A Click Away: Lessons Learned after Four Semesters of Virtual Exchange Program Experience for Intensive Beginning-Level Spanish Learners

By Lourdes Sabé, Yale University

DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.69732/DJFB8847

This article describes the culmination of a four-semester implementation of an e-tandem virtual exchange (VE) program between beginning-level Spanish language students at a US university and undergraduate students at a Peruvian university in the fall semesters from 2020 to 2024. This piece reflects on the feasibility of implementing a VE program at the intensive beginning-level, assesses its partnership with the Peruvian institution, and shares and discusses the US students’ perceptions of their gains based on their feedback about the experience.

Introduction

Learning a language has never been easier and more accessible than today. Exposing learners to native speakers of the target language can be an engaging, highly effective, and interactive way to increase proficiency. The possibilities with today’s technology are almost endless, facilitating the boom of VE programs as an essential component of many language programs around the world, allowing people to interact across cultural borders (Taskiran, 2019). Video communication tools (such as Zoom, Teams, Skype, and Facetime) facilitate communication with native speakers, which can be an absolute game-changer. By doing so, students can immerse themselves in the language in ways classroom settings alone cannot offer.

As a language instructor, I welcome these technologies and opportunities into the classroom whenever possible, even at the elementary level. But participating in VE programs is especially difficult at the novice level. Novice level learners struggle with basic vocabulary and grammar, especially when trying to communicate orally, which can lead to difficulties in understanding and being understood. Their fear of making mistakes and the stress of real-time communication with a native speaker are very real. This can cause some students to hesitate in engaging actively and may inhibit participation and conversational flow. Other challenges such as understanding different cultural norms (addressing formally or informally, taking turns for speaking, body language, gestures, facial expressions, etc.) or managing technology are also important obstacles. However, in these four years of the implementation of the VE program in the intensive Spanish class I have witnessed how most students overcome these challenges with careful preparation, a positive attitude, and by welcoming linguistic mistakes as opportunities to learn from them. Before the VE program begins in the 7th week of the semester, students have had many opportunities to role-play in the classroom, they have conversed one-on-one with their instructor and done some VE preparation sessions and reflection in the classroom prior to conversing with their Peruvian counterparts. The topics of discussion and tasks of the VE sessions are familiar to the US students, which helps them feel less anxious, particularly in the first of the five sessions. As US and Peruvian students get to know each other, the following conversations become more natural, resulting in more confidence as the program progresses. Although this intensive Spanish class welcomes any students interested in learning the language (both true and false beginners), the group composition is different from the regular Spanish class in my institution. Given its fast pace, this course attracts students with a background in Spanish or in other Romance languages, and highly motivated undergraduate, graduate or students in the professional schools. Because of the distinct nature of the intensive group, I wanted to investigate whether VE could be successful even at the elementary level.

As mentioned, the VE program allowed for real-time conversations, giving learners opportunities to meet with native speakers who can potentially become a sort of a personal language coach and cultural guide rolled into one, helping the students work toward communicative and cultural competence. Researchers agree that learners must have contact with non-native cultures and intercultural interactions in the target language in order to make progress toward achieving intercultural communicative competence (McCloskey, 2012).

Logistics

You may be wondering: how can you start a solid VE program? How can you find and establish a robust university-setting partnership? One way to start is by identifying universities with active international offices interested in establishing new partnerships or with existing international exchange networks, as well as utilizing connections and collaborations that faculty members may already have. Alternatively, a well known online platform for finding partnerships, providing training, and exploring VE is UNICollaboration, a cross-disciplinary professional organization committed to promoting the development and integration of Virtual Exchange.

One of the language courses I teach annually is intensive elementary Spanish. This course follows a 4/1 meeting pattern, meeting four times a week synchronously for about two hours (two 50-minute sessions into one) and one asynchronous day. Asynchronous days allow for students to engage with course materials and activities on their own schedule and at their own pace, managing their time and responsibilities more autonomously. This 4/1 meeting pattern was implemented in this class after the pandemic, and the flexibility of the asynchronous day allowed students to freely schedule their VE sessions.

The students enrolled in this intensive class represent a different population of students than those in regular classes, with a strong presence of older students–undergraduate students in their fourth year, graduate and professional school students (Medical School, Law School, School of Management, etc.), and working professionals. Their interests also go beyond simply learning the language, including a keen interest in the linguistic aspects of the language in relation to Latin or other Romance languages (e.g. French, Italian, Portuguese, etc.) as well as cultural aspects, and many of them seek exposure to authentic texts and contexts to make the learning more meaningful.

