Games, Fun, and Learning: An Educational Escape Room on Campus

By Seyed Abdollah Shahrokni, Center for Teaching and Learning (CTL), Western Oregon University

DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.69732/UELJ6593

Immersed in the challenge, five players buzz with anticipation, their eyes gleaming with excitement as they explore every corner and detail of the carefully-designed space. They have tackled challenge after challenge, their hearts and minds set on finding the answers, but one puzzle continues to elude them. Focused and driven, they search tirelessly for the missing piece. What is it that they are not seeing? They have meticulously inspected all the books on the shelf, shone the UV flashlight on all surfaces, reassessed all the other previously-solved puzzles, looking for a clue, but none exists. Suddenly, a message crackles through the Zoom connection in the room, sparking a glimmer of hope. “Let’s take a moment to appreciate the power of recycling,” the clue reads, echoing through the room. With an “aha moment” shared among them, the players rush towards the recycle bin tucked in the corner. Digging through its contents, they unearth a strip of photos, each piece marked with a number. With triumphant cheers, they piece together the final combination and unlock the sealed box. Laughter and celebration fill the room.

– Author’s observation of the gameplay of “The Case of X” developed by Jerielle Cartales, Faculty of Criminal Justice Sciences, Western Oregon University.

Educational Escape Rooms (EER)

Educational escape rooms (EER) are a form of game-based learning (GBL; Grand-de-Prado et al, 2020, see Shahrokni, 2024, for an overview of GBL vs. Gamification), wherein participants collaborate to engage with subject matter and/or competencies by tackling various puzzle tasks, which typically follow a linear progression, each leading to the next, with a specific learning objective to achieve within a set time frame. The essence of an EER lies in immersing participants in a simulated scenario that requires resolution, serving as an educational tool aimed at guiding learners toward achieving specific learning outcomes through a game-based design. Educators can incorporate escape games into classrooms using various resources, including simple puzzle boxes or digital platforms such as Breakout EDU, Room Escape Maker, or Google Slides (see Huang, 2023, for an overview of digital educational escape rooms in language classrooms).

Research suggests numerous advantages for participants when playing EERs, mainly due to their emphasis on group problem-solving and focused disciplinary skills/content. These benefits encompass enhanced creativity and immediate feedback (Grand-de-Prado et al., 2020), fostering students’ sense of ownership and agency in their learning process (Veldkamp et al., 2020), and facilitating the participation of students who might otherwise be hesitant or reserved in traditional classroom tasks (Nicholson, 2015; Martens & Crawford, 2019), with equal appeal across genders (Lopez-Pernas et al., 2019; Nicholson, 2015). Even students who typically struggle in conventional classroom settings seem to exhibit deep engagement with EERs, which support Dilek and Dilek’s (2018) assertion that such experiences correspond with “memorable” or “extraordinary experiences” (p. 497). The observation at the beginning of this article also supports the idea of memorable experiences among students playing an EER.

Starting An EER on Campus

To take advantage of these benefits, we started an EER on our campus. This article delves into the development of this endeavor, covering the two key areas of logistics and game design, offering insights into developing EERs in classrooms and/or institutions. Further, it provides a practical game plan/template that can be tailored to individual needs. Finally, some research findings will also be provided.

Logistics

Acquiring physical and virtual spaces

Working with the Provost’s office, we were assigned two physical rooms and were allowed to use them for the purpose of this project, one of which we used as our staging area, where we could brief and debrief with the players, monitor and facilitate the games by providing feedback and scaffolds during the gameplay via a Zoom connection, and workshop games with developers, and the other one as the actual escape room where we could set up and play our games.

Later, we were also able to obtain a second game room from the university library for use as an EER two days a week, hence a study/escape room.

Room designation took about one term to complete, so, in the meantime, we created a Canvas course where we shared resources with interested faculty, staff, and students and engaged in conversations, discussions, and collaborations on game development. This virtual space is still being used alongside the physical space to collaborate and also share digital EERs provided through BreakoutEDU (see Game Development below). Finally, we launched the EER website, where we could offer game information and schedules, and the players could conveniently submit the consent form prior to gameplay and share their post-game reflections and feedback.

