Study Abroad and Technology: Friend or Enemy?

By Senta Goertler, PhD, Associate Professor of Second Language Studies and German, Michigan State University.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.69732/KXKD8149

INTRODUCTION

“When I lived abroad, I couldn’t even call my parents let alone Skype or FaceTime with them. I had to send them a letter telling them that I met a man and we were going to get married.”

These are typical statements from study abroad leaders and language teachers, who lived abroad in the times of expensive global phone calls and without widespread Internet and email access. In many places of the world, our students have easy access to technology and to their friends and family at home, their favorite show, and their hometown news. Some might say study abroad students today never have to survive on their own abroad, because their support network is only a Skype call away. Robert Huesca (2013) provided a good personal narrative of the differences of his recent abroad experience with experience in the pre-technology age. This availability of home through the Internet can limit language contact and cultural immersion (cf. Trentman, 2013).

Before I discuss the advantages and disadvantages of technology use for language learning and the development of intercultural competence as it relates to experiences abroad, I will provide an overview of the state of study abroad in general. In the later section of this article, I will share how I implemented a model of using technology developed by Rachel Shively (2010) for two courses taught while abroad and a course-sequence at home. In those sections I will showcase what worked and what did not.

STATE OF STUDY ABROAD

While the number of study abroad participants is steadily increasing—from 62,000 in the late 80s to almost 290,000 in 2012—still only 9 percent of US undergraduates study abroad before they graduate (Institute of International Education, 2014). While in the past, the typical study abroad participant was a junior in the Humanities, today’s students are increasingly from the STEM fields. This diversification of study abroad participants poses its own challenges to study

abroad coordinators. From 2011 to 2012 STEM field participation in study abroad grew by 9 percent. But it is not just about who chooses to study abroad, but also what they do. In the past, students often spent their junior year abroad, enrolling at a university abroad, taking classes, and living in the dorms or with a host family. Today students often not only live, travel, and study in the abroad destination, but also complete guided internships; some abroad programs do not require students to take classes at all. Instead, they can complete an internship or a service-learning project. And while the year-long program used to be the norm, it is now the exception. Only 3 percent of study abroad participants go on programs that are a semester or longer. 60 percent of the programs are 8 weeks or shorter. Study abroad destinations are still primarily in Europe and increasingly in English-speaking countries or in English-speaking contexts such as studying Engineering at a German university in English.

Study Abroad Through Michigan State University

To showcase the diversity of study abroad programs, let me provide an overview of study abroad programs at my own institution. Michigan State University is a leader in study abroad, consistently ranked as one of the 3 largest study abroad providers in the US (MSU, Study Abroad, 2015). MSU offers more than 275 programs in more than 60 countries on all continents ranging from one week to an entire academic year (MSU, Program Search, 2015). 20 of the programs are offered at least partially in Germany (see Table 1).

Table 1. Study Abroad Options in Germany for MSU Students.

| Place(s) in Germany | Topic | Type | Length | Language |

| Munich, Dachau | Music, Art and Language in Bregenz, Austria | Faculty-led program with excursions | 5-weeks | English |

| Berlin, Dresden | Accounting and Financial Reporting in the Global Economy | Faculty-led tour | 2-weeks | English |

| Heidelberg, Munich | EuroScholars Research Abroad | Student research project in collaboration with host researcher | 1 semester | English |

| Freiburg | Academic Year in Freiburg – (almost) all subjects | Study at the university + local program office and some program courses | Academic year – 52 weeks | German |

| Hannover | Engineering in Hannover | Study at the university | 1 semester | English |

| Regensburg, Jena | Europe at War: Politics, Love and Conflict | Faculty-led tour | 5 weeks | English |

| Nürtingen, Dortmund | European Planning and Practice: Urban Redevelopment | Faculty-led tour with international workshop | 4 weeks | English |

| Jena | Friedrich Schiller University in Jena – (almost) all subjects | Study at German university | 1 semester | German |

| Mayen (Jena, Dresden, Berlin) | German Language and Culture in Mayen | MSU-faculty led language and culture program + trip | 5 weeks | German |

| Berlin | Independent Internship | Independent internship with or without language class | 2 months | English |

| Berlin | Independent Internship | Independent internship with or without language class | 3 months | German |

| Munich | MBA Program | Collaborative project across Europe with base in Munich | ? | English |

| Düsseldorf | Molecular Biology Research in Düsseldorf, Germany | Mentored research experience | 11 weeks | English & German |

| Stuttgart, Heidelberg, Singen | Packaging Logistics in Europe | MSU-faculty led tour and course | ? | English |

