Russophonia: A Project-Based Approach to Decolonizing the Novice-Level Language Classroom

By Kathleen Scollins, University of Vermont

DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.69732/TVLQ4656

Introduction: Manie Musicale… à la Russe?

Two years ago, I noticed that my youngest son had begun listening to some surprisingly catchy French-language pop at home. During the pandemic, we’d become accustomed to working at the living room table together, and even by the time he’d become a self-sufficient 8th-grader in 2023, the habit stuck – which is how, after a few weeks of hearing his new playlist, we found ourselves singing along (in various degrees of broken French) with singers like Zaho, Mentissa, Keen’V and other artists from across the Francophone world, from the arrondissements of Paris to the shores of Martinique and the Ivory Coast. The wildly infectious song compilation, it turned out, was associated with Manie Musicale: an annual bracket-style tournament, in which French classes from around the world vote for their favorites while competing to predict which of the 16 songs will be the most popular (Carbonneau and Fournier). It’s basically March Madness for the Francophone teen music scene – a playoff-style tournament format familiar to U.S. audiences through college basketball, in which songs compete through successive elimination rounds.

I’ve always used a fair amount of music in my own Russian language and culture courses – my students hear songs every day, whether as the text of a listening activity or as an immersive tool to define the linguistic-cultural boundaries of our class – so I immediately began scheming about how to incorporate something akin to Manie Musicale in my own classroom the following year. In the years following Russia’s annexation of Crimea, however, and particularly since its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, even the act of choosing music to play before class has become politically fraught: should we stick to songs with Russian lyrics, even as Ukrainians (and Georgians, Moldovans, and so on) struggle against Russian neo-imperialism – after all, we are still teaching the Russian language! – or does that practice now serve to reinforce the historical Russocentrism within the broader field of Slavic Studies?

Geopolitical Context: Post-Soviet Neo-Imperialism

In the wake of Russia’s 2022 invasion, the field of Russian and Slavic Studies finds itself in a moment of urgent self-reflection and redefinition. Whereas post-WWII waves of decolonization across Africa, the Middle East, South, and Southeast Asia prompted “rigorous academic discussions and scholarship of colonial legacies and tools of violence,” the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991 did not invite such post-imperial scrutiny (Kassymbekova, 2023). Historically, Russia’s unique model of “internal colonization” allowed it to evade inclusion in European imperial frameworks, even as it extended and violently maintained control over Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Siberia (Etkind, 2013); this colonial ambiguity, coupled with the Soviet Union’s self-presentation as an anti-imperialist force of national liberation, long shielded Russia’s colonial complexities from critical scrutiny. Accordingly, while scholars of French, Spanish, and other programs of language and cultural studies began incorporating postcolonial theory by the 1990s – later embracing the decolonizing imperatives of the 2010s in response to global activist movements like Black Lives Matter – Russian studies remained notably resistant to these shifts. Only in the past several years has the field begun to confront Russia’s imperial legacy in earnest, decades behind its more commonly taught – and critically self-aware – disciplinary counterparts. As a result, Russian studies is endeavoring to decolonize an imperial entity that many scholars only recently recognized as such, having largely skipped the stage of postcolonial reckoning; our efforts to recenter those perspectives and voices long obscured by the field’s Russocentrism are thus complicated, not only by Putin’s renewed assertion of Russia’s imperial ambitions, but by our own belatedness in turning the lens of postcolonial critique onto the culture(s) we study and teach.

Like any disruption to the status quo, the current transformation of Russian and Slavic studies is unfolding unevenly – and not without resistance. Faculty in the field, many of whom are trained only in the Russian language and literary tradition, are now attempting to reassess nearly every aspect of their professional responsibilities – from the authors and texts they teach, to their curricular goals, to their department’s very name. And this reappraisal shouldn’t end with diversifying reading lists, adding a few new courses, or swapping “Russian” for a more inclusive label like “Eurasian Studies”: beyond these initial steps, the neo-imperialist violence of Putin’s war in Ukraine demands a more structural overhaul of the field (Prince, 2023). Such calls for the radical restructuring of Slavic Studies align with efforts to decolonize language instruction more broadly: Macedo (2019) decries the “colonial nature” of the foreign language offerings in most U.S. universities, emphasizing the importance of instructors’ own critical engagement with “the history of linguistic imperialism” in order to avoid reproducing those colonial hierarchies in their own classrooms (pp. 10; 27-28).

