Three Innovative Approaches to Integrating Emoji Into Your Language Lessons

Lillian Jones, Ph.D. student. University of California, Davis.

DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.69732/AFPR4213

Technologies will never cease to influence communication. If we look around our campuses, classrooms, and coffee shops we are sure to observe a generation deeply absorbed in their pocket pals, actively and willingly participating in some form of computer-mediated communication (CMC). There are many modes of CMC, such as email and video, but currently, the most favored one is messaging (Pew Internet, 2012). Here messaging refers to text messaging and messaging applications such as Whatsapp, Facebook Messenger, or WeChat. Hootsuite has reported these last three to be the top messaging apps of 2018, accounting for “nearly five billion monthly active users” collectively (p. 29). As a Spanish language instructor, my takeaway is that billions of potential second language (L2) learners are engaging in a highly social, real-world, authentic experience centered on language and communication.

However, we no longer text with just text. Enhancing the emotive function of these faceless interactions, are, well, faces (and objects). They wink, they frown, and they turn upside down; they grin, and think, and smirk their faces; they flex a bicep, they love letter, and they beach with umbrella; they are emoji. While emoji should not be considered a language by themselves, they do add to language, much in the same way that facial expressions, intonation, emotion, hand gestures, and objects help clarify what it is we are saying in real life. Internet linguist Gretchen McCulloch (2016) says “People aren’t using emoji as a substitute for language, they’re using it as an addition to it, just like you wouldn’t want to talk in person with your hands tied behind your back and a paper bag over your head”. So, emoji can add to language. My question is then, can emoji add to learning language?

As foreign language educators, don’t we endlessly endeavor to create authentic, social situations which provide opportunities for our students to practice language in real-world settings?

Therefore, in this article, I suggest three ways to integrate emoji into your language classes, focusing on vocabulary, culture and dialect, and digital storytelling.

Emoji and Vocabulary

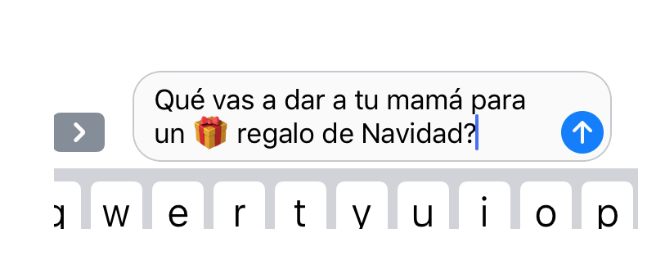

Li and Cummins (2019) showed results indicating that students using text messaging in L2 academic target vocabulary tasks learned significantly more target words than the group who did not receive the same treatment. Picture 1 is an example of how we might use emoji to present, practice, and review a thematic set of target language vocabulary centered around the theme of Christmas.