| Aachen | Mechanical Engineering at the RWTH-Aachen | Independent study + language class | 12 weeks | English & German |

| Stuttgart area | Teaching Internship in Germany | Internship | 3 weeks | German |

| Konstanz | University of Applied Sciences Konstanz (Business) | Study at the university | 1 semester | German |

| Frankfurt, Cologne | Dairy Husbandry & Environmental Stewardship in the Netherlands & Belgium | MSU-faculty led tour | 2 weeks | English |

| Berlin, Munich | A Creative Journey: From Barcelona to Berlin | MSU-faculty led tour | 5 weeks | English, German, Spanish |

| Berlin, Frankfurt, Munich | Renewable Bioenergy Systems – Sweden | MSU-faculty led | ? | English |

In looking at the above programs offered by MSU, some of which include Germany as a destination, the average length is 17 weeks, ranging from 2 weeks to 52 weeks. 11 of the 20 programs are offered in English only, six in German only, and three in both English and German. In the later part of this article, I will discuss pre-departure technology-enhanced tasks for the four German-program sponsored study abroad programs as well as in-country technology-mediated awareness raising tasks during the year-long study abroad program.

FACTORS INFLUENCING STUDY ABROAD

Let me now turn to learning during study abroad. There has been a lot of research conducted on study abroad experiences (for some summaries see for example Kinginger, 2011, 2013). The results on language learning during study abroad have been mixed, in part because of methodological differences but also due to the interplay of various factors. Some of the factors that have been studied are: age, gender, race, ethnicity, identity, initial language proficiency, living situation, program type, length of stay, language contact, language use, and language access. The research suggests that many factors in the list have an impact on language access and (therefore) language use, which in turn likely impacts language learning. For example students with higher initial language proficiency have better access to conversations in L2 and are more likely to be able to maintain a conversation in L2, thereby increasing interaction, which in turn increases language development. It is our task then, to positively influence the factors contributing to language access and use and assist students in maximizing their language contact.

TECHNOLOGY AND STUDY ABROAD

Technology Hindering Study Abroad Success

As mentioned before, technology has been seen as the enemy of an authentic study abroad experience as students listen, read, and watch entertainment and news from their L1, socialize with home through social media and technology-mediated communication, and they may only reflect on their cultural and linguistic experience in their L1 with members of their L1 community. All of these aspects can mean that they never fully engage with the community, the language and the culture. Trentman (2013) found that learners used more of their L1 than their L2 in part because of all the technology-mediated L1 communication.

Technology Supporting Study Abroad Success

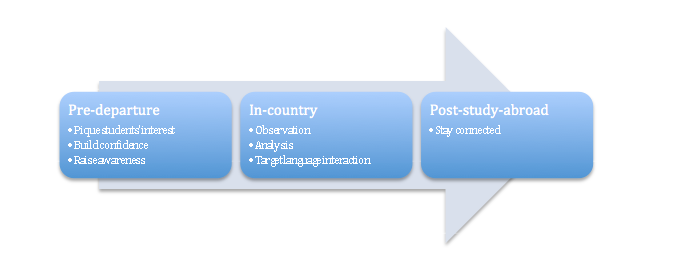

On the other hand, as Shively (2010) has showcased, technology can also be used to the students’ advantage pre-, during, and post-study abroad. Before the students go abroad, technology makes it possible for them to connect with the target community, see it, and engage with it. Students may google-earth the place they will live and search the Internet for available resources they might use (e.g. a local lacrosse team). Students can engage in online communities related to the community they will live in (e.g. Facebook groups, blogs, etc.). In addition they can read the local newspapers and watch the news to know, what topics are important to the people in the community and learn more about their perspectives. Through telecollaboration with the target community, they can practice their (intercultural) communication skills in advance and get to know members of the target communities, both of which should ease their transition to the target community and provide them with more language contact. By using the same technologies that allow students to disengage from the local community while abroad, we can help them engage with it before they depart. Through technology, they can gain access to the community, use the L2 and have an opportunity to further develop their L2 skills.

During study abroad, technology’s facilitative role in everyday life can help support interaction. For example purchasing a train ticket online or at the ticket machine may be less threatening than purchasing it through a real person, especially a real person on the phone. Computer-mediated communication tools allow students to engage in slowed-down communication with members of the L1 community. They can make plans to meet via text message rather than arrange a meeting on the phone. If you studied abroad in the last millennium, you know how terrifying it was to make phone calls. Through their smart phones, students today have easy access to maps, online dictionaries or dictionary apps, etc. If they encounter something they do not understand, they can take a picture of it, and ask someone for help.