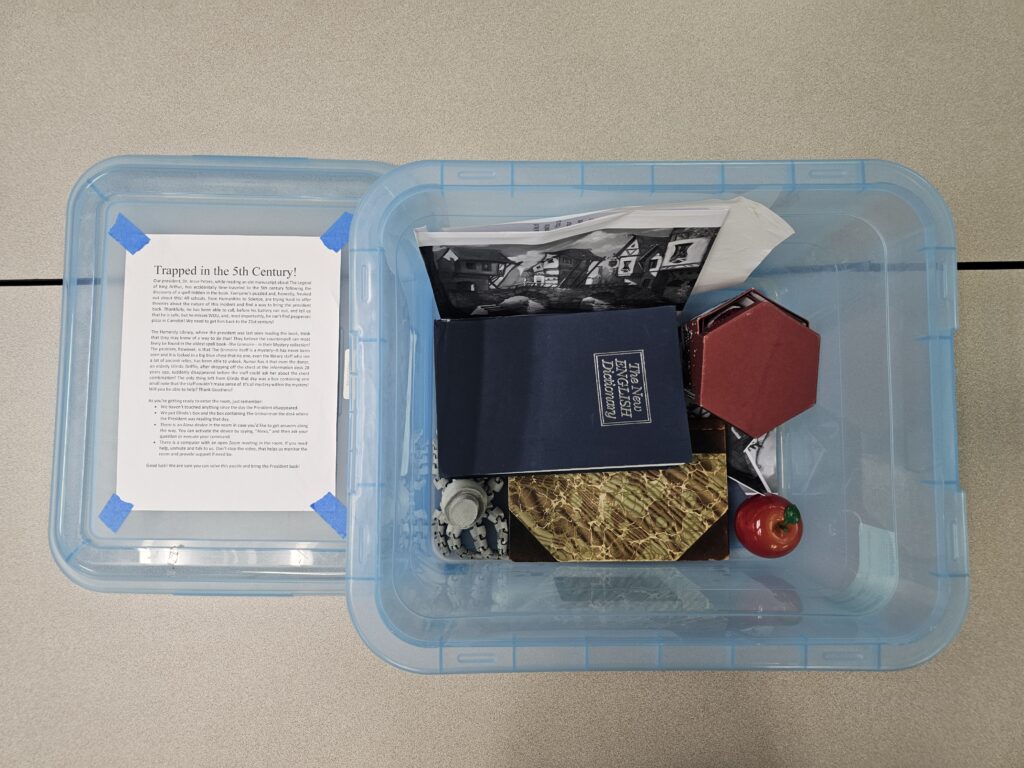

Acquiring and/or purchasing the EER items

To get the rooms up and running, we needed two types of items: furnishings and game-related items. For the former, we collaborated with the campus surplus unit and successfully acquired the necessary furnishings such as tables, desks, chairs, bookcases, decorations, closets, etc. Further, colleagues and units learning about our project donated various items in support (for example, the university IT unit supported us with 3 laptops, monitors, and computer peripherals), and we also kept an eye on various campus emails of different units surplusing their items. For the game-related items, we were able to secure a $1,000 grant through the university foundation, and used it to purchase various game items such as boxes, locks, props, educational posters, equipment, and technology. We also purchased two BreakoutEDU kits, which allowed us to have access to a consistent set of boxes, locks, and props across both rooms along with a 12-month subscription to their virtual game resources that we used in our Canvas course. It is worth noting that the purchased kits were great resources to get us started, but they are not necessary to have–as long as developers can follow a design framework, such as Clark et al.’s (2017; see below), they should be able to design their games and procure the items (locks, boxes, props, etc.) for them.

In addition to procured props, we also purchased a 3D printer using our unit’s funds to help us print our own props, making us independent and creative when it came to designing new escape challenges. With the furnishings and game-related items slowly collected, we had our physical and virtual spaces ready, and we needed games.

Game Design

Our subscription to the BreakoutEDU repository and the purchased kits (which we will renew if funding is available) gave us the opportunity to adopt and adapt various games based on discipline and academic level, which assured us that we could sustainably offer services to our campus community, but we also knew that we needed to be able to develop our own games, as we would be collaborating with our faculty members and other institutional units to turn lessons and trainings into escape challenges that our students could play; in others words, we needed both ready-made escape plans and also the ability to develop escape challenges based on our institutional needs. Therefore, looking through the literature, we came across Clark et al. (2017) framework, which conceptualizes an EER as having six key interrelated elements:

- Narrative: The overarching story or theme that frames the experience.

- Game flow: The structure and sequence of game phases and puzzles. EERs may have a variety of game flows, including a predetermined sequence of puzzles (sequential game), a more adaptable approach (open puzzle sequence), and hybrid solutions that offer multiple pathways.

- Puzzles: Challenges and problems for players to solve.

- Equipment: Physical and digital components used in the game.

- Learning outcomes: Targeted learning outcomes and process.

- Debriefing: Reflection after the game to connect experience to learning.

The framework further considers three contextual dimensions: The players/learners, design constraints such as time and space, and plans for evaluation. In other words, the process of designing an EER involves defining learning goals, developing a narrative, mapping the game flow, iteratively designing puzzles, incorporating equipment to set the scene, reviewing for learning, and playtesting at all stages. These elements should align to create a coherent experience that is engaging and educational, and we used this framework to develop our games.

Trapped in the 5th Century: An Example

Our first internally-developed game was a time-travel-themed game in which players embarked on a quest to bring back the president of the university who had inadvertently journeyed to the 5th century while reading a manuscript about The Legend of King Arthur. This narrative captured a moment in the university’s history when a new president had just been inaugurated, and we seized this opportunity to harness the school’s excitement for this change. Besides, this narrative gave us a chance to work directly with the president, who was very supportive of this initiative, and enhanced the immersive experience for players. To develop this game, we followed Clark et al.’s (2017) model, developing a shared Google doc where we gradually put together all the aspects of the game, that is, the narrative, the game flow, puzzles, instruments, learning outcomes, and debriefing. This exciting process was theoretical in nature, mostly thinking out loud, offering suggestions, placing comments, writing and rewriting, and, in general, discussing the dynamics, mechanics, and components of the game. Once we had a draft of the game plan, we were ready to test it in practice. For that, we called for groups of students, faculty, and staff members through our Canvas course and also word of mouth to join us for a play-testing of the game. In total, we play-tested the game 5 times, with the game going through many revisions (see the Student Engagement and Learning Outcomes section below to learn more) before officially opening it to the public through our website.

