Implementing Gameful Activities in an Online Class

By Alona Kladieva, PhD student, SLAT, University of Arizona

DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.69732/ADRN5646

Introduction

A classroom buzzing with excitement, where learning becomes a captivating adventure and students embark on thrilling quests to unlock language mysteries. This sounds like a perfect image of a language classroom, right? This is the world of immersive gameful environments that has been capturing the attention of educators all across the globe. From enhancing motivation and collaboration to encouraging social interaction and language awareness, games are transforming the way we teach foreign languages. Verified by compelling research, game-based learning has demonstrated to be a powerful tool, providing students with agency, a sheltered space for practice, and an unforgettable educational experience (Reinhardt, 2019; Reinhardt & Thorne, 2020; York, 2020).

It takes certain knowledge and understanding of principles of gameful L2 teaching to design and implement games in the classroom. In this article, I will delve into the key factors that make a game captivating and productive, and will talk about my experience implementing educational games on Zoom. I will explain the rationale behind implementing gameful activities with adult immigrant English learners, delving into the benefits it offers. It will further discuss the challenges encountered throughout the process and conclude by showcasing how gamified learning can transform students’ outcomes of the language learning process.

Teaching in an online environment

Teaching online has become much more widespread since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. This format continues to dominate the realm of remote learning, presenting language teachers with specific challenges and the need for considerations. Here I will present my recent experiences working with a nonprofit organization called Literacy Connects, which helps immigrants learn English and improve their language skills with a focus on communicative competence.

Last semester I worked with adult immigrant students from Mexico, Brazil, and Chile who have been taking ESL classes on Zoom twice a week over the course of 16 weeks. The students had Intermediate level proficiency and were able to engage in daily interactions, but aimed to expand their vocabulary and knowledge to be able to engage in broader conversational discourses like job communication or interactions with their kids’ teachers. The classes lasted for 90 minutes, so naturally, my challenge was to keep the engagement up and promote interaction and collaboration amongst my students. In an online synchronous class, it seems harder to do since there is no personal physical interaction, snack breaks, or small talk face to face.

While trying to find ways to make online classes more involving and interactional, I thought of introducing gameful learning to them, being aware of its benefits for collaboration and engagement, but I almost instantly faced certain challenges: students used smartphones and had limited digital literacy skills. If you have ever joined a Zoom meeting from your smartphone, you know that it can be difficult to see the screen and other participants’ faces at the same time, or navigate the chat window. This is the very challenge that my students and I had faced during our online classes. To address those issues, I made sure that when I shared the screen with the activities I zoomed in as much as possible to maximize readability. For these particular gameful activities, I ensured that students did not need any supplementary materials to be shared in advance, because it would take additional time for them to download any handouts and be able to find them on their phones. In this setting, I was not able to remotely help students navigate their devices during class time.

One of the biggest challenges was making sure that all students are involved and participating equally. For that, I put them in breakout rooms when giving the task of the game and also used the chat feature whenever students could give quick short answers. Next, it was important to make sure the activities on screen were visible to my students who used smartphones. For that, I used bigger fonts and no animations wherever they were not necessary. I made instructions more clear by breaking them into smaller sentences and showing the visuals along with modeling the activity.

When implementing the gameful activities, I utilized principles for effective MALL (mobile-assisted language learning) design, including guided activity, reflection, feedback, pacing, and pre-training (Moreno & Mayer, 2007). One of the most important principles is that the design should focus on pedagogy, instead of technology (Ting, 2010), meaning that the games should be purposeful and not just fun. I connected the topics that we studied over the course of 16 weeks, and made sure that students needed to use active vocabulary and grammar to achieve the goal of the game.

Gameful Activity Types

A Random Question

This activity could be used as an icebreaker so that students get to know each other, or it can be done in later classes. The teacher puts some interesting questions on a picker wheel online before class, and in class the teacher “spins” the wheel and students take turns answering the questions.

The questions include:

- Favorite movie

- Favorite sport

- Favorite snack

- Favorite season

- Something I would like to learn more about

- Something I do to stay healthy

- Something I would never eat

- Something I like to do in the summer

- Something I am proud of

- Something I know about penguins

These questions could be altered to learners’ language proficiency and the topics that have been covered in the classroom. One such adjustment may be incorporating superlatives into the sentence “Something I am proud of” to make it “Something I am most proud of.” Another effective addition to this game that I tried with my students was to ask one person to build a full question using a given prompt and ask a classmate. For example,

Student A: What is something you are proud of?