Vocabulary Presentation and Practice

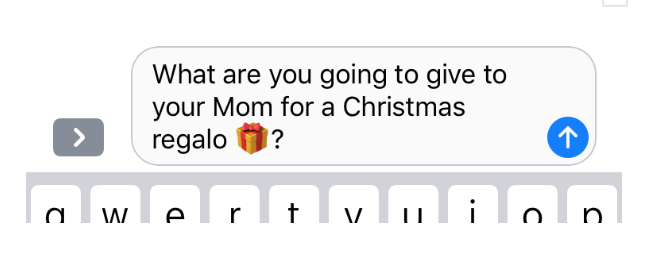

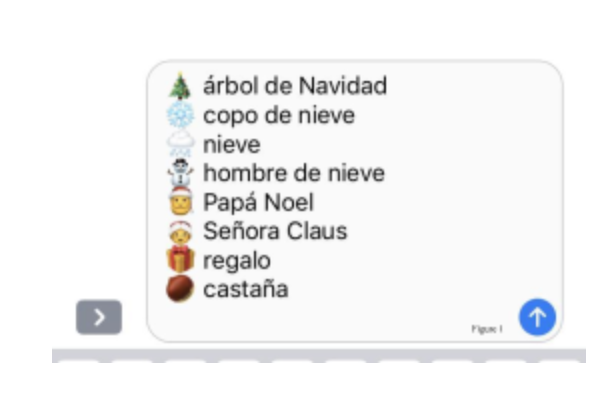

Present the target vocabulary by projecting the images from your cell phone using a live-cast platform or screenshots integrated into a PowerPoint. Because it is essential that learners receive both verbal and written information cues, an ideal setting would have the learners exposed to both aural and visual stimulation simultaneously (Schütze, 2017, p. 11). Thus, in addition to the new lexical items being displayed next to their corresponding emoji, the instructor should also read the word list and have the class repeat. Second, the vocabulary can be practiced by encouraging students to incorporate both representations of the word (emoji and written) into their actual text messages. Use of the target vocabulary may vary depending on language level. Examples are shown in Pictures 2 and 3.

|

|

|

Teachers may also find it effective to use simple L2 vocabulary exercises such as fill-in-the-blanks (Picture 4) or matching (Picture 5).

Fill in the blanks‘el ___________ () es verde.’, ‘el ____________(❄️) es frio.’ |

||

| Picture 4 – Fill in the blank activity for practicing new vocabulary | ||

| Matching – Draw a line that matches the emoji to its corresponding Spanish word.

copo de nieve ❄️ hombre de nieve Señora Claus ☃️ árbol de Navidad castaña Papá Noel nieve regalo |

||

| Picture 5 – Matching activity for practicing new vocabulary |

Vocabulary Practice

For practice, you can pair up L2 Spanish learners with each other or with a native speaker as texting buddies and prompt them to engage in texting discourse over the course of a semester. During these exchanges, if the emoji allow for a transparent meaning to replace an unfamiliar word, the learners would be advised to try and replace it accordingly, instead of stopping the flow of the conversation to look up the item. As well, one of the interlocutors may possess the lacking knowledge and respond back with the correct word, which would allow for the simultaneous occurrence of binding of the image and concept, negotiation of meaning, and negative feedback, all of which are integral parts of effective second language acquisition (Brandl, 2008).

Pictures 6 and 7 show micro conversations exemplifying this idea.

| S1: Cuando vas a estar en ? S2: en casa? S1: ah, si! olvido la palabra. Gracias! S2: A las 8. Nos vemos luego! |

S1: No voy a la fiesta porque los me dan miedo.

S2: Are those clowns? S1: Sí! No me gustan los clowns. S2: Ja ja *no me gustan los payasos. S1: Gracias, no me gustan los payasos. |

| Picture 6 – Example of turn taking via SMS involving a small communication breakdown. | Picture 7 – Example of turn taking via SMS involving a larger communication breakdown and repair. |

The communicative exchanges in Pictures 6 and 7 demonstrate not only a presence of multimedia input, but also brief communication breakdowns caused by the lack of linguistic information. When students experience these types of ruptures they begin to negotiate meaning, and through these misunderstandings and negotiation is when true learning can occur.

This principle also applies to the examples in Pictures 8 and 9. However, the specific highlight here is to encourage students to practice fluency by decreasing the number of times they stop and look up words, and to instead use emoji. This strategy is rooted in the SLA theory that in L2 reading we shouldn’t stop and hunt down every unfamiliar word we come across, but rather that we should try and sort out these words based on the context, since “When we skip unessential words, we read more, and acquire the meanings (or parts of the meanings) of other words” (Krashen, 1989, p. 458). Perhaps this same habit would also prove practical when employed to writing.

| A: k pasa? B: nada, estoy estudiando para mi examen de español. Qué haces? A: estoy comiendo . Es el cumpleaños de mi hermano. B: guau! Cuántos años cumple tu hermano? A: está cumpliendo 11. B: felicidades! |

A: cómo estás? B: + / – estoy cansada y A: tired and hangry? tienes hambre? B: ja ja, no. Estoy ….stressed out! A: ah, estresado! xq? B: tengo mucha tarea y también tengo que trabajar este fin de semana A: tal vez debes comenzar con una siesta B: sí, tienes razón. y tu, cómo estás? A: bien, estoy comprando nuevos para la boda de mi hermana. B: super divertido! A: hablamos luego! |

| Picture 8 – Text message exemplifying the use of a cake emoji instead of the unknown word ‘pastel’ in order to avoid stopping the conversation. | Picture 9 – Text message exemplifying negotiation of meaning, as well as the use of emoji instead of the unknown TL words in order to continue the conversation with fluidity. |

These types of basic vocabulary building exercises can be employed in class, assigned as homework, or carried out in casual text exchanges between students.

