A Grassroots Virtual Exchange between Pre-Service Language Teachers and Language Students

Paul Sebastian |

Carmen Fernández Juncal |

Benjamin Souza |

Maddalena Ghezzi Maddalena GhezziResearch Scholar Universidad de Salamanca |

Roberto Rubio Sánchez Roberto Rubio SánchezResearch Scholar Universidad de Salamanca |

One of our main goals as world language educators is to push our students beyond their linguistic and cultural comfort zones. Two ways in which we do this include 1) getting the students outside of the classroom and into the real world and 2) bringing the real world into the classroom. This broader vision of what we do and why we do it is sometimes eclipsed by unnecessarily long grammar explanations or comforting choral exercises. To be fair, grammar and audio-lingual activities both have their place in the language curriculum. The problem is that to move beyond those nuts and bolts, we must be willing to try something new and to ask our students to join us in the adventure. For these reasons, advances in the area of computer-assisted language learning (CALL) have had a major impact in world language education. One of the main goals of CALL has been to merge the classroom world with the culturally and linguistically rich world beyond it. Of the many CALL tools and techniques that do this, virtual exchange has shown great promise at accomplishing this. Virtual exchange, also referred to as telecollaboration, “involves bringing together groups of learners from different cultural contexts for extended periods of online intercultural collaboration and interaction” (O’Dowd & O’Rourke, 2019, p. 1). Within these parameters, an increasing number of exchanges are being carried out, each with its own variation of who, how, how much, and why. In this article, we discuss the grassroots creation of a virtual exchange program that brought pre-service Spanish teachers in Spain together with novice and intermediate level Spanish language students in the United States. Reflecting on our various educative and facilitative roles in this process, we adopt an action research approach in our reflection of what worked and what we wished we would have done differently. Because exchanges, by their nature, involve two or more parties, this article has been organized in a way that allows for both partners to share our experiences in the creation of what we call the Proyecto IDEA or Intercambio Digital Europeo-Americano.

Finding Your Virtual Exchange Partner(s)

The creation of any virtual exchange begins with identifying and establishing an appropriate and mutually benefitting partner or set of partners. Our particular partnership began with a pair of problems; the language learners in the United States needed more opportunities to use the target language in linguistically and culturally rich environments and the pre-service Spanish teachers in Spain needed experience working with actual students who were learning Spanish as a second language. O’Dowd (2018) calls this kind of approach to virtual exchange a practitioner-led approach because of the level of involvement of the orchestrating faculty members. This symbiotic relationship was also apparent in the overarching project goals that guided many of the later logistic and pedagogical decisions we made in designing the exchange. Table 1 shows the partner specific goals that each of our institutions articulated for what we hoped our students would accomplish.

| Appalachian State University | University of Salamanca |

| To improve interpersonal communicative ability by speaking with native Spanish speakers | To gain practical experience of computer assisted language learning tools, as well as other theoretical contents introduced in the classroom setting |

| To increase motivation to continue learning about the target language and culture by providing authentic communicative experiences | To facilitate subsequent reflection and discussion of the challenges and benefits of online teaching |

| To reinforce knowledge of the suggested session topics with accompanying grammar and vocabulary themes | To increase motivation by introducing students to authentic teaching experiences |

