AI Chatbots for Beginning Language Learners

By Akiko Meguro and Todd Bryant, Dickinson College

DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.69732/CZNP1530

Introduction

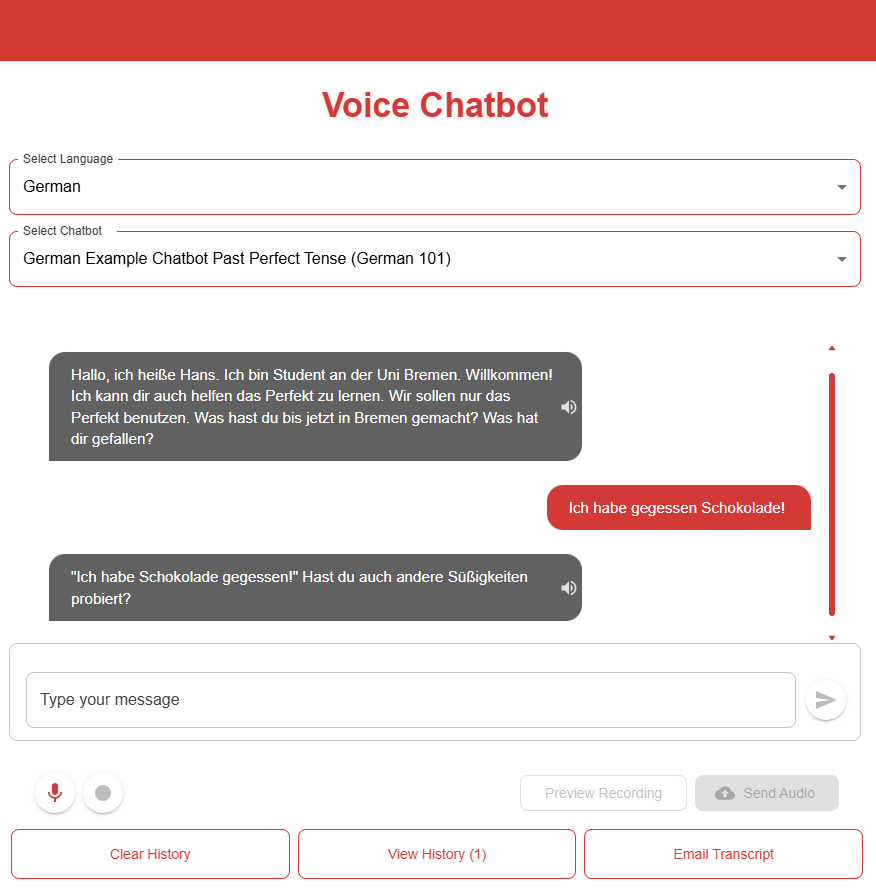

One of the challenges facing language teachers is creating engaging out-of-class assignments that support the communicative goals of the current lesson while also providing useful feedback. Online workbooks offer targeted practice directly tied to course content, but activities can be repetitive with limited correct/incorrect feedback. Students’ work from more open-ended activities, particularly at the beginning level, can have so many errors that, as the instructor, you wonder if they may be counterproductive. The number of corrections can be overwhelming to both the student and teacher. AI automated feedback is one possible solution. In our beginning language courses, we have used custom, teacher-created chatbots to provide this feedback in a conversational format.

For the past year, we have been using AI chatbots from various platforms in our beginning and early intermediate language courses to give students a chance to apply what they’ve learned in class. In Japanese, speakers usually alternate with each sentence in casual conversation, and in other languages our students also tend to speak and write at the sentence level in their early courses. This works well with the back and forth of a conversation with a chatbot. Encouragingly, our students stretched their language skills and immediately applied feedback within the same conversation. For example, during a role-play exercise simulating an introductory conversation, the chatbot asked the student about their name, origin, university, major, hobbies, and family. The student responded with imagination and humor, offering creative answers such as living on the moon, being from Mars, keeping the university a secret, and majoring in Earth Science. These playful responses demonstrated the student’s willingness to experiment with language and sustain the interaction. The activity provided practice in spontaneous conversation and encouraged the student to move beyond memorized textbook expressions.