In what follows, I share this game as an example/model using Clark et al.’s (2017) framework. The structure, content, and procedure of this game are presented openly for use; readers may incorporate them into their own game development as they see fit.

Narrative

Our president, Dr. Jesse Peters, while reading an old manuscript about The Legend of King Arthur, has accidentally time-traveled to the 5th century following the discovery of a spell hidden in the book. Everyone’s puzzled and, honestly, freaked out about this! All schools, from Humanities to Science, are trying hard to offer theories about the nature of this incident and find a way to bring the president back. Thankfully, he has been able to call, before his battery ran out, and tell us that he is safe, but he misses WOU, and, most importantly, he can’t find pepperoni pizza in Camelot! We need to get him back to the 21st century!

The Hamersly Library, where the president was last seen reading the book, think that they may know of a way to do that! They believe the counterspell can most likely be found in the oldest spell book–The Grimoire– in their Mystery collection! The problem, however, is that The Grimoire itself is a mystery–it has never been seen and it is locked in a big blue chest that no one, even the library staff who see a lot of ancient relics, has been able to unlock. Rumor has it that even the donor, an elderly Glinda Griffin, after dropping off the chest at the information desk 28 years ago, suddenly disappeared before the staff could ask her about the chest combination! The only thing left from Glinda that day was a box containing one small note that the staff couldn’t make sense of. It’s all mystery within the mystery! Will you be able to help? Thank Goodness!

As you’re getting ready to enter the room, just remember:

- We haven’t touched anything since the day the president disappeared.

- We put Glinda’s box and the box containing The Grimoire on the desk where the president was reading that day.

- There is an Alexa device in the room in case you’d like to get answers along the way. You can activate the device by saying, “Alexa,” and then ask your question or execute your command.

- There is a computer with an open Zoom meeting in the room. If you need help, unmute and talk to us. Don’t stop the video, that helps us monitor the room and provide support if need be.

Good luck! We are sure you can solve this puzzle and bring the president back!

Setting/Equipment

The story unfolds in the library where the president was reading The Legend of King Arthur when he time-traveled. In the room, there is:

- a desk and four chairs

- a book on the desk

- the big BreakoutEdu box on the desk with 4 locks (shapes, ABC, 3-digit, and 4-digit) attached to a hasp, which is a locking mechanism enabling game facilitators to attach several locks to a single locking point (see Picture 6)

- an Amazon’s Echo Show (Alexa) device in the room (optional)

- a PC/laptop with a Zoom session on

- a UV flashlight

- boxes (clock with secret compartment, book with secret compartment, nesting boxes, storage box, apple-shaped container)

- a QR code

- puzzles and printouts

- a bookshelf and books

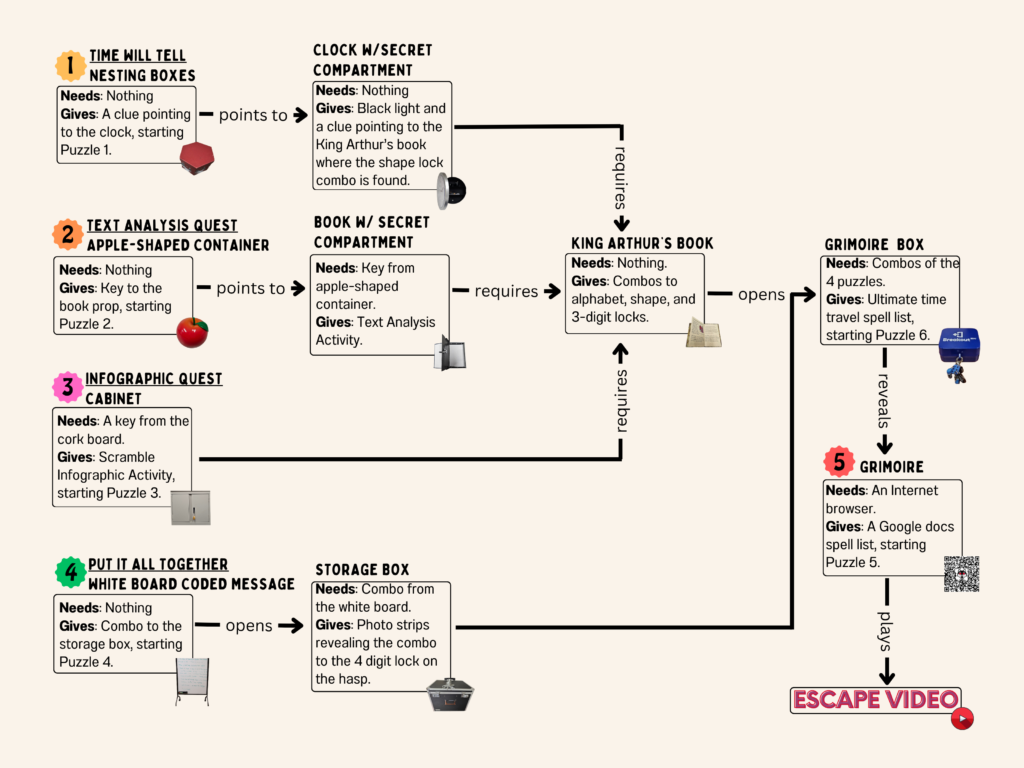

Game-Flow

Participants can proceed in a sequential fashion, meaning that the various tasks that they must complete can be done independently of each other.