Other goals were broader in nature and served as outcomes we hoped both populations of students would meet. The shared goals for the program included the following: Improve students’ digital literacy skills through a hands-on approach with communicative technologies. Enhance students’ autonomy in their path as second language learners and teachers, engaging them with an experiential and interactive practice (Román-Mendoza, 2018). Improve students’ intercultural competence through open-ended conversation on a variety of suggested and naturally occurring topics. Strengthen the professional relationship between our two universities by identifying ways for our students to connect in mutually beneficial ways. The goals were complementary in nature and, together with the overlapping program goals, helped us to create a mutually beneficial partnership. It was only after this essential component had been worked out that both parties began to discuss other details, including which platform to use, number and length of sessions, scheduling, tasks, and other typical matters of virtual exchanges. Once the matter of mutual benefit had been met, the other components of the exchange seemed to fall into place almost naturally. Apart from organic partnerships, there are other, often less time-consuming ways to connect language students with native speakers. One such option includes the use of commercial programs like Boomalang, TalkAbroad, or Conversifi. Although cost and limited flexibility of these programs can be a deterrent, the support they provide for grouping, scheduling, and troubleshooting can be attractive for those looking to get started with virtual exchanges (Thompson & Martinsen, 2018). The advantages of such models are certainly appealing but, in the end, we opted for a more grassroots approach for our virtual exchange project. The second option, and the one that is more aligned with the overall linguistic and cultural goals of virtual exchange, is the organization known as UNICollaboration. The organization provides virtual meeting spaces and partnering tools for those looking to get started with their virtual exchange projects. Although this can help to remove some of the legwork in building partnerships, collaborations are limited to those who are actively seeking such opportunities and who have reached out to the organization to share their information. Thus, given the limitations of both of these possible routes to virtual exchange, and since there had already been attempts to establish a working relationship between our two institutions, we opted to start from scratch. The result, at least in our experience, has turned into a strong, mutually beneficial virtual exchange partnership. The specifics of how each partner entered the virtual exchange partnership are outlined below.

Appalachian State University: Finding a Partner

In 2013, Appalachian State University put into place an institutional-level initiative which focused entirely on the idea of global learning. Over the subsequent five years, funds and other forms of institutional support were made available to members of the campus community in exchange for their efforts to engage students in “diverse experiences at home and abroad” and “to increase their knowledge of global issues, regions, and cultures” (Appalachian State University, 2013, p. 2). It was thanks to the support of this initiative that a member of the Appalachian community was able to travel to the University of Salamanca to meet with individuals interested in finding ways to connect our two campuses. No immediate projects were launched after that first meeting but the ground had been laid for follow-up discussions to take place. About one year after that initial meeting, I had a chance to revisit the idea. While attending an academic conference held that year at the University of Salamanca, I met with faculty in the Masters in Spanish as a Second Language program to discuss the possibility of a virtual exchange. After a series of subsequent email introductions, we were eventually put into contact with two professors who taught a CALL course as part of the program in Salamanca. Thus, through a multi-step series of formal and informal introductions that spanned more than a year, six professors, three from Appalachian State University and three from the University of Salamanca worked together in the fall of 2018 to pilot the virtual exchange project.

University of Salamanca: Finding a Partner

In 2013, the University of Salamanca received an institutional visit from a delegate from Appalachian State University. Previously, exchange agreements for graduate students had been established to the great satisfaction of both parties. As a natural consequence of the relations between both institutions, it was decided to go one step further: virtual exchanges. The Master’s Degree in Teaching Spanish as a Second Language welcomed the initiative in one of its courses: ICT in language teaching. The team from the University of Salamanca, led by two professors, tackled the challenge. They were aware of the potential difficulties: the pairing of tutors and tutored, the use of the telecollaboration tool, the creation of topics, and other programming challenges. Still, figuring out the complexity was worth it because it was seen as an opportunity for future Spanish language teachers to develop their skills, working with students from other cultural backgrounds with the convenience of doing so from their home campus. Under the direction of a teacher from the Spanish Language Department, this project was presented as a proposal for teaching innovation during the 2018-2019 academic year at the University of Salamanca. The plan was evaluated by a double-blind peer review system and approved with a high qualification. Thus, what began as a simple conversation about an idea, had grown into an official, institutionally approved program.

Figuring out Logistics

Finding a virtual exchange partner is only the first hurdle to a long line of complex challenges. Our first planning meetings as a newly formed partnership were spent discussing specific platform options, schedules, dates, orientations, online tutorials, participant recruitment, and consent forms. At the same time, we were sketching out conversation topics and tasks that gave structure to the exchanges and yet were flexible enough to allow natural conversation to occur. The following sections provide a deceptively organized overview of this multi-tiered planning process.

