Contextualizing Language Learning Using TAGs

|

Maria Alley, Senior Lecturer in Foreign Languages, University of Pennsylvania, Pennsylvania

|

Molly Peeney, Lecturer in Foreign Languages, University of Pennsylvania, Pennsylvania |

DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.69732/OVPI3233

Authenticity of language, language tasks, and assessment have been key principles of language teaching and learning in recent years. We, as teachers and developers of our curriculum, always look for effective ways to contextualize language learning and to engage our students in real-life situations and tasks. In this article, we will share our experience in developing and implementing a series of activities based on so-called “TAG” videos in our elementary and intermediate Russian language and culture courses at the University of Pennsylvania because we have found them to be a great fit for our purposes.

WHY TAGS?

“TAGs” are individual questions or sets of thematically grouped questions that video-bloggers use to, well, tag their posts. Examples of TAGs include:

- “What is in my (school) bag?”

- “What is on my phone?”

- “What am I reading?”

- “If I were…”

- “What presents did I get for New Year’s?”

TAGs help to identify bloggers’ and viewers’ interests, to make those interests easily searchable online, and to include participants in an enormous online TAG community. We are not sure of the popularity of TAGs or similar phenomena in other languages, but TAGs are a salient part of the Russian-speaking online culture and seem to enjoy the most popularity with pre-teens and teens, especially young women, although we generally don’t have any problem finding TAGs by a variety of speakers. The appeal of TAGs is similar to the appeal of viral challenges, such as the ice bucket challenge. The TAGs you will find on Russian-speaking YouTube vary widely with respect to their country of origin, their blogger profiles, and their popularity — some TAGs have only a few views and others have millions of views. TAG culture is robust and includes its own counter-culture of funny parody videos. Overall, TAGs offer students of Russian rich opportunities to actively and meaningfully engage with this part of Russian-speaking cultures in a way they might in real life.

WHICH TAGS DO WE USE?

In our program, we currently use TAGs at two points in the curriculum, in the first and in the fourth semester. In first-semester Russian, the third unit centers around personal possessions; the popular TAG question “Что в моём школьном рюкзаке?” / “What is in my (school) bag?” serves as the unifying “text” and basis for assessment for the unit. In fourth-semester Russian, a cluster of TAG-based activities complement the last unit on weather conditions and clothing and is used as part of formative assessment in the unit. The fourth-semester TAG, called “Если бы я…” / “If I were…,” requires command of the subjunctive mood, relating to conditional situations, in order to be able to respond to hypothetical questions such as, “If I were a film director, what kind of films would I make?” and “If I were a dog, whom would I bite?”.

Video 1. Example of an authentic “What is in my bag?” TAG

Video 2. Example of an authentic “What is in my bag?” TAG parody:

Video 3. Example of an authentic “If I were …” TAG. This TAG includes a list of 15 hypothetical questions that all video bloggers answer in the same order.

HOW DO WE USE TAGS IN CLASS?

In both TAG clusters, we begin our work in the interpretive mode of communication, when our students watch, analyze, and respond to authentic TAGs in class. In elementary Russian, we begin watching TAGs “What is in my bag?” early in the unit, once the basic vocabulary for personal possessions has been introduced. TAGs serve as a great tool for working on listening comprehension, they offer rich material for cultural analysis and serve as a model for personalizing vocabulary related to possessions. While everyone might have keys or headphones in their bag, not everyone will have a flute, a tea bag, or a book holder. Students usually watch two different TAGs in class, both chosen by the instructor, and are encouraged to find and watch relevant TAG videos on their own at home before making their TAG video.

In-class activities tend to focus on listening and speaking, and at-home activities on listening and writing. At both levels of instruction, we do our best to conduct all in-class activities on viewing and discussing TAGs in Russian, while homework activities generally use a mixture of Russian and English, especially when we deal with grammar explanations, translation tasks, and more abstract questions that go beyond students’ current level of Russian. When we begin working with TAGs in elementary Russian, students have about 35 hours of Russian and, as you would expect, are quite limited in what they can express in the target language. Nonetheless, in-class discussions are done almost entirely in Russian and are followed by a 7-10 minute “debriefing” session in English, to allow for a more nuanced analysis of the videos.

In this analysis, the aim is to obviate the process of watching, reacting, analyzing and forming an opinion about YouTube videos that students do automatically in their first language, almost unconsciously. We focus on how a TAG reflects the personality of each individual blogger (his or her age, gender, personality traits) and the blogger’s cultural context (the year it was recorded, country of residence, etc.) and we prompt the students with a series of discrete, manageable questions, such as:

- What are the markers of the “genre” of TAG videos?

- What greeting is used?

- Is the register formal or informal and why?

- Is the greeting different than what we would expect in a face-to-face context?

- What unspoken elements of the video (gestures, facial expressions, other visual cues, props, etc.) contribute to the communicative content of the video?

- How do the bloggers end their videos? Why?

- What is common to the various answers to one TAG?

- What practices, beliefs, opinions are common and why?

- Would we expect similar answers from Americans, people from other cultures? Why?

