Still Teaching Online? Unleash Creativity to Heighten Student Engagement and Build Community in the Asynchronous Language Classroom

By Heather Rice, The University of Texas at Austin

DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.69732/CCHU2850

Ask a teacher what it is they love most about their job and they’ll often tell you it’s the students. This is definitely true for me, and more specifically, it’s the community we build over the course of a semester or year together that makes any one class so special. In talking with my peers over the past year, something I heard over and over from seasoned and devoted language teachers, who were having to move their classes online for the first time, was a real concern about the potential loss of classroom community in the online setting. I knew exactly what they meant.

A few years ago I was asked to build an online introductory Russian language sequence for the Department of Slavic and Eurasian Studies at the University of Texas at Austin. At the time, online learning was gaining momentum but it was still a rather unpopular choice for instructors. Initially, I was among those unenthusiastic supporters of online learning. I had very little faith that teaching language online – mostly asynchronously – could actually work. I should state here that my job was not simply to put a pre-existing first-year language course online. I needed to create all of the instructional content as well. We would no longer be asking our students to purchase a textbook for this course, instead creating our own materials and teaching from them. I approached the task of creating online content with the resolve to make the online learning experience fun and engaging and to use the technology to suit our needs. I did not want to try to bend the online setting to perfectly mimic the face-to-face classroom. I wanted to find ways to exploit the medium to achieve our program’s goals.

Creating all new online language content is itself a beast. Creating content for online learning that will consistently engage and challenge students while also encouraging a sense of class community is a much larger beast. I was initially stumped on how to get students to buy in and engage as they might in a face-to-face class. Sometime during the pilot run of the online course, I realized that what often happened spontaneously in the face-to-face classroom was not naturally happening online in the mostly asynchronous class. Community, I understood, was something that must be integrated into the online curriculum. It must be intentionally built. I was not the first online instructor to realize this, of course. A quick search confirmed what I had experienced first-hand. I came across several articles, including one here, and blogs whose messages were aimed at the instructor’s need to intentionally cultivate community in the online class.

When we think about the notion of ‘community’, we tend to think of how students interact and engage with each other. This type of interaction is an incredibly important aspect of any communicative-based language class, and it is fairly easy to achieve online by designing activities that promote a high level of peer-to-peer interactivity. At this point, most language teachers who have taught online have learned that learning management systems, like Canvas, have certain tools, like ‘Discussion’ boards that make asynchronous video or text-based communication among students easy and visible to everyone in the class. There are many tools that can be exploited to the online class’s benefit and to help instructors find ways to encourage an online class community.

However, the notion ‘community’ is not limited to a group of people who interact with each other. It refers to a group of people who share something in common, whether it is a common goal, a particular identity, a geographical space, or some kind of experience. With this in mind, I wanted to pursue other avenues of interaction and engagement within my Russian course that would do just as much to promote community as do peer-to-peer activities. I resolved to get really creative with the course content and have fun with my role as the instructor for the sake of getting students to connect with the course as a whole and buy into Russian language and culture.

I would like to note that I came across the Community of Inquiry (CoI) in my research on ways to build community online. The CoI is a wonderful (and probably necessary) framework to work with when building an online class. The model describes three overlapping areas of ‘presence’ that must be activated in an online curriculum in order to achieve optimal learning outcomes. Although this model for online learning is exactly the kind of thing instructors need to consult when building any online course, I was interested in the notion of ‘community’ as defined as a kind of shared experience by a particular group of people, and I wanted to find ways to increase student interaction and engagement in order to build a supportive and vibrant classroom community online.

I wondered if I could encourage a greater degree of student engagement online through my endeavors as the instructor and through the course content itself. In what follows, I describe how I have tried to heighten student engagement and foster a sense of community online with creative uses of the technology available to me.

“Будем на связи” – Online Russian at the University of Texas at Austin

One of the greatest pieces of advice I was given upon embarking on this endeavor to create this online course was to make the classes FUN. Additionally, Dr. Thomas Garza suggested we might name the course ‘Будем на связи’, which is a play on words in Russian. It means both “We’ll be in touch” and “We’ll be online.” I could not have asked for a better title for this project. The first thing students see when they log into the Canvas course site is a fun and whimsical cartoon drawing of myself and my first TA. In the image we are seen talking to a hedgehog I named Oleg. I’ll get to him and why I chose that particular name in a minute.

