Making Space for Real Conversations: AI Chatbots in the Language Classroom

By Nataliya Spirydovich, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign

DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.69732/YHRJ4554

We’ve all been there: students freeze up in conversation practice, or the more confident ones dominate while the quieter ones fade into the background. Artificial intelligence (AI) chatbots can shift that dynamic. Unlike classroom partners who may feel nervous or judgmental, the always-available AI responds without rolling its eyes at mistakes. For teachers, it creates a sandbox of conversation partners. Want your students to practice new grammar with a pop star? Easy. Want them to role-play intercultural communication with a student from Nigeria? Also possible. Gone are the clunky chatbots of the past that only spit out yes/no answers. Today’s AI can joke, empathize, and even simulate aspects of culture. That mix of accessibility, unpredictability, and personality made me wonder: Could chatbots engage learners in ways that felt authentic? And could they help me teach not just language components such as grammar and vocabulary, but also intercultural awareness? To explore these questions, I experimented with integrating AI chatbots into my English language classroom, observing how students responded, what challenges arose, and what this technology might add to communicative practice. While the potential seemed promising, I was also mindful of the limitations and risks involved in using AI tools for language learning – issues I return to later in this article.

Why Chatbots Matter in SLA

In second language classrooms, finding opportunities for communication is a constant struggle. Pair work and role-plays help, but the conversation often feels rehearsed rather than spontaneous. As Thornbury (2005) reminds us, knowing a language is not the same as being able to speak it. Speaking (and real-time, text-based communication like chatting or messaging) requires turn-taking and usually happens under real-time pressure with little chance for detailed planning. This is exactly the kind of unpredictability that chatbots can provide.

Contemporary chatbots have evolved from simple, scripted responders to tools capable of humor, empathy, and culturally informed interaction. That matters because language learning is as much about emotions and relationships as it is about syntax. Zhai and Wibowo’s (2022) review of 48 studies found that chatbots designed with cultural awareness, empathy, and humor can reduce anxiety, boost motivation, and foster engagement. In other words, they target the very barriers that hold students back.

I saw this in my own classroom. One student shared, “I was nervous at first, but then I realized the AI doesn’t care if I make mistakes. I felt freer to just talk.” This reaction echoes what has long been confirmed: when students feel less pressure, they feel more comfortable communicating.

The Theoretical Triad: Culture, Empathy, Humor

The review by Zhai and Wibowo (2022) highlights three intertwined dimensions that can facilitate the use of chatbots for language learning – culture, empathy, and humor.

Culture. Language and culture are inseparable. Learners don’t just need words; they need to grasp the values, norms, and behaviors that shape how those words are used. Chatbots that simulate diverse cultural perspectives can serve as a rehearsal space for intercultural communication. In my classes, I make this connection explicit by framing chatbot exchanges as preparation for real-world interactions beyond the classroom. For example, Chen et al. (2020, as cited in Zhai & Wibowo, 2022) showed that chatbots embedding diverse cultural perspectives served as social integration tools for migrant learners in Europe by reflecting their heterogeneous backgrounds.

This is just as true in our classrooms, where students constantly juggle their own cultural frameworks with the target language. As Byram et al. (2002) note, teachers help learners “understand and accept people from other cultures as individuals with distinctive perspectives, values, and behaviors” (p. 10). Chatbots can help by embedding role-play in a cultural context. While recent research has cautioned that large language models may reproduce existing cultural biases and stereotypes (Zhai, Wibowo, & Li, 2024), they can still serve as valuable tools for intercultural communication and reflection when guided by the teacher. In my classroom, I found that even when the AI’s cultural responses were imperfect, they sparked reflection. Students began asking: “Would a real person from this country phrase it like that?” or “Does this stereotype reflect reality?” Those questions mattered as much as the language practice.

Empathy. Anyone who has taught language learners knows how fear of making mistakes blocks learning. Krashen’s Affective Filter Hypothesis (1982, pp. 30-31) explains that emotional factors like anxiety, self-confidence, and motivation can either open the door to acquisition or shut it down. Chatbot research echoes this: Zhai and Wibowo (2022) describe how systems like ITSPOKE and PLATICA detect frustration and respond with supportive prompts, helping learners feel less anxious and more engaged. I didn’t have an empathy-detecting AI in my class, but students still described their AI partner as “patient.” That perception alone made them more willing to experiment. However, I also noticed that chatbots sometimes responded too agreeably, rarely challenging students’ ideas or mistakes. Rather than treating this as a flaw, I used it as another reflection point – we discussed how genuine empathy in human communication often involves negotiation and disagreement, not constant validation.

