The Russian Voices Project: Native-Speaker Interviews in the Foreign Language Classroom

By Irina Kogel, Five College Lecturer in Russian at Mount Holyoke College, the University of Massachusetts Amherst and Smith College.

By Irina Kogel, Five College Lecturer in Russian at Mount Holyoke College, the University of Massachusetts Amherst and Smith College.

DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.69732/QZPM2342

With the advent of video and messaging platforms such as Skype, intercultural collaborations between partner institutions in different countries have become increasingly popular in foreign language instruction. As ongoing scholarship attests, there is a range of different ways to use technology as a cultural “bridge” in the language classroom (Warschauer & Kern, 2000). However, since it is not always logistically possible to incorporate a full-length exchange into an already full curriculum, I have experimented with using recorded native-speaker interviews as a way to introduce a range of Russian speaker perspectives into the classroom. Not an exchange in the traditional sense, the Russian Voices project takes advantage of video to create one half of a conversation with which students can engage in their own time.

Extensive research has shown the effectiveness of video use in foreign language instruction and affirms that video, as a medium, is particularly well-suited to improving listening comprehension, developing communicative competence, and introducing cultural information (Heron et. al., 1995; Rifkin, 2003; Weyers, 1999). In beginning the Russian Voices project, I was motivated to supplement existing instructional videos for Russian to introduce more diverse perspectives, spontaneous language production, and a wider range of topics that could be used with students at different levels. The specific lacunae that a teacher of a different language may seek to fill will vary, but I believe that a project of this kind would work well across different languages.

Since the project began in 2014, I have conducted 15 interviews with 17 respondents: six men and eleven women between the ages of 19 and 70. Interviews were carried out in Moscow and St. Petersburg, and include individuals born in Astrakhan, Hauz-Han (Turkmenistan), Hong Kong, Moscow, Mtsensk, Samara, St. Petersburg, Ulan-Ude, Vladimir, and Yekaterinburg. The respondents include students, journalists, doctors, teachers, economists, and retirees.

In conceptualizing this project, I developed questions that could be grouped loosely by difficulty as they might be used in a three- or four-year sequence at the college level. For first-year students, the questions focus primarily on biography. At the second-year level, the focus is on hobbies and preferences. At the third- or fourth-year level there are open-ended questions about culture and abstract topics. Since each interviewee responded to the same set of questions, students can compare a range of answers on a given topic and begin to form a more heterogeneous view of Russia and the Russophone world. The interviews can be introduced from the first semester of Russian, and as students grow in their language knowledge, they can discover more and more about these individuals whom they have already “met” before.

Issues of Digital Accessibility and the Curb-Cut Effect

Working with recorded native-speaker interviews poses a number of logistical challenges, and one of these is making sure that our materials meet accessibility requirements. In this section, I want to make the argument in defense of what, from the outset, may feel like extra work.

For those unfamiliar with the term, the curb-cut effect posits that the “laws and programs designed to benefit vulnerable groups, such as the disabled or people of color, often end up benefiting all of society” (Blackwell, 2017). In the course of editing and making these interviews available to my students, I have found that complying with accessibility standards results in materials that can lead to better learning outcomes for all of our students.

As of 2010, current standards for digital accessibility are described in the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2. Two key accessibility components to consider include compatibility of the site and video player with screen readers and navigability without a mouse, and accessible multimedia content (which includes closed captioning to support hard of hearing students, and descriptions of what is on the screen for blind users).

When working with a web designer, implementing these standards is surprisingly straightforward on a technical level. We never know what students will walk into our classrooms, and it can make a huge difference down the line if the materials you create now are accessible. It is also possible to include advanced students in the frequently time-consuming transcription and captioning work that has to be done with materials that you have created yourself.