In addition to these very practical uses of technology for survival and decreased anxiety and cognitive demand, technology can also be used to raise awareness and increase noticing. For example Ducate and Lomicka (2015) asked students to take pictures of items in the culture to reflect on them and thereby increase cultural knowledge and reflection. As Shively (2010) has outlined, students can also use technology to become their own language and culture researcher. For example students can complete mini-ethnographic research projects or small-scale linguistics analysis by recording interactions and later analyzing them. Students can also use technology to plan language tasks, such as rehearsing and recording answers to common questions. In addition to using technology for analysis and practice, students can also use technology for reflection. Blogging is an excellent opportunity to reflect on their experience abroad and receive feedback from others (Elola & Oskoz, 2008).

Post study abroad students can take advantage of the same tools that allowed them to get initial contact with the target community to extend their stay. By continuing to communicate with their new friends from the target community, engaging with entertainment and news from the community, students stay active with the L2 and C2. This will increase their language contact and may decrease language attrition.

Figure 1 summarizes the learning model put forth by Shively (2010). In addition to this model of technology use to maximize study abroad, the Center for Advanced Research on Language Acquisition at the University of Minnesota has published an excellent student and teacher guide on “Maximizing Study Abroad.” This guide provides excellent reflective and analytic tasks for pre-, during, and post study abroad. In relation to technology, Rachel Tuft also shared some practical advice on how to use technology to your advantage and how to not use technology in order to avoid pitfalls (Tuft, 2013).

PUTTING THEORY INTO PRACTICE

In the following section, I will share three curricular changes I have made before and during study abroad to implement the previously discussed affordances of technology. First I will share changes we made to our second-year curriculum, the minimum language level students need to complete before they are allowed to participate in our German-program sponsored study abroad programs. Next I will share how I applied Rachel Shively’s model to two sheltered immersion courses during a year-long study abroad program.

Get Them Hooked and Prepared Through Your Curriculum

Our second-year curriculum is a threshold in several ways: (1) it is the first level of courses that count toward the minor; (2) it is the level that needs to be completed to participate in study abroad; and (3) for many students it is the last course they will complete as, with it, they will likely have fulfilled their language requirement. Our second-year program uses a textbook that is organized by geographical units. The focus of each book chapter is a different German-speaking community. To enhance the visibility of our study abroad programs, we decided to replace two chapters per semester with in-house created modules on our study abroad destinations. After one year of implementation, our summer study abroad program had more applicants than available openings, and our year-long program tripled enrollments. In short: we think the changes worked.

The units were structured in the same way as the chapters of the book.

-

- Day 1: Introduction to the city and its history

- Day 2: Famous people from the community

- Day 3: Structure in focus 1

- Day 4: Article about something unique about the city

- Day 5: Structure in focus 2

- Day 6: Literary piece related to the city

- Day 7: Videoblog from people who live(d) in the city

- Day 8: Synthesis

These chapters gave the students a first impression of the town and may have sparked their interest. For example one student majoring in sustainability, who was not a German major or minor, learned about Freiburg and the major role the town plays in developing renewable energy sources and practicing a sustainable life-style. This encouraged her to apply for the program and become a German major. One of the modules was planned for the same week as the study abroad fair. As homework, students were assigned to attend the study abroad fair and in the weekly online discussion forum, to discuss the advantages and disadvantages of different Germany-related study abroad programs. Through those discussions, one of the students changed his mind from wanting to participate in the summer program to the semester program and eventually to participating in the year-long program. Simply learning through the modules and the discussion that it is possible to integrate a year-long program even with a major outside of the Humanities made him want to continue. In the Freiburg module, students saw videos about the neighborhoods, where the dorms for the Freiburg program are located. After viewing the videos and doing some online research, students picked the neighborhood they would prefer, and then we had a class debate about the advantages and disadvantages of different neighborhoods. Not only did this discussion prove very helpful, but when the actual Freiburg participants had to select their preferred dorm location, seeing the dorms and the neighborhood in advance also made the experience seem less intimidating for some students. One German major, who initially was not even willing to consider a summer program abroad (a problem, since study abroad is required for majors), ended up signing up for the year-long study abroad after she had seen three of the new modules. After the third module, she finally felt so comfortable about what to expect, that she signed up for the longest possible option. The most convincing portion of the module for students were the videoblogs. In the videoblogs, study abroad leaders and study abroad alumni talked about the towns and their experiences. Seeing that others had not only survived study abroad, but actually had a great time doing so, was yet another element that reduced fear and encouraged students to apply. Future research is needed to determine whether the students who benefitted from these curricular changes will have an easier transition to the country and greater learning success while abroad.

