Hacking Your LMS: Making Ungrading More User-friendly

By Andie Faber, Kansas State University, and Christina Beaubien, Westfield State University

DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.69732/AWKC4667

Have you Heard of ungrading? All the Equitable Kids are Talking About It!

An ungrading approach can increase equity, draw students’ attention to feedback, and bolster intrinsic motivation in the language classroom. However, taking this approach produces obstacles within a Learning Management System (LMS) that is designed for grades. The advantage of the LMS is that it allows instructors to provide students with feedback and gives students the flexibility to track their progress electronically. However, once you take away the language of grading (i.e., letter grades and percentages), the LMS falls flat as a feedback resource. Here we will provide you with some useful ‘hacks’ to make your LMS more ungrading friendly. First, let’s get a better understanding of traditional grades versus ungrading, and why it’s so important for the language classroom.

What is ungrading?

Although alternative grading practices have been around for a while, educators have often had to individually address the pitfalls of traditional grading to find options that support their students’ learning. In 2017, the term ungrading (Blum, 2017; Stommel, 2017) emerged as an umbrella approach to catalog a variety of practices where the overall goal is the same: to shift focus away from metrics and recenter attention on learning. As Stommel (2023) explains:

“There is no neat and tidy thing we can all do tomorrow to obliterate grades. […] I’ve repeatedly defined ungrading as ‘raising an eyebrow at grades as a systemic practice, distinct from simply ‘not grading.’ The word is a present participle, an ongoing process, not a static set of practices’” (para. 2).

Some of the common themes of the ungraded classroom include providing more autonomy, encouraging metacognitive practice, ensuring transparency around pedagogical decisions, and focusing on feedback. Granting students opportunities to participate with creating or directing the objectives of the course allows for more flexibility and provides an environment for student investment, and therefore more intrinsic motivation to learn. In order to achieve those goals, ungrading often ties the learning objectives to specific industry or professional standards. By inviting students into the discussion around pedagogical choices, ungrading makes it clear how each step of the process will lead to meeting the required standards – and how the standards relate to their personal goals. In this regard, each classroom redefines success outside of the traditional academic setting (an environment steeped in prejudice), and students learn to track their own progress against professional standards as opposed to comparing themselves against each other. For this reason, ungrading not only hyper-focuses on the feedback to students, but often encourages students to resubmit their work if they don’t meet the previously outlined standards. Essentially, the shift away from metrics allows for assessments to become a part of the learning process.

So, what are the issues that an ungrading approach addresses?

The implementation of traditional grading practice in the early 20th century was established within the context of industrialization as a way to standardize learning results. However, even since its inception, there has been consistent criticism regarding its efficacy (see Brookhart et al., 2016). In the mid- to late-20th century, this skepticism was confirmed when researchers began reporting empirical evidence that grades have a negative impact on learning outcomes (e.g., Butler, 1987). The research that has been conducted over the years indicates that traditional grading practices:

- encourage competition over collaboration;

- fail to provide meaningful feedback to students;

- offer a fixed point for attainment that does not reflect growth;

- perpetuate systems of privilege and oppression;

- discourage risk-taking and growth mindset;

- reward compliance over learning and inquiry;

- undermine linguistic diversity and inclusivity;

- uphold a monolingual bias (i.e., dual-monolingualism over multilingualism).

As Alfie Kohn (2011) succinctly put it, “Research shows three reliable effects when students are graded: They tend to think less deeply, avoid taking risks, and lose interest in learning itself.” From an equity perspective, traditional grading upholds standards that are rooted in oppression and that impede the open and free dialogue between student and professor (hooks, 1994). Grading often ranks and rewards individuals on their ability to achieve standardized (and sometimes arbitrary) benchmarks regardless of their initial capabilities, thus ignoring the systemic inequities that result in an uneven playing field. This makes ‘trying your best’ an impossible reality for many students from marginalized communities.