Student B: I am proud of my family.

It might seem like a small modification, but it is important for English learners to practice building questions and this particular example requires students to change the “I am” structure in the statement to “you are” in the question. It may also provide students with the insight that the same question may be asked differently. They may ask “What is something you are proud of?” or “What are you proud of?”

When played in the physical classroom, this game may or may not require using the screen, the teacher can just cut the pieces of paper, write questions on them, shuffle them and put them in the hat or the box. But when played online, sharing the screen is the only option, and the instructor should make sure that the words are easily visible to the students.

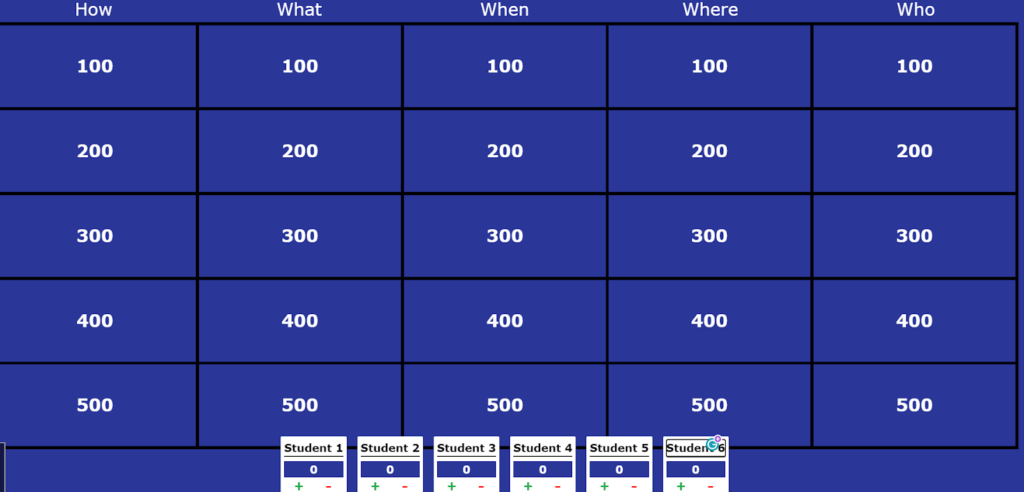

Jeopardy!

The teacher prepares 5 categories of questions and 5 questions for each category. There is a free website that allows you to build your own Jeopardy game (click to access the example used in class). A teacher can divide students into 3-4 groups and assign students the group names – e.g. Group 1, Group 2, etc. Most of the online video platforms have an option to change the name and the teacher can either rename students’ names by adding a group number to their names, or asking students to do it for themselves. This decision is up to the instructor and will depend on how familiar students are with digital technology or a specific platform. This naming step might not be necessary in the smaller classes; however, with a bigger group of students it may help the teacher to keep track of students in each group. Then the teacher chooses how many groups will participate in the game, and when a group of students gets the right answer, the teacher adds the points to the group.

Before starting the game, explain the rules to your students: each team takes turns selecting a category and a point value. The teacher then reads the question aloud, and the team must answer within a set amount of time. If the team answers correctly, they earn the point value of the question. If they answer incorrectly, the other teams have an opportunity to answer the question and earn the point value.

When looking at the steps of implementing this game, it becomes clear that the instructor has one too many tasks to take care of, so instructors may just need to embrace this and be prepared for some extra preparation time if they are planning to incorporate games in their teaching. Another way to deal with this is to know your students really well and to be confident in delegating some of the tasks to them. Just like with the previous example, where the teacher may ask students to add the number of their groups to their names, they may also assign one student to add point values to the groups when they win. In this case, the link to the website should be shared with the student and they should be able to share their screen, which may be quite challenging for some students. Knowing their digital proficiency and their access to technology helps a great deal during the preparation process. When working in an online classroom, in my introductory lesson, I ask students to fill out a Google Form survey where they let me know which device they use to join the class, and select options of what they are able to do with the technology such as:

- I know how to connect to my class

- I know how to mute / unmute my microphone

- I know how to start and stop my video

- I know how to share my screen

- I know how to open the link if shared in the chat

- I know how to share the link in the chat

- I know how to navigate a website

As one of my last questions, I ask whether students would feel comfortable helping me in the class and list out some of the helping tasks they might do, such as share their screen, share materials in the chat and ask students if they were able to access it, etc. Preparing such a survey and then keeping students’ responses in mind may take some time, but in the long run it allows the teacher to delegate some of the smaller tasks and also empowers students to use their digital skills and be more active in the class.