Awareness Raising Part 1: Applied Linguistics for Study Abroad

While leading our year-long study abroad program in Freiburg, Germany, I taught one course per semester. The course in the first semester was an applied linguistics course for study abroad students. In the course, we explored the following questions: (1) What makes up a language? (2) How is language really used? (3) How is the first language learned? (4) How are second languages learned? (5) How does language develop during study abroad? (6) How can we maximize the benefits of study abroad for language learning?

The students read German journal articles, worked through the student handbook for “Maximizing study abroad,” completed an applied linguistic empirical research study related to one of the 6 topics, completed weekly language tasks, and reflected on those tasks in a weekly blog post and commented on the posts of others. Here, I will focus on the language tasks and the blog posts. Naturally, all tasks and materials (except for the handbook) were in German.

Students completed the following types of tasks:

- Reflections

- Comparisons

- Ethnographies

- Genre analysis

Over the course of the 11 weeks, they posted their responses, read their peers’ responses, and commented on each other’s posts.

Table 2. Awareness Raising Tasks

| Week | Task Type | Type |

| 1 | Reflection | Complete the self-assessment tasks in the handbook and then answer the following questions on the blog: What are your goals for this year? What are your current competencies? How will you reach your goals? |

| 2 | Comparison | Record a conversation between a native speaker you are familiar with and yourself. Transcribe the audio recording. Analyze the recording focusing on differences and commonalities between you and the NS. Post a summary of those differences and commonalities online. |

| 3 | Comparison | Record your spontaneous answer to the question “What do you think about the NSA scandal?” Then research German and American perspectives on the scandal. After your research, record your answer again. Transcribe the recordings and compare your recordings. Post a summary of those differences and commonalities online. |

| 4 | Genre analysis | Follow the link to the speech given by the university president. Each student is assigned 5 minutes to transcribe. Once the entire speech is transcribed, decide on a linguistic research question and answer the question using the transcript as your data source. Post the results of your analysis on the blog. |

| 5 | Ethnography | In pairs you are assigned places to visit. Each pair is assigned a place, that you typically do not frequent (e.g. sports bar, kindergarten, youth center, public pool, etc.). Go to the place, observe how people are interacting, especially how people enter and exit conversations. Try to enter the conversation by mimicking what you had observed. Write a blog post summarizing what happened and reflecting on what worked and did not work and why. |

| 6 | Genre analysis | Academic journals are a special genre. Take a close look at the article to be read for the week. How is the article structured? What linguistic features do you notice? How is this different or the same from academic journal writing in the US? Write a blog post summarizing your findings. |

| 7 | Comparison | This week you have your advising meeting, which will be audio-recorded. Transcribe the audio and analyze the commonalities and differences between your and your advisor’s speech. Post a summary on our blog. |

| 8 | Ethnography | This week we will go on an excursion to the senior center in a small village. Observe how people interact and try to enter the conversation based on your observations. Write a summary of what happened and reflect why you were (not) successful in entering and maintaining a conversation with the seniors. |

| 9 | Comparison | Record a conversation between you and another NNS – ideally from another culture and language. Transcribe the audio recording and compare your speech with that of the other NNS. How does your proficiency compare to that of your interlocutor? What elements of marked language can be attributed to your respective L1/C1s? Which to the general acquisition process? Post a summary in the blog. |

| 10 | Reflection | Think back (and ask your parents) about your first language acquisition process. How did you learn it? Was there something special or unique? How did it compare to your learning of other languages? Post a summary on the blog. |

| 11 | Comparison | You wrote a narration as part of your placement exam in September and also wrote a narration in-class today. You will be given a copy of both writing samples. Type them and correct your errors. Post the samples with the marked corrections online. Reflect on the differences between the two samples. What did you learn? What are you still struggling with? |

The technology served three purposes in these activities:

(1) the technology allowed us to gather data and rely on recordings rather than our memory, which should have increased noticing;

(2) the blog allowed the students to reflect on their experiences and the things they noticed;

(3) the students could see the commonalities between their own and the findings of other students through the community aspect of the blog.

The students noticed many differences, but unfortunately without further pre- and post-task facilitation they were not always able to discover the most salient differences. For example in the last task, students noticed their weaknesses with adjective endings, but often missed the more problematic issue of lexical choice.