Learning

This escape room supports students’ 21st century skills of critical thinking, creativity, communication, collaboration, social skills, and information and technological literacies.

Debriefing

At the end of the game, there is a focus group with the participants reflecting on and discussing the gameplay to connect experience to learning. Additionally, the BreakoutEDU provides a pack of 4C (critical thinking, creative thinking, communicating, and collaborating) cards that one may use to spark ideas and open conversations. The facilitator can let players draw random cards from the deck and try to answer and discuss the prompts. For example, the prompt may say, “Explain something new you learned through playing the game,” and this could be taken up by the focus group. The feedback could also be used for program evaluation and game revisions. After this session, the participants are awarded a Certificate of Completion.

Puzzles

In this section, I describe the puzzles that were included as various parts of the game.

Puzzle 1: Time Will Tell

The players find a note in Glinda’s Christmas box saying “Time Will Tell! Did you know that time can hide priceless treasures?” Following this clue, the players are directed to open the clock and find a UV flashlight and a piece of paper saying “It’s all in the shapes! King Arthur knows! The light reveals.” Following this new clue, the participants are directed to the King Arthur’s book on the desk where they need to use the UV flashlight to reveal the shapes hidden in the book. The combo (triangle, right arrow, star, square, circle;▲➡✶◾●) is written in invisible ink and unlocks the Shapes lock.

Puzzle 2: Text Analysis Quest

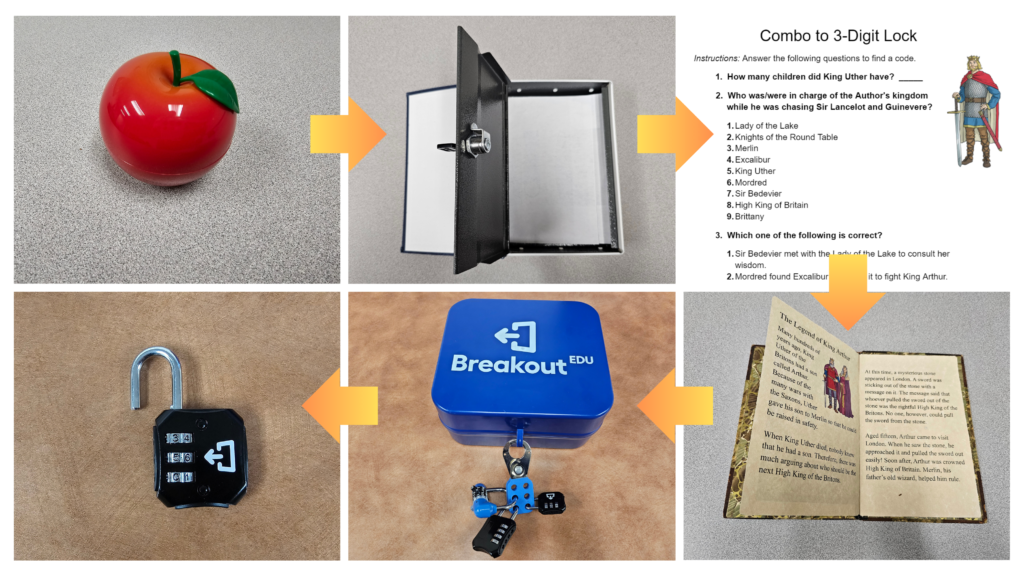

The players find a key and a clue, There is no frigate like a book to take us lands away!, in an apple-shaped container in the room. The key opens the book prop with a secret compartment on the shelf. The book contains a question sheet with three questions about King Authur’s story. The questions can be answered using the King Arthur’s book on the desk. The answers reveal the combination (1, 6, 5) to the 3-digit lock attached to the hasp.

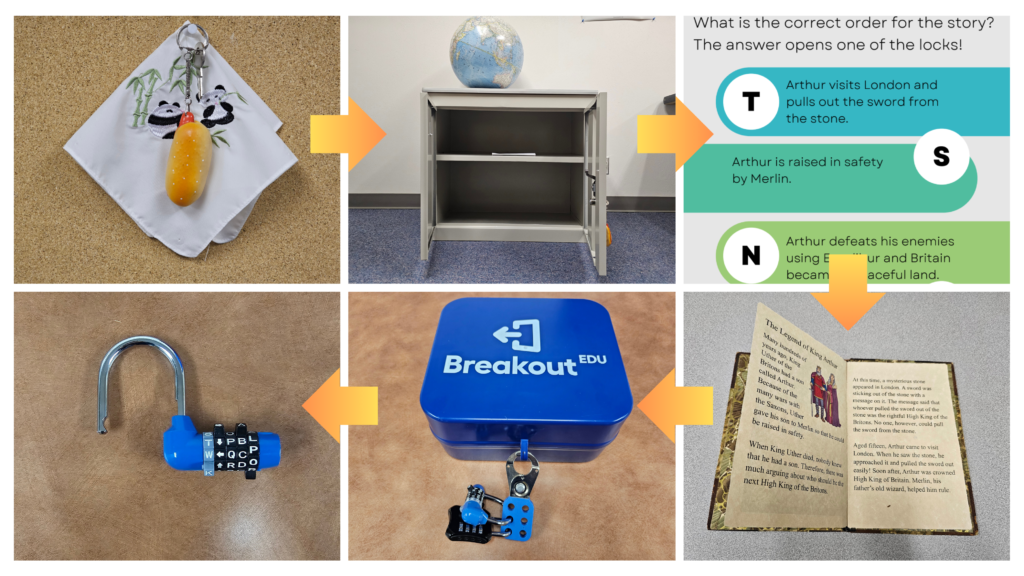

Puzzle 3: Infographic Quest

Using the key on the corkboard in the room, the players unlock the cabinet and find a scrambled infographic activity about King Arthur’s life in the cabinet in the room. The activity tasks the players with finding the correct order for the story to get a code (STONE) that opens the ABC lock attached to the hasp.