Structure of the Program

I was interested in seeing if a tandem VE program could enhance the course if tailored to the level and the needs of my intensive Spanish learners. Its basic structure consisted of five sessions of thirty minutes each, half the time (fifteen minutes approximately) in Spanish and the other half in English. The participation in the project of Peruvian students was on a voluntary basis, while for the US students it was a mandatory component of the course, making up 10% of the course grade. At the end of the program all students were invited to complete a survey to share their views on the benefits and challenges of the program as well as to provide suggestions and ways to improve it. This was implemented during four fall semesters at the US institution, from 2021-2024. The program begins in the first half of October, roughly at the mid-point of the semester, so that students have some facility with the language before the first meeting.

Topics are provided by the instructor in the first three exchange sessions, based on the curriculum covered in class prior to the meetings. For the fourth meeting, students may choose the topic or topics of their choice from a list provided by the instructor but based on successful topics in previous years. For the fifth semester the students may choose their own topic. After each conversation, the students at the US institution are required to write a short report (in English after the first two exchanges, but in Spanish the remaining three) documenting what they learned both linguistically and culturally in each session as well as sharing the challenges of the experience. Reports one, three and five are posted and shared among the students in the US in the Learning Management System (LMS) for the Spanish course (we used a Canvas Discussion Forum) and students are required to also post a short reflection on one of their peer’s reports. Having the students read each other’s posts opens a stimulating exchange in which classmates learn about each other’s experiences in these three VE sessions, sharing challenges and successes among them. When preparing reports, students are asked to use WordReference (or similar) but to avoid the use of online translators or AI.

After each conversation has taken place (five in total), students are required to upload the video recording and to submit a brief report that serves as a reflection on linguistic and cultural aspects learned in each conversation. US students receive feedback from the teacher and a low stakes assessment on both the report and the virtual conversation. Although students in Peru are not assigned written homework or receive grades for each session or their overall participation in the VE program, it is expected that Peruvian students carefully prepare for each session.

Overall, the program allows students to take agency in their learning by having autonomy over some aspects of the sessions (scheduling day/time, determining some of the discussion topics, extending the length of the session beyond the minimum, etc.). All participants are both learners and teachers, as they depend on and help each other in the linguistic and intercultural collaboration endeavor. Although there are only five sessions throughout the semester, the students must prepare for each conversation (e. g. write a few questions for their partner in Peru, review and prepare basic vocabulary on the topic), reflect about each interaction from a linguistic and cultural perspective, and complete and submit a written reflection piece or report for each meeting. The fact that all sessions are half in English and half in Spanish also helps them get to know and bond with their partner, reinforcing the value of learning to communicate in another language. This makes for a lasting impact on their ability to speak in Spanish.

But what do Peruvian students get out of this VE experience? Despite the fact that their participation in the program does not grant students abroad formal academic credit, students benefit from the intellectual exchange of experiences with college students in the US, and it allows them to make connections with peers from universities abroad, offering them an opportunity to practice their English speaking skills with native or near-native English speakers. It also broadens their cultural understanding and perspectives, and at the end of the program, Peruvian students receive an official letter confirming their participation. Taking part in the program is valued in their applications into a graduate program, for instance, or in demonstrating English proficiency to potential employers.

Development of the VE Program

The VE program had the following design stages of development:

Step 1. Once I identified the university abroad with active international programs and verified with the appropriate person(s) and Department of mutual interest in creating a new VE program, I worked closely with their Department of International Division (in Peru) to set the protocol and its requirements. After that, there was a search for Peruvian students in the university in Lima interested in enrolling. The application process included an individual interview between each Peruvian student and the Head of the Academic Office of Institutional Affairs. This was done to determine the best suited participants and to clarify any questions the Peruvian candidate may have had. This phase of the program required a great deal of time from the Head of the Academic Office of Institutional Affairs of the institution abroad because the VE program had a large number of applications from Peruvian students. Particularly in 2020, the first year in which this inter-institutional program was offered, there was an overwhelming number of Peruvian students applying due to the pandemic. In 2021-2022 the university in Lima only offered online classes and students were still under some degree of isolation, while at our institution classes had returned to being in person.

Applicants interested in participating in the VE program must abide by the following requirements:

- Have availability and flexibility to schedule five online sessions (dates provided by the instructor).