20 Questions

The teacher thinks of a random character, but does not tell who it is. Students can ask questions to guess the character, but the teacher only answers “yes” or “no”. Whoever guesses the character, can take the role of the “character”, and other students will ask them questions. This game can be adapted to the studied topic like “guess the food item” or “guess the object”. Otherwise, it can be simply played as a warm-up or a break from main lesson activities.

Word Chain

The teacher / student says a word on a particular topic e.g. “food”, the first person says the word “apple”, the next student says “egg”. Apple —> egg. The second word should start with the last letter of the previous word. It is more efficient if the vocabulary is connected to the topic of the lesson. Again, in an online classroom, the teacher will have to share their screen and preferably write the words down as students are saying them one by one. Some video platforms allow users to use the whiteboard. In other cases, the teacher can just use a blank document, zooming in the font.

Story Chain

The teacher starts a story by saying: “Yesterday I went to the movies. My friends and I saw Titanic. I have seen this movie five times.” Each student continues the story, using sentences with verbs in the past simple and present perfect. This is the activity that was used in my class when we studied the difference between these verb forms, but it can be easily adapted to different active grammatical structures or vocabulary. For instance, to practice second conditionals, the teacher may start by saying: “If I won a million dollars, I would buy a penthouse and a yacht.” and the student continues: “If I bought a penthouse and a yacht, I would invite all my friends to see them.” Given enough time, it would be helpful to write these sentences down similar to the previous activity. That way, students have visual clues along with practicing listening comprehension and have more chances to learn a target grammatical structure.

Idiom Charades

The teacher prepares slides with visuals and idioms that relate to the topic of the lesson (e.g. body idioms, food idioms). Then the teacher shows the pictures containing the idioms and students try to guess its meaning. When students guess the idiom or if it takes too much time and students have put in some effort, the teacher proceeds to explain the idiom and how it can be used, giving some example sentences.

When I looked for pictures for idiom charades, I ensured that the images are as realistic as possible. I was inspired by the discussion raised in one of the Literacy Connects training (a nonprofit organization that provides free lessons for immigrants), where the ELAA training coordinator, Kate Van Roekel, showed examples of different images of apples and mentioned that some of our students might not be familiar with other shapes of drawing an apple or may not understand what we mean when we show the Apple smartphone. I found it to be true for my classes and now whenever I am looking for some pictures, I purposefully select realistic photographs.

Students’ Feedback and Conclusion

All of the students found these educational games fun and useful. They pointed out that learning through games made the process of acquiring vocabulary more engaging and facilitated vocabulary retention. From their feedback, I gathered that gameful learning approaches engages the heart as much as the mind, leading to increased motivation and accelerated progress.

I was thrilled to find such inspiring feedback from my students and this positive energy encouraged me to work harder on finding solutions to the challenges described above. These 16 weeks showed me that everything is possible if you have a purpose in implementing new teaching practice and awesome students to work with.

Despite careful lesson planning and trying to foresee potential difficulties, I faced some challenges, including accessibility of the screen, keeping my students engaged, and collaborating and allocating the right amount of time among others. For accessibility purposes, I did not use any small windows and simplified the navigation for my students. In this case, I had to be the navigator as my students used smartphones. Oftentimes, implementing the games took more time than I would initially allocate in my lesson plans. It helped to add more time to all the game activities, considering some technical issues and addressing students’ questions. In order to keep my students engaged and motivated, I put them in breakout rooms and asked them to use the chat feature when they would need to give brief answers.

When I was implementing gameful activities, I came to realize that gameful learning does not necessarily have to be high-tech with advanced technology. In my Zoom classes, students did not have a lot of resources such as technology or digital skills, and it was still possible to help them learn through educational language games.

References

Moreno, R., & Mayer, R. (2007). Interactive multimodal learning environments: Special issue on interactive learning environments: Contemporary issues and trends. Educational Psychology Review, 19, 309-326.

Reinhardt, J. (2019). Gameful second and foreign language teaching and learning: Theory, research, and practice. Palgrave Macmillan.

Reinhardt, J., & Thorne, S. L. (2020). 17 Digital Games as Language-Learning Environments. Handbook of game-based learning, 409.

Ting, Y. L. (2010). Using mainstream games to teach technology through an interest framework. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 13(2), 141-152.

York, J. (2020). Pedagogical considerations for teaching with games: Improving oral proficiency with self-transcription, task repetition, and online video analysis. Ludic Language Pedagogy, 2, 225-255.