Many ungrading educators prefer to adopt systems that separate the evaluation process from the grade. For example, ungrading pedagogy often encourages hacking assessments (Sackstein, 2015) by focusing on alternative assessments (Kohn, 2011), process letters (Stommel, 2023), or portfolios (Stommel, 2023) to evaluate students via industry or professional standards. Another strategy is to rethink the entire structure of the classroom by first considering the types of assessments needed to meet professional standards, designing the course content accordingly, and then adopting specifications grading (Nilson, 2015), labor-based grades (Inoue, 2019) or contract grading (Davidson, 2020). These methods measure how much work the students complete ‘at level’ and then have a specific grade correlate to a specific amount of labor. Regardless of methodology, since one of the defining factors of ungrading is the focus on feedback as opposed to the actual grade, ungrading educators often redefine how they evaluate students by creating a language that both circumvents the triggering and conditioned effects of the traditional grade (i.e. A-F or 100-point scale) while also highlighting the importance of feedback.

What does this mean for the L2 classroom?

The same issue of equity is on stark display in the language classroom, where students’ experience with the language can vary wildly; these multi-level classrooms are becoming increasingly more common, particularly at smaller institutions or for less commonly taught languages. Traditional grading practices are ill-equipped to fairly evaluate students with such disparate experiences in a way that reflects their growth and learning. Students who begin the course with stronger language skills tend to finish the course with higher grades (no surprise) – but do they put in the same energy and effort as students who have little to no experience? Have they undergone the same degree of growth?

In developing 21st-century global citizens, our priority as language educators should not focus on whether or not a student can conjugate a verb in the present tense or use the subjunctive in the appropriate context – grammatical accuracy isn’t a deciding factor in whether or not the student can communicate effectively or navigate a conversation. Nevertheless, grammatical error correction is often the primary type of feedback that language students receive within traditional grading systems. Not only is this type of feedback questionable in its efficacy, it perpetuates the myth that there is a single “correct” way to use the language – ultimately promoting a kind of dual monolingualism rather than supporting the development of multilingual students. Although it’s been over 30 years since François Grosjean warned that “the bilingual is not two monolinguals in one person”, we still struggle to accept natural bilingual phenomena in the language educator community. In essence, we should be focusing on building cultural and linguistic competence that mimics real-world contexts, rather than focusing on specific grammatical errors, so that we can better support emerging multilingual speakers and more effectively push back against standard language ideologies that assert that there is only one correct way to speak a language. Because ungrading pedagogy redefines success as meeting standards as opposed to punishing mistakes, and because those standards are often based on building cultural competence and linguistic diversity, language learners have less fear engaging more deeply with the learning process in the target language while also developing positive attitudes towards multilingualism.

In addition to the diversity in the amount and quality of previous exposure to the language, individual factors, such as motivation, aptitude, anxiety, and attitudes affect the language acquisition process. L2 acquisition research demonstrates a positive correlation between intrinsic motivation and successful language learning outcomes (e.g., Gardner, 2007); conversely, anxiety exhibits a negative impact on language learning; yet as we mentioned above, pedagogical research indicates that grades induce anxiety and stifle motivation. What’s more, grades inhibit risk taking (e.g., Butler, 1987), which is imperative in language learning as students need an opportunity to formulate and test their hypotheses about how the language works. If they are concerned about producing the ‘right answer’ or following specific classroom protocols in order to ‘get a good grade’, their attention is drawn away from learning. In this way, grades often serve as a motivator for behavior, rather than for learning, ultimately demotivating students from becoming life-long learners by undermining the innate curiosity we develop as children. Overall, this often leads to less interested and less engaged students (Blum, 2020).

Language acquisition is an individual process that follows a non-linear path. Language itself is a diverse and dynamic communication system comprising a myriad of dialects, sociolects, and idiolects. Traditional grading systems are, quite simply, not equipped to reflect these realities.

Being an Ungrading Educator in a Grading World

How do we implement ungrading? What are some options?

Okay, you’re officially on the ungrading train, now what? How do we engage L2 learners in a way that is equitable, that ensures empathy building with other cultures and communities, and that forefronts communicating as a primary goal? The research indicates that traditional grading actively stops us from achieving those goals, but how do we choose our ungrading adventure? In our courses, we like to focus on three concepts:

- Metacognition: The term metacognition refers to ‘thinking about one’s own thinking’. Research (e.g., Feldman, 2019) finds that regularly engaging in metacognitive practices allows one to obtain information more efficiently and evaluate the productivity of thoughts and actions. To encourage metacognitive practices among our students, we regularly ask them to respond to questions that focus on: (i) awareness (e.g., What did I learn?); (ii) process (e.g., How did I learn it?); (iii) evaluation (e.g., What did I do well? What was difficult? What aspect of my learning am I most proud of?); and (iv) development (e.g., How can I improve? In what ways will this knowledge / skill be useful to me in the future?). We ask these questions in both informal class discussions and more formal reflection assessments, such as self-evaluations or weekly participation blogs where students evaluate their language use and contact.