As I stated before, all of the instructional content for the online Russian courses is new material. Since we use Canvas as our learning management system (LMS) at UT, I was able to build the bulk of the course and all instructional content directly into it. In doing so, I tried to mimic the structure and layout of a typical textbook in order to make the presentation of materials familiar and somewhat predictable to students. There is no printed textbook for my class, but the materials are all arranged in textbook-like format. Content is divided into thematic chapters, which are all introduced with a stated list of communicative and cultural proficiency goals, and topics are sequenced in line with other well-known and widely-used Russian textbooks.

On one of the first Canvas pages students see, I introduce myself and any teaching assistants who may be working with us in any given semester. The following is a screenshot of my “Будем на связи” avatar and one of the first TAs for the online courses, which I include on this introductory page to pique students’ interest and begin to bring them into the world of “Будем на связи”. Even though Molly is no longer an active TA, students see quite a lot of her. She appears in so many of the course’s videos and drawings that she deserves an introduction.

I try to make my presence known from the very beginning and I like to maintain a strong instructor presence throughout the duration of any given semester. I have found various ways to do this, which can arguably be labeled as fun. I often quite literally insert myself into both instructional material and into student assignments. A lot of the instructional content consists of videos of me either in front of a green screen or a light board, explaining or demonstrating some aspect of Russian language or culture. Luckily, while creating the content for this course, I had access to a fully outfitted video recording studio as well as a talented graphic design team who helped me execute high quality content.

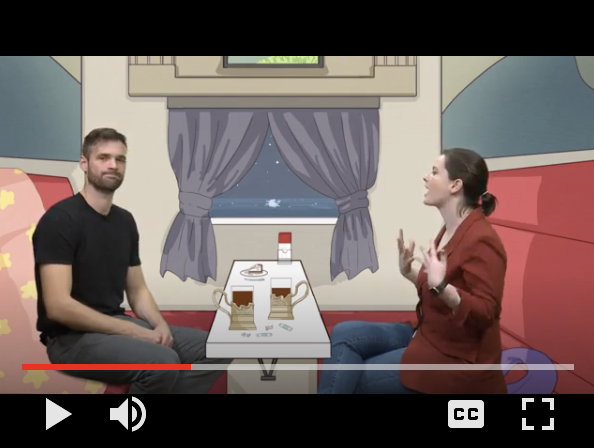

In the image below, my former TA, Molly, and I talk to each other about what we are reading, demonstrating one use of the Accusative case in Russian.

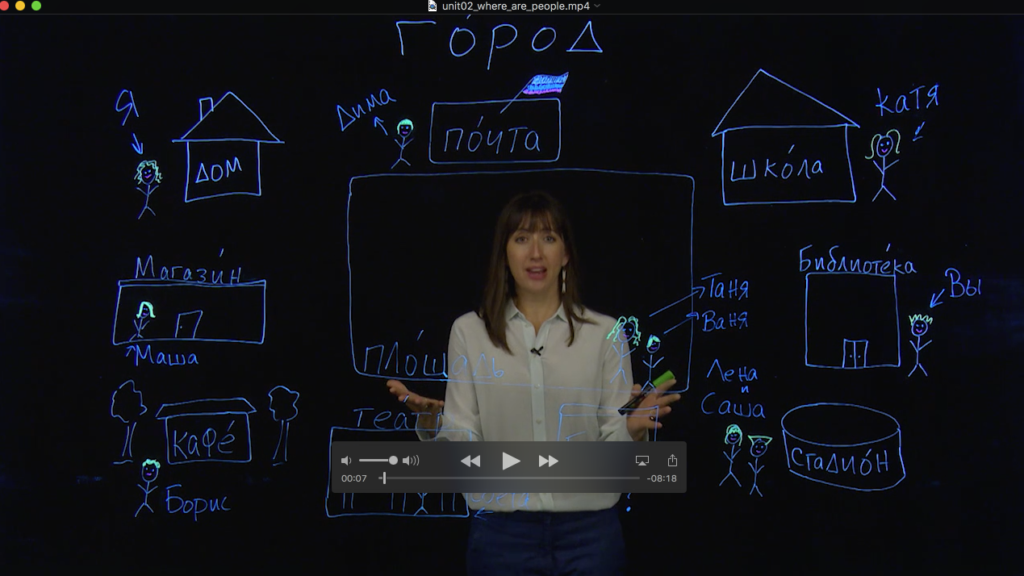

In the next photo, I am at a light board, or learning-glass screen, talking to students about places in a generic city. I created this very basic visual to model how to talk about places we may visit. Rather than stand at a whiteboard with my back potentially to the class, I stand behind this clear screen and, with the magic of technology, I am able to write as I normally would. The image is flipped in post production so the viewers can read what I write or draw, although I do appear to be left-handed, which I am not. I use the light board to do what I might do at a whiteboard in a classroom, whether it is drawing images, like the one below, or conjugating verbs. In the spirit of making myself as visible as possible and engaging the students, I simply do what I might do in class at times. I talk to them about some of the sticky, non-intuitive aspects of grammar. I am everywhere and I encourage whimsy at every turn.

