Designing with Purpose: Pedagogical Reflections for the Development of AI Speaking Tools

By Christiane Reves, PhD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Language Program Director for German, Department of German, New York University, former Assistant Teaching Professor and Lower Division Coordinator German, School of International Letters and Cultures, Arizona State University and Mariana Bahtchevanova, PhD, Teaching Professor, Lower Division Coordinator, French, School of International Letters and Cultures, Arizona State University

DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.69732/JWJF8837

When we ask our language students where they practice speaking outside of class, the most common answer is simple: nowhere. While some learners have friends or family who speak the target language, most lack consistent opportunities for real-time conversations, and this problem is often even more acute for students learning language online, since they do not have as many opportunities to connect with their classmates as students in face-to-face courses do.

This is one reason why we prioritize interpersonal speaking during our weekly class sessions on Zoom. However, creating task oriented speaking opportunities in an online learning environment comes with a set of challenges. Students are often geographically dispersed, live in different time zones, and have varied personal and professional commitments. As a result, synchronous sessions that include speaking practice tend to be brief, and scheduling conflicts can limit both peer-to-peer and instructor-led interactions. Additionally, providing regular, timely, and individualized feedback to large groups of learners can be challenging even to the most dedicated instructors.

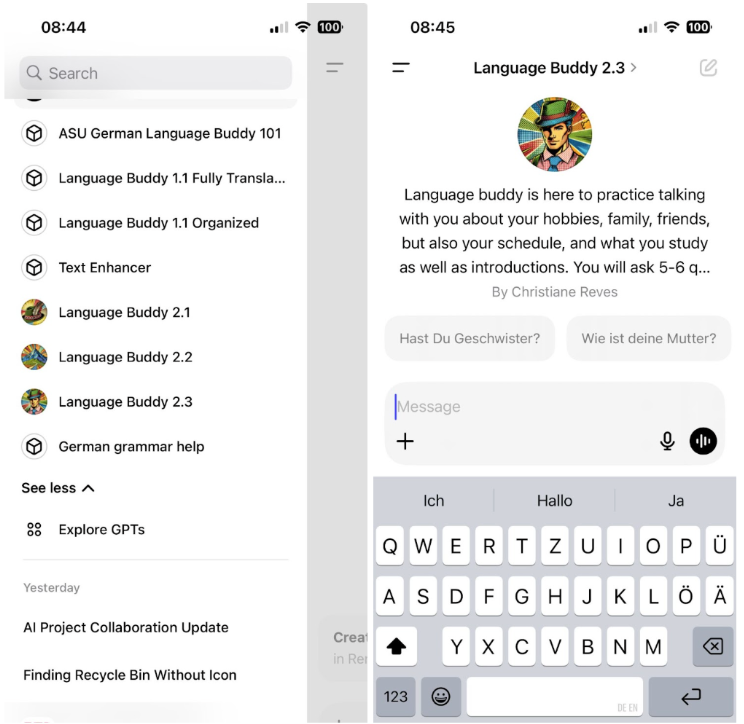

These realities became the foundation for an AI project for interpersonal speaking practice named “Language Buddy.” A proposal was submitted by the lower-division coordinator of the German program and was one of the projects selected in the first round of Arizona State University’s AI Innovation Challenge, following the university’s collaboration with OpenAI in January 2024. We started with the first pilot for German 101 online in summer 2024, and did two more iterations with improved versions in fall 2024. In the spring semester 2025 we also launched it for French 101 online as well as intermediate intensive French (FRE 210) in person. Each of the French and German online sections had between 30 and 60 students, and the French in-person course had around 15 students.

The objective was to design a tool that would be accessible 24/7, provide immediate standards-based feedback, foster learner motivation, and simulate interaction close to talking with a native speaker, while remaining calibrated to the learner’s current proficiency level and aligned with the course content, including its tasks, vocabulary, and grammar.

After initially establishing the functionality of AI for speaking practice, we created the “Language Buddy” custom GPT as an oral assignment. The tool was integrated into the course design and refined through multiple iterations between summer 2024 and 2025, drawing on feedback from both students and instructors to ensure alignment with pedagogical objectives and assessment standards.