- Collaboration: Teamwork is an important 21st-century skill, as are critical thinking and evaluation abilities. By inviting students to participate in the discussion of how their work will be evaluated, they refine these important skills and develop a heightened awareness of assignment expectations, because they helped to create them. This can be accomplished not just through collaborative rubric workshops or peer-review, but also by having student-led units and/or activities. It could also be as simple as asking students to source real-world materials that perhaps reflect their lived-experiences.

- Autonomy: Research (see Pink, 2009) indicates that the number one factor in intrinsic motivation is feeling in control. If we truly want to foster autonomy amongst our students, it is imperative to provide them with the freedom and flexibility in the classroom to make decisions about the what, how, and why of their learning. This is somewhat accomplished through metacognition and collaboration, but we need to go a step further. For example, if a student speaks Spanish at their work every day, you could ask them to keep a reflection journal that compares what they’re experiencing at work to what they’re learning in class. Being flexible about what counts as class credit is crucial to ungrading.

Providing students with ample opportunity for self-reflection in class and in their coursework, engaging them in the evaluation process through peer evaluation and collaborative rubric development, and offering flexibility, allowing students to make decisions about how they demonstrate their learning, all helps to draw learners’ attention to the learning itself. Through using narrative feedback or other visual markers not rooted in points, percentages, or the A-F scale, students are released from the burden that these traditional grading systems carry. This also allows us to separate feedback from the grade. In our system, feedback is not used to justify a grade, as one student recently reflected, “I was receiving feedback on how I performed rather than why I lost points”, which they indicated as positively motivating.

How do we maintain rigorous standards and stay organized via ungrading?

Contrary to popular belief, ungrading isn’t just total anarchy and classrooms aren’t free-for-all learning spaces. Most students enter into the classroom expecting some level of organization and expertise on the part of the professor. Simply removing all grades from assignments won’t work. We need to redefine the language we use for evaluating students by focusing on meeting standards while still allowing for (read: not punishing) mistakes.

A simple way to redefine the language of grading is to use a sliding scale of ability (outstanding, sufficient/meets standards, and insufficient), or even of emotions (i.e. ‘Rate your ability to describe yourself in Spanish on a scale of happy face to sad face’), coupled with descriptive feedback that focuses on abilities and skills being developed in class. Student focus should be on using the feedback rather than just seeing they’ve done well and then chucking the document into the trash bin. Visual markers, like check marks or emojis, signal completion of work without triggering the language of grading. Of course, those visual markers work best when you’re able to physically write on the things you assign. So, how do we respond in a digital age where LMS rule (or maybe wreck) your life? Have no fear, we’ve got a hack for that.

Ungrading: an LMS Nightmare

Even if you’re in a loving relationship with your LMS, you’ve probably realized that there are some drawbacks to such rigorous, electronic standardization. In this way, the LMS becomes the first hurdle towards maintaining organization while also stepping away from metrics. Basically, even if the evaluation settings are numerous, they are still limiting.

The challenge: You want to evaluate students’ projects based on collaboratively defined standards but you don’t know how to grade that in the LMS.

The problem(s): In most LMS, the grading and display options usually include: Percentage, Points, Complete/Incomplete, Letter grade (A-F), GPA scale, or Not graded. These options all present problems to the ungrading approach. For example, percentage, points, and letter grades are all typical manifestations of the traditional grading system, which come with years of baggage that we attempt to shed in an ungrading classroom. We want the students to focus on the feedback, not the grade. Additionally, although most LMS have an “ungraded” option, the system tends to interpret “ungraded” as “unevaluated”. This often erases the assignment from the gradebook or to-do list. Students have difficulty finding their submissions to get their feedback, and the system doesn’t signal when the assignment has been missed. Likewise, some students interpret “ungraded” as not forming part of their overall evaluation (read: optional).