We also consider parody videos because they offer additional fascinating insights and because students really enjoy watching them. Some questions we consider about parodies are:

- What becomes the focus of parody and why?

- Why are specific references, visual clues, and gestures funny in a particular context?

Lastly, we ask students if they would “like” the TAG and what comment they might leave for the blogger.

In this first phase of watching and analyzing TAGs, students gain confidence in working with and understanding authentic Russian videos recorded by a variety of speakers and increase their active vocabulary relating to the current thematic unit, as well as the language of online communication. Most importantly, however, students do something that they probably do in real life: watch YouTube videos.

HOW DO STUDENTS USE TAGS AT HOME?

TAGs lend themselves to a variety of approaches to working with form and to varying levels of form-focused nuanced support. While the at-home component in the elementary class is less structured, in the intermediate class, we scaffold three different TAG-related homework assignments before students make their own TAGs. In the intervening class days, we incorporate TAGs less formally by watching a new on-topic TAG as a warm-up, for example.

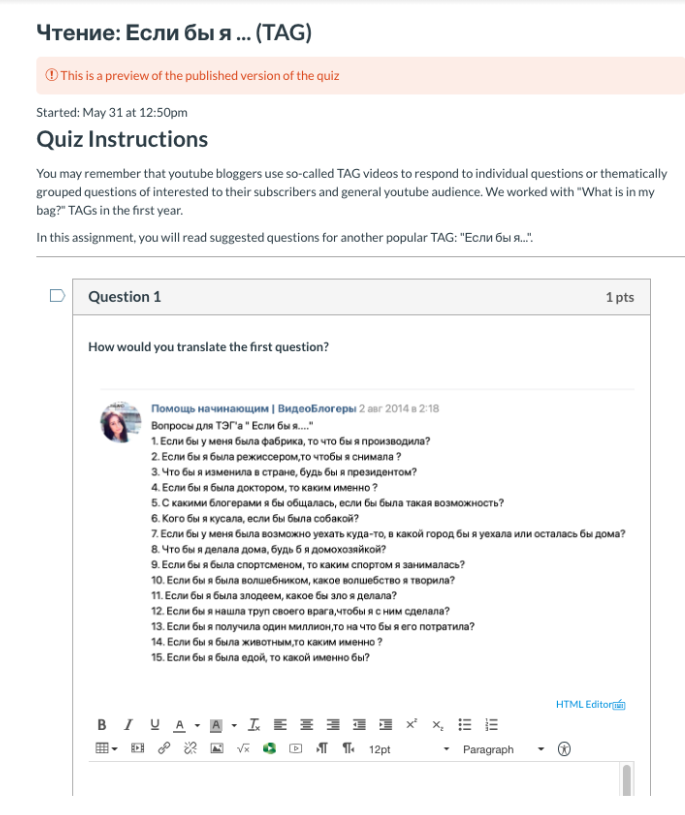

The first homework assignment related to the “If I were…” TAG in our intermediate course is a reading task based on the TAG’s questions, in which students translate those questions into English. In the screenshot below, you’ll see that the heading is in Russian, but the instructions in English contextualize the assignment. Then Question 1 of the assignment gives the students the list of the “If I were…” TAG questions, as found on the internet, and asks for the English translation of the first item, which would be, “If I had a factory, what would I produce?” We created the assignment using our course management system’s “quiz” format, but it is simply a homework assignment:

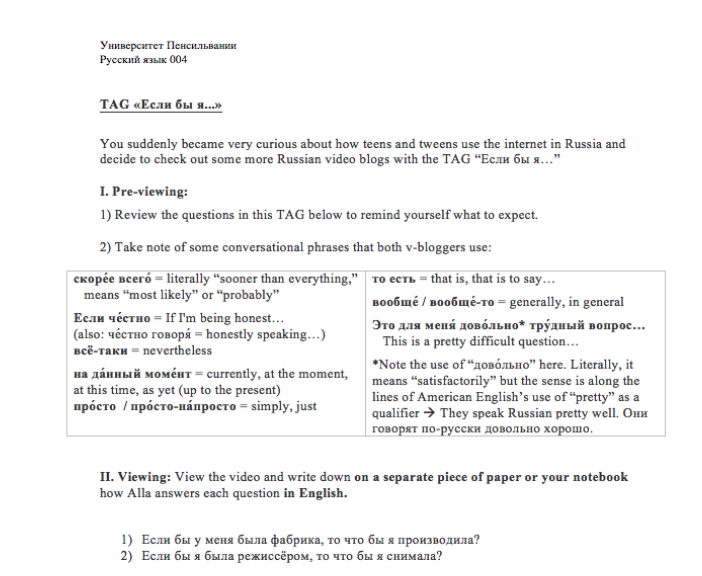

In the second homework assignment, students work with another video on the assigned TAG in great detail. The students again are asked to do translation work, but in this assignment, they translate a blogger’s spoken answers to the TAG’s questions into English:

The second assignment is followed by a post-viewing task, in which students correct their work:

In the third homework assignment, students write out answers to any 10 of the 15 TAG questions in Russian; they then receive written feedback from their instructor on them before recording their own TAGs. Depending on the topic of the TAG, the particular demands of the task and students’ level of proficiency, teachers can choose appropriate ways to scaffold these assignments.