Nonetheless, this moment is not defined solely by anxiety or obligation. There is, for many, an undeniable sense of optimism – an excitement in reimagining the field’s foundations and possibilities. Since 2022, our own program has introduced several new courses that incorporate artists and works “from the margins” of empire or interrogate the colonialist nature of the Russian tradition, and similar curricular expansions, textbook projects, workshops, and panels are emerging across the field. Yet for all this progress, one challenge remains largely unaddressed: while new content and frameworks are flourishing in English-language courses and upper-level Russian classes, such advances in beginner-level language instruction have lagged behind.

Pedagogical Context: Decolonizing the Language Classroom!

In some ways, our field’s current identity crisis arrived at a propitious time. As language instructors, of course, we’re used to a fairly rapid pace of pedagogical evolution; our profession often feels as dynamic as the languages and cultures we teach. While the last major “revolution” in second language instruction was arguably the late-1990s shift from Grammar-Translation to Communicative Language Teaching (CLT), the decades since have seen meaningful developments within and beyond the CLT framework. Indeed, our so-called postmethod era – defined less by rigid, prescriptive methodologies than by a plurality of flexible, context-specific approaches – has seen the emergence of several movements particularly well suited to supporting our decolonizing turn. The multiliteracies framework, for example, stresses diverse modes of engaging with texts, encouraging learners to analyze them in their full cultural, political, and semiotic contexts; the approach foregrounds interpretation and reflection as essential meaning-making practices, making it especially well suited to social justice-oriented instruction (Arens & Swaffar, 2005). Critical Language Pedagogy (CLP) emphasizes the social and political dimensions of language use, encouraging instructors to foreground questions of identity, power, and voice (Norton & Toohey, 2004). Intercultural Communicative Competence (ICC) invites learners to engage deeply with unfamiliar perspectives, reflecting on their own cultural assumptions while developing the skills to navigate across linguistic and cultural boundaries (Byram, 2020; Liddicoat & Scarino, 2013). And translanguaging pedagogy challenges the artificial L1/L2 divide, empowering students to draw on their full linguistic repertoires to construct meaning (García & Wei, 2014). Alongside these frameworks, motivational, student-centered strategies – such as task- and project-based learning, gamification, and student-generated content – have opened creative new possibilities in the classroom (Kokotsaki, Menzies, & Wiggins, 2016; Nuss & Kogan, 2023; Snowball & McKenna 2017). Within this rich and ever-evolving pedagogical landscape, the challenge is not merely to adopt these approaches for their own sake, but to use them in service of larger educational and ethical goals.

In our program, these provided a theoretical foundation for our decolonizing efforts in the elementary Russian language classroom; one such experiment – the Russophonia project – offers a preliminary model. The name Russophonia itself is intended to capture the tension between the celebratory and critical positions that distinguish this moment in Slavic and Eurasian Studies. It plays on the idea of a broad, transnational sphere of Russian influence (akin to Francophonie), while nodding to russophobia: a term that reflects our students’ – and, indeed, our own – ambivalence about centering the language and culture of an imperialist state even as it aspires to subjugate more than one of those cultures and communities represented in our bracket.

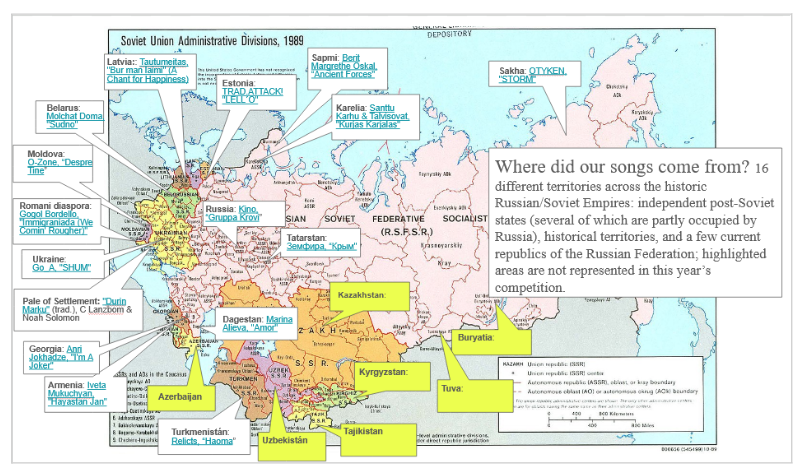

The Russophonia Project: Decolonizing from Day One

Our instructors were eager to extend the field’s decolonizing path into the lower levels of language instruction, but we faced a dilemma: how to decolonize an intro-level language classroom – particularly in a less commonly taught language (LCTL) – when our novice-level students are still struggling to get a handle on case endings (or even master a new alphabet)? Russophonia offers one possible pedagogical response to that question: a collaborative, project-based intervention that brings decolonial awareness into the beginner-level Russian classroom, with no prerequisite cultural or linguistic knowledge required. Like Manie Musicale, the model that inspired us, Russophonia presents a friendly, bracket-based song competition that helps students develop both Communication and Culture dimensions of the revised World-Readiness Standards for Learning Languages (NSCB, 2015). Unlike its French predecessor, however, our own project shifts the balance toward Culture – both to accommodate learners’ novice-level proficiency and to allow each post-Soviet nation, republic, or territory to be represented in its own language and voice.