The solution: We recognize we need a new grading language that incorporates visual markers, but we struggled with manifesting this in the LMS. It turns out that while it’s not intuitive, it’s not impossible.

The first step is deciding how you want to define this new language. When considering how many grading scales to incorporate, it’s important to remember the overarching, ungrading goal of using feedback to reach collaboratively defined standards. Having a two-point scale (i.e. pass/fail) detracts from the necessary ‘redo’ element of ungrading and is in danger of reinforcing a fear of risk taking. Similarly, a five-point scale too closely mirrors the traditional grading scale for it to be effective. In this regard, the best-case scenario is to use either a three-point or four-point scale. A three-point scale allows educators to measure ‘meets’ or ‘does not meet’ standards, but also acknowledges and incorporates the learning process by providing a ‘resubmit’ option, while a four-point scale might also include a ‘not-yet-completed’ point to navigate the tricky settings of an LMS.

Our courses implement a three-point scale and student projects are evaluated as meets agreed upon standards, revise and resubmit, or not-yet-completed. Although we could include a fourth point of does not meet standards, we want our language to encourage resubmission, rather than just accepting that the project doesn’t meet standards. For those interested in eliminating zeros from the gradebook, but feel uncomfortable with the idea of giving students points when they have not submitted any work, this option allows for you to set the minimum grade at a number higher than zero, but students see a visual cue that clearly indicates that the work was not submitted.

How do I create a new grading language?

Although LMS platforms differ, we have found that these systems typically have very similar features. For example, while some LMS use the term schema to define the grading system, others use the term scheme – but they mean the same thing. Below we set forth the key elements to look for to hack your LMS for ungrading. Additionally, we have linked specific video tutorials for Blackboard and Canvas following the instructions, which are accurate as of 2023. Although LMS platforms frequently undergo updates that may alter some of the specific instructions, we have put together a series of landmarks to look for in your LMS that, regardless of the platform you use, should provide guidance in navigating your system, even if your platform settings aren’t exactly like ours.