Vocabulary Review

Review the target vocabulary by playing lightly competitive games in pairs or individually, such as lighting rounds of ‘How many words can you get?’ in a timed session. You can put a list of vocabulary words on the board, and in a certain time, the team that lists out the most words via emoji on their mobile device wins (one device per group). Since the message will not be sent to anyone, but merely verified by the teacher, students can perform this activity in any function that allows them to access their emoji keyboard (e.g., a blank text message, other messaging apps, Google Doc, email draft, etc.) Students will insert the emoji, stop when the timer buzzes and the instructor will check each group’s list. This can also be done in reverse, with the emoji on the board and students respond with the word (either typed or handwritten). Variations of this activity will depend on variables such as class language level and activity objective.

Emoji and Culture: Dialects & Gesture

Intercultural competence is an essential component of language learning and concealed behind ,, and, and other emoji, are abundant opportunities to explore questions of culture, for example, dialect and gesture.

A dialect is a linguistic variety that depends on geographic, historic, and sociocultural factors; and these varieties can include differences in morphosyntax, phonology, and lexical items (Goetz, 2007). Understanding different dialects is an important component of learning an L2, one reason being that they are specific to certain regions and communities, thus contain a great deal of culture. Keeping this in mind, communicating within the emoji environment can potentially promote opportunities for cultural exchange, which may lead to the enhancement of the learner’s Intercultural Communicative Competence (ICC).

Discussing Dialects

The SwiftKey Emoji Report 2015 revealed the leading categories for all emoji use in a Spanish-speaking context: ‘Party’ for Spanish, ‘Baby’ for Latin American Spanish, and ‘Sad Faces’ and ‘Monkeys’ for US Spanish. The fact that this report outlines three distinct regional uses of emoji use in Spanish is an opportunity for students to learn about and discuss dialects, and delve further into how the various varieties of Spanish may have influenced these emoji groupings to be categorized as such.

Understanding Gesture Across Cultures

Furthermore, in a world full of waves, pointing fingers, and folded hands, it is important to remember that in addition to the differences in formal aspects of language (i.e. morphological differences like the ‘leísmo’ (Goetz, 2007) or lexical diversities, such as the many ways to say popcorn), gestures also differ in use and meaning across cultures. This same cultural awareness must also be employed when using gestures and symbols in emoji because the texter is essentially a gesturer; and as technology facilitates more opportunities where cross-cultural communication can occur, we must be sensitive to the cultural connotation of these mini faces, symbols, and gestures found in our mobile devices. Exploring this modern mode of nonverbal/non-written communication can provide fascinating cross-cultural insight, help us communicate effectively, and avoid embarrassing or even offensive mistakes. Take the folded hands for instance, . According to the 2018 BBC article “Why emoji mean different things in different cultures” (Rawlings) the representation of these two hands pressed together could potentially indicate a religious significance in the West or mean ‘please’ or ‘thank you’ in Japan.

In the classroom, a fun and compelling assignment is to appoint small groups and prompt them to select an emoji of gesture. First, the group will define the emoji in their native language, define and explain the emoji in the TL, and then explore its cultural significance within the target culture, including examples of its use in CMC. Because this lesson is meant to prioritize cultural content over grammar, the cultural significance portion can be carried out in the students’ native language. The instructor should encourage students to utilize a variety of resources to provide a comprehensive explanation of the emoji and its usage. Types of sources may include inquiring with native speakers, online research, and analyzing social media discourse. It is also important that the teacher reminds students that not everything found online is based on fact and students should select their information from credible sources.

Time can be allotted to work on the project during class and to close, students can present their findings to the class as a whole. The presentation should include the name of the emoji, a brief description, examples of its use in CMC (i.e., Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, text messaging, etc.), and a list of three things the students learned about its use in the target culture, as well as any additional unique cultural points that the students discovered and wish to share.