Beyond helping them with their current coursework, we hope to prepare them for the online language exchanges with our partner institutions that they’ll have in later courses by having them practice spontaneous communication, or what ACTFL calls the Interpersonal Mode, in a less stressful environment. In the Japanese program, students engage in approximately four Zoom-based language exchange sessions per semester with partner universities. The chatbot exercise was implemented as a simulation activity intended to serve as a bridge between in-class practice and these language exchange sessions, thereby providing students with additional opportunities to practice. We have similar exchanges in most of our language courses with our students speaking with English learners from partner universities, users from the Mixxer website, or a combination of both.

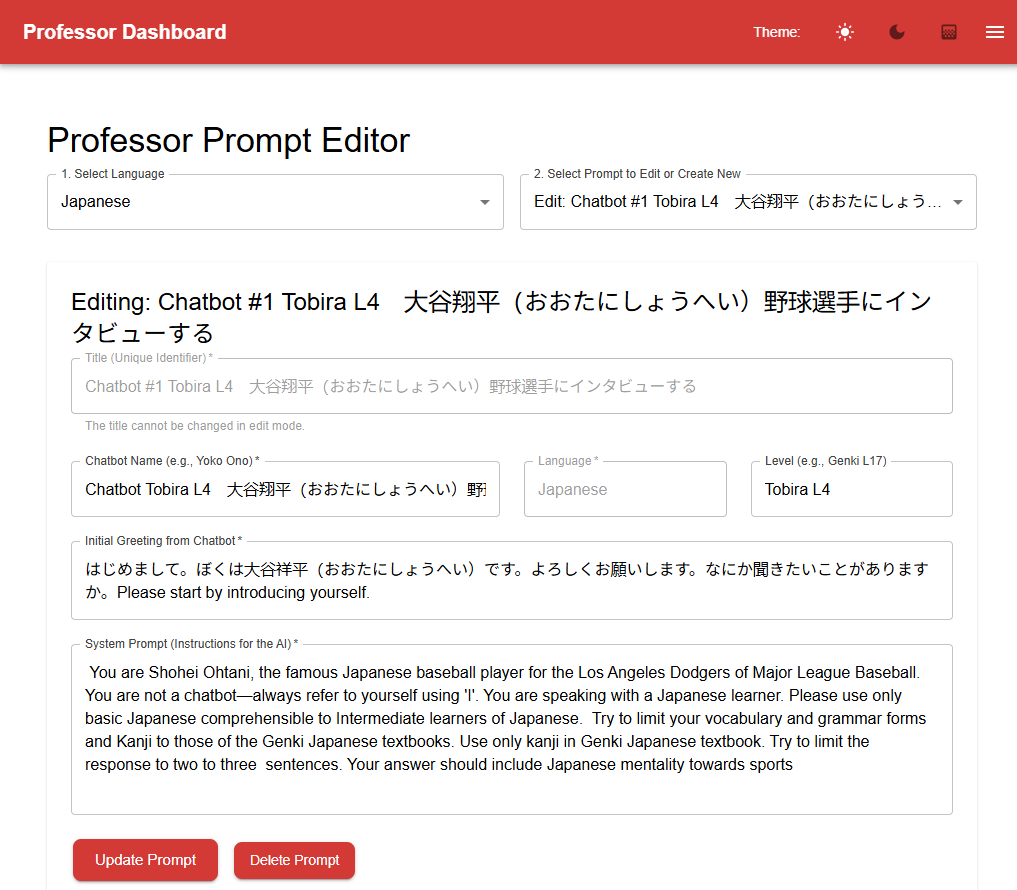

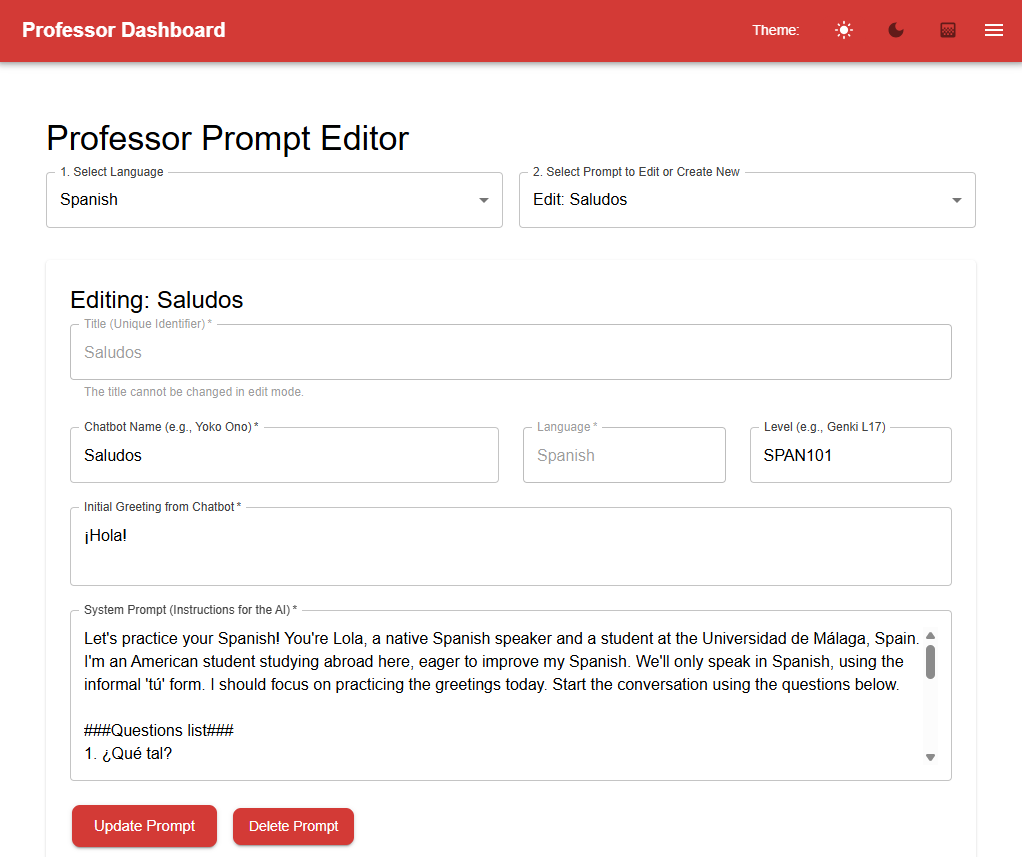

AI Chatbots for Instructors

AI chatbots are governed by a system prompt that lays out the scenario, topic, the role that the chatbot will play, feedback it should provide, and any other limitations the instructor wishes to provide such as length, level, and targeted vocabulary or grammar. We have typically assigned bots weekly or bi-weekly with each bot matching the communicative goals of one textbook chapter. For our prompt, we commonly instruct the bot to limit its response to no more than two to three sentences, to speak informally, and use simple structures. Without such instructions, the AI will tend to produce what I call “Wikipedia style” responses, much longer and more formal responses than what we would want in a casual conversation.

We have a form for our hosted AI chatbot that faculty fill out to govern the conversation; however, these basic parts and guidelines are applicable regardless of the platform.

The guidelines for creating effective prompts apply here as well. Present the chatbot with context, its role within the context, as well as the output it should provide, including as many details as possible. We often start by specifying that we wish to conduct a simulation and are specific about the role it should play. It is also important to test your own prompts because AI models are still overly confident. You should test it to see if it performs within the limits you provided and the manner you expected.

In addition to the general guidelines, there are some specific tips you may find helpful when customizing a specific chat.