- Have a commitment to the program (e.g. preparing each session, responding quickly to messages, providing any requested materials, and attending the orientation meeting conducted by the instructor and an informal presentation session with the US students, if possible).

- Have access to reliable internet and the necessary technological tools, preferably Zoom, and a quiet space where the sessions could take place.

Step 2. As part of the selection process, there was an individual interview between Peruvian applicants and the international program’s office. The group of students selected then met virtually with the instructor to receive additional information on the goals and guidelines of the program, to pose and answer questions, and to clarify any aspects about the VE program students may have.

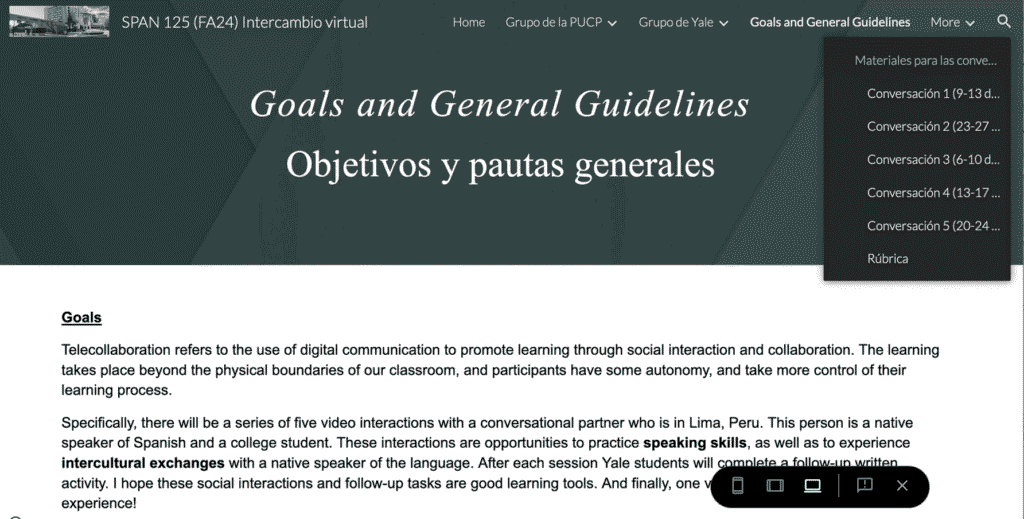

Step 3. A Google Site is created each year to compile all the important aspects of the program on one virtual platform that makes it accessible to all participants.

Creating the website demands a great deal of time. The information on the website includes:

1. Goals of the program and program guidelines.

2. Detailed instructions for each VE session: scheduling, topic(s), how to prepare, and post-conversation tasks. The scheduling information indicates the window of time in which the sessions should take place (usually about 4-5 days). Regarding the topics, these are based on material previously covered in class, so the sessions are opportunities to practice with a native speaker what students in the US have studied and practiced in class. Below are the topics/tasks, suggestions on how to prepare the sessions, and reports. The “Reports” column applies only to students in the US:

| Topic(s) or tasks | How to prepare | Reports | |

| Session 1 | Introductions. Basic information exchange. | How will I address my partner? (informal ‘tú’/formal ‘usted’) How will I introduce myself? What do I want to know about my partner? How do I ask my partner to repeat something, to speak slower/ louder, type in the Chat, etc.? | Write a report in English of 200-250 words reflecting on your linguistic and/or cultural experience. Are your lives very different?

Post the report in the LMS Discussion Forum (Canvas). |

| Session 2 | Our universities. Describe your university. Use Google Earth (or similar) to show an aerial view of the campus. | Prepare basic information about your institution. Prepare at least five questions about your partner’s university. | Write a report in English of 200-250 words including the questions you prepared and mention a cultural aspect you have learned. What did you like or what surprised you about the Peruvian university? Why? |

| Session 3 | A day in the city.

Both students are visiting each other’s hometown/ university for one day and both must prepare an itinerary. There is a budget of $50 or 190 soles (Peruvian currency)!

|

Find basic information about the city/state. Prepare a few questions for your partner about Lima. Prepare and present an itinerary with images you can share on Zoom. Explain why you picked those places and be mindful of the budget! | I. Write a report in Spanish of 100-120 words reflecting on the following: What was challenging about this task? Mention an interesting element of the itinerary in Lima, and a linguistic and/or cultural aspect you learned.

Post the report in the LMS Discussion Forum (Canvas). II. Briefly comment on one entry of your peers (Canvas). |

| Session 4 | Option 1. For the next session, please select among these topics: environment, families, food, health, hobbies, jobs, music, sports, and travel.