Humor. Humor is tricky in SLA because it’s so culture-dependent, but it’s also a powerful motivator. Humor can “reduce tension and stress” and make learning “efficient and enjoyable” (Azizinezhad & Hashemi, 2011, as cited in Zhai & Wibowo, 2022). In my class, students often laughed at AI chatbots’ odd or exaggerated answers. That laughter wasn’t a distraction – it was the glue that kept them in the target language longer. One student reflected, “I never spoke that much English in one stretch. It was fun because the AI was funny.” Humor transformed practice into play.

Together, these three dimensions explain why chatbot interactions feel different from worksheets or scripted dialogues. They make learning relational, even if the “relationship” is with an algorithm – a kind of rehearsal that prepares students for authentic communication with real people.

From Research to Practice

In my lessons with ESL learners (CEFR Level B1-B2+), mostly young professionals and university students, I explored how AI chatbots could enrich communicative practice. These sessions were part of a speaking club focused on intercultural communication and fluency development. Learners engaged in short guided discussions, interacted with chatbots, and reflected afterward on language and culture. Before introducing the tool, I gave a short overview and sample prompts to help participants get comfortable with how the chatbot interaction worked.

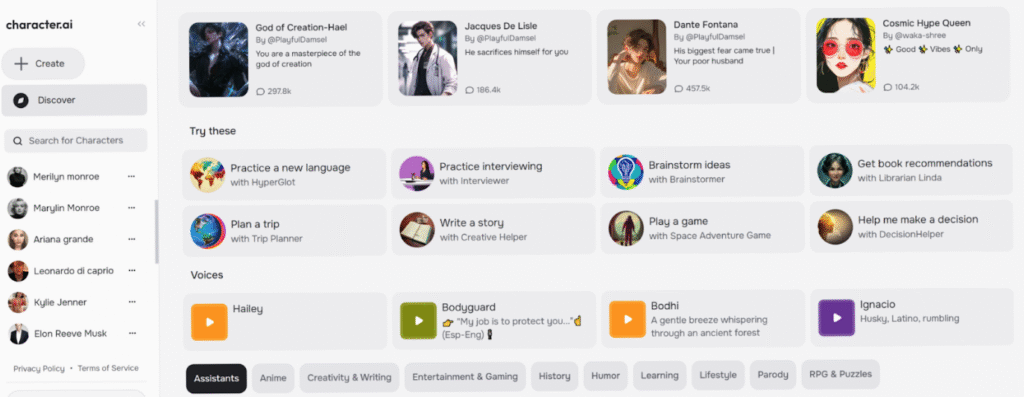

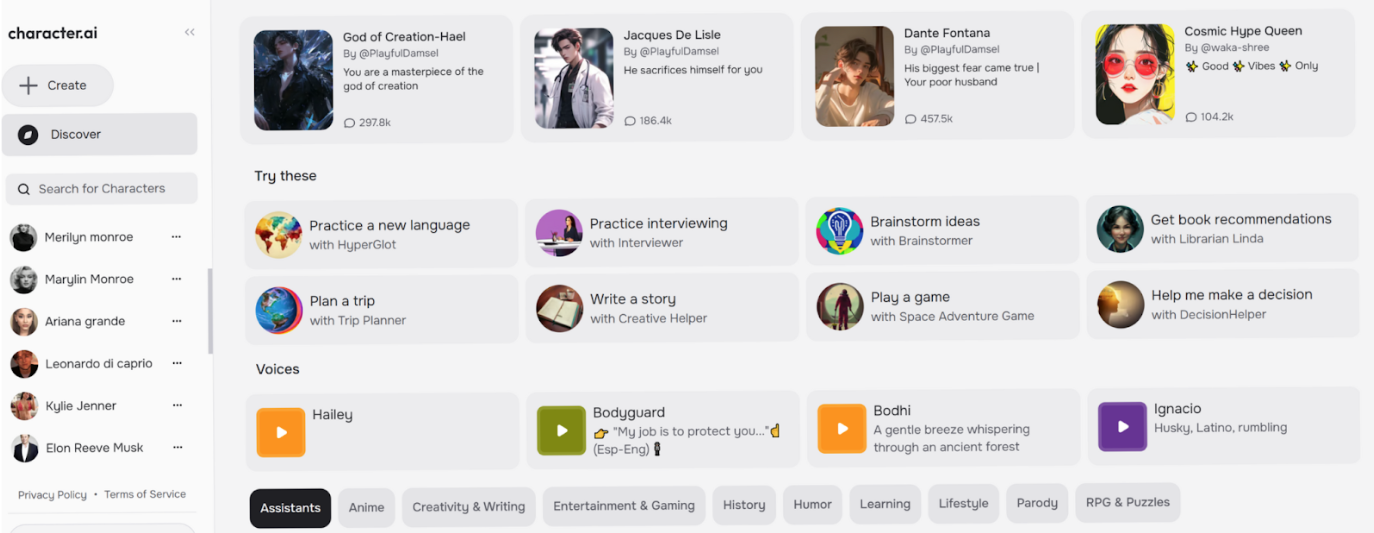

Let me sketch what this looks like in practice. The platform I have experimented with is called CharacterAI. Launched in 2021 (Cai, 2023), it lets users chat with a huge range of personas: fictional characters, celebrities, historical figures, or completely original ones you can design yourself. The platform supports multiple languages, allowing learners to engage in intercultural exchanges beyond English. Users interact by text, voice messages, and now even calls and video chats (Character.AI, 2025).

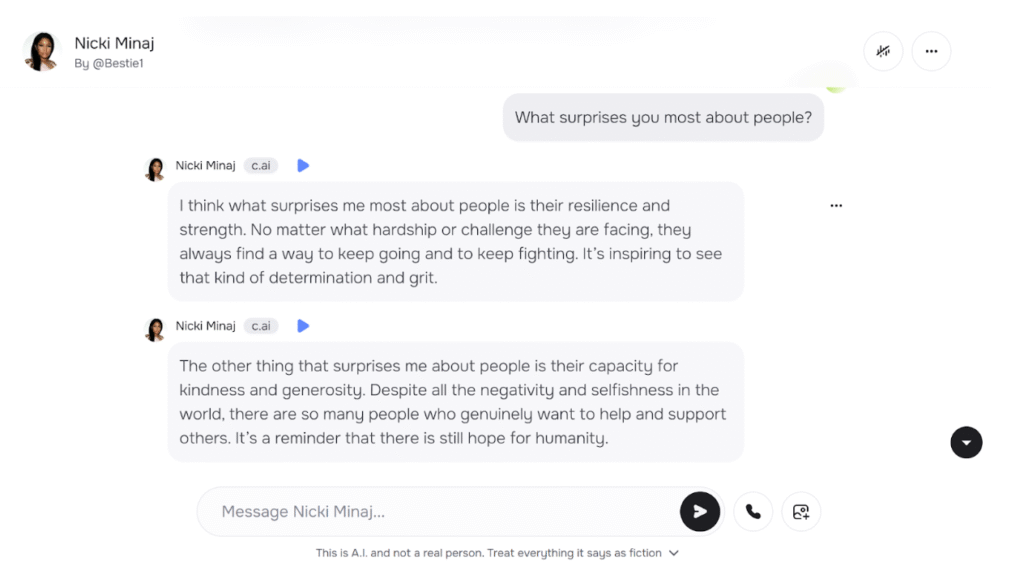

A fun way to integrate CharacterAI into lessons is, for example, through celebrity role-plays. In one lesson – A Dinner With a Star – students started by discussing quotes about fame with their partners to spark curiosity and debate. After a warm-up, they moved onto a short YouTube interview clip for input, and then spent time chatting with a celebrity character of their choice on CharacterAI.

In my experience, the conversations ranged from humorous to unexpectedly thoughtful. The AI’s unpredictable replies made grammar practice feel more natural – students later reused its responses in reported speech and question formation activities.