As part of their course assignments, students completed three structured speaking tasks. The prompts focused on the following themes: greetings and introductions, classes and daily schedules, and family and personal life. After completing a guided setup—activating their ChatGPT EDU account, installing the ChatGPT mobile app, and accessing the tool on a mobile device—students participated in 4-5 minute conversations aligned with chapter content and communicative functions. The AI tool, trained with course materials and designed to operate within novice-level proficiency standards, provided brief, end-of-conversation feedback to support learner development. Its knowledge base was built around proficiency guidelines and included key vocabulary, grammatical structures, and communicative goals introduced in each unit. To reinforce pedagogical alignment, the custom GPT was also supplied with model interactions that reflected course-specific learning objectives and scaffolded interpersonal communication at the appropriate level. Students recorded their conversations using Zoom and submitted the video recording, transcript, and a short survey to reflect on their experience. They received full credit for completing the assignment, regardless of performance, with the goal of encouraging low-stakes practice and reducing speaking anxiety. This setup allowed instructors to efficiently review student performance and offered practical insights into the instructional use of Language Buddy. All instructions were embedded within the Canvas course structure.

We aimed for coherent outcomes and a positive user experience for both students and instructors by grounding the tool in key design and pedagogical principles: focusing on gains in oral proficiency and the development of communicative competence; aligning with proficiency standards and building a level-appropriate knowledge base; designing with the online learner in mind; maximizing functionality within the limitations of current AI technology; and anchoring the project in an ethical framework.

Focusing on Gains in Oral Proficiency and the Development of Communicative Competence

Speaking drives language proficiency, which is why this project began with one goal: to design a tool for oral practice. Research consistently shows that frequent, interactive speaking boosts fluency, vocabulary, and grammatical accuracy (Long, 1996) and is critical for progressing through proficiency levels. Distributed practice likewise promotes stronger long-term retention and performance in second language learning (Kakitani & Kormos, 2024). Speaking also strengthens memory consolidation and metalinguistic awareness through feedback and self-monitoring. Without regular opportunities, learners may build strong receptive skills yet still struggle in real-time communication. Studies further highlight the importance of negotiated interaction—clarification requests, confirmation checks, and other authentic exchanges—because they not only accelerate language acquisition but also improve retention (Long, 1996; Ellis, 2012).

The goal was not merely to develop linguistic competence—the accurate use of vocabulary and grammar—but to foster communicative competence, as defined by Canale and Swain (1980). Communicative competence encompasses a learner’s ability not only to produce correct sentences but also to use language meaningfully, appropriately, and effectively in context, aligning form with function and social norms. In practical terms, we aimed for a conversational agent that moved beyond static, form-based exchanges and instead replicated the dynamics of real-world interaction. This meant to train the tool to generate grammatically accurate responses while managing pragmatic functions such as greeting, clarifying misunderstandings, negotiating meaning, shifting topics, and closing conversations—all central to competent communicative behavior.

To support communicative competence, prompt engineering included opening salutations like “Hi, how’s it going?”; discourse markers and transitions for topic shifts (e.g., “By the way…” or “Speaking of that…”); repair strategies such as “Could you say that again?” or “What do you mean?”; and culturally appropriate leave-takings like “Talk to you later” or “Have a great day.” These were not merely linguistic choices but deliberate representations of authentic interactive norms, ensuring learners practiced real communication, not just isolated language forms.

In sum, the tool was designed to support both linguistic accuracy and communicative competence, recognizing that effective speaking practice depends not only on structured output but also on context-rich, meaningful interaction that mirrors real-world communication.

Aligning with Proficiency Guidelines and Building a Level-Appropriate Knowledge Base

Grounding the AI tool in a language proficiency framework was essential for supporting language development. The tool was designed for the needs of Novice-level language learners, as defined by the ACTFL Proficiency Guidelines – Speaking (ACTFL, 2024). At this stage, learners typically produce short, formulaic phrases, use high-frequency vocabulary, and respond to familiar topics. By aligning the custom GPT’s language generation with these descriptors, we wanted to ensure that learners engaged with input matched to their proficiency level.

Our goal was to constrain the AI tool to produce language that was accessible and supportive, avoiding overly complex input that might overwhelm students. This decision drew on the comprehensible input hypothesis, which holds that learners progress most effectively when exposed to language just slightly above their current proficiency level (Krashen, 1982). Input far beyond a learner’s ability can cause frustration and anxiety, reducing both acquisition and retention (Xu & Xie, 2024). In contrast, language grounded in established proficiency benchmarks promotes cognitive ease, builds confidence, and supports sustained engagement.

