Students’ Perceptions of Sense of Virtual Community (SOVC) in HyFlex-Designed Spanish and German Language Courses

By Michael Dettinger, Nicolette Lopez, and José F. Rojas, Louisiana State University

Introduction

As universities returned to the 2020/2021 academic year, many were challenged with how to best prepare for course delivery. Some returned to face-to-face courses (F2F), while others maintained 100% online delivery, continuing what was started at the onset of the COVID pandemic. Other universities, including ours, chose to offer a flexible course delivery, the HyFlex design, which is considered to be courses that allow students to choose whether they participate in a course either 100% online or on-site (Ferrero, 2020) or that combines online and “on ground” teaching (Beatty, 2019). The HyFlex design helps to overcome many constraints in higher education, in particular delivering classes for students with conflicting schedules or travel difficulties. The design allows greater participation for all students that attend classes online or physically. In our case, we assigned students to specific groups to attend in person on alternate days and attend online via Zoom when not in person. However, they also had the option to take the class fully online.

While there is a growing body of research about technology-enhanced course delivery, there is a lack of literature on the implementation and effects of HyFlex models in higher education (Sowell, et al., 2019). Research that is available on this topic sheds some light for us in the results that emerged from our analysis; namely, how this learning environment helped establish a sense of community among our students. Blanchard’s (2007) comparative study measured the difference between the Sense of Community (SOC) in a F2F environment and the Sense of Virtual Community (SOVC). She acknowledged that the SOVC, in online contexts, and in SOC in F2F contexts sparks sentiments of membership, and a sense of belonging or identity which then allows better communication among students (Dawson 2006; Blanchard 2007). Moreover, as Blanchard (2007) and Chatterjee & Correia (2020) suggest, the sense of community will help establish a positive attitude in the course. Moreover, other research indicates that sense of community (SOC) itself can be considered as a good measure of learning (Chatterjee & Correia, 2020). We noticed these two important factors of learning/teaching and decided to inquire about how students felt about them. Therefore, our purpose is to provide an overview of students’ perceptions of Sense of Virtual Community (SOVC) in HyFlex design in undergraduate-level Spanish and German language courses during the Spring 2021 semester.

In-Class Activities and Technology Tools

Our goal for teaching via the HyFlex model was to mimic a 100% in-person learning environment as much as possible, where students in person and on Zoom had multiple means of communicating with the material and with one another, just as they might in an in-person setting. We felt this not only would help maintain a focus of learning the language content, but also to establish camaraderie and rapport among one another. As touched upon earlier, the students were divided daily into two groups with half attending in-person and the other half attending simultaneously via Zoom. We designated the students alphabetically and they were assigned to attend in-person two days a week and on Zoom for the other two days. Students were given the option to participate 100% online via Zoom, which was the case for several participants.All students who attended on Zoom were required to have their cameras on at all times and to treat their participation as if they were in an actual classroom.

As instructors, we all approached this design with the intent to involve students and manage the classroom as if it were a 100% in-person class. Students attending on Zoom, just as those in the classroom, were always welcome to participate voluntarily and were expected to do so when asked, just as if they were attending in-person. They were encouraged to either verbally ask or respond, and to use the Zoom features like “Chat” or “Raise hand” to post a question or response. If an activity involved a partner interview or small group activity, students in the classroom would break up into small groups, and students attending on Zoom would be designated to specific breakout rooms. We would then circulate from group to group to check progress or answer questions students might have had.

In-class activities included but were not limited to the following: lecture and modeling of grammar and language structure, topic overviews with examples and student application, reading exercises, listening to audio excerpts and video files, and cultural overviews. The cultural portion varied widely and included a number of examples, including interviews of native speakers, video tours of cities and geographic locations, and music videos and film excerpts. This was accomplished using various resources, but most included either the textbooks’ online components or other material from the internet, including but not limited to: culinary websites to highlight Vienna’s Kaffeehaus culture (www.cafelandtmann.at), YouTube videos such as Easy German and Spanish language music videos and film clips for language-specific examples, and glimpses into German- and Spanish-speaking cultures, as well as online newspapers and news outlets (www.spiegel.de, for instance) from German- or Spanish-speaking countries.

We also integrated a variety of technology tools and applications in the courses, including the textbooks’ online workbooks (grammar, video, and audio comprehension exercises), Moodle Forums (Blog) and Flipgrid recording exercises. In all courses the textbooks’ online workbooks gave students access to a variety of authentic audio and video, which helped broaden their understanding of culture as well as enhance their listening comprehension. In the German courses, students completed five blog exercises (one per chapter), in which they were required to answer an initial response, post an image related to their response, and respond to a minimum of two of their classmates’ posts. Students were also responsible for completing five recorded speaking exercises (one per chapter), using the web application Flipgrid. This typically followed a similar task assigned for the blog, so that the students had some familiarity with the topic. In some instances, the questions used in the Flipgrid exercise were the same as the blog task, but they also included different questions.