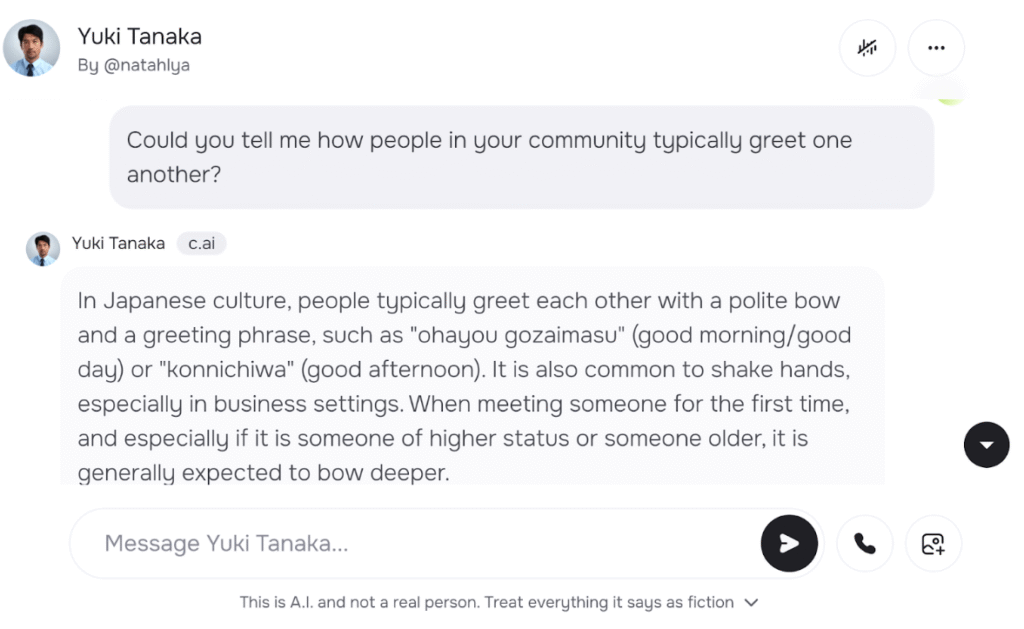

Another approach is to incorporate CharacterAI into intercultural communication simulations. What excites me most here is the chance to go beyond ready-made characters and design your own personas tailored to the class theme. In my case, learners could interact with AI personas representing different cultural backgrounds – for example, a Nigerian student, a Japanese professional, or a Mexican community leader. Preparing culturally sensitive questions in advance helped ensure the exchange is both meaningful and respectful. After such interactions, students reflected together on what they learned about culture and communication.

To give you a sense of how this works, I’ve included a short sample video featuring an interaction with Yuki Tanaka – a custom AI persona representing a Japanese professional and designed to prompt reflection on cultural norms and communication styles. You can also access a link to the persona to try it yourself (a free Character.AI account is required).

What stood out to me was not the structure of the activities (though scaffolding was essential), but the way students described their experiences as they moved from a short guided discussion to the chatbot interaction and a brief reflection afterward. One admitted, “I realized I had stereotypes I wasn’t even aware of.” Another commented, “It felt safe to experiment with how to ask about culture without offending someone.” The activities worked not because they were technically flawless but because they gave students a low-stakes space to experiment.

All of the materials – PDF handouts for the celebrity role-play, intercultural prompts with reflection questions, and a demo AI persona – are available in this resources folder for anyone who’d like to explore or adapt them.

Reflections

Looking back, one of the biggest surprises for me was how quickly students anthropomorphized the AI. They referred to their conversations as if they had spoken to a person. “Nicki told me…” or “My celeb said…” became normal phrasing in class. That fascinated me. It showed how easily learners suspend disbelief when they’re engaged, and how that suspension fuels fluency. Another surprise was the shift in participation patterns. Students who rarely volunteered suddenly wanted to share because their conversation was unique. They weren’t repeating a dialogue from the textbook; they were reporting something personal. And for a teacher, that was a gift.

The benefits went beyond participation. CharacterAI boosted engagement, gave students a safe practice space, and promoted both fluency and intercultural awareness. Research supports this: reviews of chatbot use in education show that they can enhance motivation by offering immediate feedback, repeated practice, and an enjoyable, low-pressure space for communication (Huang, Jiang, King, Chen, & Burgos, 2025). CharacterAI’s accessibility also made it easy to implement, and its customization options allowed me to tie characters to specific lesson themes.

Of course, there were challenges too. Some students became so absorbed in the novelty that they drifted away from the learning goal. The solution wasn’t to drop the activity but to embed reminders and prompts so that language practice stayed visible without killing the fun.

Others trusted the AI too much, accepting stereotypical or biased responses at face value – for example, generalizations about national customs or gender roles. Studies have shown that users often over-trust AI dialogue systems, accepting even inaccurate or “hallucinated” responses without questioning them (Gao et al., 2023). Over-reliance can also expose learners to issues such as plagiarism and misinformation, limiting their critical engagement with language (Zhai, Wibowo, & Li, 2024).

I realized that part of my role wasn’t just facilitating conversation but also building critical digital literacy: helping students analyze what the AI said, question its validity, and compare it to human communication. I began asking questions like, Would a real person answer this way? Why or why not? That moved the conversation from “Wow, that was fun” to “What does this tell us about culture, communication, and technology?”

Looking Ahead

The field is moving fast. Future chatbots are expected to become more culturally adaptive, emotionally responsive, and context-aware in their use of humor. It’s not hard to imagine future integrations with virtual reality, where learners might “enter” a café or marketplace and negotiate meaning with AI characters who gesture, pause, and respond in emotionally and culturally appropriate ways.