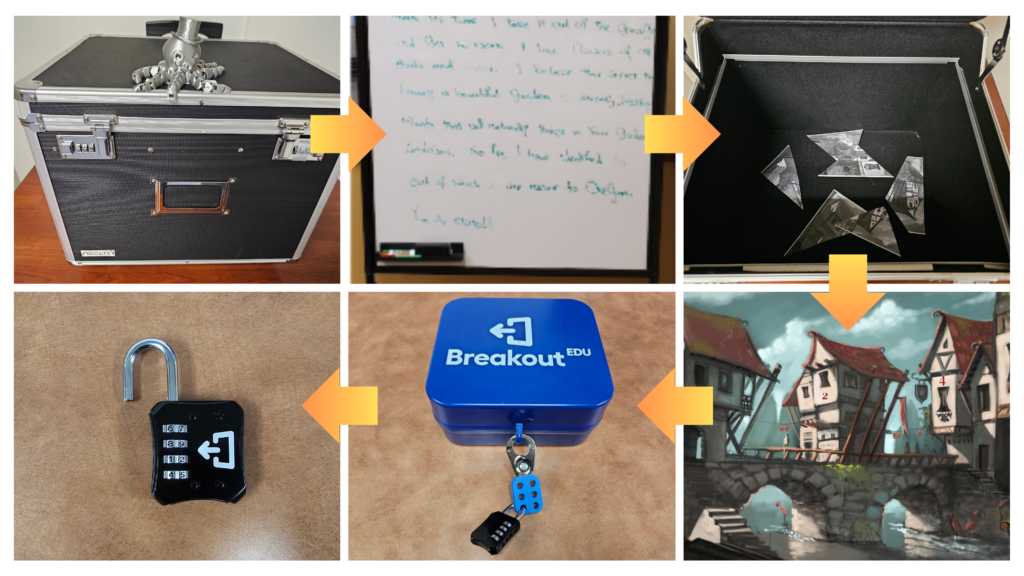

Puzzle 4: Put it All Together

The players find a clue inside a 3D-printed octopus on a locked storage box. The clue says, “Erase what you don’t need,” which refers to the whiteboard in the room with a New Year’s resolution note written in both permanent and dry ink (permanent ink words in blue and bolded below):

The idea of having a garden has always appealed to me. I have a storage box where I keep my gardening tools and I think it’s time I should take it out of the garage and get to work. You know, I like flowers of all sorts and combos. I believe the secret to having a beautiful garden is choosing strong, healthy plants that will naturally thrive in your garden’s conditions. So far, I have been able to identify 20 out of which 4 are native to Oregon.

When the players erase the board, the permanent ink remains, revealing the combination (204) to the storage box. The box contains photo strips that need to be put together to reveal the combination (3241) to the 4-digit lock attached to the hasp. The complete picture, on which the photo strips are based, is also printed out, framed and placed in the room for reference and as clue, and also set as the computer desktop background.

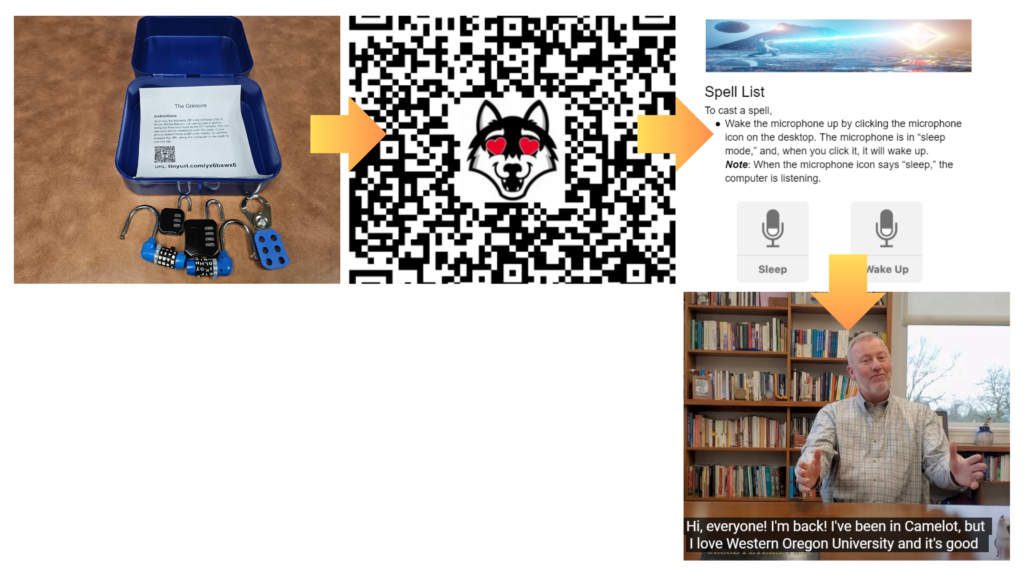

Puzzle 5: Saying the Magic Words

Having opened the four locks attached to the hasp, the participants open the big blue box where the Grimoire is. The Grimoire is a QR code and/or a URL that loads a Google Doc with 5 spells, one of which being, “Abracadabra,” helping the president get back to the 21st Century. There are instructions to help the players use the QR code using their own phones or the computer in the room. Once the Spell List is revealed, the participants use the instructions to cast the spell using the computer device in the room. When the correct spell is cast, the computer plays the president’s video saying that he is back, concluding the game. It is worth noting that, for accessibility purposes, the video is closed captioned and an alternate path to loading the video using the tool LearningApps has also been provided in case the code cannot be spoken.