The goal of these online tasks was to have students apply their German written and speaking skills in an authentic scenario, and to interact with their classmates in order to create a sense of community. These types of activities (workbook audio and video, blogs and voice recordings) were then reviewed and discussed more in depth in class among students attending in person as well as on Zoom, allowing them to interact even more with one another, and reinforcing the content learned. This, we found, further added to the sense of community commonly found among each course.

Methods, Data Collection, and Results

Since our goal was to gain a better understanding of students’ perceptions learning Spanish and German via HyFlex, we surveyed them about their views on the effectiveness of this design and the technologies used as supportive tools to learn a second language and to improve their cultural awareness of the Spanish- and German-speaking worlds. The technologies we were specifically interested in were the course Learning Management System (LMS) Moodle, blog entries, and voice recordings. In the final weeks of the semester 89 students participated in a perception survey which included Likert-type and open-ended questions. Additionally, 12 students from both Spanish and German participated in a focus group interview to expand on their open-ended question responses. Our analysis of these data generated the following three themes that emerged from students’ responses: affective filter, language application (acquisition), and sense of community. Although these multiple themes emerged, the focus of this article was solely on the Sense of Community or Sense of Virtual Community.

Quantitative

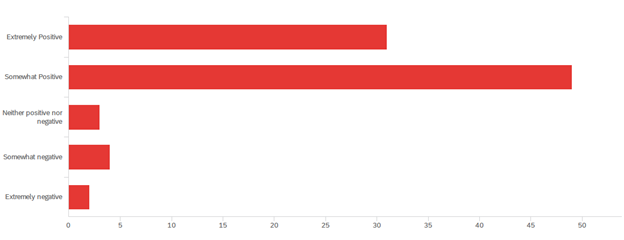

The quantitative results from the student perception survey indicated that students had an overall positive experience learning a foreign language in the HyFlex design. For example, we asked, “How would you rate your overall experience of taking a foreign language in a HyFlex environment?” (see Picture 1 on the following page). Among the 89 students who responded, 55.06% indicated that their experience was “Somewhat positive” along with 34.83% who indicated that their experience was “Extremely positive”. We found this feedback to be very encouraging. The positive response shows the language instructor that teaching in such an environment does not solely work as a means, but that it also works as a viable option for future course design options.

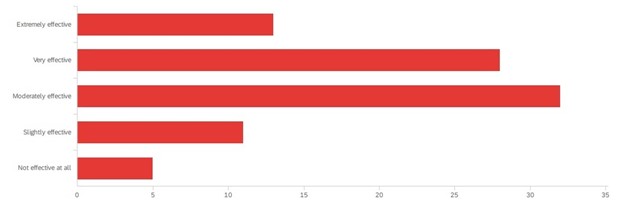

Another question asked, “Did learning in this environment (HyFlex) provide an effective means of enhancing your language skills?” Of the 89 students who responded, 84 ranged from extremely effective (14.6%), very effective (31.4%), moderately effective (35.9%), and slightly effective (12.3%). The remaining five (0.06%) indicated this environment was not effective in their learning. Picture 2 below illustrates the results to this question.

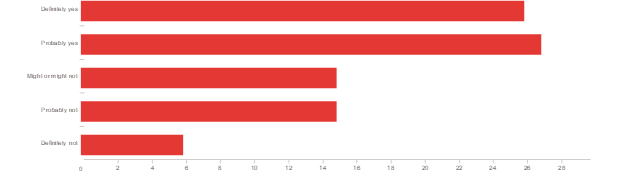

By observing these results, an overwhelming majority perceived this course design as an effective means to learn a foreign language. Lastly, from the question “Would you recommend this type of class for students studying foreign languages?” (See Picture 3 on the following page) we see that participants were inclined mostly to recommend it. These quantitative results show a pattern suggesting that the students were not only satisfied with the HyFlex format, but also they were very willing to recommend it. From a total of 89 participants about 27 (30%) answered “Probably yes.” Another significant portion of students (29%) answered the question “Definitely yes.” Also, some participants chose the answer to the question by checking the answer “Might or might not” (16.85%). Another group (16.85%) answered they were “Probably not” willing to recommend the HyFlex design. The last group of students (6.74%) answered a straightforward negative position in recommending this design responding, “Definitely not,” showing they were not satisfied enough to recommend it. Here, the majority of students recommended the HyFlex design, while, at the same time the question shows how satisfied they were with it.

Qualitative

The quantitative results gave us a good, overall impression on students’ views of learning in this mode. Their responses were reassuring to read; however, we wanted to also gauge if students felt a sense of community was established in these HyFlex courses. To accomplish this, we also asked them multiple open-ended questions, which provided a deeper understanding of how they perceived this learning environment. One theme that emerged from their responses, that was of particular interest to us, was the sense of community that was established in the HyFlex design.

We specifically asked: “Did you find there was a sense of community? How so? Was there a particular tool or interaction that was attributed to this? The students’ responses to this question varied but 67% (n = 59) answered positively. Here are several examples of their responses: One student pointed out: “There was a sense of community, everyone was there to learn German and progress. The blogs kinda helped with this sense of community.” Other students expressed: “This was because the instructor encouraged participation. Most of the time there were people willing to turn on their mics and answer the questions.”