Like many undergraduate language programs in the U.S., ours focuses strongly on developing proficiency; majors are required to take only a single literature course taught in English, so their cultural exposure is largely limited to what’s covered in language textbooks until they reach our upper-level content courses in Russian. Introductory-level textbooks have begun to address this gap – our first-year text, for example, features characters from cities less familiar to U.S. learners, including Kazan’ (the majority-Muslim capital of Tatarstan, in central Russia) and Irkutsk (a Siberian city near Lake Baikal, home to several Indigenous communities), offering a glimpse of the country’s vast cultural diversity. But our ethical mandate to decolonize compels action beyond what current materials offer. A major goal of our project was thus to reorient the cultural geography of the “Russian” language classroom, shifting focus away from Moscow and St. Petersburg toward the diverse peoples, histories, and musical cultures of the post-Soviet space. This shift in focus is valuable not only for its academic and moral imperative, but also for its practical relevance: the field’s study abroad landscape has changed drastically in response to the war, and our students are now likely to study in places like Yerevan, Tbilisi, Bishkek, Almaty, and Tallinn.

Project Overview

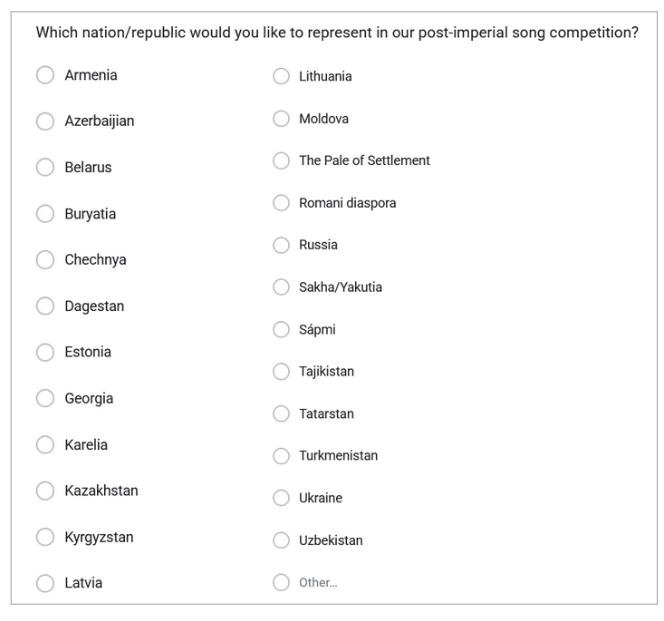

Students received an assignment sheet (outlining learning goals, steps, due dates, grading criteria) and a list of places to choose from. They were given the option to work individually or in pairs, depending on interest, comfort with presenting (and/or the technology involved), and selected place.

Once their choice of place was finalized, students were required to:

- Research its cultural, political, and historical context

- Select one song to represent it in the bracket

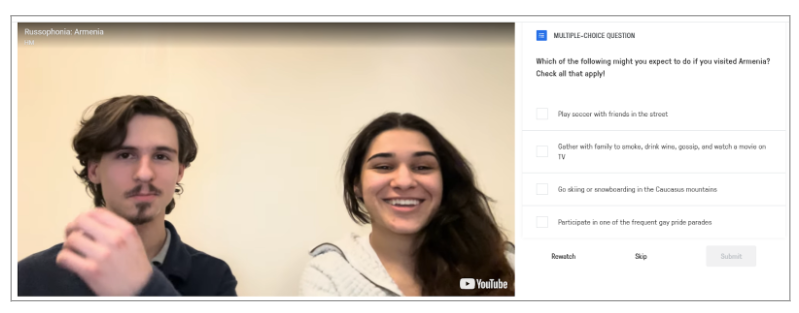

- Produce a short video presentation in English aimed at a general audience

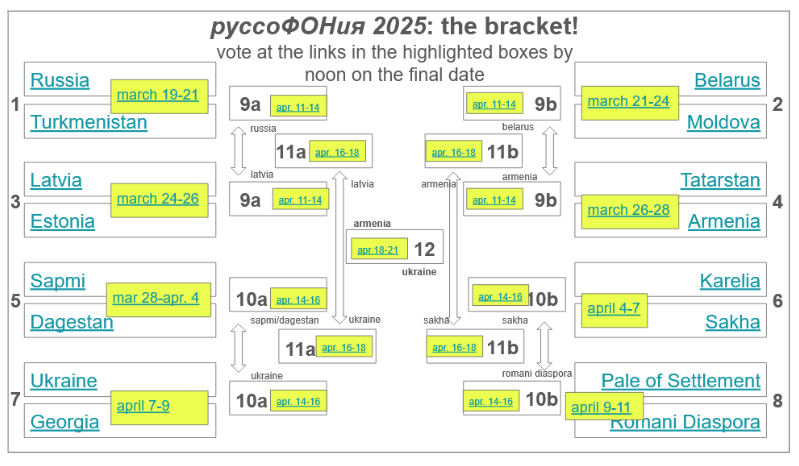

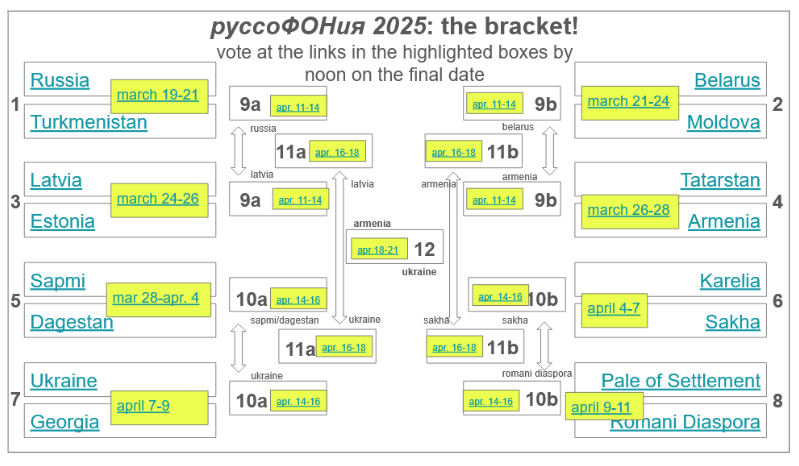

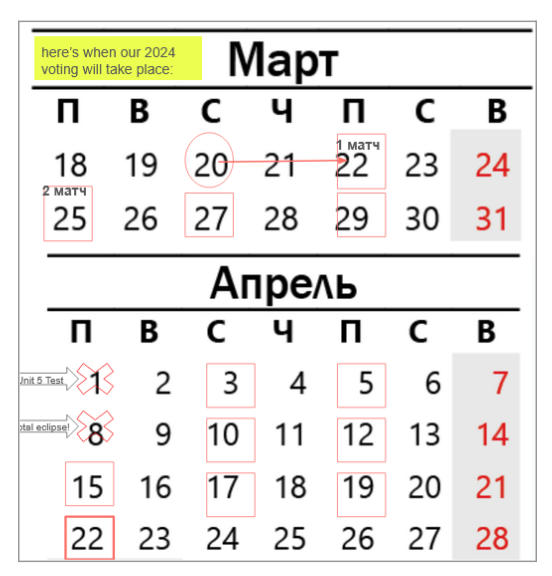

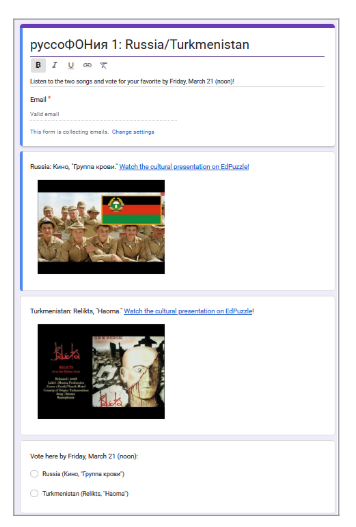

Song Choice: Song selection and video content were entirely student-driven. The assignment sheet offered only the following guidance: the song “will represent your ‘place’ (nation, republic, or otherwise) in our bracket. The song can be new or old, belong to any genre, and sung in any language. You can strategically choose a song in the hopes of winning the bracket, but you’re also free to choose a song you just want more people to hear, or a genre you want to learn more about.” Students finalized their song choice (via YouTube link) early in the process – this past year, by February 14 – and presentations were due February 28. Once I had all 16 songs, I organized the bracket. The matchups were loosely based on my sense of which songs might go far (to avoid strong early knockouts), while ensuring lesser-known places weren’t penalized for obscurity. Otherwise, bracket organization was pretty vibes-based. Students voted in single-elimination rounds through eight matchups until all 16 songs had been heard. The quarter- and semi-finals each included two matchups, and in the 12th and final round, the winner was chosen.