Emoji and Digital Storytelling

Humans are said to be inherent storytellers (Blake & Guillén, in press), and in today’s world, bite-size bits of storytelling via texting and social media are increasingly becoming ubiquitous in social interaction. In fact, social platform leaders, like Facebook and Instagram, have implemented a ‘stories’ feature, reflecting this innateness of humans to share that which is most important to them, their story. This is especially popular among young people and university students, the latter being our target group of foreign language learners.

Storytelling has long been an integral part of teaching language, both in L1 and L2. According to Castañeda (2013), digital storytelling is accepted by foreign language instructors as a valuable experience for students to participate in authentic activities and language learning tasks, meaningful to their own experience and learning goals. Additionally, if emoji are prominent enough to be nominated for word of the year (Ljubešić & Fišer, 2016, p. 82) and if they are being used by language learners as young as three to tell their stories (McCulloch, 2019), then perhaps there is a call to further investigate the use of emoji in digital storytelling for learning second languages.

Activity Using Scaffolding: Students Tell Their Stories

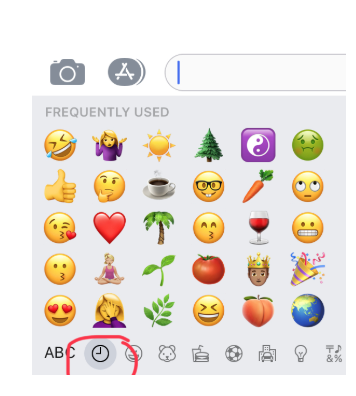

We can empower students to draw on what is important and relevant to them in their daily, hourly, and often live, communication, to tell their story in their second language, and ultimately, their second identity. The frequently used section of the emoji keyboard shows the 30 most frequently or recently used emoji. Here is one way to leverage this resource: students can work in pairs, small groups, or individually, and select just one row of the emoji or the entire set of the 30.

First, students select six emoji, three must be of an emotive nature and three must be an object. Students then define each emoji’s meaning in both their native and target language (TL), write a one-sentence description of how they use each one, and then write a short story utilizing all six. For example, from Picture 10 I would choose ☕️ and complete the following steps:

| 1. Define emoji in the native language, using emojipedia.org: – Rolling on the Floor Laughing ☕️ – Hot Beverage (coffee) – Face Blowing a Kiss – Globe Showing Asia-Australia – Thinking Face – Palm Tree |

2. Define emoji in the target language: – Rodando en el piso y riendo ☕️ – Una bebida caliente (café) – Una cara soplando un beso – Un mundo mostrando Asia-Australia – Una cara de pensar – Una palmera |

| 3. Provide a one-sentence description of how you use each one: – Rodando en el piso y riendo Uso este emoji cuando mis amigos y yo nos reímos de algo que es realmente divertido. ☕️ – Una bebida caliente (café) Siempre estoy sacando y subiendo fotos de mi café en Instagram. – Una cara soplando un beso Envío la cara que sopla besos a mi novio. – Un mundo mostrando Asia-Australia Cuando tengo ganas de viajar yo uso un mundo. – Una cara de pensar A veces uso esta cara para responder a mi mejor amiga cuando ella dice algo sospechoso. – Una palmera Utilizo la palmera para indicar que estoy en la playa y disfrutando el sol. |

|

Next, students individually take time to write a short story using the TL. For example,

El año pasado viajé a Tailandia . Allí hay muchas palmeras . Me encantan las palmeras. También, probé el café tailandés ☕️. Es muy rico y fuerte. La cultura tailandesa es muy única e interesante. Cuando intenté comer un insecto frito, hice una cara muy divertida y mí amigo se rió de mi . Todavía no estoy segura si me gusta comer los insectos.

Students then perform a peer-review and also receive feedback from the instructor. This activity can be completed in Gdocs. After the peer-review, students will share their docs with the instructor who will provide feedback, such as grammar or vocabulary depending on the lesson/task objective. The requirements, time, and production of this task may vary with the level of the learners.

For the presentation, the instructor will have all the short stories in one Google doc for ease and efficiency of presentation. Students will take turns coming up to the front of the class and telling (reading) their story. Classmates are encouraged to ask questions about the story, use of emoji, etc. The stories can be fictional or based on a true experience. Of course, they should be kept appropriate and relevant to the learning goals of the class.