Awareness Raising Part 2: Intercultural Competence for Interns

In the second semester, several students completed an internship and enrolled in a course on intercultural competence training and reflection that supported their experiences as interns. The students completed about 150 hours at the internship sites. The sites ranged from educational settings to non-profits to business settings. At the end of the course, students had to create a video project about their internship site, their internship, and their experience. During the course of the semester, students wrote weekly blog posts and responded to each other. The blog posts can be divided into three phases:

- The internship (1-3)

- Weekly intercultural observations (4-12)

- Evaluation (13-15)

The second phase was intended as an awareness-raising phase to support the internships and learning. Every week, students were asked to summarize what they had done that week, describe their challenges and successes, and reflect on what they could do better to overcome the challenges and be more successful. The instructions did not specifically mention culture, so that students would not focus on stereotypical intercultural conflicts, but rather on conflicts in general. By having the group blog, we hoped that students would see which types of conflict were common across people and sites, thus helping them identify potentially intercultural conflicts, and which types were more unique and therefore more likely to be interpersonal. Interestingly, while students were able to see common issues – in fact, they were complaining sometimes that the blogs were boring because everyone wrote the same – they did not make the connection, that some of those issues may have an intercultural conflict as a source. For example, one particularly problematic issue was that the American interns repeatedly showed less independence and self-reliance than is expected of Germans in this age group and as interns. It was not until we discussed this cultural difference in class, discussed solutions to the issues related to their lack of independence, and role-played through several situations that some students were finally able to adjust and successfully display more independence and self-reliance. This resulted in more successes and greater satisfaction for them and their supervisor.

CONCLUSION

The original question of whether technology helps or hinders study abroad success can be answered both ways: it can be both detrimental and helpful for study abroad. On the one hand, by making the home culture easily available, the Internet may take away from the cultural and language immersion. On the other hand, I hope to have shown how technology can also be used successfully to prepare for study abroad and maximize the study abroad experience through facilitated interactions and technology-mediated awareness raising activities. However, the awareness raising tasks need to be paired with pre- and post-task facilitation by an expert in order to assist learners in noticing problematic (language) behavior and being able to adjust the language production or cultural interaction to the norms of the community.

REFERENCES

Ducate, Lara and Lara Lomicka. “Exploring Intercultural Awareness in Diverse Language Learning Contexts.” Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Computer-assisted Language Learning Consortium. Boulder, Colorado. May 28, 2015.

Elola, Idoia, and Ana Oskoz. “Blogging: Fostering Intercultural Competence Development in Foreign Language and Study Abroad Contexts.” Foreign Language Annals, 41, 3 (2008): 454-477. Accessed March 15, 2013.

Huesca, Robert. “How Facebook Can Ruin Study Abroad.” The Chronicle of Higher Education, January 14, 2013. http://chronicle.com/article/How-Facebook-Can-Ruin-Study/136633/

Institute of International Education. “Open Doors. US-Study Abroad.” Accessed January 31, 2015. http://www.iie.org/Research-and-Publications/Open-Doors/Data/US-Study-Abroad/Infographic

Kinginger, Celeste. “Enhancing Language Learning in Study Abroad.” Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 31 (2011): 58-73. Accessed January 31, 2015.

Kinginger, Celeste. “Identity and Language Learning in Study Abroad.” Foreign Language Annals, 46, 3 (2013): 339-358. Accessed on January 31, 2015.

Michigan State University. “Program Search.” Accessed May 28, 2015. http://studyabroad.isp.msu.edu/programs/

Michigan State University. “Study Abroad.” Accessed June 3, 2015. http://admissions.msu.edu/academics/studyabroad.asp

Paige, Michael, Andrew Cohen, Barbara Kappler Mikk, Julie C. Chi, and James P. Lassegard. Maximizing Study Abroad: A Students’ Guide to Strategies for Language and Culture Learning and Use. Minneapolis: Center for Advanced Research on Language Acquisition, 2003.

Shively, Rachel L. “From the Virtual World to the Real World: A Model of Pragmatics Instruction for Study Abroad.” Foreign Language Annals, 43, 1, (2010): 105-107. Accessed January 31, 2015.

Trentman, Emma. “Arabic and English During Study Abroad in Cairo, Egypt: Issues of Access and Use.” The Modern Language Journal 97,2 (2013): 457-473. Accessed January 31, 2015.

Tufts, Rachel. “The Do’s and Don’t’s of Technology and Study Abroad.” Go Overseas, April 10, 2013, http://www.gooverseas.com/blog/dos-and-donts-technology-and-study-abroad