Presentation Requirements: in their brief presentations (5-10 minutes, in English), students were required to include key facts about their chosen place – geography, colonial history, language, religion, political system, current relationship to Russia – as well as a brief overview of the song and artist selected to represent it. Students were advised to use credible (though not necessarily scholarly) sources, including at least one regional or Russia-based outlet. The assignment sheet provided links to several such sources on the post-Soviet landscape, including The Moscow Times, RFE/RL, and Meduza, as well as comparative notes on Russian Wikipedia vs. its Kremlin-compliant fork, Ruviki. While all students receive foundational information literacy training through the first-year writing program at the University of Vermont (UVM), we also provided brief in-class guidance on evaluating source credibility and bias. Students completed this part of the assignment in English (unless they chose to use Ruviki for comparative purposes), making it accessible to second-semester learners while still encouraging critical engagement. They submitted their presentations as unlisted YouTube links, which I converted into EdPuzzles, embedding questions to track engagement. While students were not required to watch the presentations before voting, viewing classmates’ presentations was incentivized: bonus points on quizzes and tests, plus a final, cutthroat (but fun) Kahoot covering information from all presentations, offering bragging rights (and a small prize) for the winner.

In-Class Integration

The voting stage of the project lasted about four weeks in total; each voting round lasted two days, so results were announced (and a new round began) every Monday, Wednesday, and Friday of class, excluding test days. Links to all songs, presentations, and voting forms were embedded in the Russophonia slides (as well as their schedule of daily assignments), so listening, viewing, and voting took place largely outside of class.

The voting schedule enabled us to listen to each song again before class and discuss it in Russian, in a structured and supportive setting. Over the month of voting, students learned several constructions that enabled them to express opinions, including the dative case (for likes and dislikes) and quantification (for awarding 1-5 stars to each song). I was pleased to hear how quickly students became comfortable with these generally tricky constructions; even typically reserved students were eager to speak up about their likes and preferences, and several good-natured arguments broke out as they debated melody, lyrics, meaning, and beat with surprising investment. As much as possible, students used scaffolded Russian to express their opinions (and clearly found it motivating to have something shared to discuss, beyond the textbook’s storyline), though our brief discussions also invited deeper English-language questions about the artists, songs, and cultural contexts.

In this way, the bracket structure created opportunities for sustained, low-stakes cultural engagement over several weeks. And while the primary goal of the project was cultural exploration, several organic discussions emerged regarding language itself – particularly in response to the multilingual nature of many of the songs. Students noted, for instance, the strategic alternation of Kazakh and Russian verses in one rap song from Kazakhstan, or the use of a Russian-language chorus in a Tatar pop song. These observations led to broader questions about language families (such as the supposed mutual intelligibility of Russian and Ukrainian, or the far-flung distribution of Turkic languages, running east from Crimea and Tatarstan through Central Asian deserts, then north to the Arctic tundra of Sakha), as well as the politics of language choice and code-switching in post-Soviet popular culture.

Giving students complete control over the content resulted in a wildly diverse and equally catchy group of songs – in 2024, several of them actually turned up in my year-end Spotify Wrapped (and many from this past spring will no doubt make this year’s cut)! The game elements fostered (mostly) friendly competition, and students developed strong favorites as the bracket narrowed; the 2024 finals, between a pair of shoegaze-y emo teens from Sakha and an aging, avant-garde throat-singer from Tuva, was a nailbiter requiring two tie-breakers, and students were shockingly invested.

Check out some of the songs here!

имя твоей бывшей – pop group from Sakha

Yat-Kha – throat singer from Tuva

2024 Russophonia playlist

But by the end of the project, students had discovered more than 16 great new songs: they had accessed 16 unique languages and cultures, made historical and geographical connections they hadn’t recognized before, and begun to grasp the astonishing cultural diversity – as well as some of the colonial complexities – of this vast territory. One unexpected benefit of the project was watching the group grow as a collective as they began looking to one another as experts: political science majors provided context, English and music majors offered textual analysis, and students with roots in various regions had a chance to share their families’ experiences. The discussions that emerged covered everything from the impact of Eurovision to indigenous rights movements.

Pedagogical Principles at Work

Over the course of this multi-stage project, students actively participated in the type of meaningful and collaborative learner-centered inquiry that exemplifies project-based learning. Once they had chosen their songs and produced their video presentations, my only job was to arrange the bracket and remind them to vote – in other words, students were the primary generators of content. The high levels of engagement and excitement suggested that transforming students from passive consumers to active creators had boosted their sense of ownership and agency in the learning process. The “gamified” bracket format was similarly empowering, encouraging investment in the material and boosting students’ collaborative (and sometimes competitive) spirit.