To reach level-appropriate interaction, we built a custom knowledge base drawn from core course materials: chapter learning outcomes, thematic vocabulary lists, grammar explanations, and topic-specific conversation transcripts. We also embedded the ACTFL Novice-level speaking guidelines to keep the tool aligned with our pedagogical objectives. By intentionally matching the AI tool’s output to learners’ current proficiency level, we tried to create a supportive environment where students could practice with confidence, focus on building skills step-by-step, and stay motivated to engage in sustained language learning.

Designing with the Online Learner in Mind

Online language learners face unique challenges that limit meaningful interpersonal speaking practice. Many of our students are enrolled in accelerated 7.5-week courses while juggling professional, academic, and family responsibilities across multiple time zones. Scheduling conflicts further reduce opportunities for real-time interaction.

Current solutions—such as asynchronous video recordings with delayed responses—lack the immediacy and dynamics of live conversations. Outsourcing practice to paid platforms with native speakers can provide interaction but often lacks pedagogical alignment, overwhelming novice learners. Some of the paid platforms can be expensive and have a limited number of languages and interaction sessions. Synchronous instructor-led online meetings are effective but limited in availability; peer online sessions offer more flexibility but lack supervision and require lengthy post-session reviews.

In contrast, an AI-powered speaking tool can be integrated directly with course content, enabling guided, level-appropriate conversations available any time and at any length. It can offer a safe, judgment-free environment through the anonymity of AI, immediate constructive feedback, and the option to control the pace and content. Gains in pronunciation and interaction confidence can, in turn, increase motivation (Choi, 2025). For instructors, such tools provide quick performance insights without hours of recording review so that they can focus more on tailored in-depth feedback.

A Duolingo study found that learners using AI-based video calls twice daily for a month achieved greater speaking proficiency gains than those completing only app-based lessons (Kittredge, Lee, & Jiang, 2025). In our own classes, we observed that students using Language Buddy tended to spend more time speaking than expected and reported greater confidence in managing basic interactions—suggesting that the tool can help bridge the gap between classroom instruction and spontaneous language use. These observations highlight the value of AI-driven speaking tools for online learners—offering unlimited, structured, scalable, and pedagogically aligned practice where traditional tools fall short.

Maximizing Functionality Within the Limitations of Current AI Technology

AI tools can serve as tireless speaking partners, but their effectiveness in language learning depends on how their output is designed and constrained. We encountered issues also noted in recent studies: the model sometimes switched to a different language, produced grammatical structures too complex for novice learners, paused unpredictably, went off-topic, or delivered overly technical or inaccurate corrections. At times, it also failed to align with task prompts. Large language models also tend to over-accommodate user input and may drift from instructional goals unless carefully guided. To address these tendencies, we set design guardrails: the bot must remain in the target language, create short responses, limit each session to a manageable number of turns, and provide as feedback no more than two corrections and one suggestion at the end. These constraints helped improve consistency, but they did not eliminate all challenges.

Another limitation was related to content and cultural embeddedness: while scalable and tireless, AI lacks true communicative intent and may not always reflect pragmatic or cultural authenticity (Godwin-Jones, 2024). Responses can feel semantically flat, and AI feedback often lacks the personal encouragement that human instructors bring—critical for building confidence at early stages. Without integration into an instructor-led course, there is also a risk of learners over-relying on AI.

Recognizing these constraints, we shifted focus to training students. The majority had never spoken with AI in a foreign language and came with varied expectations. We provided clear instructions on technical setup, guidance for sustaining and restarting conversations, and reassurance that imperfect interactions were both normal and valuable. The exercise was framed as simulating unpredictable, real-world conversation, with the goal of building fluency through practice rather than achieving perfect performance. Students were encouraged to practice for 20–25 minutes before submitting their recorded conversation.

Below you can see some sample student instructions that we distributed to students in advance of their first conversation with Language Buddy.

| Sample Student Instructions:

Language Buddy Pilot Conversation 1 Important: Before recording your conversation, be sure that you have spent at least 20–30 minutes practicing in several conversations with Language Buddy so that you’re comfortable and familiar with the tool. It is ok if a conversation does not go perfectly. You can start over anytime. Assignment OverviewWelcome to your first ‘official’ Language Buddy Conversation of the pilot!

