A Syntax Tree “Metativity”: A Collaborative Web3 Activity in the FrameVR Metaverse

By Elizabeth Enkin, University of Nebraska-Lincoln

DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.69732/CKTL9913

As language teachers, we are keenly aware of the important benefits that Web 2.0, the collaborative web, has brought to language teaching. From social media to audio and visual tools, Web 2.0 has allowed language instructors to develop meaningful activities that leverage digital communication. Now with the advent of newer emerging technological tools, we are also seeing the significant impact of the newest iteration of the web: Web3. Web3 can be thought of as both the spatial and intelligent web, thereby being characterized by collaborative 3D virtual spaces (also known as “metaverses”), as well as various generative and agentic AI tools.

In this article, I will describe a metaverse-based activity (or “metativity” as I call it) that I created and carried out with my students in my advanced-level Introduction to Linguistics course. This is a common class that is offered as part of the Spanish curriculum for majors and minors at many universities, as it is at mine. For me, the FrameVR metaverse helped to fill a pedagogical need I had in this class, which I will further discuss in the next section. Not only was Frame a free and creative solution, but it was also a convenient one, as it offered the benefits of a 3D environment without necessitating the use of VR headsets. Indeed, because Frame is a browser-based software, it is usable on any device, including laptops, touch devices (phones or tablets), and VR headsets. Since the pandemic, I have focused on making my class more of a paperless experience (for both organizational purposes for myself and my students, and as part of my instructional continuity plan), and I therefore ask students to bring their own devices (laptop or tablet) to class each day. My class and I were therefore able to remain in our classroom and use our own devices for the task. See below for an action shot from my metativity, and read on for more details.

Why Use FrameVR in Introduction to Linguistics?

I teach a 300-level Spanish course titled Introduction to Linguistics at my university. The class is both theoretical and practical, and focuses on linguistic analysis of the Spanish language in five main areas: phonetics and phonology, morphology, syntax, semantics and pragmatics, and historical linguistics. As noted above, I have focused on making the class more digital since the pandemic, and have moved to an activity-centered design as well. Students therefore work on problem sets in class that review the lecture materials, and I make these activities available via Google Docs.

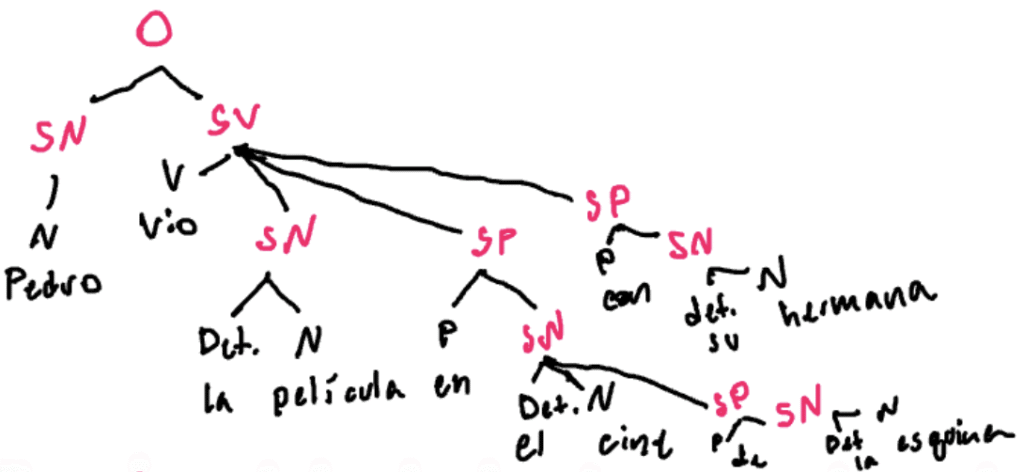

Google Docs allows users to collaborate on one document, which works well for many of my units, except for certain parts of the syntax section, where I ask my students to create syntax tree diagrams. These are tree-structured graphical representations of the grammatical structure of a sentence. I use these diagrams as a way to review grammatical relations in simple sentences (i.e., sentences that contain one event, or one conjugated verb – see a picture below of an example that was drawn by hand), and as a scaffold to more complex trees and grammar (in later units, we specifically review the use of the subjunctive in nominal, adjectival, and adverbial subordinate clauses, and I have students create tree diagrams for these complex sentences).

