issues is the same advice I gave in considering students’ devices: consider this issue when choosing your tools and forming lesson plans. Those shiny new apps and software platforms may be appealing, but if you regularly have students struggling to even connect to Zoom, those extra bells and whistles may become an added frustration and hurdle to their learning, rather than an asset. While connectivity can be a major frustration for learners and educators alike, it can also lead to an even more difficult issue to deal with: attendance.

Attendance

Expectation: Students attend their classes.

Reality: Students attend their classes when their technology and circumstances allow them to.

If you are teaching in a context where students connect to class from a location outside of the four walls of your establishment, there are a myriad of circumstances that are out of your, and your learners’, control. They are at the mercy of their connectivity and devices, especially if your students are minors. Young learners have the devices and internet connection that are provided to them; we cannot expect middle schoolers to use their babysitting money to pay for faster wifi at home. Learners with low technology access often go hand in hand with poor attendance. As we all know, this is frustrating. It is frustrating for you as the instructor and frustrating to your student who now has to battle with feeling behind or lost in subsequent classes. Luckily (or maybe unluckily?) for me, these attendance issues were nothing new when the pandemic struck. In minor league baseball, players can move from one affiliate to another with only a few hours notice. Long road trips often interrupt the flow of classes. All this to say, I’ve developed some workarounds to help cope with the inconsistent attendance of my language learners.

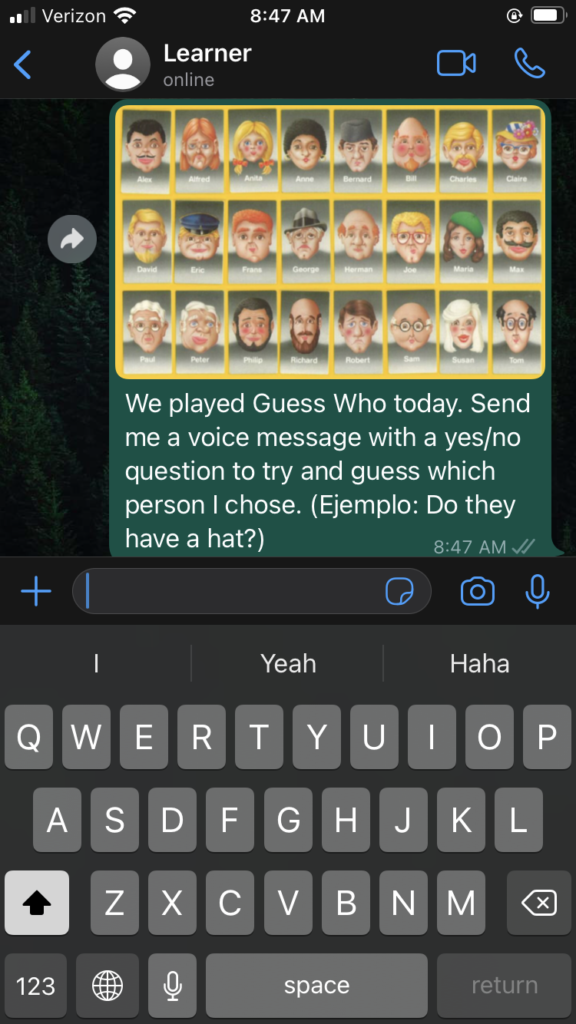

First and foremost: if disrupted attendance is a regular occurrence in your classroom, always have a backup plan. This does not need to be a completely separate lesson plan for every class. Rather, just as with the device and connectivity issues, incorporate this potential disruption into your planning. What is a small alternate assignment that could be done asynchronously to still include learners who are unable to attend that day? I suggest making these alternatives as low-tech as possible, especially if one of the most common reasons for absences is technology-related. As I mentioned previously, we use WhatsApp as our class group communication tool. When learners are unable to connect to class, I send them voice memos, photos, or videos via WhatsApp that include the content from that day’s class as well as a request for some form of interaction with them in the target language. This could be as simple as answering a few questions in written format via text or a quick asynchronous voice message exchange to practice the lesson’s target structures.

|

|

|

As Duncan and Young (2009) remind us about digital learning: consistency in structure is key. This is not to say that every class should look exactly the same. However, if the bones of the lessons follow a similar flow, I find that it is much simpler for students to receive the materials they have missed and to fill in some of the blanks themselves. For example, I begin every single class with five new vocabulary words. My players know that no matter what affiliate they are at, no matter what level they are in, the class will begin with those five words. So when someone misses class and I send them a screenshot of five words, I no longer need to explain what they are or why I am sending them. They instantly recognize that those are the day’s vocabulary words.

The final piece of the puzzle in keeping learners who miss class engaged and connected is a follow up. After they miss a class, I always send an individual message to check in. In those messages I ask why they missed class, ask if there’s anything I can do to help them connect more consistently, and assure them that I am sending all of the materials so that they can pick up where we left off in the next class. In my experience, these follow up messages help learners avoid the downward spiral of absences. One or two absences easily lead to more when they feel behind or lost. In addition, it helps to build rapport with learners when their absences are addressed as a sometimes unavoidable reality and not an infraction worthy of punishment.

Where do we go from here?

Addressing the issues of devices, connectivity, and attendance with a realistic lens has been immensely helpful in the past year and a half for my organization. While the research and literature available on digital language instruction has a critical role in the field, there is also a dose of teachers’ and learners’ realities that is often missing from the data. As teachers, coordinators, and administrators on the ground in the diverse field of education, it is our responsibility to conduct a near constant needs analysis in order to meet the needs of our unique population of learners and to ensure a meaningful and effective educational experience for them, in or outside of a physical classroom environment.

References

Blake, R. J. (2013). Brave new digital classroom: Technology and foreign language learning. Georgetown University Press.

Duncan, H. E., & Young, S. (2009). Online pedagogy and practice: Challenges and strategies. The Researcher, 22(1), 17-32.

Rogers, E. M. (2001). The Digital Divide. Convergence, 7(4), 96–111. https://doi.org/10.1177/135485650100700406

Van Dijk, J. A. (2006). Digital divide research, achievements and shortcomings. Poetics, 34(4-5), 221-235.

Excellent article; thank you so much for publishing it. Your teaching context sounds fascinating and your learners are lucky to have you! The advice you’ve given (keep it as simple as possible; post materials ahead of time; be flexible) is excellent for ANY teaching circumstance, in person or otherwise. Thanks again! ~Margot