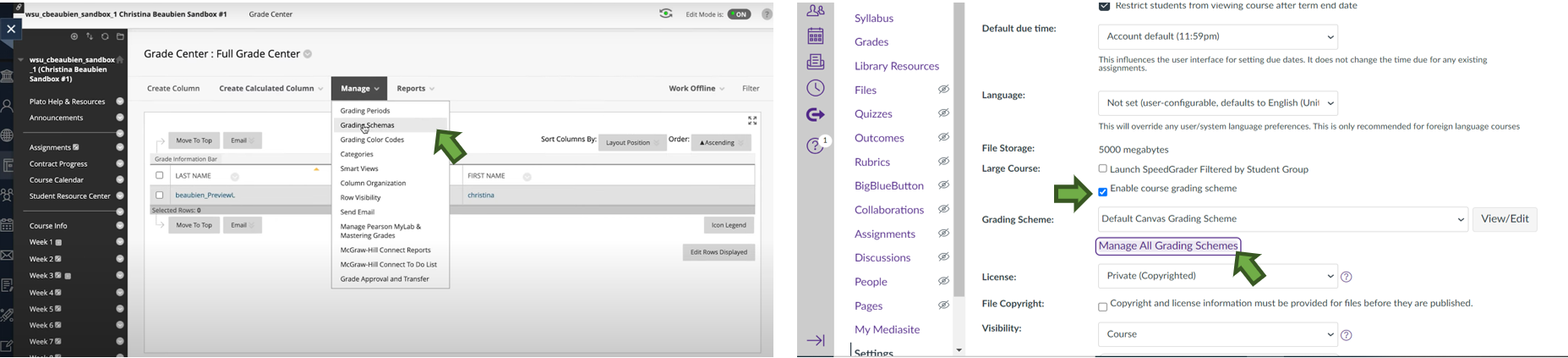

- Step 1. Find “Grading schemas” in your LMS settings

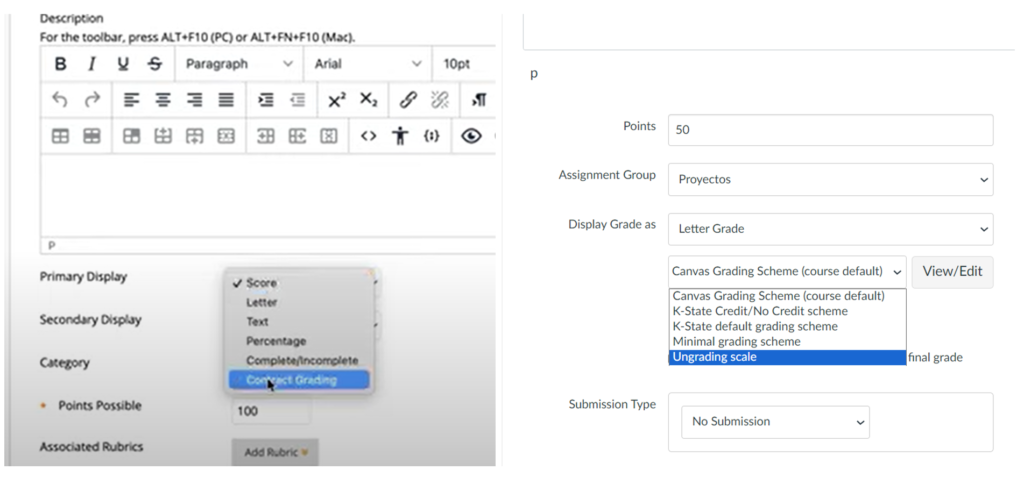

In your LMS course, navigate to your grade settings. In Blackboard, find “full grade center” then “manage” and select “see grading schemas”. In Canvas, click “settings” and scroll down to “grading scheme” under “course description” – ensure that the “enable course grading scheme” box is checked, then click “Manage all grading schemes”.

- Step 2. Create a new schema

For Blackboard, click “Create grading schema”; in Canvas, click on the button to “Add grading scheme” and give your new grading schema a title that will allow you to easily identify it later.