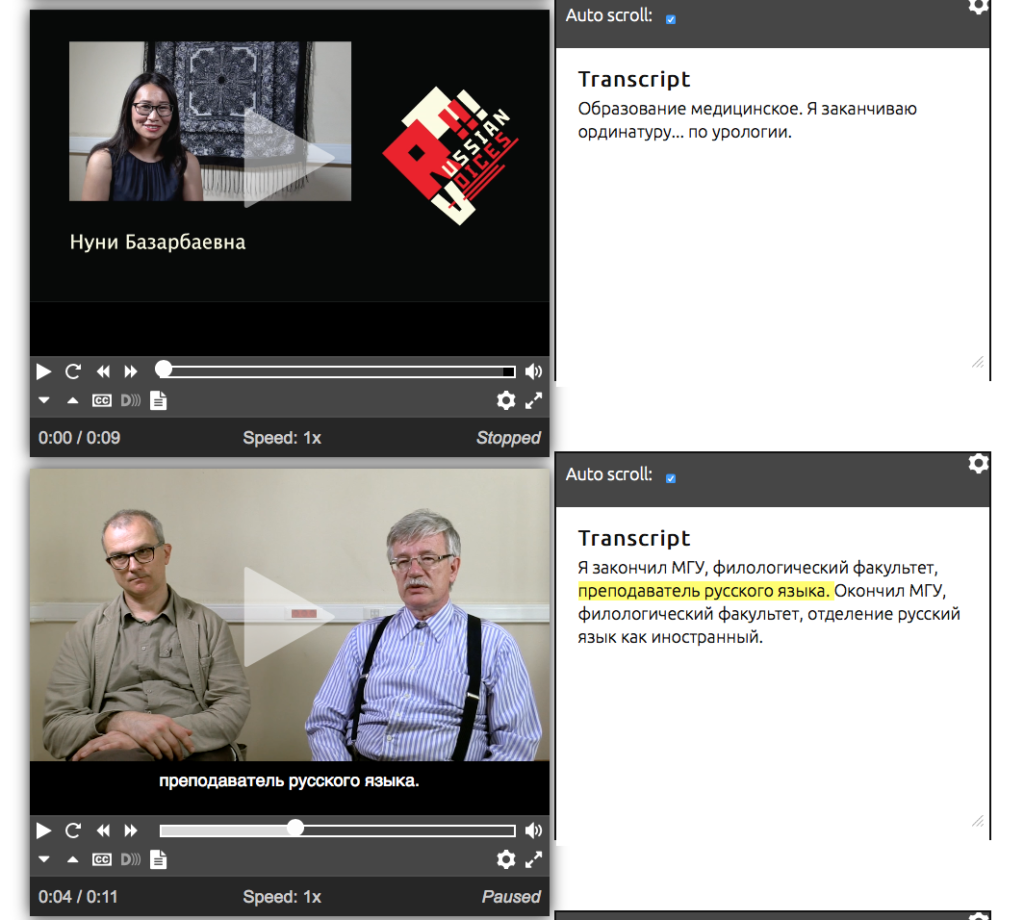

For my project, the main concern was finding an accessible video player plug-in. Working with the accessibility specialist on my campus, I decided to use the Able Player plug-in. Within Able Player, students can speed up and slow down audio, they can also turn on closed-captioning, image descriptions, and an auto-scroll transcript feature. As language teachers can easily imagine, a number of the accessibility features built into a system like this are especially useful for our language learners. With Able Player, all of the features can be turned on and off, and I have found it useful to play some videos in class without the closed captions and then have students watch the same videos at home and experiment with the affordances of the site. I have found that students are interested in testing their listening ability even with the aids available in Able Player. Knowing that the closed captioning and transcripts were available, gave my students the confidence to listen to the rapid native speaker speech. For those students who do not necessarily need all the affordances of Able Player for accessibility purposes, it is possible to test careful attention to the audio by asking questions about speaker tempo, pronunciation or recasts that are not noted in the transcripts or closed captioning.

Presenting the videos in Able Player gives students multiple ways of approaching the audio and visual material, and the support they need to feel confident encountering complex native speaker utterances.

In my students’ comments, I saw how the work that had gone into making the videos accessible helped to foster learning across the board:

- I loved the clips. The combination of audiovisual, transcripts and native speakers helps me so much. I can start to notice sounds and lip movements that I can’t get in the classroom.

- It was definitely easier to understand the clips the more I listened to them, and especially if I had the chance to read the transcript in-between “listenings.”

- I really like the audio-visual aspect and hearing from Russian native speakers. The visual aspect allowed me to see the person that was speaking and helped provide more of a connection to the definitions of happiness they provided.

The first response is from a student with hearing loss. Their response shows specific ways in which the site made the Russian content more accessible to them. The second response comes from a student who benefited from the site as a language learner, regardless of other issues of accessibility. Finally, the third response gets at the content and the connection they made to the speakers as a result of interacting with a video rather than purely audio content. In these responses we see the same accessibility affordances working to benefit students in different ways. In my experience, students’ engagement and motivation increased thanks to the features that were put into place to make the materials accessible, and I believe that the work we do now to comply with accessibility standards will serve all of our students.

Using the Interviews in the Classroom

On the whole, my interviewees’ responses were thoughtful and candid. The questions I asked elicited responses I could never have anticipated, including fond memories of a pet donkey in a straw hat, and regret over being forced to do math homework while the rest of the country was glued to the television watching Gagarin’s first flight into space. Interviewees shared stories of childhoods cut short by World War II and frankly discussed the role that religion played in their lives. For me, this diversity and spontaneity of answers is the chief advantage of working with native speaker interviews.