In concluding this section, Picture 12 delineates the game roadmap. Furthermore, a promotional video showcasing the room setup is available for perusal, along with a repository of all the files integral to this EER.

Room Reset

While not a design step but rather a facilitation one, after each game session, the room must be reset. This involves returning all puzzles, locks, and clues to their original positions, ensuring all props are in place, and preparing the room for the next group of players. This step was performed by our staff.

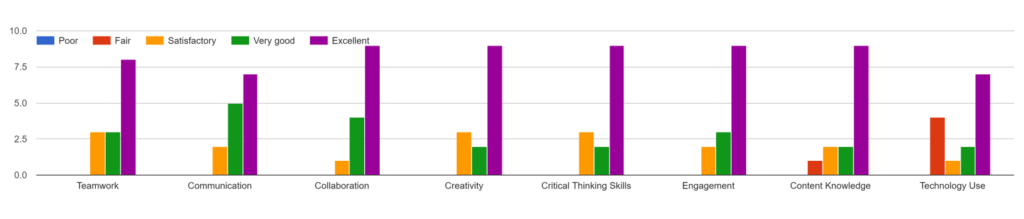

Student Engagement and Learning Outcomes

Based on a pool of 54 participants (28 students; 17 staff members, 11 faculty members), the results of the post-game surveys along with the debriefing focus group interview conducted on the effectiveness of this EER were positive and optimistic. The recurrent theme in the analysis was “fun” associated with the codes, “fun,” “super fun,” “exciting,” “interesting,” “cool,” and “super cool.” All participants who filled out the survey expressed the likelihood of recommending the EER to another person, and most participants saw it (through a combination of “fair,” “satisfactory,” “very good,” and “excellent” ratings) as useful in supporting their teamwork, communication, collaboration, creativity, critical thinking, engagement, content knowledge, and technology use (see Picture 13).

The difficulty level of the game was perceived as 2/3, with most participants rating the quality of their effort as “satisfactory,” “very good,” and “excellent” (see Figure 14). The average time spent on the game was around 20 out of the 45 minutes allotted.

Some comments on the game elements during the play-testing phase included:

1. The game rule on the consent form about not moving objects in the room was confusing to one group. The participants did not know that they could open the clock prop. However, they figured it out later when they decided to inspect the clock and “not move it.” We considered this part of the “critical thinking” objective of the game. One participant, who had played many escape rooms before, noted that we could add the “pinkie pressure rule” (if you can’t move something with your pinkie, then you don’t need to move it at all) to the list of escape room rules, which we did.

2. One group pointed out that the Shapes lock was hard to unlock. This experience resulted from the dials not being set properly. We had a similar problem with the 3-digit lock combo, but that was due to an error in the puzzle. We fixed both issues.

3. The clock and book props were the participants’ favorite of all of the puzzles in the room.

4. One of the players suggested that the hot dog-shaped keychain be changed to something which fit better with the medieval theme of the game, which led us to planning to 3D-print a medieval-ages object for a key ring–something like a sword.

5. The participants found the parallel gameflow, the game dynamic in which individual puzzles could be tackled by team members separately, very useful, as it got everyone engaged and busy during the game. One participant said that despite their ADHD, they did not get bored with the game design, as it was stimulating the whole time.

6. The Zoom link between the facilitators and participants was very useful and served our needs during the game.

7. The participants were able to operate the iMac machine conveniently.

8. We found out that we needed a better camera in the room so that we could observe most of the room. The iMac machine’s camera covered a small area in the room.

Some written feedback included:

- I love it when two or more things in the room coincide with one another visually. In this case, I loved how the picture puzzle matched the computer wallpaper. That really made my neurons buzz. 🙂 Not necessarily that it helped me figure it out, but it just stimulated the sense of meaningfulness of the game. Also I really liked having the old-looking book to sift through. It felt more interesting than looking everything up on the computer.

- We were all a bit nervous – and once we did it we realized we had nothing to fear! It was a great experience!! There is even talk about trying the other one now!

- The creative way to give us clues was great!

- I loved the blacklight! It was useful and fun.

- I think it would be fun to have more theme-based decor or clues. For instance, it would have been super interesting for the clue about “It’s all in the shapes.” to have had theme-based shapes to coincide with the lock combo. For example, a poster somewhere of King Arthur at his “round” table under a “starlit” sky, with an archer pointing his “arrow” at something, and someone wearing a “diamond” ring, etc. The elements of the image could be arranged in order or be represented in number. Example: 1 round table, 2 stars, 3 arrows, 4 diamonds, etc.