Tree diagrams, however, prove to be difficult to do with Google Docs as a truly collaborative activity because I cannot premake diagram pieces for my students, which they could then easily move around to form the tree. I reasoned that this would, indeed, be an excellent way to introduce, and practice, syntax trees. Otherwise, they can become somewhat tedious or dull, especially during a group activity, and students often prefer to simply draw the diagrams out by hand as it becomes easiest (on paper or on their tablet, as is pictured above). FrameVR therefore became an interesting potential solution as it offers a collaborative and gamified environment that would enable what I wanted for the task.

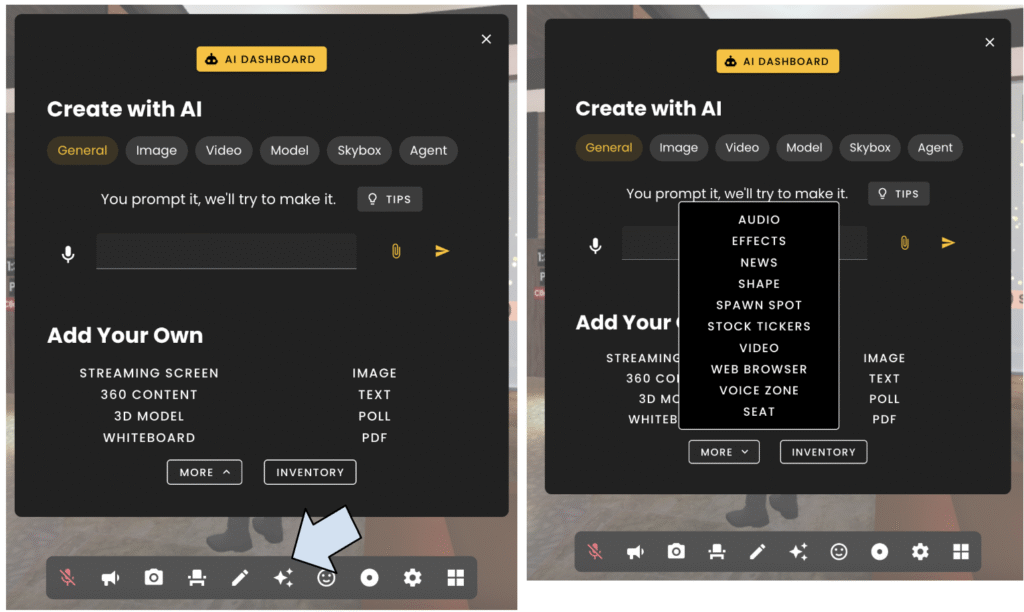

Although Frame is mainly intended as a 3D web conferencing platform, you can easily use the software when in a physical classroom setting by having all of your students mute their mics (click on the mic icon at the bottom of the screen when in Frame). Each 3D space (room) is conveniently shareable via a URL, and once in a room, users move around with their arrow keys and mouse. Frame also allows you to personalize rooms by adding various assets into them, such as interactive whiteboards, text labels or areas, 3D models, PDFs, videos, audio, and even embodied AI agents (essentially, an avatar). To add an asset into your room, simply use the “Creations” menu, which is accessible via an icon at the bottom of the screen: see the picture below. Each room can hold up to eight users at a time, which makes them very usable for group work. Importantly, anyone in a room is able to use (“edit”) the assets in that room. This feature allowed me to envision a digitally inclusive activity in the Frame VR metaverse for my students: a syntax tree metativity!