Option 2. Describe a tradition/celebration observed in your family, town or country. |

Prepare the vocabulary needed to discuss the topic(s) of your choice. Write a few questions beforehand to ask your partner. | Record a 2/3-minute voice recording in Spanish with the questions you prepared and a reflection on linguistic and/or cultural aspects you learned.

If you picked option 2, please compare both celebrations. |

| Session 5 | Free-form. Students choose their own topic(s) of discussion. | Prepare the topic(s) of discussion by doing some research on them. For international current news you may use https://es.kiosko.net/ | I. Write a report in Spanish answering some of these questions: What did you talk about? Do you prefer to have topics assigned or free-form sessions? What were the most challenging and gratifying aspects of the VE program?

Post the report in the LMS Discussion Forum (Canvas). II. Briefly comment on one entry of your peers (Canvas). |

3. The Google Site also includes brief bios of all students, in English for students in the US and in Spanish for Peruvian students. Students are invited to read these personal narratives and to request a virtual partner. The Google Site is also meant to encourage a sense of community by posting virtual group pictures of the students involved in the program.

4. Rubric. The VE program is 10% of the course grade, and although it is conceived as a low-stakes component of the course it does require preparation, active participation, and reflection, especially from the students in the US institution. The rubric provides the main criteria in which students will be marked for each session: I. Preparation, engagement, and content (75%), II. Communication (10%), III. Grammar and structure (10%), IV. Vocabulary (5%). Students are welcome to make suggestions about the rubric.

Step 4. Virtual gathering of all participants of both universities. Before the beginning of the VE sessions in week 7 of the academic calendar, I scheduled a Zoom meeting for all students to start getting to know each other.

The five conversational sessions take place in pairs and are scheduled during weeks seven, nine, eleven and thirteen of the fall academic calendar at the US institution and are video recorded. The recording of the sessions is a way for the instructor to make sure that the technology and the settings are appropriate for the successful outcomes of the project. It allows me to provide students with positive reinforcement, or to clarify any aspects that need addressing based on the recorded sessions. I find this to be particularly useful after the first session.

The first conversation takes place on week seven, which corresponds to the beginning of the second half of the semester, when students have some basic linguistic tools to convey uncomplicated information and ask and answer simple questions. By the end of the semester learners of Spanish should reach the Intermediate-Mid level, being able to successfully handle basic communication on familiar topics, and engage effectively in predictable exchanges involving personal information, among other abilities.

The topics of discussion and all prompts are in alignment with the proficiency level of the Spanish learners at this point, Intermediate Low in the ACTFL scale at the beginning of the VE program. The English learners have a higher proficiency in English than the Spanish learners in Spanish.

Step 5. After the five interactions, both US students and students abroad provided feedback on the experience. Participating students abroad received a Certificate of Participation letter.

Students’ Feedback

At the end of each VE program, students in the US were asked to provide anonymous feedback via a survey about their views on the effectiveness of the program. The survey asks if they have the perception of having reached their linguistic and cultural goals, what in their view were the major benefits and challenges of the program, as well as any suggestions on how to improve it. The following common themes have been extracted from the surveys of a total of 41 students:

| Perceived benefits by students in the US university | Challenges indicated by students in the US university | Implemented suggestions made by students in the US university |

| Speaking practice. Good opportunities to practice casual conversational Spanish. Allows for speaking practice in a more natural and authentic way.

|

Listening comprehension. Listening comprehension difficulties due to native speaker’s pace, accent, vocalization, topic, vocabulary/ structures, sound quality, etc. | Recordings. Mandatory recording of the Spanish part of the conversation only (about half the session.) |

| Travel. Interest in visiting Peru. | Vocabulary. Limited vocabulary to get the ideas across in Spanish. | Reports. Shorter follow-up writing assignments. The first two reports can be submitted in English to allow more time to prepare for the session. |

| Study abroad. Increased and maintained interest in study abroad. | Technology issues. Occasional difficulties connecting over Zoom and recording the sessions. | Scheduling of the conversations. More flexibility. From having three days to one week to complete the assignment, report included. |

| Fluency. Noticeable increase in fluency by the end of the program. | Time. Keeping track of time (~30’ total) and the balance of the conversation (50% Spanish – 50% English.) | Topics. Multiple topics in one session, and wider selection of topics for session four. |

| Culture. Allows for cultural engagement in a natural way. | Scheduling. Finding the right day/time for both students can be difficult. There is also a one-hour time difference for the first half of the program. | Guidance. More guidelines to Peruvian students to keep the language accessible to beginner-level Spanish learners.