The survey results provided us with invaluable information on how the participants perceived the game mechanics and the learning aspect of the experience. We took the feedback from the results and revised the game experience, and the research component of the process will continue in the future for every game we design.

Accessibility Considerations

In EERs, escaping is key. This does not mean that the EER experience cannot be challenging, but, similar to classroom experiences, there should be ample amounts of feedback and scaffolding in the room, so that the players can escape. In addition, game facilitators must be available as a resource during the gameplay in case the players are stuck and need support. The Zoom connection in the room in our case, therefore, was an essential component of our EER to monitor the gameplay and provide just-in-time feedback and scaffolds to support the players as they went through the experience, just as how educators provide such support when facilitating their lessons. In addition, providing just-in-time feedback, which is feedback that is provided not too early or too late during the teaching/learning experience is a task engagement facilitator based on Egbert et al.’s (2021) model and helps keep the players engaged in the task, which is very important, especially in an EERs experience.

When considering the bigger picture, to conclude this section, all accessibility considerations, including physical, document/materials, and learning must be ensured in an EER. Unlike commercial escape rooms, which may include distractions and deceptive elements which raise the ambiguity and difficult levels of the game, EERs prioritize ensuring a high success rate for participants to meet educational objectives (Veldkamp et al, 2021), as an EER is an educational experience–it is a lesson turned into a game. For example, while a timer in the room can create a sense of excitement, if the students feel that a time limit is overwhelming, and this game element is not part of the educational objectives of the lesson, it should be adjusted/removed, just as how educators change time limits on speed tests depending on the learning objectives and student needs. Further, in the same vein, any aspect of the game, including modalities and group dynamics, should follow principles and best practices in universal design and accessibility to leverage the medium as an inclusive teaching/learning tool.

EERs and Language Learning

EERs, supporting the development of 21st-century skills, offer an immersive environment for language learning. Through engaging challenges and puzzles, students can not only practice language skills and components but also develop critical thinking, problem-solving, communication, collaboration, and creativity. The interactive nature of EERs could encourage active participation, negotiation of meaning, and foster a sense of teamwork among students as they work together to decipher clues and unlock mysteries (Makri et al., 2021), and, moreover, the real-world context of the EER tasks could provide authentic language practice, helping students apply their linguistic knowledge in practical situations.

Trapped in the 5th Century, while not directly addressing linguistic learning objectives, supports the development of 21st century skills that research finds key in language development (Egbert & Shahrokni, 2018). Language educators can develop online or face-to-face escape games focused on the development of specific educational objectives. For example, in a face-to-face game, Save the Commas, a game co-designed with colleagues from Washington State University, we aimed to teach English grammar, specifically the use of commas. The challenge revolved around a Comma Monster wanting to eat all the commas, as the students did not use them correctly, so the players needed to join efforts to learn about “the four comma rules” by solving different puzzle tasks in the room and ultimately beat the Comma Monster:

Hehehe! It’s me, the Comma Monster! Your class keeps forgetting to use commas and sometimes doesn’t put them in the right places, so I’m gonna take them and eat them! Yum yum yum! When I get your commas, your writing won’t make any sense! You won’t understand the stories you read, and no one will know what you mean when you text or email them. That means you won’t have any fun learning at all! Oh, I’ll give you one chance, though! Because I’m so nice! The only way to stop me from taking your commas is to review the four rules for comma use and solve the puzzles I’ve left for you in the classroom. Do you have a copy of the comma rules? No? I bet the teacher has one on their desk. You better hurry and find him and get started because you only have 45 minutes to solve the puzzles before it’s too late. Haha! Good luck, not really!

Stollhans (2020) also describes and evaluates the use of their EER focused on the idiomatic uses of German modal verbs. Moreover, in the absence of a physical space, online EER challenges could be engaging tools in teaching language skills. For example, in my Living Room Escape, I used Google Slides and Forms to review past and present tenses and some everyday vocabulary items (see Huang (2013) for multiple digital EER examples and instructions on how to design them). Therefore, the medium of EERs could be considered another effective tool in language educators’ toolbox to support them in teaching content and competencies in an engaging way (see Kuehner’s resource page for a collection of useful escape room design links).

Conclusion

We started an educational escape room (EER) on campus, with the results being overwhelmingly positive and in support of this educational tool, indicating that game-based learning (GBL) can help support students’ learning and engagement across disciplines on our campus. For future work, we aim to:

- continue collaborating with our students, faculty, and staff in developing new games aimed at various skills and competencies as well as levels.

- make our games scalable, with each game being packaged, shared, and reused across the campus and other academic settings (see Picture 15 for an example).

- continue researching the potential of GBL and EERs in enhancing student engagement, learning outcomes, and performance across various contexts.

Creating an EER can be useful–as De Koven (2016) notes, we are “inherently” playful, and given the chance, the health, the safety, and the freedom, we play– “together, separately, mind, body, soul” (para. 2-4)–it can serve as an engaging teaching/learning tool for all students; it can serve as a GBL model for faculty and future teachers, showing them ways to engage their students, implement and research new technologies, and facilitate the development of 21st century skills. The creation of an EER is affordable and impactful; as Martens and Crawford (2018) note, EER use

- …“builds a foundation for innovators of the future” by supporting learners’ innovative thinking (p. 69).