A number of paths might be charted by students through the Russian Voices interviews, and interviews like them. For example, as a final project in my first-year Russian course, students watch a handful of questions at the first-year and early second-year level and present on the interviewee they found most interesting. Later they use this format as a model for a video in which they tell a prospective host family about themselves. For second-year students, the Gagarin narrative provides an excellent resource for discussing a major cultural moment, as well as an authentic context in which to focus on verbs of motion. Third-year students use responses to the question “What role does religion play in your life?” in conjunction with a chapter on religious practice in Russia in the textbook Panorama to formulate their own answers to this question in Russian.

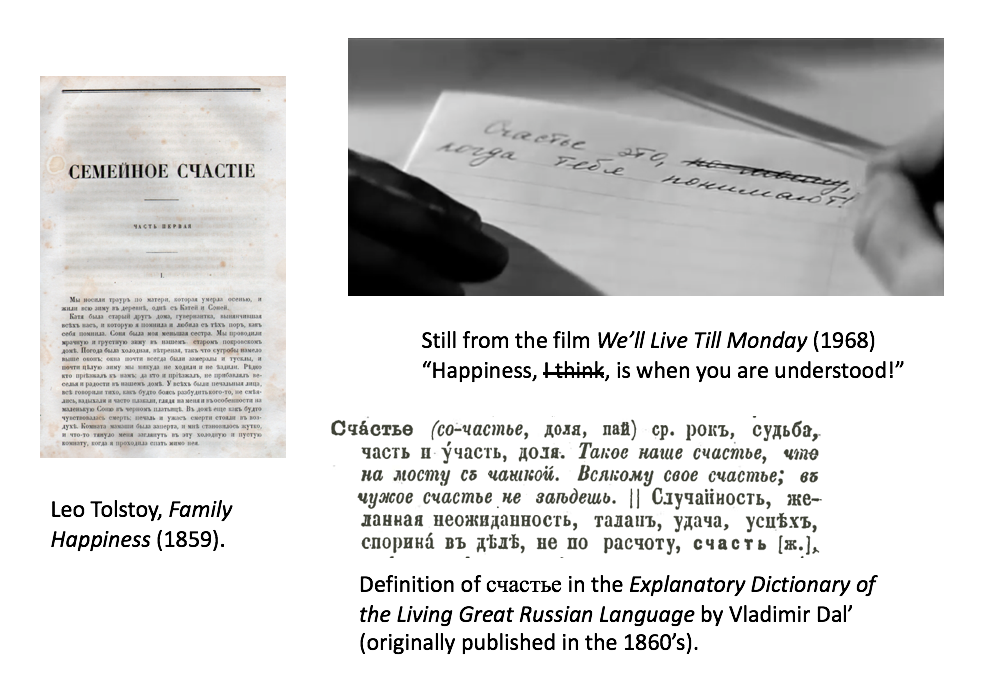

One lesson that has worked especially well focuses on how Russian speakers define happiness (счастье). This is a particularly Russian question, and students often expressed surprise “that some people were able to answer the question ‘what is happiness’ immediately.” In order to contextualize the individual responses, the interviews are used as part of a cluster of cultural materials including an excerpt from Tolstoy’s Family Happiness (1869), work with etymologies, and a clip from the 1968 film We’ll Live Till Monday, in which schoolchildren are assigned the task of writing an essay about happiness. In addition to mentioning family and love, some of my Russian respondents discuss happiness in terms of money and success, helping to break down assumptions that there is a clear dichotomy between Russian and American views of this concept. Some of the interviewees reference Eastern philosophies such as Buddhism and Confucianism, and one suggests outright that happiness is simply unattainable. My students responded to this cluster of interviews thoughtfully, and the discussions we were able to have in class afterwards were very productive. Below are some highlights from their post-class reflections:

- I learned that I have a very similar definition of счастье as native Russians. For me, it was very interesting to find out that even though my culture is very different from the Russian culture that my views aligned with theirs.

- I was surprised at how Russian happiness seemed to be derivative of external forms of teaching happiness. One woman referenced Confucius, while a younger man talked of how happiness is defined by Buddhism. Broadly speaking as well, all of their responses were in some way related to the theme written about by Tolstoy. It is as if happiness in Russia is a shared culture experience.

- I found that Russians can be surprisingly honest when talking about such personal topics. Also, the modern Russian conceptions of happiness is very different from what I grew up knowing about the meaning of “Russian happiness” (think: Soviet propaganda films with happy Soviets).