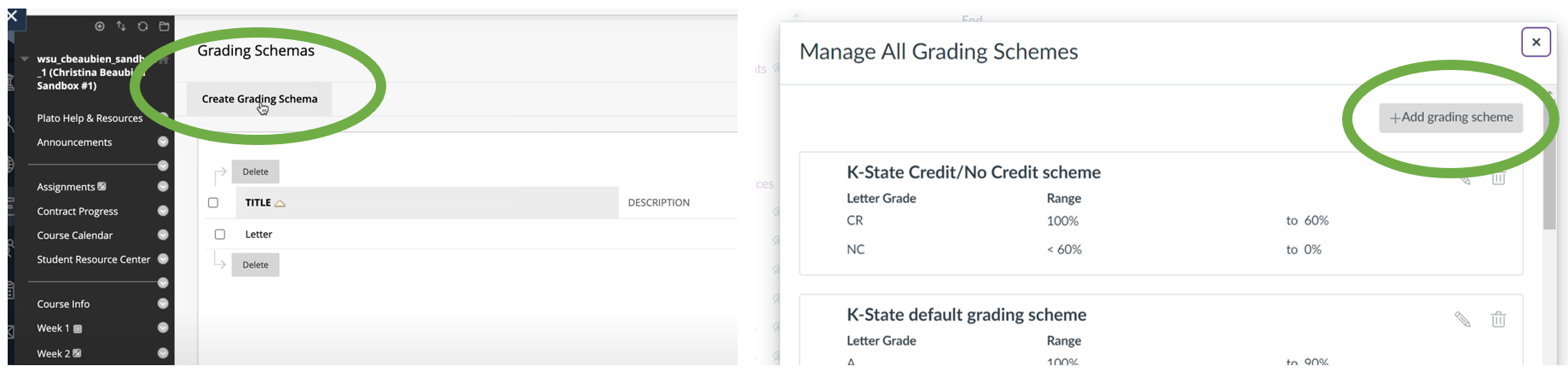

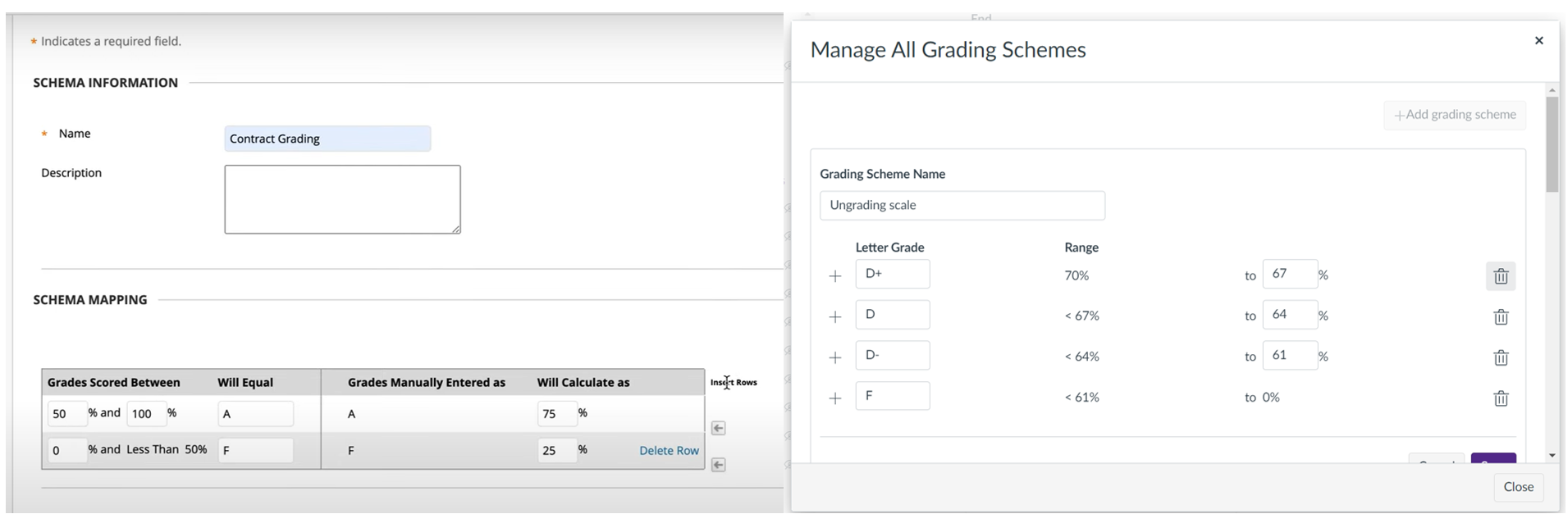

- Step 3. Design your new schema

Here is where you decide what you want your grading scale to look like based on your course assignments and evaluation needs. Consider how many evaluation options you want. As noted earlier, we like to keep the evaluation options simple and stick to three evaluation tiers. For Blackboard, you will click “insert row” if you want more than two options. In Canvas, you will click the garbage can icon next to the letter grade options until only the number of options you want are left.

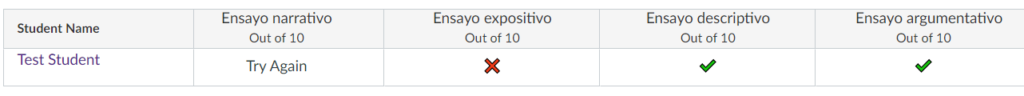

You will have to assign percentage ranges to your options that you will then use when evaluating work (whether or not you ultimately use them to calculate student grades), then select what you want the students to see if their percentage falls within that range. We decided to go with “✔”, “try again”, and “✘” as our options; these can be copied and pasted from other sources and, though we have not tried using fancy emojis, both Canvas and Blackboard display basic emojis and symbols without issue. The checkmark indicates that the assignment is completed and meets agreed-upon standards, “try again” indicates that the student submitted the assignment but it does not yet meet standards, they should review the feedback they received and revise and resubmit it, and the “✘” indicates that the assignment was not submitted.