Additionally, students added: “I do think there was a sense of community. I think my professor really made sure to have great communication with us. Dr. Rojas provided a positive environment for us. We also have a GroupMe where if we were stuck on something, someone was quick to explain something or just clarify something”. Also, “I do believe there was a sense of community within our class. I felt closest to my German class out of every class I have had at LSU so far. Everything from the Zoom meetings, in person meetings, and Moodle forums helped me feel closer with not only my classmates but the professor as well”. One student added “I think so! My instructor provided us with a lot of group work/breakout rooms that allowed us to interact with one another”.

There were some students who expressed they did not feel any sense of community, for example, “with the hybrid schedule, not all the students got to meet each other and the ones that did only saw one another half the time”. We feel it is important to include this, as it can help educators factor in multiple perspectives of students’ perceptions to help tailor the design of future HyFlex courses (or other) as optimally as possible. Additionally, participants indicated that specific in-class components (e.g. Zoom’s breakout rooms, Flipgrid, or F2F), contributed to a sense of community. Among a variety of answers collected, the researchers found that Zoom was the tool/app more often highlighted as a factor that triggered a sense of community, for example, when one student commented, “Zoom did really allow us to make those connections”.

Conclusion

Given the circumstances of teaching during a pandemic, our intent was to create as normal of a learning environment as possible to meet student needs. The results of our surveys indicated that students found this design to be positive, effective, and one that they would recommend to other students. Students also revealed that HyFlex design motivated them, allowed them to use authentic language applications, and helped create a sense of community. According to their responses, reasons that contributed to this included, but were not limited to: the course textbooks and online components, the role of the instructors and use of supplemental materials, and use of interactive technologies that allowed for authentic practice in the target language. We were quite pleased that students felt there was a sense of community established in this environment, especially during such an unusual time for many who would have preferred to attend class 100% in person or who held negative views towards online learning.

We also welcomed negative critique from students, as this was very helpful to us to read to learn on what could be improved. Even though the majority reacted positively to this design, it is important to also hear critique from students so that we as instructors can prepare differently or at least be aware of potential pitfalls with certain activities or delivery methods, online and/or in-person. While we felt that some of the negative responses may have been due to student apathy, for instance, “nothing about this style of class was helpful for me to learn”, some students gave very insightful criticism. For example, “the least helpful aspect of this course was the group discussions because I don’t think many people actually read anyone else’s posts to learn from them”.

Moreover, adapting to managing the HyFlex took a few weeks to adjust to, especially with finding the right balance of time when going back and forth between attending to the in-person group and the Zoom group. This included whether students were in small groups in the classroom and simultaneously in breakout rooms on Zoom as well as if there were no small group sessions. However, after a few weeks of getting to know the students and getting into the rhythm of the semester, this became easier to navigate and manage. Students became more familiar with one another as they typically would be in the same group when an activity called for small group work. This was the case for both in-person as well as for students in breakout sessions in Zoom. Because Zoom allows one to manually select who is designated in a particular room, we tended to place students in the same groups throughout the semester which helped continue their sense of community.

While there was a smaller percentage of students who revealed the HyFlex design was not conducive to learning, the overwhelming majority indicated it was an effective model for learning. As stated above, students’ responses indicated to us that use of interactive technologies, whether an authentic application from the textbook’s online component, asynchronous activities, such as blogs or voice recordings, or interactive/communication tools offered through Zoom (chat, poll, breakout rooms) helped create a sense of community and, more importantly, helped in their learning process. This is something educators should take into consideration when designing and planning future courses. Preparing for a HyFlex teaching approach allowed us to select the best means of both online and F2F teaching approaches, which can help in the creation of future online, HyFlex, and/or face-to-face-designed courses.

References

Beatty, B. J. (2019). Acknowledgements. In B. J. Beatty, Hybrid-Flexible Course Design: Implementing student-directed hybrid classes. EdTech Books. Retrieved from https://edtechbooks.org/hyflex/Acknowledge

Blanchard, A. L. (2007) Developing a Sense of Virtual Community Measure. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 10(6), 827-830.

Chatterjee, R., Correia, A. P. (2020) Online Students’ Attitudes Toward Collaborative Learning and Sense of Community. American Journal of Distance Education, 34(1), 63-68. http://doi.org10.1080/08923647.2020.1703479

Dawson, S. (2006). A study of the relationship between student communication interaction and sense of community. Internet High. Educ., 9, 153-162.

Ferrero, M. A. (2020) Hybrid and Flexible: A Professor’s Guide to Hyflex Teaching. Retrieved from https://mariangelf.com/a-professors-guide-to-hyflex-teaching/

Sowell, K., Saichaie, K., Bergman, J., & Applegate, E. (2019). High enrollment and Hyflex: The case for an alternative course model. Journal on Excellence in College Teaching, 30(2), 5-28.