Selecting a Platform

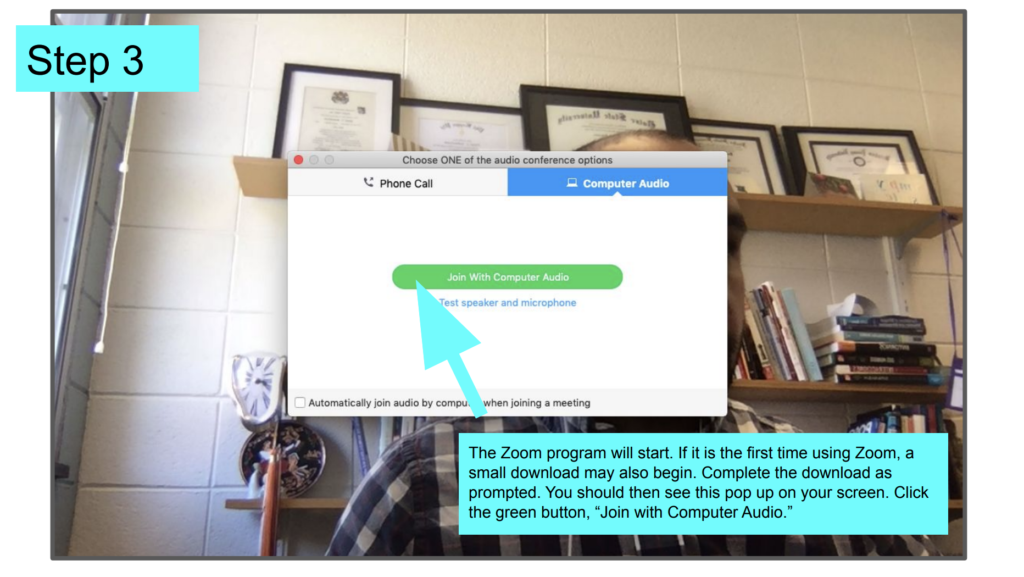

In selecting the particular technologies for the project, we wanted tools that allowed us to implement a mostly autonomous experience. At Appalachian State, the campus community had recently been provided access to professional accounts for Zoom, a Skype-like videoconferencing platform. Not only did Zoom provide us the basic necessity of stable video and audio connections, it also offered extra features including the ability to screen-share, record sessions, and see other group members in a convenient gallery view format. For these reasons, we chose Zoom as the platform for the exchange and then set out creating tutorials and other supportive materials to orient the students to the virtual space. Figure 1 shows one of the steps from the Zoom tutorial which was delivered to all participating students as a Google Slides presentation.

Providing Orientations and Tutorials

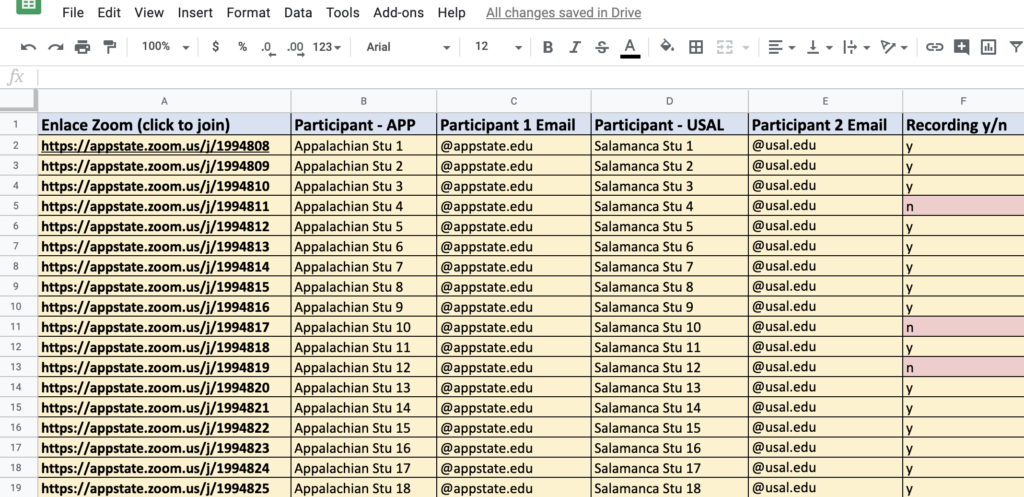

Along with the Zoom tutorial, students were provided with a shared Google document which contained important information for the exchange including names of each of the students in each group, contact information, and most importantly, a Zoom link to the Appalachian State student’s Zoom personal meeting ID. Figure 2 shows an example of the shared Google document but the Zoom links and student names have been randomized and anonymized to protect the identity of the participants.