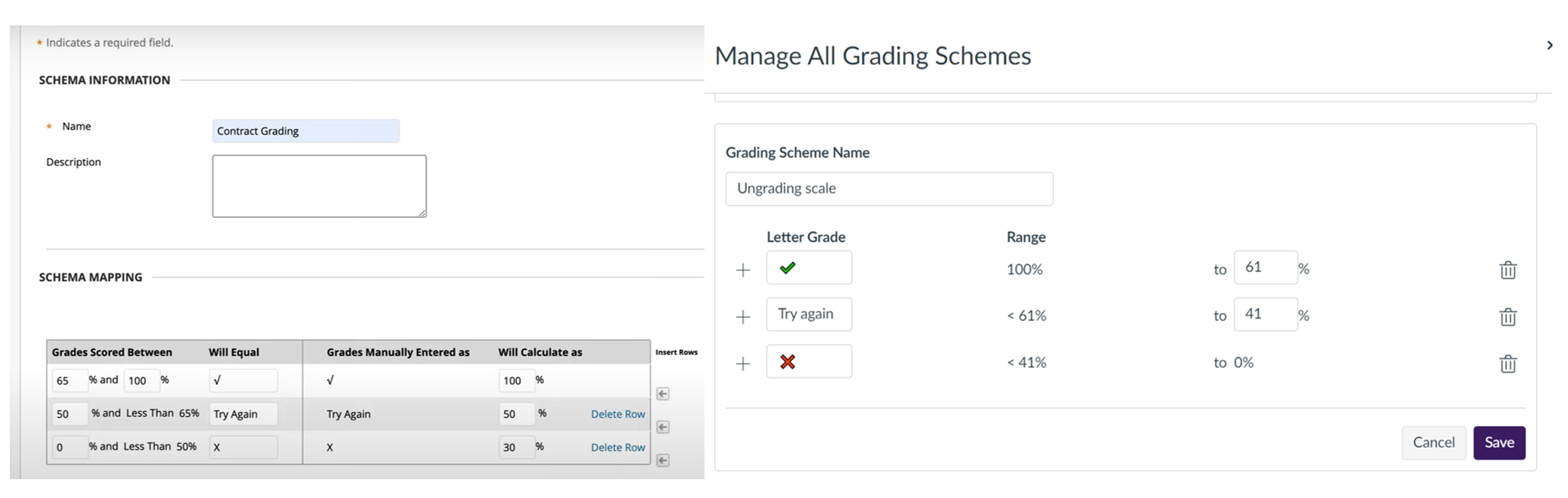

- Step 4. Apply the new grading schema to your assignment

Find the assignment in your LMS that you would like to apply your new grading schema to and select “edit”. Scroll down to the grading information (usually below the assignment description area) and locate the option for grade display. In Blackboard you will be searching for “Primary Display”; in Canvas you want the drop down menu under “Display grade as” – the default is usually to display grades as points or percentages. Select the drop down menu. In Blackboard, you will see your new grading schema as one of the display options to select. Canvas is a little trickier, you will have to select “Display grade as – Letter Grade” option, which will then open up a second drop-down menu where you can select your new grading schema. Repeat this step for each assignment you want to apply your schema to.

*NOTE: If you are using your LMS to calculate your final grades, it is imperative that you be consistent with the value for each tier of your grading schema. That is to say, the system requires that we input a range of percentage possibilities for each tier (e.g., “Meets standards” = 70-100%) meaning that the LMS will interpret any value between 70 and 100 as “✓” in the gradebook; however, for the system to be transparent and equitable, each instructor must assign each tier a single value. For example, we always input a 100 for “✓”, a 50 for ‘try again’ and a 30 for “✘”.

For more detailed information about how to use these alternate grading scales in Blackboard and Canvas, see the following video tutorials:

Blackboard

Canvas

The Final Countdown: Other Challenges Regarding Ungrading

Congrats! You’ve conquered your LMS! Although there will be other hurdles to consider when you decide to go against the grain, you can take comfort in knowing that your LMS won’t fail you (haha, get it?).

Other challenges that you might face include those that limit your curriculum and evaluative freedom, or even pushback from both high-achieving students that have been indoctrinated to confer worth from their grade as well as other educators who have been conditioned to stay in their comfort zone. For departments and school boards that limit flexibility, we recommend highlighting the established research against grading and their ineffectiveness to measure learning. We’ve included some suggested readings to help you build your justification arsenal. When dealing with high-achieving students that struggle with ungrading, you shouldn’t ignore their anxieties, but you can provide more clarity around the why and how for your choice of ungrading. One of the bulwarks of traditional grading practice is that it never explains itself – why are we choosing to use grades. In that vein, we like to include a why choose ungrading reading and discussion as a good jumping off point for most of our courses.