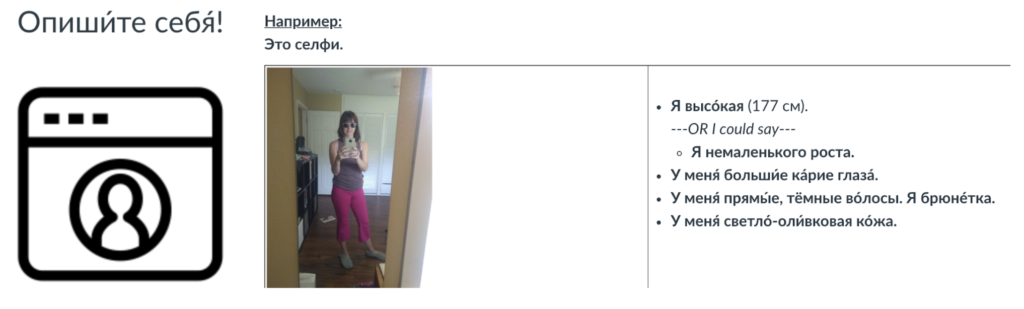

The green screen and light board videos I have been fortunate enough to make are wonderful and I am so grateful to have had this technology at my disposal. These are not necessary, however, for creating a highly interactive course, in which the instructor is visible to the students. I have often forgone highly produced videos in favor of simple desk or phone recordings for use in student assignments. This is something any instructor can do and it is all in an effort to stay constantly in the students’ line of sight. In a world of selfies and TikTok, low-budget and informal videos are something students can readily identify with. In the image below, I have shared a selfie with my students on a Canvas Discussion assignment. The assignment asks students to describe their physical appearance. They are invited to share an image of their actual or unreal selves (students never have to share anything they are uncomfortable with).

I also make it a point to engage with my students on their assignment submissions. Canvas allows the instructor to leave voice, video, and / or written feedback, so I make use of this as much as I can in the way that makes the most sense for any given assignment. I may leave video or voice feedback when I want to demonstrate proper pronunciation. I may leave written feedback that doesn’t involve commenting on students’ use of Russian but on what they tell me. I try to engage students through assignments themselves. In this way I give them the chance to share various aspects of their lives, to the extent they are comfortable with it. For example, in one assignment, a student told me what she likes to do in her free time, which is to bake cookies and play with her dogs. In the comments, I asked about her dogs, because I also have a dog, and she later responded to me. Our conversation involved some Russian but, more importantly, it allowed me the opportunity to engage the student in a conversation about her and her interests.

I set the tone for student engagement very early on in class. I want students to feel safe and respected and also to understand they are expected to behave respectfully and appropriately in class with both me and their classmates. In the image below, I am quite literally modeling ridiculous clothing combinations to teach language for talking about getting dressed. I mean to grab students’ attention. I want to elicit a reaction. I want them to be entertained. I want them to want to respond.