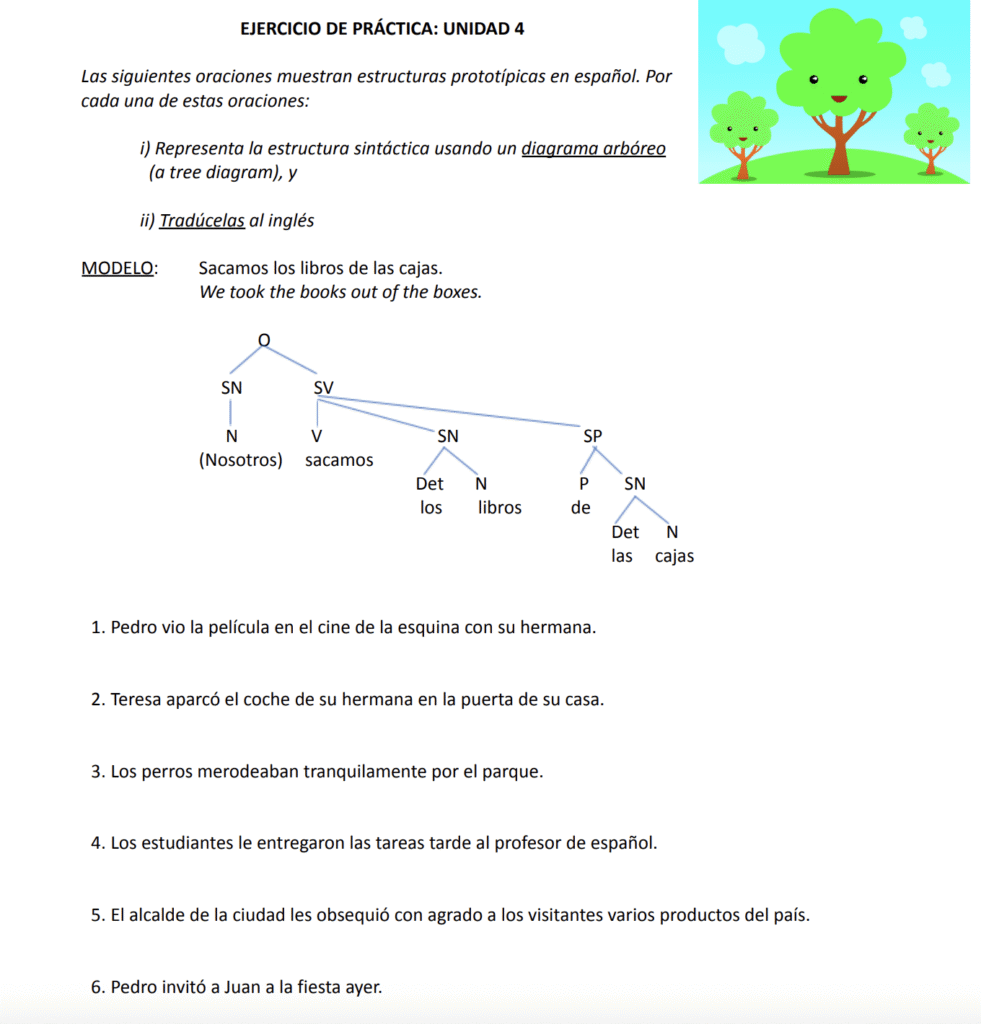

I aimed for my metativity to take about 10-15 minutes. I start this unit by explaining the syntactic phrases that group words in a sentence together: the noun phrase (“sintagma nominal”, SN), verb phrase (“sintagma verbal”, SV), prepositional phrase (“sintagma preposicional”, SP), and adverbial phrase (“sintagma adverbial”, SAdv). These phrases represent grammatical categories that constitute a sentence (“oración”, O), and they each break down into specific parts of speech as well. For example, an SP consists of a preposition (P) and SN, and that SN will also consist of parts, such as a determiner (Det) and a noun (N). By diagramming simple sentences in tree format, students are able to identify complements and modifiers, thereby also learning more about transitive and intransitive verbs.

My Syntax Tree Metativity

For my metativity, I divided the class into 3 groups, with 3-4 members per group. I created a worksheet (see a picture of the Google Doc below) asking students to create syntax trees for sentences in Spanish. I assigned either sentence #3, 4, or 6 to each group (we had completed trees for the first two sentences together as a whole class the previous day, and I had used #5 as a warm-up that day). I called each sentence (#3, 4, or 6) a “puzzle.”