Need HELP?

Helpful Phrases: Langsamer bitte – slower please Tips for SuccessThink of it as meeting a stranger in Germany who assumes you understand German. Use the opportunity to practice asking for clarification and adjusting the flow to suit your learning needs. It’s not easy, but the more often you practice, and the more German you add each week to your register, the easier and more engaging it will get. Have fun! |

In sum, AI’s scalability, responsiveness, and availability make it a compelling addition to speaking practice. Yet these strengths are matched by limitations: without pedagogical guardrails, cultural integration, and student preparation, AI can drift off-task, overwhelm, or frustrate learners. Its effectiveness rests not only on its capabilities, but on how those capabilities are constrained, guided, and embedded within a coherent instructional framework.

Anchoring the Project in an Ethical Framework

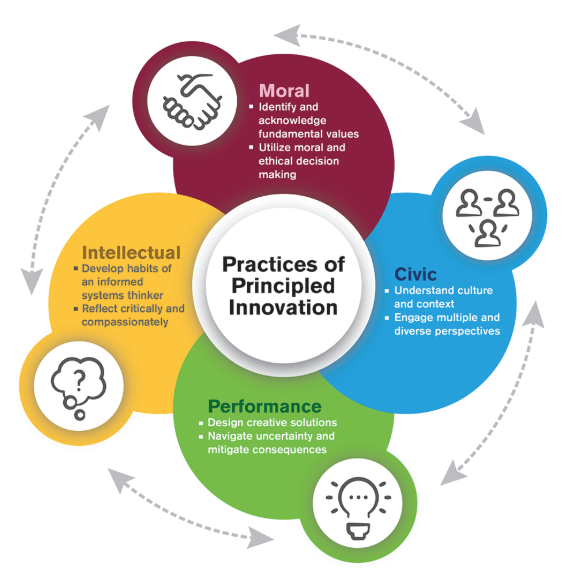

The use of AI in education, particularly in language learning, introduces complex ethical considerations that go beyond technical performance. As we developed an AI-powered speaking tool, it became clear that an ethical framework was essential to guide decision-making around learner privacy, agency, access, and well-being. Arizona State University’s Principled Innovation (PI) Framework (Arizona State University, 2025) provided the foundation for this work, offering a four-domain compass—moral, civic, intellectual, and performance—to ensure that the project advanced human flourishing and remained grounded in pedagogical intent.

Each domain shaped the tool’s development. The moral dimension led to design choices like protecting student data. The civic dimension encouraged us to design culturally respectful AI personas that would feel appropriate and relatable for our learners. Rather than relying on exaggerated or stereotypical traits, we created simple, student-centered identities. These personas were close to the life experiences of our learners, which helped foster a sense of peer-to-peer interaction. We kept the cultural framing subtle allowing for the inclusion of additional personal details (e.g., hobbies or interests) when relevant to the conversation. While the cultural framing was limited in the early versions of ChatGPT, and the outcomes in terms of authentic cultural nuance were minimal, the effort reflected an initial step toward more inclusive and humanized AI design. As newer versions of ChatGPT that include Advanced Voice Mode are available, there seems to be greater potential for conveying cultural and interpersonal nuances. This remains an active area of development for future iterations of AI tools for speaking practice. The intellectual domain of the framework led us to transparent documentation of prompt revisions, while the performance dimension required that success be measured by alignment with proficiency goals.

Ultimately, the Principled Innovation Framework ensured that ethical considerations were embedded at every stage of development—guiding the tool toward equitable, responsible, and learner-centered design.