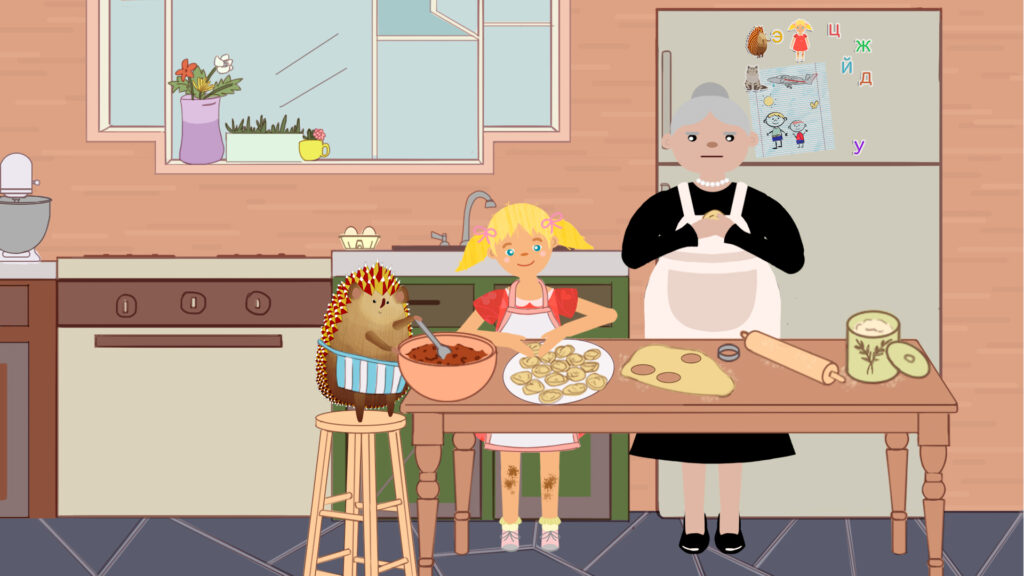

The course materials, in addition to being organized and structured according to modern pedagogical principles, need themselves to be engaging. They need to be especially engaging for the online audience. For my online Russian classes, I opted to include an overarching narrative, as well as include some recurring themes and characters throughout. Since forest animals are beloved creatures in Russian culture, I chose a hedgehog (who I named Oleg) to be our Russian-learning protagonist. As Oleg learns Russian alongside our students, he befriends a Russian girl and her family. Over the course of three semesters my students get to know Oleg and his friends very well, mostly through short readings and images woven throughout their assignments. Oleg experiences many aspects of Russian culture: he hunts for mushrooms, travels on an overnight train to St. Petersburg to see the White Nights, goes to tea, visits a banya, learns to make pelmeni, watches a famous cartoon about a hedgehog, as well as many other things.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Students see Oleg a lot – he is part of their shared online Russian experience and he is unique to the online Russian classes at UT. The students share this experience of getting to know this character who was created just for them and he becomes emblematic of their online learning community in a way. He is called Oleg [alj’ek] because this name happens to contain all of the major phonological features of Russian: vowel reduction of the initial /o/, secondary palatalization of the /l/, and word-final devoicing of the /g/. I wrote my dissertation on Russian phonology, so I am particularly proud of this. If students can successfully say his name by the end of the first semester, they’ve accomplished something.

Just as I have made efforts to engage students directly in my role as the instructor, I have tried to find creative ways for students to engage in Oleg’s world. For example, one assignment asks students to write a birthday card to him. What tends to delight students is that he replies to them.

At other times, again with the magic of technology, I have inserted myself into Oleg’s world, allowing for a virtual crossover between myself as the instructor, the materials, and the students. I am able to reach out to the students through the central story. In the video still below, Molly and I play a game of Guess Who?, describing the characters in Oleg’s world. After watching, students have a similar task. Using language they have been learning, they describe the characters they see on the screen.

I imagine that putting myself into Oleg’s two-dimensional world is unexpected for the students. It grabs their attention and, hopefully, excites them and encourages greater engagement with these materials. In the image below, Molly stands at Oleg’s refrigerator, telling me off-camera what food there is. To the right Oleg is pictured in this same kitchen learning to make Russian pelmeni.

|

|

|

Finally, in the examples below Oleg and his friend Polina are taking an overnight train to St. Petersburg. Students read about their trip in one assignment and then learn about acceptable travel behavior in a separate discussion by watching a short video in which Molly and a friend are two Americans traveling on this same train. Again, this crossover between the instructors and the Oleg storyline is done intentionally to heighten student engagement in the online course. The whimsy adds a much-needed lightness to what is often perceived as the very difficult task of learning Russian.

For anyone still reading this who might be thinking I could only do these things because I was lucky enough to have access to a video production studio and talented graphic designers, I would say this is partly true, but I only made the decision to insert myself into Oleg’s two-dimensional world later on in the development process and after piloting the course. The Oleg storyline is a big part of the online Russian content. The graphics were created to complement readings about his adventures. In the hopes of further grabbing students’ attention, I decided to open the storyline up and allow for instructor crossover into the imagined world of Oleg. I got creative with the materials I had. This crossover added an exciting dimension to the original reading materials and, hopefully, made them more interesting in the context of the course. I made myself a sort of conduit to this make-believe world and brought the students a little closer to it. If you are someone who is tasked with creating an online course with existing or open materials you have not yourself created, you can still find ways to creatively engage your students with them.

|

|

|

In this article, I share how I have utilized my role as the instructor to try and foster a sense of community in the online classroom. It has been my intention to encourage a high level of student engagement and interaction by creating opportunities for shared, often whimsical, experiences that are unique to my online class. In providing various avenues for engagement and reaching out to the students through creative means, I have witnessed actual community development in my online classes.