Emoji & Storytelling: Additional Considerations

The following are just a few additional items to consider when implementing L2 storytelling practices of this nature. First, make it a group effort! Adding a collaborative component to digital storytelling can be an effective technique because these types of active methodologies can encourage the involvement of students in their own process of learning the target language and culture, (González-Lloret & Vinagre, 2018). Second, follow a framework! Utilizing a guide that includes the essential elements of storytelling, such as “an interesting beginning, problem, solution, and ending” (Stanley & Brett in Blake & Guillén (2020) 159-160), can keep the students on track, as well as maximize the pedagogical impact. Third, consider their comfort zone. Some research suggests that users feel safe and comfortable expressing more in their text messages than they might in other contexts (Wood, Kemp & Plester, 2013); and starting with a mode of communication with which students already feel comfortable could decrease student anxiety, enhance creativity, and increase expression in the L2.

Lastly, in a task-based learning situation, digital storytelling activities using emoji can be shaped using proper scaffolding, by starting off small on the individual level and moving into a larger project involving the entire class. Let us use the Christmas theme mentioned in the vocabulary building section as an example. The teacher will present the new information, such as vocabulary and cultural practices; and over the course of the unit, the teacher will create activities and facilitate situations for practice and review of the new concepts. Further, the students will work together (in small groups or pairs) to create a portion of a Christmas story using the new concepts. For example, one group may focus on food items specific to Christmas in Peru, while another group explores Peruvian Christmas Eve rituals, and another may target holiday decorations. After they work on their stories in small groups, the class will collaborate as a whole to put together an entire story of ‘Christmas in Peru’, building on their previous work. For the presentation of the comprehensive project, students should be encouraged to tell the stories using a multitude of multimedia, including emoji of course .

Put It All Together with Escondi2

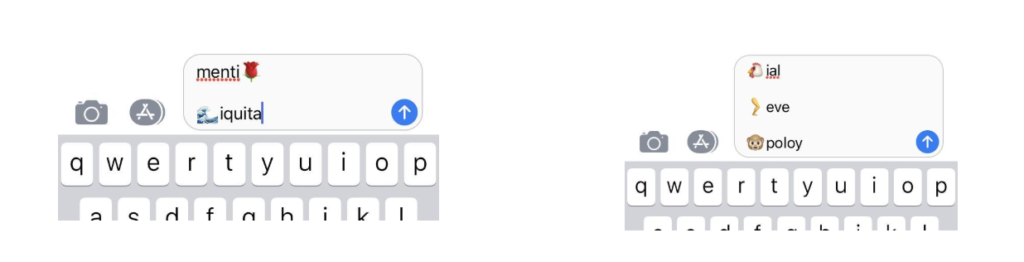

Play, practice, and review by combining all of the ideas discussed above in a game I call Escondi2. The foundation of this game is to provide students an opportunity to be creative with language, while they are learning, reviewing, or recycling vocabulary, as they find words within words, los escondidos (the hidden ones). The goal is twofold: to discover and review the individual emoji word, as well as discover and review the bigger word. Let us use the rose as an example. The word for rose in Spanish is rosa, and rosa can be found in words such as the noun mentirosa (liar, with a feminine subject).

There is the added bonus that using an emoji as the hidden word, also helps foster binding between the word and the image, as previously discussed. Depending on the level of the group, different Escondi2 activities can involve using either just TL vocabulary words (as shown in Picture 11) or a mix of both TL and the native language (NL) (as shown in Picture 12).

Try this exercise out by placing students in small groups and giving them time to come up with their own Escondi2. Students should be encouraged to use their book, their own knowledge, online resources such as wordreference.com, Linguee.com, and native speakers as resources. The instructor should move around the room offering support if needed. Once the time is up and all groups have created their Escondi2, they compete. The groups will go up in front of the class and present their word within a word in whatever way that is convenient for them (Google docs, mobile phone screen share, PowerPoint, etc.).