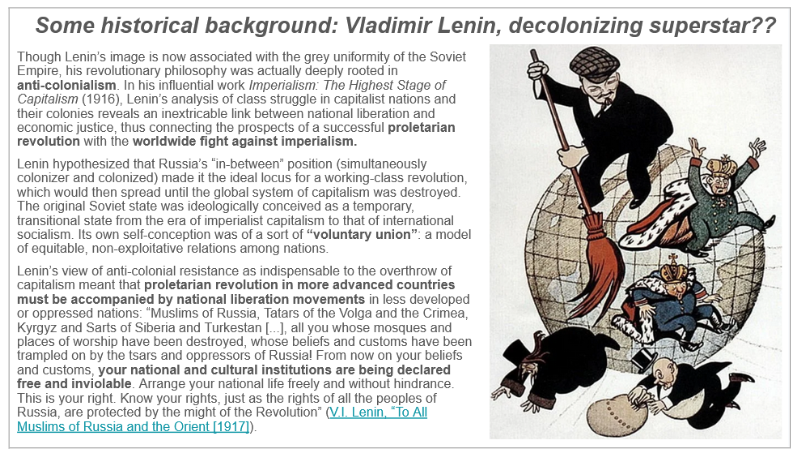

More broadly, the project cultivates the active, reflective practices essential to the development of intercultural competence (Liddicoat & Scarino, 2013, pp. 60-62). Its focus on imperial representation and resistance aligns with the field’s more recent turn toward Critical Language Pedagogy by challenging students to think more critically about how the language(s) they use and learn reflect and shape power structures and inequalities. For historical context, my introductory slides introduced Vladimir Lenin’s anti-imperialist vision of a “voluntary union of nations” – a vision that would eventually evolve into what Suny (1997) called the “most unique empire in the twentieth century” (Lenin, 1920). Lenin’s remarks were not included to idealize the USSR or validate its anti-imperialist self-presentation, but to invite students’ critical reflection on the region’s historical complexities. As discussed in more detail above, the name Russophonia gestures toward the contested notion of a Russophone analogue to the Francophonie, inviting students to reflect critically on the tangled ideological and political forces that shaped (and continue to shape) this vast territory – even as we explore its extraordinary musical diversity.

Tools and Adaptations: A Practical Framework for Instructors

While our own model was aimed at the novice-level of instruction, the Russophonia project is certainly adaptable and scalable to higher levels of student proficiency or other educational contexts. It could be adapted to various world language classrooms (not just Russian) at any level of instruction; to courses taught in English; or even across disciplines (e.g., postcolonial studies, music, media). And like the project itself, all tools could be swapped out for others that fit the instructor’s classroom, style, or university context better; the following tech tools are simply what worked well for us at UVM.

- Google Slides – central hub for assignment overview, instructions, historical background, bracket logistics, and all links. [link]

- Google Forms – sign-up form to assign places (using a “Choice Eliminator” extension); and later, a voting mechanism for the bracket.

- Spotify/YouTube – students sent their song choices as YouTube links; I curated playlists featuring all songs in the bracket in both YT and Spotify for easy listening.

- YouTube – Students uploaded their presentations to YouTube and sent me a link, which I embedded into the Google Slides (and used to create the EdPuzzle other students watched).

- EdPuzzle – I used this platform to embed questions in the students’ video presentations; the program allows me to track student engagement with their peers’ videos, which was helpful for accountability and grading.

- Email (or university LMS) – for sending reminders and voting results

Assessment: Reflecting on Intercultural Development

At UVM, we assess students’ cultural proficiency after both the second and fourth semesters of Russian language instruction. The prompt is open-ended and in English:

“Write two solid paragraphs (approximately 300 words total) describing one aspect of Russian or Eurasian culture that differs from or resembles your own. Choose something you’ve encountered in the course that reflects the culture, history, contemporary values, or perspectives of Russia (or the broader Russian/Soviet Empire). Then, in Russian, list five key words or phrases you associate with this cultural aspect.”

We began tracking cultural proficiency in 2021, as part of a college-wide initiative to assess student learning outcomes more systematically. Prior to the implementation of Russophonia in 2024, student engagement with cultural content varied. Some were so focused on language acquisition that they overlooked the rich cultural material embedded in our textbook. In fact, during the first year of assessment, only about half of our first-year students met or exceeded expectations in cultural proficiency.

In the two years since Russophonia was introduced, however, every first-year student has met or exceeded expectations. Multiple factors may contribute to this improvement (e.g., post-pandemic pedagogy, greater instructor experience), but it’s worth noting that most students chose to write about the cultural dimensions they explored through Russophonia. Many exceeded the expected response length and demonstrated deeper reflection and insight.