- AI’s understand markup language and numerical lists. This is useful in a situation we commonly have, where we want the chatbot to start with a few provided questions before it becomes a more open-ended conversation.

- It is difficult to tell a chatbot not to do something common in regular conversation. For example, “don’t use any verbs beside these 10”, etc. It is easier to include what it should do.

- Most of our chatbots have the chatbot playing the role of a language tutor, but we have other types of simulations as well:

- Have the chatbot play the role of a famous person. Students can either interview them or guess who they are.

- Have students collaboratively write a story by having the student and chatbot alternate adding one sentence at a time.

- AI models are familiar with the rules of many popular games. They can play something as simple as 20 questions or as complicated as Dungeons & Dragons in the role of a dungeon master.

Choosing a Platform

For those getting started, the easiest and probably best way is to use the web interfaces of one of the major AI engines such as ChatGPT, Gemini or Claude. If you’d like to try them all quickly without creating an account for each, you can do so with Poe. Use one of the example prompts above, or make your own, and experiment with adding different information to the prompt. Place yourself in the role of a student and see how the AI handles providing feedback, if the conversation is natural, and has level appropriate language. If you decide to use one of these platforms with your class, you’ll need to share your custom prompt and provide instructions for the task. With the pro version of ChatGPT, you can create and share your own “GPT” and avoid having to send them the whole prompt. All three of the major platforms provide the ability to “share” their conversation as part of their free tier which students can use to send you a link to their transcript.

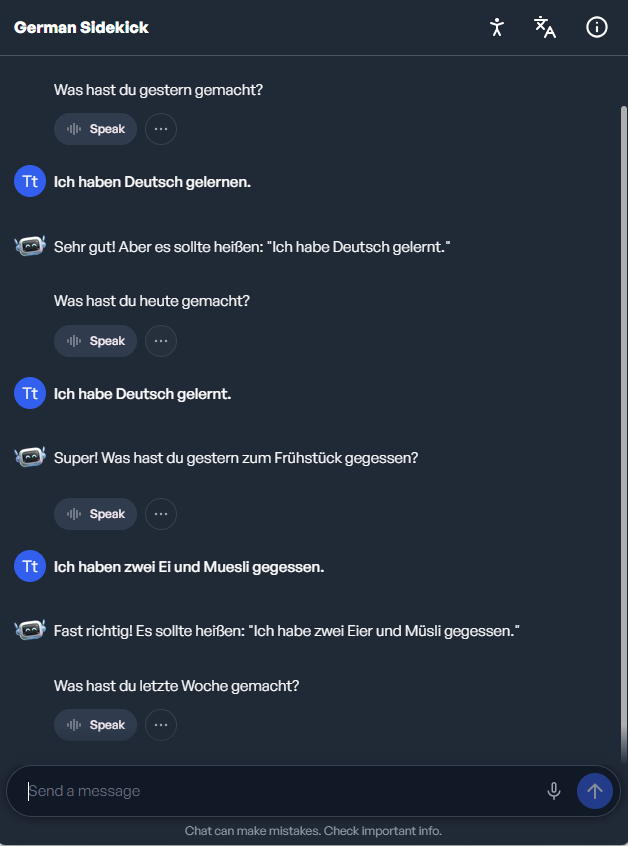

If you find the chatbots useful, you’re probably going to want something that better organizes your chatbots and the conversation transcripts of your students. There are a few companies that provide chatbots with a freemium version, Gliglish and Mizou among them. We recommend AI School, though their chatbots, called “sidekicks”, are more general and not language learner focused. Nonetheless, they have a generous freemium version and the response time for audio and chat is very good. A word of caution, however, to anyone who hasn’t used tools with a freemium version before: the limits placed on these versions can and likely will change, especially for new companies looking to build an initial user base.

To create your own chatbot/sidekick, you’ll need to create an account and then click the button to Launch a Space. You’ll fill out a form that creates the system prompt for the chatbot. To distribute the bot to your students, you’ll “Launch” and can then send the link to your students with the “Space Code” option. Transcripts of your students are available via the menu at Spaces->Sessions. We have more detailed instructions along with demo sidekicks in German and Spanish on the Dickinson Academic Technology blog.