Escondi2 can be played in a variety of ways. For example, teams take turns presenting and the first team in the audience to guess correctly gets a point, and the team with the most points after all teams have presented wins. This game can also be adapted for a variety of time durations, such as a 30-minute activity or just five minutes at the end of class. You may also consider playing at the end of each week, publicly displaying the team points, and celebrating a monthly or end-of-semester winner.

For situations allowing more time, Escondi2 can be played using Kahoot! (www.kahoot.com). Each team creates their own round, including coming up with their uniquely developed Escondi2 term, as well as the three other possible (incorrect) answer choices. Each team will provide their information to the instructor who will put them into one master Kahoot!. Once the rounds are built out on the platform, the whole class plays, teams against teams. There will be one team that does not participate in each round, as they should not be guessing on the round which their Escondi2 is being displayed.

For effective play with Escondi2, it is suggested that the instructor has several Escondi2 terms or full phrases already prepared and stashed away should the moment arise when a quick game can be played. Additionally, in order to avoid repeating previously played Escondi2 terms, it is advised that during a game a list be visible so students know which ones have already been played.

Conclusion and Moving Forward

For these reasons and many more, I suggest that the use of emoji may offer compelling strategies for teaching vocabulary, introducing different aspects of culture and dialectology, and provides a unique platform where learners can tell stories. Emoji exist in a variety of genres including hand gestures, facial expressions, common objects, weather, places, animals, symbols, and so on; and language learners exist in a world of hand gestures, facial expressions, common objects, weather, places, animals, symbols, and so on. Accordingly, empirical studies and research-supported lesson planning and course design are the next steps in understanding the role that integrating emoji into the L2 learning experience may have. If the future of communication lies among messaging in our mobile devices, and if communication is a necessary component of language learning, then let us leverage these little faces and figures for foreign language teaching and learning.

I continue to think about ways to utilize emoji as a tool to enhance our L2 pedagogical practices. I would love to hear about your experience using emoji and ideas you have on using them to support second language learning and teaching. Please share in the comments.

References

Author unknown. (2012). Communication choices- Texting dominates teens’ general communication choices. Retrieved from https://www.pewinternet.org/2012/03/19/communication-choices/

Blake, R., & Guillén, G. (in press). Brave New Digital Classroom: Technology and Foreign Language Learning, 3rd Ed. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press. Unpublished book.

Brandl, K. (2008). Communicative language teaching in action: Putting principles to work. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson.

Castañeda, M. E. (2013). I am proud that I did it and it’s a piece of me: Digital storytelling in the foreign language classroom. Calico journal, 30(1), 44-62.

Goetz, R. (2007). La lengua espanola: Panorama sociohistórico. Jefferson: McFarland & Company.

Gonzaléz-Lloret, M., & Vinagre, M. (Eds.). (2018). Comunicación Mediada por Tecnologías: Aprendizaje y Enseñanza de la Lengua Extranjera. Bristol, CT and Sheffield, South Yorkshire, UK: Equinox Publishing Ltd.

Hootsuite Inc. (2019). Social Media Trends 2019. Vancouver, BC, Canada: Author unknown. Retrieved from https://hootsuite.com/resources/social-media-trends-report-2019

Krashen, S. (1989). We Acquire Vocabulary and Spelling by Reading: Additional Evidence for the Input Hypothesis. The Modern Language Journal, 73(4), 440-464. doi:10.2307/326879

Li, J., & Cummins, J. (2019). Effect of using texting on vocabulary instruction for English learners. Language Learning & Technology, 23(2), 43–64. https://doi.org/10125/44682

Ljubešić, N., & Fišer, D. (2016). A global analysis of emoji usage. In Proceedings of the

10th Web as Corpus Workshop (pp. 82-89).

McCulloch, G. (2019). Children are using emoji for digital-age language learning. Retrieved

from https://www.wired.com/story/children-emoji-language-learning/

___________. (2016). A Linguist Explains Emoji and What Language Death Actually Looks

Like. Retrieved from

http://the-toast.net/2016/06/29/a-linguist-explains-emoji-and-what-language-death-actually-looks-like/

Schütze, U. (2017). Language learning and the Brain- Lexical Processing in Second Language

Acquisition. Cambridge: University Printing House.

Wood, C., Kemp, N., & Plester, B. (2013). Text messaging and literacy-The evidence. Routledge.