Tips for Teachers (and Room for Improvement)

- The first year I implemented Russophonia, I had 16 students in my second-semester course – a perfect number for a symmetrical, single-elimination bracket. The following year, we included both sections of second-semester Russian. To maintain a workable bracket, we allowed students to work individually or in pairs. But really, any number of songs can work; just search online for bracket structures that suit your needs.

- This past semester, students across two sections of Russian (with different instructors) participated. In some ways, this enhanced the competition, as the two sections began to vote as blocs to support their own classmates. However, if sections differ significantly in size or engagement, that dynamic could detract from the experience.

- While it’s great to offer students choices, a more curated list may lead to greater cultural variety. Ironically, expanding our “place” options this year led to less diversity: many students gravitated toward more familiar (Western) countries, so songs from Central Asia and eastern republics like Buryatia or Tuva were underrepresented. Next year, I plan to revise and rebalance the regional menu.

- The project has several steps, so it’s helpful to provide clear dates, expectations, and grading rubrics from the start. Scaffold the assignment in stages – song selection → research outline → script & slides → final video – and give students at least two weeks between choosing a song and presenting their video.

- If possible, provide model videos along with trustworthy research sources. I couldn’t do this last year because our 2024 submissions were on Flipgrid and I hadn’t saved them before that platform was disabled. Now that we’re using YouTube, I’ll make sure to archive and share a few examples for future students. Of course, I’ll also emphasize that there’s no fixed format – creativity is encouraged!

- I’m still experimenting with the best way to assign and evaluate students’ engagement with each other’s videos. EdPuzzles helped me track participation and effort but were time-consuming to create. Asking students to respond to an open-ended question on a Google Doc or LMS discussion board might be a more efficient alternative.

- Consider devoting even five minutes of class time to discussion and reflection: this gives students a chance to raise questions, share observations, and highlight underrepresented regions.

- Lastly, instructors should be aware that this is a time-intensive project. Even with the structure and materials in place, creating EdPuzzles and updating voting forms and links daily took a significant amount of time. But that time was more than justified by the depth of student engagement, the joyful atmosphere it fostered, and the measurable growth in intercultural competence.

- Please reach out if you’re interested in adapting this for your own classroom – or if you have feedback, questions, or suggestions for improvement: kscollin@uvm.edu.

Closing: Toward a Decolonial Classroom

Since the communicative revolution in language teaching, FL educators have worked to connect language and culture right from the start, incorporating level-appropriate tasks and texts “from menus and ads through poetry and drama” (Arens & Swaffar, 2005, p. 140). However, at the earliest stages of instruction – particularly in LCTLs – this ideal may fall short in fostering intercultural communicative competence (ICC), since students’ limited proficiency can prevent meaningful in-language reflection on cultural content.

Recent scholars suggest that strict L2-only policies may actually discourage early cultural engagement. Recommendations include encouraging cultural reflection outside class (e.g., through discussion board assignments) or permitting short classroom discussions in the students’ native language – or a mix of L1 and L2 (Karkour, 2022; Nemtchinova, 2020). As Nemtchinova observes, brief discussions in English can allow students to express ideas with more depth, without sacrificing content for vocabulary (p. 339). Anderson and Walsh (2020) go further, noting that college students are unlikely to find menu descriptions or advertisements intellectually stimulating. Their proposal – assigning “research-based Internet writing projects on Russian culture, current events, and topics of academic or personal interest” – strongly supports the use of L1 at the lower proficiency levels to boost cultural engagement and intellectual curiosity (p. 431).

Emergent theoretical frameworks also reinforce the value of L1 in the classroom: Zhang and Wei (2021) offer a translanguaging perspective to endorse the strategic use of L1 in language instruction (p. 115). Likewise, decolonial pedagogies seek to empower learners to draw upon their full linguistic repertoires (including using L1), by dismantling traditional classroom hierarchies and creating opportunities for them to take on more agentive roles in the processes of learning and teaching (Kimura & Tsai, 2023). Tochon (2019) links decolonial approaches in FL education to broader trends in pedagogy, including active learning and learner-generated content (LGC): deconstructing colonial hierarchies of language and culture (or at least rendering them visible), he insists, must go hand in hand with revising the role of learners, who emerge as “curriculum builders” in his upended classroom order (2019, pp. 273). Envisioning the renewal of Slavic and Eurasian Studies just before the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Garza (2021) agreed that any decolonizing efforts “must be transformative both in content and in manner of instruction” (p. 43).