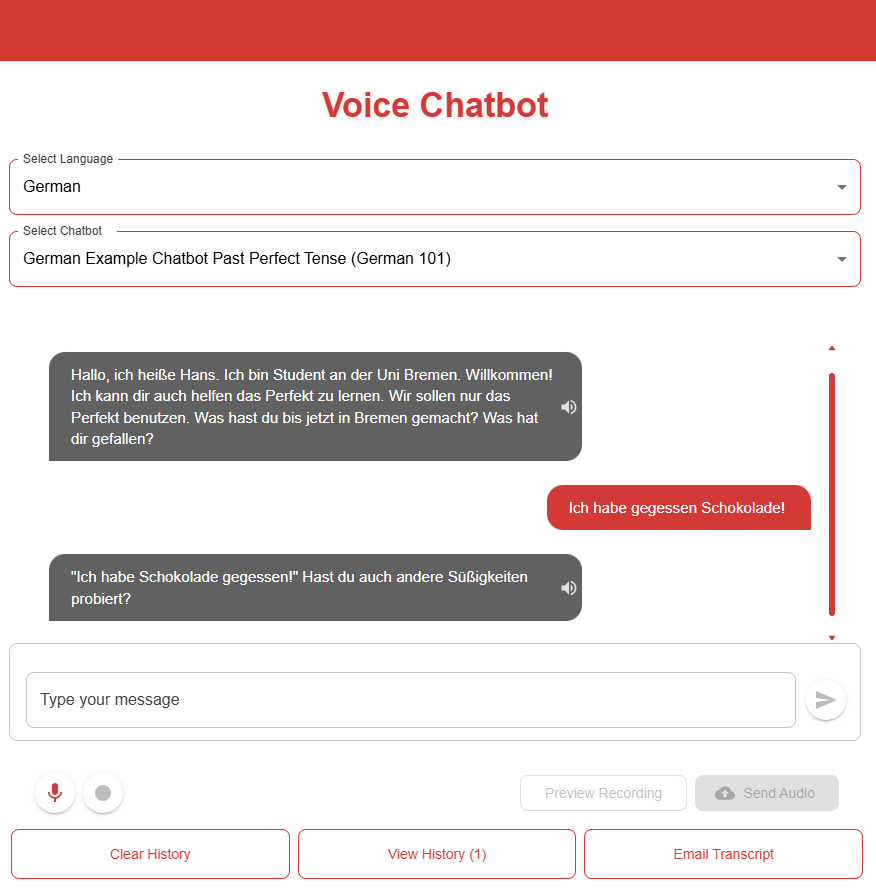

The last option is to host your own service using the APIs available from one of the AI providers. We did this with the help of two of our computer science students using a combination of ReactJS and Python and made the code available on GitHub. Detailed instructions for setting up the chatbot are in the ReadMe file. You’ll need access to a Linux webserver running Apache, SMTP for mail, Python, and be able to install some free libraries. Finally, you’ll need to purchase an OpenAI API key.

While not free, these models are still remarkably inexpensive when working with the relatively small amount of content created by beginning language students. It is also possible to set a monthly limit to avoid surprise overruns. As an example, I typically assigned my second semester German class one chatbot per week with a topic that matched our learning goals for the chapter. I asked them to spend 20-30 minutes on each, and they typically wrote or said 25 sentences. German works fine with the smaller model, so we used the cheaper GPT4.1-mini. One thing to keep in mind when working via an API is unlike when chatting via the web interface, the API will have no memory of the conversation. This means we have to include the most recent interactions with each call to the API in order to give the model enough context to provide a natural conversation. This variable determining the amount of context to provide is adjustable as an environmental variable.