To obtain the meeting links, the Appalachian State students were asked to log into their Zoom accounts and send their personal ID meeting link to one of the coordinators of the program. Then, when it was time to initiate each of the Zoom sessions, the students could return to the shared document to click on the meeting link. In addition to the static tutorial sent out to students, the program coordinators organized in-person and virtual orientation meetings to provide an overview of the goals of the virtual exchange and to introduce students to the Zoom platform. These short sessions provided opportunities for students to ask questions related to scheduling, recording sessions, conversation topics, and to voice other logistical concerns. The sessions also provided a space for students to admit their apprehensions about communicating effectively in the virtual exchange environment. Appalachian State students expressed worries about their low language proficiency levels and the University of Salamanca students expressed concerns about keeping students engaged and how to best adapt to students’ needs and expectations. In response, we did our best to instill confidence in the students and emphasized the fact that the main purpose of the exchange was not to point out all of their shortcomings as language students or pre-service language teachers but rather, to give them an authentic communicative experience where they were free to make mistakes.

Scheduling

One of the key logistical decisions we made in planning the virtual exchange was to allow students to schedule the time for their individual sessions. The only requirement was that all five sessions needed to be completed within a two-week period which started in late March and ended in early April. We also asked that they try to space their sessions out evenly over that timeframe. On a couple of occasions, the project coordinators had to remind the students to keep their appointments with one another. Part of the problem here was that the Appalachian State students were participating in a volunteer capacity. That is, their participation was intrinsically motivated and stemmed from their desire to enhance their conversational ability. Because the University of Salamanca students’ participation was built into their course grade, there were fewer problems with their participation and attendance during scheduled sessions.

Grouping

Although the idea was to provide a one-to-one virtual exchange experience for our students, we were also open to trying out small group options where two or even three Appalachian State language students would be placed with one University of Salamanca pre-service teacher. This triad arrangement was necessary for only one of the 18 groups. However, one of the Appalachian State students in the triad decided not to participate in the virtual exchange afterall which left us with 18 one-to-one virtual exchange groups. The other consideration in group assignments was to place students who had not given their consent to be recorded together so as to avoid any conflicting desires of the students in the group.

Structuring the Sessions

For the pilot project we asked students to participate in a total of five thematically organized virtual exchange sessions. Each session was to last approximately fifty minutes with the last ten minutes being reserved for scheduling and planning for the subsequent session. Our goal with structuring the conversation sessions was to provide just enough guidance and direction in order to keep the conversation flowing. To do this, we opted for sessions that were structured around central themes that are commonly discussed in beginning and intermediate language classes. However, we were also clear with the students that they were free to discuss as much or as little of the provided prompts as they wanted. The reasoning for this was that we wanted students to feel free to converse at their own pace and about topics that they personally found interesting. We also wanted to leave enough room for the pre-service teachers to come up with their own ways to engage their partners in natural conversation. Table 2 shows the suggested conversation topics for each of the virtual exchange sessions.

| Session 1: Introductions | Basic personal information, likes and dislikes (books, foods, movies, activities), previous experiences with the target language and/or culture, experiences and comfort level with technology |

| Session 2: School | Experiences at the different levels of school (primary, secondary, post-secondary education), professors, classes, favorite subjects, comparing experiences in their respective academic programs |

| Session 3: Professional Goals | Future and/or current jobs and job interests, professional skills, job training, professional experiences, comparison of the employment outlook for young people in both cultures and countries and discussion of job market trends and access to jobs |

| Session 4: Everyday Life | Daily schedules, schedules, habits, holidays, festivals, celebrations, traditions, use of social media, use of technological tools and platforms |

| Session 5: Places of Origin | Where you were born, raised, where you live now, cities you’ve visited, kinds of houses where you live, linguistic and cultural characteristics of the community where you live, use of Google Street View to show each other some of these places |