Suggestions for Developing Your Own AI Tool

If you’re thinking about building an AI tool to support your language learners, it helps to start small, keep it focused, and make sure every choice ties back to clear learning goals. Here are a few suggestions:

- Start with one, well-scaffolded conversation scenario

Pick a familiar, purposeful topic—like daily routines or weekend plans—and anchor it in specific language outcomes. In the system prompt, use level-specific descriptors instead of vague instructions like “simplify the language.” Add target-language repair phrases so learners can pause or ask for clarification without breaking the flow. Keep the number of turns manageable so the practice stays focused and recordings are easy to review. - Train both the bot and your learners

Give the custom GPT your own course materials—vocabulary lists, grammar points, sample dialogues—so its output fits your teaching. Let students know what to expect, walk them through setup, and share strategies for keeping the conversation going. Remind them that “imperfect” conversations are part of the learning process and that the goal is proficiency, not perfection. - Reduce barriers and make it easy to use

If possible, connect the tool directly to your own Learning Management System so students can jump right in. Keep a running log of prompt changes and the thinking behind them—it’s great for tracking what works, what doesn’t, and why. - Keep culture front and center

Shape prompts around real-world tasks and pragmatic norms, so learners get language in context. And if you can, add visuals, avatars, or immersive role-play elements to make the experience more engaging and authentic. - Stay flexible and keep iterating

AI changes fast—what’s tricky today might be easy tomorrow. Keep refining your prompts, and check that the tool stays grounded in pedagogy, ethical use, and cultural relevance.

With the right focus, AI can open new doors for language learning—supporting proficiency, confidence, and authentic interaction. Keep experimenting, keep improving, and let curiosity drive the next breakthrough.

Conclusion

AI-powered speaking tools can extend language learning well beyond the classroom, giving learners low-stakes, individualized practice that fosters fluency, provides immediate, level-appropriate feedback, and builds confidence in real-time interaction. When integrated into a course, they can ensure more consistent speaking engagement, enable targeted formative assessment, and support greater differentiation—particularly in large-scale or asynchronous environments. This can free instructors to focus on personalized coaching, nuanced feedback, and culturally rich content, amplifying instructional impact.

AI should be seen as a complement, not a substitute, for expert instruction—one that expands opportunities for sustained, focused speaking practice while keeping the human connection at the heart of language learning. For educators exploring similar initiatives, the key is to let instructional goals lead, start small, iterate often, and keep both learners and instructors in mind. When thoughtfully implemented within a pedagogical framework, AI has the potential to become a powerful ally in helping students develop the confidence, fluency, and cultural awareness needed to communicate in a foreign language.

References

ACTFL. (2024). Proficiency guidelines–Speaking. American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages.

Arizona State University. (2025). Principled innovation: One-pager overview. https://pi.education.asu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/pi-one-pager-2025.pdf

Canale, M., & Swain, M. (1980). Theoretical bases of communicative approaches. Applied Linguistics, 1(1), 1–47.

Choi, W. (2025). The role of changes in pronunciation ability and anxiety through Gen-AI on EFL learners’ self-directed speaking motivation and social interaction confidence: A CHAT perspective. System, 133, 103788. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2025.103788

Ellis, R. (2012). Language teaching research and language pedagogy. Wiley Blackwell.

Godwin-Jones, R. (2024, October 18). Generative AI, pragmatics, and authenticity in second language learning [Preprint]. arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2410.14395

Kakitani, J., & Kormos, J. (2024). The effects of distributed practice on second language fluency development. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 46(3), 770–794. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0272263124000251

Kittredge, A., Lee, C., & Jiang, X. (2025, June 24). Video call improves Japanese English learners’ speaking skills (Duolingo Research Report DRR-25-06). Duolingo. https://www.duolingo.com/efficacy

Krashen, S. D. (1982). Principles and practice in second language acquisition. Pergamon.

Long, M. H. (1996). The role of the linguistic environment in second language acquisition. In W. C. Ritchie & T. K. Bhatia (Eds.), Handbook of second language acquisition (pp. 413–468). Academic Press.

Xu, Y., & Xie, Z. (2024). Exploring the predictors of foreign language anxiety: The roles of language proficiency, language exposure, and cognitive control. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 15, Article 1492701. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1492701

Oh, bThis is really fascinating! AI language tools have the potential to revolutionize speaking practice, particularly for online learners. I’m interested to watch how Language Buddy develops further and affects language instruction.

This is super interesting! AI language tools could be a game-changer for practicing speaking, especially for online learners. I’m curious to see how Language Buddy continues to evolve and impact language education.

Purposeful design in developing AI-speaking tools is not just about technology, but about creating real value for users.

Great article! It’s inspiring to see AI used to enhance language learning with tools like “Language Buddy.” I especially appreciate the focus on aligning technology with real classroom needs.