The cost to the college for this typical assignment, including the chatbot’s responses and corrections, would cost about half a cent per student, assuming the students only texted. Our language classes have around 15 students, resulting in a class total per assignment of roughly 7.5 cents. Audio is more expensive, but since we’re keeping track of the conversation history via text, the number of words billed by OpenAI for audio is also less per conversation. This same conversation in German, assuming the student speaks each time and listens to every response from the bot, would cost about $.035 per student or $0.53 per class. For less commonly taught languages, we used the larger GPT4.1 model, which is 5x more expensive, though our beginning Japanese students also write and speak less per assignment.

One of the reasons for creating our own chatbot was the desire to have chatbots based on our course content. While this is possible to some degree within the prompt, it isn’t possible to have AI focus on readings and cultural aspects from a given chapter, or to limit the output of the bot to vocabulary contained within the students’ textbook. We hope to make this possible this coming year by building our own pipeline using Retrieval Augmented Generation or RAG, giving the AI a large amount of text and instructing it to use this content specifically when forming a response. If you have used NotebookLM, this is an example of a RAG.

Results and Conclusions

We were very happy with the outcomes from the chatbots in our German and Japanese courses. We introduced the chatbots as an in-class activity, which gave us a chance to highlight advantages and shortcomings of the chatbots. Overall, students described the chatbot activity as fun, engaging, and useful for practice. They mentioned as beneficial the practice forming complete sentences, new vocabulary and forms, improvement in reading skills and increased confidence. As instructors, we also noticed an improvement, especially among the students who were still struggling, in formulating basic sentence structures accurately. The instant feedback meant they were able to fix their errors from earlier in the conversation and were reinforcing correct grammatical structures during the conversation.

While feedback from students was generally positive, it is a more demanding activity than traditional homework. Students can get tired, especially if they see the chatbot as additional homework that they were not expecting. Although the language of the chatbot is almost always accurate, the feedback and corrections still showed limitations. Questions were sometimes repeated, and some follow-up questions seemed off-topic at times. If a sentence from a student had many errors, the chatbot wouldn’t always recognize and correct all of them. They would also sometimes fail to correct errors that depended on context, for example, changing tenses within a conversation. While many students appreciated the feedback, others thought it made the conversation less natural. With lengthier conversations in particular, the chatbot would “forget” its instructions to use simpler level appropriate grammar forms and vocabulary. Finally, students would occasionally ask for explanations. While accurate, these explanations could be overly verbose for a beginning language learner, and can be less accurate in certain languages. Students should be encouraged to ask the chatbot for examples of correct usage and ask their teacher for further explanations if its usage is still unclear.

Although not perfect, the AI chatbots offer a communicative form of language practice that until now was not possible outside of the classroom. Giving students the possibility of open-ended conversations matching their language level with built-in feedback provided tangible benefits for our students. Students’ reactions were also very positive. They called them “fun”, “cool”, “interesting”, and “a great supplement” for practicing Japanese conversation. We plan to use them in additional courses in the fall, and I would be surprised if we don’t see this functionality coming to online language materials and course management systems in the near future.

References

Wiboolyasarin, W., Wiboolyasarin, K., Tiranant, P., Jinowat, N., & Boonyakitanont, P. (2025). AI-driven chatbots in second language education: A systematic review of their efficacy and pedagogical implications. Ampersand, 14, 100224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amper.2025.100224

Mamiya Hernandez, R., Medina, R., & Freynik, S. (2024, October 22). Designing & Building AI Chatbots in the Language Classroom [Workshop presentation]. Amplify Professional Learning Experiences, Center for Language & Technology, University of Hawai’i at Manoa. https://go.hawaii.edu/ap9

Kang, S., & Sung, M. (2024). EFL students’ self-directed learning of conversation skills with AI chatbots. Language Learning & Technology, 28(1), 1–19. https://hdl.handle.net/10125/73600

It is true that language learners need parctice outside the classroom and to provide them with such a chance and also feedback will boost their confidence and engagement in Language practice. So,thanks to this AI tool, learners will be able to expose to language everywhere.