- shows teachers not how smart students are, but “how they are smart” (p.70)

- can “cultivate wonder” (p. 72)

- helps teachers think about “instructional decisions that teachers need to make in order to cultivate wonder,” including:

- “Opportunities to theorize and make predictions” (p. 72).

- Taking risks.

- Responding to students in real ways.

- Modeling wonder/curiosity.

- “Personalize and challenge students’ thinking” (p. 72).

- Explore content in new ways.

- Creating “freeing” learning experiences (p. 74).

Acknowledgements

The development of WOU’s Educational Escape Room (EER) was made possible through funding from the WOU Foundation, as well as additional donations from University Facilities, Library and Academic Innovation, and University Computing Solutions. Stellar support from the President’s Office, the Provost’s Office, Library and Academic Innovation, Office of Disability Services, and DEI Office has been instrumental in bringing this project to fruition. I would like to extend a heartfelt gratitude to the students of WOU whose enthusiasm and excitement have always served as a constant source of inspiration and encouragement for me. I would like to express a sincere thank you to my wonderful colleagues, Ben Hays, Adrienne Allardt-Wong, Sean ONeal, Mindy Khamvongsa, Chelle Bachelor, and Amy Dawson at the Center for Teaching and Learning for their unwavering support, as well as to Michael Reis, my amazing former supervisor, for his invaluable support of this initiative. I am also deeply grateful to my dear professor and friend, Joy Egbert, whose inspiration during my time at Washington State University ignited the idea of educational escape rooms within me. Last but not least, I am immensely grateful to Bev West and Rob Willingham for their invaluable assistance in coordinating the room assignment process, Nora Solvedt for procuring all and donating many of the EER items, Jackson Stalley for donating valuable items, Nathaniel Elder and Kevin Noreen for skillfully crafting the ancient book of The Legend of King Arthur, and to all our wonderful play-testers, especially Lucia Martin and Lili Minato, avid contributors to our testing efforts, for generously taking the time to play potentially-defective games and providing invaluable feedback.

References

Clarke, S., Peel, D., Arnab, S., Morini, L., Keegan, H., & Wood, O. (2017). EscapED: A framework for creating educational escape rooms and interactive games for higher/further education. International Journal of Serious Games, 4(3), 73-86. https://doi.org/10.17083/ijsg.v4i3.180

De Koven, B. (2016, September). Are we inherently playful? Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/having-fun/201609/are-we-inherently-playful

Dilek, S. E., & Kulakoglu Dilek, N. (2018). Real-life escape rooms as a new recreational attraction: The case of Turkey. Anatolia, 29(4), 495-506. https://doi.org/10.1080/13032917.2018.1439760

Egbert, J., & Shahrokni, S. A. (2018). CALL principles and practices. https://opentext.wsu.edu/call/

Egbert, L. E., Shahrokni., S. A., Zhang, X., Abobaker, R., Bantawtook, P., He, H., Bekar, M., Roe, M. F., & Huh, K. (2021). Language task engagement: An evidence-based model. TESL-EJ, 24(4). http://www.tesl-ej.org/wordpress/issues/volume24/ej96/ej96a3

Grande-de-Prado, M., Garcia-Martin, S., Baelo, R., & Abella-Garcia, V. (2020). Edu-escape rooms. Encyclopedia, 1, 12-19. https://www.mdpi.com/2673-8392/1/1/4/pdf

Huang, W. (2023). Digital educational escape rooms in language classrooms. The FLTMAG. https://fltmag.com/digital-educational-escape-rooms

Lopez-Pernas, S., Gordillo, A., Barra, E., & Quemada, J. (2019). Examining the use of an educational escape room for teaching programming in a higher education setting. IEEE Access, 7, 31723–37. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2902976

Makri, A., Vlachopoulos, D., & Martina, R. A. (2021). Digital escape rooms as innovative pedagogical tools in education: A systematic literature review. Sustainability, 13(8), 4587. MDPI. https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/13/8/4587

Martens, S., & Crawford, K. (2018). Embracing wonder and curiosity: Transforming teacher practice through escape room design. Childhood Education, 95(2), 68–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/00094056.2019.1593764

Nicholson, S. (2015). Peeking behind the locked door: A survey of escape room facilities. https://ischool.syr.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/erfacwhite.pdf

Shahrokni, S. A. (2024, January). Sprinkling enchanting pixie dust on teaching and learning with gamification. The FLTMAG. https://fltmag.com/teaching-learning-gamification

Stollhans, S. (2020). Designing escape game activities for language classes. In A. Plutino, K. Borthwick, & E. Corradini (Eds.). Innovative language teaching and learning at university: Treasuring languages (pp. 27-32). Research-publishing.net. https://doi.org/10.14705/rpnet.2020.40.1062

Veldkamp, A., van de Grint, L., Knippels, M.-C., & van Joolingen, W. (2021). Escape education: A systematic review on escape rooms in education. Educational Research Review, 31, 100365. 1-18. http://10.1016/j.edurev.2020.100364

Thanks for your comment! Educational Escape Rooms could work well for a variety of subjects, including STEM, history, language arts, and more. They can be used to improve learning by providing hands-on, experiential activities that require students to apply their knowledge in creative and practical ways to solve puzzles and work together, which has the potential to enhance their understanding, retention, and application of the material, while also developing critical 21st-century skills. I hope this helps! 🙂

I appreciate your educational insights. What subjects do escape rooms work best for, and how can they be used to improve learning?