- We have these constructed views about what and how people think in different places in the world, when really those aren’t necessarily true or only true for a small percentage of people

What I have found working with these interviews, overall, is that students are eager to go beyond the information provided in their textbooks and hear more directly from Russian speakers. They watched the videos carefully and responded critically. Thanks to the affordances of Able Player, students were able to turn on the closed captioning and transcript features as needed and were generally very excited by how much native speaker language they could understand.

Native-Speaker Interviews in the Heritage Classroom

When using these kinds of interviews in a heritage course, it is possible to shift gears and to make the activities more personalized and more targeted to specific heritage speaker needs. For example, when we do the unit on «счастье», students call home after watching the videos to ask Russian speakers in their lives how they would define this term. These responses are then introduced alongside the interviews into the class discussion to allow students to reflect on how their friends and family are part of the larger Russian cultural sphere.

As a capstone project, students interview a Russian speaking friend or family member. The interviews contained in the Russian Voices project serve as a starting point for discussing the syntax of question formation and brainstorming what kinds of questions they might want to ask the people in their lives. Once students have constructed a list of questions, they conduct the interviews either in person during a break or over Skype. Students then share these interviews in class, which gives them a sense of being part of a heritage speaker community.

Another activity that I do with my heritage students is to give them a short clip from the interviews (without access to the usual affordances of the site) and ask them to produce captions for it. This exercise helps them to work on associating familiar words with the spelling conventions they have been learning in class. Research into both student-produced captions and the use of captioning to help improve delayed L1 literacy shows promising results, and might fruitfully be applied to the heritage context (see Kothari, Pandey & Chudgar 2004 for a discussion of the use of captioning in developing L1 literacy, and Williams & Thorne 2000 for a study that shows gains in language proficiency as a result of student-created captions). Though this kind of captioning work could be undertaken with a variety of video materials, the interview format is particularly useful because the videos largely lack background distractions and are focused, by design, on individual speaker utterances.

Conclusions

Introducing native-speaker interviews into the classroom has tremendous potential for helping to bring the languages we teach to life. While it is possible to use existing interview materials, the advantage of formulating your own questions and conducting the interviews yourself is at least two-fold. First, although the interviews are not scripted, since you have chosen the topics, it will be easier to weave the resulting interviews into an existing curriculum. Second, you can strive to include more diverse respondents among your interviewees.

Certainly this work also comes with some challenges. Since you are working with native speakers, there will be vocabulary and syntactic constructions that are unfamiliar to your students at all levels. However, since the topics take a theme being discussed in class as their starting point, students have an easier time associating what they hear with topics that are already familiar to them. This is also an excellent opportunity to discuss ambiguity and listening comprehension strategies. Another challenge is the time needed to conduct and edit the interviews, which is considerable. With a mind towards accessibility, we also have to factor in transcription and captioning time.

On the whole, however, given my students’ enthusiastic response to these materials, I feel that the advantages of including native-speaker interviews in the curriculum outweigh the challenges. The inclusion of such authentic materials helps to motivate our students and increase their cultural competence.

Thanks to a Five College Innovative Language Teaching Fellowship grant, a number of the interviews are currently available at russian-voices.org. Access to the materials is free, but in compliance with IRB regulations, an account is necessary to access the videos. In order to register, please follow instructions on the site to request a registration key and create an account. Feedback and suggestions are welcomed at admin@russian-voices.org.

References

Blackwell, Angela Glover (2017). The Curb-Cut Effect. Stanford Social Innovation Review. Retrieved from https://ssir.org/articles/entry/the_curb_cut_effect.

Heron et. al. (1999). The Effectiveness of a Video-Based Curriculum in Teaching Culture. The Modern Language Journal, 83.4, 518–533.

Kothari, B., A. Pandey & A. Chudgar (2004). Reading out of the ‘idiot box’: Same-language subtitling on television in India. Information Technologies and International Development, 1.3, 23–44.

Rifkin, B. (2003). Video in the Proficiency-based Advanced Conversation Class: An Example from the Russian Language Curriculum. Foreign Language Annals, 33, 63–70.

Warschauer, M. Ed. (1995). Virtual connections: Online activities and projects for networking language learners. Honolulu, HI: University of Hawai’i Second Language Teaching and Curriculum Center.

Warschauer M & R. Kern (2000). Network-based language teaching: Concepts and practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Weyers, Joseph R. (1999). The Effect of Authentic Video on Communicative Competence. The Modern Language Journal, 83.3, 339–349.

Williams, H. & D. Thorne (2000). The value of teletext subtitling as a medium for language learning. System, 28.2, 217–228.