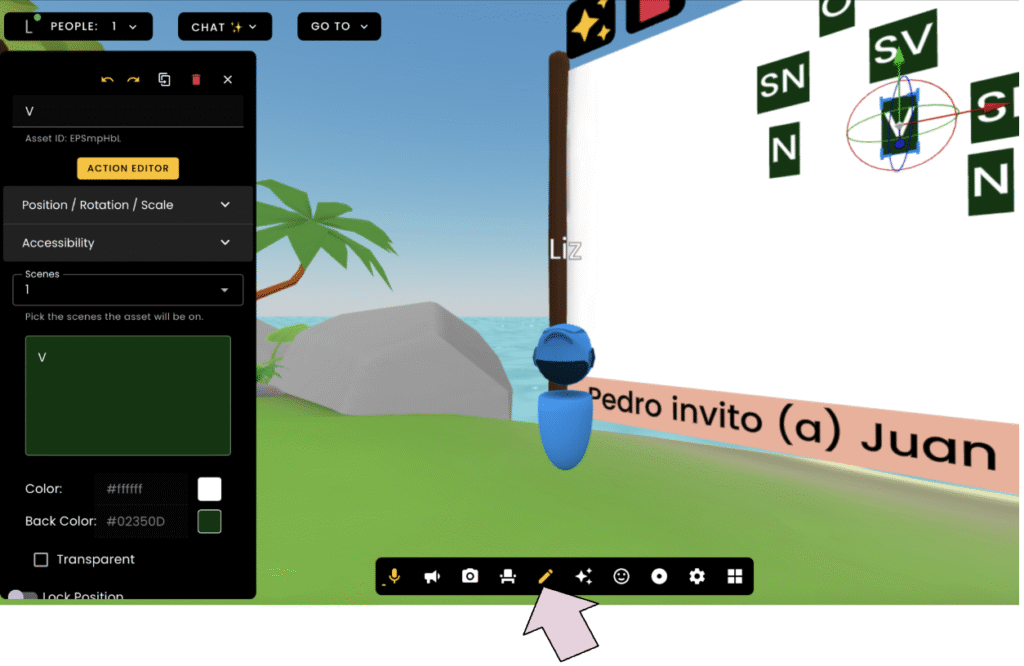

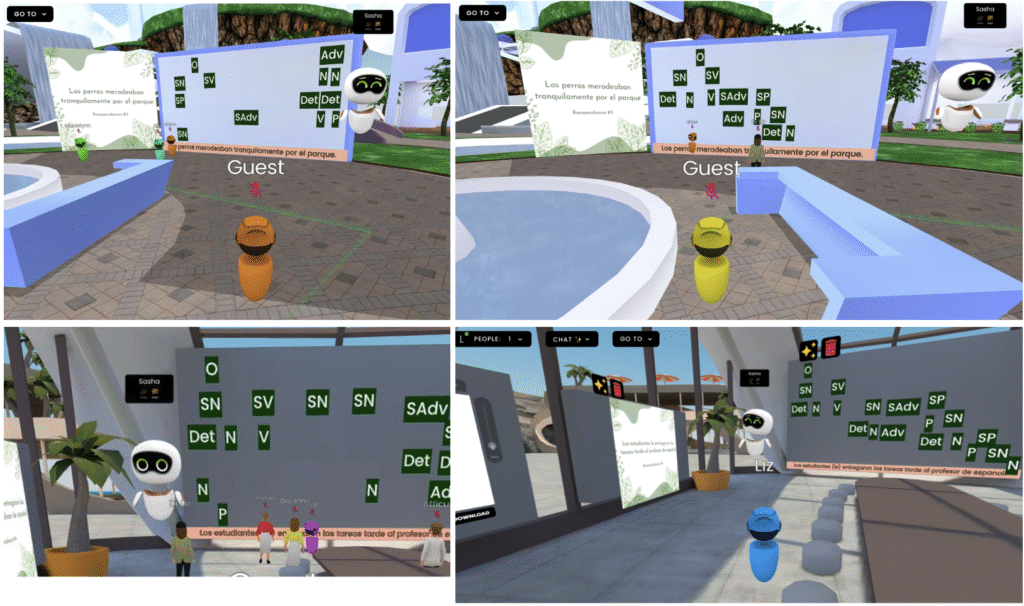

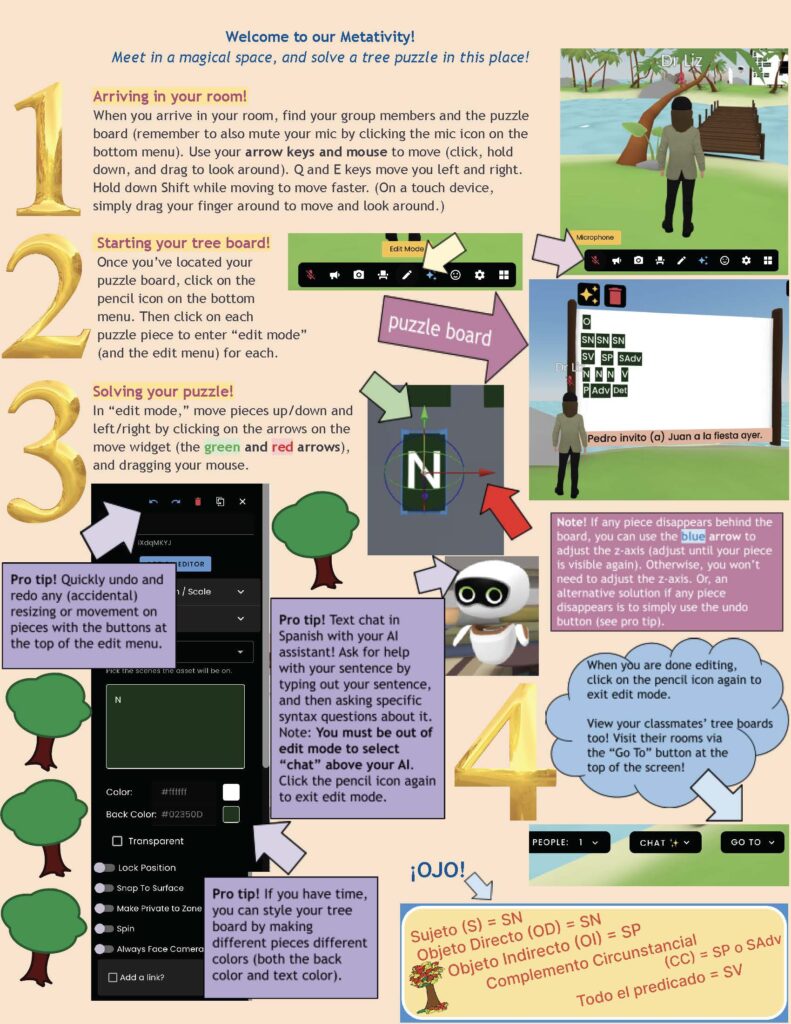

To set up each puzzle, I created “puzzle pieces” for each sentence and placed them on an in-world board in FrameVR. The puzzle pieces were text label assets I had added and labeled as SN, SV, etc. My students would then need to rearrange these pieces on the board to create the tree diagram for their assigned sentence. To move the pieces around, students used the move widget that appears on an asset when in edit mode (see the picture below). To enter edit mode, students clicked on the pencil icon in the menu at the bottom of the screen and then clicked on each puzzle piece. I specifically instructed them to use only the green and red arrows on the move widget, as these control the y-axis (up and down movement) and x-axis (left and right movement), respectively. This strategy would keep the puzzle pieces “on” the board, and it would also help the activity be more manageable for students skill-wise. To move each piece, students used their mouse to click on the red or green arrow and drag.