Table 2: Suggested Conversation Topics for Sessions

Although we considered using task-based sessions and including specific questions for each group to work through, we felt that the five suggested themes above would lead to more natural and unscripted dialogue. Furthermore, it is common for language teachers to have to shape the learning experiences of their students given similarly broad parameters and so the sessions served as an authentic experience for the pre-service Spanish language teachers. Finally, the University of Salamanca students were also encouraged to use several digital tools and apps during the virtual exchange sessions in order to better understand their function and effectiveness.

Sustaining the Partnership

In addition to maintaining open communication before and during the pilot phase of the virtual exchange, we made it a point to come together for reflective conversations after the conclusion of the project. During these meetings we shared both formal and informal feedback that each partner institution had collected about the strengths and weaknesses of the exchange.

What Worked Well

One of the main contributing factors to the success of our exchange was the flexibility built into both the scheduling and the conversation topic components of the program. The key seemed to be in the balance between setting parameters and allowing students enough room to navigate the exchange at their own pace and in their own way. With scheduling, for example, students were free to set their own days and times for each of the sessions but they also knew that all sessions needed to be completed within the broader two-week timeframe. Similarly, the suggested conversation topics provided general ideas for discussion but they also allowed room for students to talk freely and naturally. Additionally, we were quite pleased with the functionality and overall reliability of the Zoom platform. A particular benefit of the platform was that students could connect from anywhere using almost any kind of device that had a microphone and a web camera. Finding themselves untethered from computer stations, students joined sessions from the comfort of their dorm rooms and sitting in campus cafes. Thus, both in regards to technology and curriculum design, flexibility turned out to be beneficial for the overall virtual exchange project. Allowing students to connect when, where, and how they wanted also required them to act autonomously throughout the exchange. This meant that, unlike the instant troubleshooting support that students might have in a controlled computer lab environment, they needed to resolve any issues on their own or communicate such problems with the coordination team. In the end, although there were a small handful of issues (most of which were related to technology), students seemed to handle this freedom quite well. Part of the reason for this may have been the time we spent preparing tutorials and meeting with students in the pre-exchange orientation meetings. Our positive results support similar projects which found these orientation steps to be most helpful when implemented during the early stages of the virtual exchange (Bohinski and Venegas Escobar, 2015). Another likely reason for success in this area was that students were willing to engage one another within a collaborative, social, and virtual environment. Unlike other exchange models with high levels of moderator presence (Méndez-Betancor, Wahls, Ariza-Pinzón, 2016) ours was designed to work without session moderators. Because of this, students were required to employ problem solving skills to overcome the technological and pedagogical challenges they encountered. The effect was enhanced digital wisdom (Prensky, 2012) and increased learner autonomy (Reinders & White, 2016). The last component that led to the successful virtual exchange was the dynamic relationship between our two partnering institutions. In many ways, the virtual exchange partnership was built like a good friendship. Since we had no particular deadlines to meet, we were able to take our time as we discussed the various details of the exchange. Furthermore, because we decided to begin with a pilot version of the program, we were more willing to take pedagogical and logistical risks. Guided by our shared commitment to action research, every decision was made with the thought that if something didn’t work out exactly as we’d hoped, we could pivot and implement change in the follow-up iteration of the exchange. Working together on such unsure ground can be challenging for any partnership, particularly if the relationship is formed quickly, or worse, randomly. But, because the entire project began with the slow formation of a strong partnership, we were able to work with the uncertainties of the pilot phase and reflect honestly about what went well and what needed to be improved.