OUR STUDENTS’ TAGS

Each TAG cluster culminates with work in the presentational mode of communication, as students create their own TAGs. Below are examples of our students’ TAGs, one from first semester, and one from fourth semester Russian. Even if you don’t understand Russian, you can get a sense of the students’ fluency and spontaneity, as well as similarities between the authentic TAGs above.

Video 4. Example of student-created TAG “What is in my bag?” Author: Yiyi (Yelina) Chen

Video 5. Example of student-created TAG “If I were…” Author: Westley Wendel

The additional examples below, one from first semester and one from fourth semester, are particularly successful in creating videos very similar to authentic TAGs and demonstrate a high level of personal investment in the videos. The first student recreated several TAGing techniques in her parody of the “What is in my bag?” video, including speeding up her recording, raising the pitch of her voice, using text pop-ups for “ads,” and gesturing. The second student also speeds up his rate of speech and successfully uses pauses and inflections typical for TAGs for dramatic effect. The content of his responses mirrors TAGing strategies used by video-bloggers. For example, he uses a variety of expressions typical for TAGs, such as, “Welcome to my channel!”; “As always, Vlad is with you.”; “Before I begin, I would like to say a couple of words about [what to expect].” Additionally, he shares a lot of personal information really fast and sometimes goes off topic, for example, to say that he is hungry.

Video 6. Example of student-created TAG “What is in my bag?” Author: Shruti Janakiraman

Video 7. Example of student-created TAG “If I were…” Author: Tathagat Bhatia

By designing tasks around the specific yet vast genre of TAG videos, we facilitate students’ use of the target language in ways that are linguistically, culturally, and contextually authentic and appropriate and allow for the students’ own personalization and creativity. We find that student-generated TAGs are on par with authentic TAGs and would be a great addition to the TAG culture; however, our students generally feel they would not want to share their TAGs beyond the classroom, although we were delighted that all the students above gave us permission to use their videos in this article! In both instructional clusters, students’ TAGs are used as the basis for formative assessment and in addition to content, accuracy, pronunciation, and fluency, are evaluated on how true they are to the genre of TAGs. Finally, we end each cluster of activities with a reflection task on student-produced TAGs that is either conducted in class or curated in the CMS.

CONCLUSION AND PLANS FOR IMPROVEMENT

Overall, the results of implementing TAG activity clusters into our curriculum have been very encouraging. We have been very happy with the level of comprehension and the nuance of analysis, as well as the quality of students’ TAGs. The results of an informal survey we conducted with our students in spring 2018 show that students respond positively to these activities because:

- They appreciate learning about the cultural practice of TAGing and enjoy using Russian in this real-life setting that is different from the classroom and is intended for an authentic audience.

- They find that TAGs allow them to express their personality in Russian and to improvise.

- Students find it challenging to speak without a script and make sure their speech is correct, while still sounding natural.

- 80% of students feel that their TAG videos were rather or very similar to authentic TAG videos they watched.

Furthermore, the survey results show that students found creating their own TAG to be a manageable task.

- On average students spent less than an hour making their TAGs, but usually re-recorded the video 3 or more times.

- As mentioned above, 90% of students do not feel comfortable sharing their TAGs with a larger audience and would not want to share their TAGs on YouTube, even without public access.

In response to a prompt for suggestions for improvement of the TAG clusters, students reported that:

- They would like to do more TAG videos and they had interesting suggestions for future TAGs. For example, recording TAGs with a partner and expanding the “What is in my bag?” TAG to different types of bags.

- They would like to have more time to watch more TAG videos and to have more guidance in finding and understanding them.

Our priorities in terms of implementing revisions and improvements to the TAG clusters center around the priming work that is done before the students make their own TAGs. Over the course of the three years that we have been working with TAG clusters, we have found that the more TAGs we watch in class and the more deeply we analyze them, the better our students’ TAGs are and the more enjoyable and rewarding the process is for the students.

Just like any other part of culture, especially of online culture, the popularity of individual TAGs, specific TAG questions, as well as general TAGing trends change quite rapidly over time. The TAG “What is in my (school) bag?” seems to have peaked in popularity a couple of years ago, and new TAGs such as “What will I do for New Year’s?” have taken their place. Working with TAGs requires constant monitoring of the new trends and adapting those trends into our curriculum, if and when it makes sense. Even more importantly, teaching our students to be aware of and keep track of these trends furthers their participation in this part of Russian-speaking culture. Because engaging with the target culture(s) has been such an important goal in our work with TAGs, we continue thinking about ways we could encourage our students to share their work outside of the classroom. For example, we have thought of trying to start a new TAG on Russian-speaking YouTube and see if we can generate interest in it, but, as mentioned, students are reluctant to post their videos there. We plan to continue prompting students about this and hope that as their interest and confidence grow, they might be willing to take this next step.