Into the Metaverse: From Demo Room to Puzzle Rooms

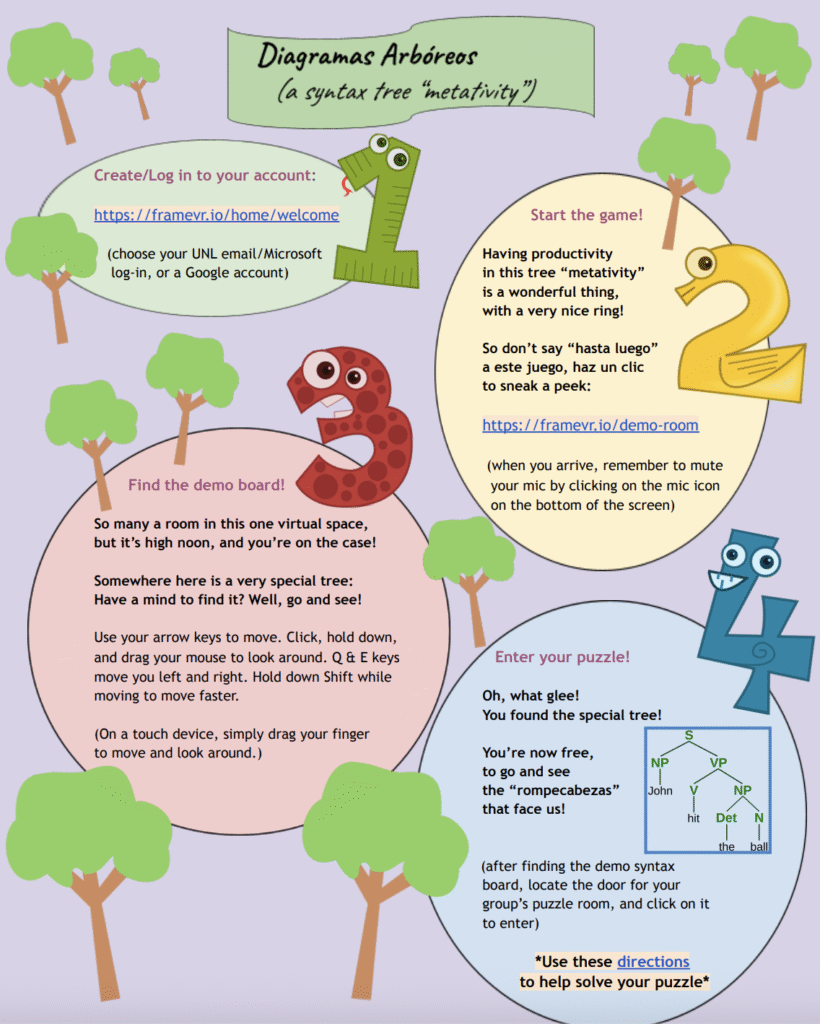

To help create a gamified environment for my metativity, I set up a path “into the metaverse” for my students, which would ultimately lead them to their group’s puzzle room. First, I provided an introductory sheet via a Google Doc (see a picture of it below). This sheet was a fun way for me to introduce my metativity via a poem.

The poem contained a link to a “demo room” I had set up for students. I chose the “Tropicana” environment for this room because it is spacious, with many different rooms within it along with an outside area. It was therefore perfect for facilitating a game-like atmosphere from the start, and for students to get acclimated to moving in the 3D space in their avatar form. Students had to go and find the demo puzzle I had created (which was in the outside area, away from the spawn point), and to then locate the correct door near it that would lead them to their group’s puzzle room (see a picture of the doors and demo puzzle below). The demo puzzle was the example (“modelo”) sentence from our worksheet, and I had “solved” the puzzle by arranging the pieces correctly on the board to represent the sentence’s structure (thereby mimicking the example tree on the worksheet). This served as a model of my expectations for how a completed tree board would look in Frame’s interface.

There were three doors (3D model assets I had added) with text labels on them indicating the sentence/puzzle number. Another text label that I created read “Click to enter!” on each door, and I added Frame room URLs to each of these labels (through the edit menu). When clicked, students were therefore taken to their group’s “puzzle room.” I chose three outdoor environments for these rooms (“Aeropolis” for puzzle #3, “Resort” for puzzle #4, and “Island” for puzzle #6), as these were open enough to accommodate a group working together, and the outdoors matched well with the theme of trees. Along with the puzzle boards, I also added a welcoming Canva sign (as an image asset) with the group’s sentence written on it, along with an interactive whiteboard that students could use for writing notes. Lastly, I added an embodied AI agent as well, whom I had trained with a document (a .docx file in Spanish) that contained relevant notes on syntactic structure and syntax trees. The agent was able to text chat in Spanish if students had questions about syntax as it related to their puzzles. See below for a picture of the setup in the “Aeropolis” room.

My students really enjoyed the metativity: some photos can be found below. They were all able to complete the task in the allotted time, and their puzzles were all solved correctly. Students also enjoyed the opportunity to collaborate in a different way, and found it relatively easy to move the puzzle pieces. They viewed the experience as interesting and a break from more routine types of activities. The only technical difficulty that we ran into was needing to finish a student’s browser update (the pencil icon was not working otherwise), which we corrected on the spot without further issues.

To help students complete the task, I also prepared a directions sheet for them on another Google Doc (see a picture of it below). It reminded students to mute their mics when in their puzzle room, and introduced them to the task and how to use the move widget. I also included some quick tips, such as where the “undo” and “redo” buttons are located and how to change puzzle piece colors if they wanted to (in the edit menu). I also directed their attention to the AI agent. Though we did not have time to explore these features in depth, students enjoyed learning about the capabilities of the software.

In fact, many of my students enjoyed the ability to customize their avatars, even though I had not included directions on how to change avatar settings. My students therefore found Frame’s interface both fun and intuitive. They enjoyed choosing between robot-type or human-type avatars and further customizing them (you can easily change or customize your avatar by clicking on the gear icon at the bottom of the screen, and then entering into user settings).

Finally, another unique feature of Frame is the “Go To” button at the top of the screen. This feature allows you to create direct links to other Frame rooms. Because my students would be submitting their completed syntax worksheet via our Canvas LMS at the end of the week, I used this function to set up links to all three puzzle rooms for the class. This was helpful, as students were then able to visit each group’s room after class to review the trees.