|

| Optional. Allowing pairs to meet up. |

Students’ survey responses have been crucial for me to understand how to enhance all students’ virtual exchange (VE) program experiences. Based on their input, I have applied many of the suggestions made. For instance, to make scheduling more flexible, students now have a longer period to schedule their conversation, which went from 2-3 days to almost a week. Also, to assist students with Spanish listening comprehension and vocabulary challenges, I have added more classroom time to prepare for the VE sessions, including brainstorming the topics and exposure to the Peruvian accent. Now students record only the Spanish part of the conversation, or only the first fifteen minutes of the Spanish part of their conversation if it goes beyond the fifteen minutes time. This makes students feel more at ease. Additionally, if students wish to have pair meet ups or propose other topics, this is not only possible but encouraged. Lastly, students have more time to submit their reports, and the first two reports (rather than only the first one) can be submitted in both English and Spanish. When student suggestions were in opposition to other views expressed by peers no changes were made. For instance, a few students indicated that more than 5 sessions and/or longer than 30 minutes would be preferable, but more have expressed satisfaction with the number of sessions and the length. Extending the sessions can be done on a voluntary basis.

Takeaways

The e-tandem VE program between US university students and college students in Peru showed some consistent results. Overall, the students were significantly more excited about studying abroad and learning about Peruvian culture after the VE program. Participants in the intensive elementary Spanish indicated their perceptions on the outcomes of the program, pointing to noticeable improvements in speaking, listening, and conversational abilities by the end of the program. In the second half of the VE program, after their third and fourth conversational meeting, I observed that the Spanish learners were more at ease, not only in their VE sessions, but also in the classroom. There was an increase in their willingness to participate in exercises that involve speaking, from simple warm up questions to activities in small groups using Spanish as the sole language of communication, reporting the findings of an activity and answering questions about it (interpersonal and presentational formats), and at the same time I observed more self-correction. Obviously, to a large degree it is to be expected that as the semester progresses in an intensive class that meets about two hours a day for five days, students will show steady progress on their language abilities, but I noticed that Spanish became more real to them, a bit less foreign after this personal experience. Culturally, students report an increased interest in cultural aspects learned from their Peruvian interlocutors and how this exposure has sparked the sense of continuing to learn more about these and other cultural aspects.

The feedback also pointed out the importance of encouraging better preparation from both parties, particularly from Peruvian students who are not enrolled in the VE program for college credit, but rather to connect with US college students, practice their conversational English skills with a native or near-native speaker, and to share and learn cultural and personal experiences with their counterparts. Now I am more proactive about reaching out to students abroad who do not seem as committed as they should be to ensure that their participation is meaningful and effective and to assist them in any way necessary. Currently, I keep a waiting list with a couple of Peruvian students who are willing to join the program but were not selected initially, in case a change of a partner abroad is needed for any reason.

Student comments showed how valuable the real-time conversational practice and cultural exchange can be, even though they mentioned their difficulties in communicating with spontaneity and limited vocabulary. These insights highlight the program’s positive impact on language skills and cultural engagement, while also pointing out ways we can improve logistics and support for beginner-level learners, in this case, intensive beginners.

In the booming age of Artificial Intelligence, I find the VE program even more relevant today than ever because it allows both instructors and students alike to see what students can do with the language in an unrehearsed, authentic, and meaningful way, human to human. It is an experience that is just a click away, but is one that they will never forget!

References

Katsnelson, J. (2024) If you can’t go to Russia, Russia will come to you – direct communication with native speakers: Oral and written practicum projects. The FLTMAG (July 2024). https://www.doi.org/10.69732/QNGV1410

O’Dowd, R., & Ritter, M. (2006). Understanding and working with ‘failed communication’ in telecollaborative exchanges. CALICO Journal, 23(3), 623-642. DOI:10.1558/cj.v23i3.623-642

McCloskey, E. M. (2012). Global teachers: A model for building teachers’ intercultural competence online. Dossier.https://doi.org/10.3916/C38-2012-02-04

Taskiran, A. (2019). Telecollaboration: Fostering foreign language learning at a distance. Siendo European Journal of Open, Distance, and e-Learning, 22(2), 86-96. DOI:10.2478/eurodl-2019-0012