Areas for Improvement

In our post-exchange discussions, we identified two aspects of the exchange that didn’t work as well as we hoped. The first was curricular in nature. Although the University of Salamanca students’ participation was tied to a graded component of their ICT in second language teaching class, the Appalachian State students’ involvement was purely voluntary. We hoped that with this arrangement we could identify students who were genuinely interested in participating. Although this was true for the large majority of the students, there were a few Appalachian students that needed regular reminders to participate. The quick fix implemented during the pilot was to find another language student who was interested in some extra conversation practice with a native speaker. Although this worked fine during the pilot, we decided that to avoid such scenarios in the future, participation in the exchange would be tied to a class grade for both institutional partners. The second unexpected complication had to do with the Zoom platform. After a few sessions had taken place, we began to receive feedback that some groups weren’t able to record their conversation sessions. Although there might have been other underlying factors, part of the problem might have been with the particular way we encouraged students to begin each conversation session. Rather than allowing students to start each session on their own, we asked students to use the shared Google document to click the meeting link for their group. As best we can tell, this was creating a way to bypass the login process for Zoom, thereby preventing the host partner from using the record function. By the time we had identified the problem it was too late in the exchange to implement any sweeping corrective measures and so we simply informed all the students that it was a known issue. This was unfortunate because part of the University of Salamanca students’ requirement for the course was to upload a recording to their teaching portfolio. Again, we were surprised by the students’ resourcefulness when we later heard that some had simply opted to record themselves using their mobile phone so that they would have something to submit to their portfolio. Not all students consented to having their sessions recorded and for those groups, alternative evidence was accepted for their portfolio assignments.

Conclusion

The pilot phase of the virtual exchange project resulted in a total of 90 virtual conversation sessions between language students at Appalachian State University and pre-service teachers at the University of Salamanca. Our action research approach to the design and implementation of this particular virtual exchange helped us to reflect carefully and critically about what worked well and what needed to be improved moving forward. Because our discussion here derives from our personal experiences having participated as coordinators and facilitators of the project, we cannot say that similarly implemented virtual exchanges will have the same results. What we can say, however, is that taking the time to establish a strong grassroots partnership was paramount to the success of our project. Because of this, we were better able to overcome the challenges that we encountered during the pilot phase of our project. The second important element to our exchange was finding the right balance between flexibility and structure and between autonomy and support. By building in more flexibility into the exchange, we also increased the level of autonomy that students needed in order to navigate unexpected challenges. In effect, this helped us bypass many of the perennial problems of virtual exchanges which tend to revolve around issues of logistics such as scheduling and technology (Helm, 2015).

References

Appalachian State University. (2013). Global learning: A world of opportunities for Appalachian students – Quality Enhancement Plan. Retrieved from https://qep.appstate.edu/sites/qep.appstate.edu/files/QEP-report-final_0.pdf

Bohinski, C. A., & Venegas Escobar, S. (2015, July). Teamwork, technology, and online collaborations. FLTMAG. Retrieved from https://fltmag.com/teamwork-technology/

Helm, F. (2015). The practices and challenges of telecollaboration in higher education in Europe. Language Learning & Technology, 19(2), 197–217.

Méndez-Betancor, A., Wahls, N., & Ariza-Pinzón, V. (2016, November). Beyond the walls of the classroom. FLTMAG. Retrieved from https://fltmag.com/beyond-walls-classroom-cultural-diversity-virtual-exchange-intercultural-competency/

O’Dowd, R. (2018). From telecollaboration to virtual exchange: State-of-the-art and the role of UNICollaboration in moving forward. Journal of Virtual Exchange, 1, 1-23.

O’Dowd, R., & O’Rourke, B. (2019). New developments in virtual exchange for foreign language education. Language Learning & Technology, 23(3), 1–7.

Prensky, M. (2012). From digital natives to digital wisdom: Hopeful essays for 21st century learning. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Reinders, H., & White, C. (2016). 20 Years of autonomy and technology: How far have we come and where to next?. Language Leaning & Technology, 20(2): 143-154.

Román-Mendoza, E. (2018). Aprender a aprender en la era digital. Tecnopedagogía crítica para la enseñanza del español LE/L2. London: Routledge.

Thompson, G., & Martinsen, R. A. (2018, November). Speak up! The top ten ways to connect your students with native speakers. Presentation given at the American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages (ACTFL) Conference, New Orleans, LA.