Seeing the Impact

Metativities can facilitate digitally inclusive and nontraditional ways of learning and engaging with class content, and ultimately, they can have a positive impact on students’ digital literacy development, too. For me, Frame filled a specific pedagogical need I had with respect to designing a collaborative and digital syntax tree activity, but the possibilities when it comes to creating metativities are vast. Moreover, and although it may take a little bit of time to initially set up, you can easily reuse your metativity from semester to semester (in my case, I just need to move my puzzle pieces back to their original setup on the board).

Reflecting more on my metativity, teachers can increase the difficulty level of this type of puzzle by creating a surplus of pieces, and then having students decide which ones to include in their specific tree. You could also exclude pieces on purpose and then ask students to fill in the missing ones (to do this, they could use the “duplicate” function in the edit menu to quickly duplicate an existing piece, and then relabel it appropriately). Alternatively, you could also create a version of this task where your students need to label your premade pieces on their own (using the edit menu) and then move them around to form the correct tree.

Various other metativities could also be designed for in-person classes, but they could also be designed for hybrid or online courses, especially since Frame is a 3D web conferencing software with both screen and webcam sharing capability in-world. In fact, in the July 2024 issue of The FLTMAG, I published an article about how I use Frame for hybrid office hours. Readers can therefore find detailed information there about how to get started with Frame, some of the software’s main features, and several ideas for using the platform in both face-to-face and online language courses. You can also check out Frame’s official blog to stay current with updates to the platform.

I also encourage educators to think about how a longer metativity could lend itself to project-based learning. Indeed, I have seen firsthand how a final project that focused on creating artwork (3D models) in immersive VR within a “makerspace” we created in the language lab resulted in a powerful experiential learning opportunity for students in a Russian Cultural Studies course focused on art (we published an article about our experience in the CALICO Journal). In fact, 3D models can be used in FrameVR for various purposes, such as to create a cultural art exhibit containing AI-generated 3D models.

With that in mind, I was therefore very excited when one of my students was so inspired by Frame’s capabilities that they decided to use the software for their final project in another Spanish course focusing on Mexican studies. This student chose an open world environment and placed a map (an image asset) on the floor and spread it out. They then added text area assets and arranged them throughout the map with various cultural notes written on them (see an animated walkthrough below). This is yet another example of how FrameVR could be utilized for project-based learning in the language classroom. You could even add narrations to this student’s project (through audio or video assets), which can then be placed throughout the map.

Interestingly, and thinking more about the metativity discussed in this article, the idea of creating “pieces,” and having students move them around on in-world boards, can be extended to other ideas for metativities in the language classroom as well. One such idea could be a version of magnetic poetry done in the target language. This is a hands-on task where students use pre-printed words or phrases on magnetic tiles to arrange, and rearrange, them in different ways to form unique poems. This can be done using text label assets in Frame, and it can facilitate creative expression in the target language, while also working to build vocabulary and grammatical understanding of sentence structure. Another idea would be to create an “escape room,” where students are placed in a themed room and must follow clues and solve puzzles within a time limit. They could move from station to station, either within one room or between several. Clues could also be easily marked using image assets, or you could train embodied AI agents in your room on specific materials, or give them further instructions on how to assist. Furthermore, you could add private voice zone assets beforehand to your room, so that small teams are able to communicate with only one another (without being heard by others outside the voice zone in the same room). You can design tasks that are similar to jigsaw puzzles or memory games (with the use of image and text label assets) for your escape room as well. Let the metaverse accommodate your creativity, and be sure to place your ideas for different types of metativities in the comments below!

References

Enkin, E. (2024). “Making it” in the language classroom: A look at 3D modeling with LumaAI. The FLTMAG (July 2024). https://fltmag.com/3d-modeling-luma-ai/

Enkin, E. (2024). Reframing office hours: Reimagining Mozilla Hubs in FrameVR. The FLTMAG (July 2024). https://fltmag.com/officehours-framevr/

Enkin, E., Tytarenko, O., & Kirschling, E. (2021). Integrating and assessing the use of a “Makerspace” in a Russian cultural studies course: Utilizing immersive virtual reality and 3D printing for project-based learning. CALICO Journal, 38(1), 103-127. https://doi.org/10.1558/cj.40926