The Russophonia project aligns closely with all of these pedagogical movements. At a moment when our field is undergoing long-overdue self-reflection, the imperative to develop students’ intercultural competence must, at times, outweigh the narrower goal of expanding language proficiency. This teaching experience has illuminated the power and potential in reframing beginner-level content – not by layering cultural material on top of grammar and vocabulary, but by treating cultural inquiry as a foundational component of the course itself.

As world language educators continue to reassess what we teach and how we teach it, beginner-level classrooms have a vital role to play in transforming our field. Russophonia is one example of how cultural learning and decolonial approaches can meaningfully shape students’ earliest experiences with language. It is my hope that this project might inspire further experimentation with student-generated, culturally situated content – not only in Russian, but across the curriculum.

References

Anderson, C., & Walsh, I. (2020). Research-based internet writing projects in the Russian curriculum. In E. Dengub, I. Dubinina, & J. Merrill (Eds.), The art of teaching Russian (pp. 431–454). Georgetown University Press.

Arens, K., & Swaffar, J. K. (2005). Remapping the foreign language curriculum: An approach through multiple literacies. Modern Language Association of America.

Byram, M. (2020). Teaching and assessing intercultural communicative competence: Revisited. Channel View Publications.

Carbonneau, S., & Fournier, M. (n.d.). Manie musicale. https://www.maniemusicale.info/bienvenue

Etkind, A. (2013). Internal colonization: Russia’s imperial experience. John Wiley & Sons.

Garza, T. J. (2021). Here, there, and elsewhere: Reimagining Russian language and culture course syllabi for social justice. Russian Language Journal, 71(3), 41–63. https://doi.org/10.26067/F8PA-W125

García, O., & Wei, L. (2014). Translanguaging: Language, bilingualism and education. Palgrave Macmillan Pivot.

Karkour, I. (2022). Intercultural competence in elementary-level language classes in higher education. In E. Nemtchinova (Ed.), Enhancing beginner-level foreign language education for adult learners: Language instruction, intercultural competence, technology, and assessment (pp. 95–112). Taylor & Francis.

Kassymbekova, B. (2023, January 24). How Western scholars overlooked Russian imperialism. Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2023/1/24/how-western-scholars-overlooked-russian-imperialism

Kimura, D., & Tsai, A. (2023). Decolonizing classroom discourse: Insights from interactional research. ELT Journal, 77(3), 327–337. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccad008

Kokotsaki, D., Menzies, V., & Wiggins, A. (2016). Project-based learning: A review of the literature. Improving Schools, 19(3), 267–277. https://doi.org/10.1177/1365480216659733

Kumaravadivelu, B. (2001). Toward a postmethod pedagogy. TESOL Quarterly, 35(4), 537–560. https://doi.org/10.2307/3588427

Lenin, V. I. (1920). Letter to the workers and peasants of Ukraine, apropos the victories over Denikin. In Collected works (Vol. 30, pp. 291–297). Progress Publishers. (Original work published 1920)

Liddicoat, A. J., & Scarino, A. (2013). Intercultural language teaching and learning. John Wiley & Sons.

Macedo, D. (Ed.). (2019). Decolonizing foreign language education: The misteaching of English and other colonial languages. Routledge.

National Standards Collaborative Board. (2015). World-readiness standards for learning languages (4th ed.). https://www.actfl.org/publications/all/world-readiness-standards-learning-languages

Nemtchinova, E. (2020). Developing intercultural competence in a Russian language class. In E. Dengub, I. Dubinina, & J. Merrill (Eds.), The art of teaching Russian (pp. 333–358). Georgetown University Press.

Norton, B., & Toohey, K. (Eds.). (2004). Critical pedagogies and language learning. Cambridge University Press.

Nuss, S., & Kogan, V. (Eds.). (2023). Dynamic teaching of Russian: Games and gamification of learning. Routledge.

Prince, T. (2023, January 1). Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine triggers ‘soul-searching’ at Western universities as scholars rethink Russian studies. Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. https://www.rferl.org/a/russia-war-ukraine-western-academia/32201630.html

Snowball, J. D., & McKenna, S. (2017). Student-generated content: An approach to harnessing the power of diversity in higher education. Teaching in Higher Education, 22(5), 604–618. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2016.1273205

Suny, R. G. (1995). Ambiguous categories: States, empires and nations. Post-Soviet Affairs, 11(2), 185–196.

Tochon, F. V. (2019). Decolonizing world language education: Toward multilingualism. In D. Macedo (Ed.), Decolonizing foreign language education (pp. 264–281). Routledge.

Zhang, Y., & Wei, R. (2021). Strategic use of L1 in Chinese EMI classrooms: A translanguaging perspective. In W. Tsou & W. Baker (Eds.), English-medium instruction translanguaging practices in Asia: Theories, frameworks and implementation in higher education (pp. 101–118). Springer.