Perhaps the most important and salient piece of advice we can leave you with, now that we’ve fixed your LMS issue, is that we as educators need to constantly reexamine our choices regarding curriculum and assessment practice. However, we also need to check our daily language use surrounding the entire feedback process. Traditional grading has become so normalized that we often go against our own pedagogical instincts in order to uphold what has been ingrained, when the truth is that grades are an antiquated language for communicating progress. So although we can’t do much to change administrative and institutional realities that still cling to their traditional grading practice, we can create a new language inside our classroom that reshapes the way our students measure their progress. Most importantly, now you have the keys to make that change a reality within your Learning Management System.

Bibliography & Suggested Reading List

As we mentioned, when taking on an approach that goes against the status quo, there is often a fair amount of pushback. For that reason, we provide the following list of suggested readings, divided into categories based on topic.

Why is traditional grading practice inequitable?

Blum, S. D. (2017, November 13). Ungrading. Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/advice/2017/11/14/significant-learning-benefits-getting-rid-grades-essay

Brookhart, S. M., Guskey, T. R., Bowers, A. J., McMillan, J. H., Smith, J. K., Smith, L. F., Stevens, M. T., & Welsh, M. E. (2016). A Century of Grading Research: Meaning and Value in the Most Common Educational Measure. Review of educational research, 86(4), 803-848. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654316672069

Butler, R. (1987). Task-Involving and Ego-Involving Properties of Evaluation: Effects of Different Feedback Conditions on Motivational Perceptions, Interest, and Performance. Journal of educational psychology, 79(4), 474-482. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.79.4.474

Elbow, P. (1993). Ranking, evaluating, and liking: Sorting out three forms of judgment. College English, 55(2), 187-206.

Gardner, R. C. (2007). Motivation and Second Language Acquisition. PORTA LINGUARUM, 12.

hooks, bell. (1994). Teaching to transgress: Education as the practice of freedom. Routledge.

Kohn, A. (2011). The Case Against Grades. Counterpoints (New York, N.Y.), 451, 143-153.

Pink, D.H. (2011). Drive. Canongate Books.

Schinske, J., & Tanner, K. (2014). Teaching more by grading less (or differently). Life Sciences Education, 13(2), 159-166. doi.org/10.1187/cbe.CBE-14-03-0054

Stommel, J. (2017, October 26). Why I don’t grade. https://www.jessestommel.com/why-i-dont-grade/

How do I take small steps to reach my ungrading goals?

Blum, S. D. (Ed.). (2020). Ungrading: Why Rating Students Undermines Learning (1st edition). West Virginia University Press.

Elbow, P. (1997). Grading Student Writing: Making It Simpler, Fairer, Clearer. New directions for teaching and learning, 1997(69), 127-140. https://doi.org/10.1002/tl.6911

Nilson, L. B. (2015). Specifications grading: Restoring rigor, motivating students, and saving faculty time. Stylus Publishing.

Sackstein, S. (2015). Hacking assessment: 10 Ways To Go Gradeless in a Traditional Grades School. Times 10 Publications.

Stommel, J. (2021, June 11). Ungrading: An introduction. https://www.jessestommel.com/ungrading-an-introduction/

Stommel, J. (2023, April 17). Do We Need the Word “Ungrading”?. https://www.jessestommel.com/do-we-need-the-word-ungrading/

Stommel, J. (2023). Undoing the Grade: Why we grade and how to stop. PressBooks. https://pressbooks.pub/thegrade/?ref=jessestommel.com

Want a more long-term commitment to ungrading?

Feldman, J. (2019). Grading for equity: What it is, why it matters, and how it can transform schools and classrooms. Corwin.

Inoue, A. B. (2019). Labor-Based Grading Contracts: Building Equity and Inclusion in the Compassionate Writing Classroom, 2nd Edition. University Press of Colorado.

Much enjoyed this, thank you for all the useful suggestions. I certainly think prioritising feedback over grades is feasible for many of us teachers out there.