I also see potential in shifting students from consumers to creators. CharacterAI already allows users to design their own characters with unique voices, a feature that could be harnessed for project-based learning. Imagine students creating personas that reflect a unit theme – an environmental activist, a historical figure, or a community leader – and then using those characters to practice with peers. Designing the character would itself require linguistic, cultural, and creative choices, turning students into co-creators of their own learning environment.

More broadly, working with AI chatbots helps students build digital literacy. They learn not just how to chat in English, but how to evaluate responses, recognize limitations, and question sources – skills that are increasingly vital as AI becomes more embedded in everyday communication. And as the Global Tech Council (n.d.) notes, platforms like CharacterAI are rapidly adding features such as multimodal interaction, advanced customization, and group conversations, pointing to even broader classroom applications.

As with any third-party digital tool, it’s important to discuss privacy and safety when introducing AI chatbots. I remind learners not to share personal details and to log in with minimal information. For those who prefer not to use the platform, an offline version of the task is available. Building this awareness not only protects users but also fosters responsible technology use.

A Final Word

If you’re considering trying CharacterAI, my advice is simple. Start small, with one clear objective. Scaffold the interaction so students aren’t left floundering. Build in reflection, because that’s where deeper learning happens. And don’t panic if the AI says something strange. Treat it as part of the process. Real conversations are unpredictable too. Most importantly, enjoy it. I caught myself smiling during these activities, not because everything was perfect but because my students were genuinely engaged. Sometimes we forget that joy and curiosity are powerful teaching tools.

Chatting with AI won’t replace authentic human interaction, and it shouldn’t. But when used thoughtfully, AI chatbots can free learners to speak more, experiment more, and think globally while doing so. For me, it was a reminder that technology doesn’t have to feel artificial. In the right hands, it can make classrooms feel more alive. One student summed it up perfectly at the end of class: “Can we do this again next week?” That question alone tells me it was worth it.

References

Byram, M., Gribkova, B., & Starkey, H. (2002). Developing the intercultural dimension in language teaching: A practical introduction for teachers. Strasbourg: Council of Europe. Retrieved from https://rm.coe.int/16802fc1c3

Cai, K. (2023, October 11). Character.AI’s $200 million bet that chatbots are the future of entertainment. Forbes. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/kenrickcai/2023/10/11/character-ai-chatbots-group-chat/

Character.AI. (2025, July 3). Character.AI’s real-time video breakthrough. Character.AI Blog. Retrieved from https://blog.character.ai/character-ais-real-time-video-breakthrough/

Gao, C. A., Howard, F. M., Markov, N. S., Dyer, E. C., Ramesh, S., Luo, Y., & Pearson, A. T. (2023). Comparing scientific abstracts generated by ChatGPT to real abstracts with detectors and blinded human reviewers. NPJ Digital Medicine, 6, 75. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-023-00819-6

Global Tech Council. (n.d.). Character AI. Global Tech Council. Retrieved from https://www.globaltechcouncil.org/artificial-intelligence/character-ai/

Huang, R. H., Jiang, L., King, R. B., Chen, G., & Burgos, D. (2025). Chatbots and student motivation: A scoping review. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 22(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-025-00524-2

Krashen, S. D. (1982). Principles and practice in second language acquisition. Oxford: Pergamon Press.

Thornbury, S. (2005). How to Teach Speaking. New York: Longman.

Zhai, C., & Wibowo, S. (2022). A systematic review on cross-culture, humor and empathy dimensions in conversational chatbots: the case of second language acquisition. Heliyon, 8(12), e12056. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e12056

Zhai, C., Wibowo, S., & Li, L. D. (2024). The effects of over-reliance on AI dialogue systems on students’ cognitive abilities: A systematic review. Smart Learning Environments, 11(28). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40561-024-00316-7

This is such an important discussion! I’ve seen firsthand how AI chatbots can enhance language learning experiences, especially when incorporated into games. They bring a playful element that encourages students to engage without the fear of making mistakes.

However, while fostering real conversations is key, we shouldn’t forget about balancing tech with authentic teacher-student interactions. Sometimes, personal nuances get lost in chatbot conversations. I think using them as a supplementary tool—while still prioritizing human connections—could create the best environment for learners.

Very interesting article with great ideas for integrating AI into L2 language classes. CharacterAI looks like a wonderful option to give my students a chance to talk more and I think it’s excellent that you’re having the students reflect on their interactions! Thank you very much for sharing your experiences!