Chatbots From Classroom to Conference: Fostering Collaboration in Language Learning with Mizou

By Carmen De Lorenzo, Michigan State University, and Silvia Giorgini-Althoen, Wayne State University

DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.69732/LJOQ6934

Introduction

Language teachers today are moving beyond initial experimentation with AI toward intentionally designing student-centered learning experiences that reflect their pedagogical values, creativity, and goals. For us, this journey began with an initial experiment using Mizou, a free educational AI chatbot platform, in our own classrooms. As we reflected on that experience, we began to design activities more deliberately, grounding them in our teaching philosophies and in students’ creative work. We later shared this process with other educators during a session at The Michigan World Language Association (MIWLA) conference, From Classroom to Chatbot: Reimagining Language Teaching with AI, where we invited participants to build chatbots inspired by student work from several of our courses.

In this article, we share how we used Mizou not simply to introduce a new AI tool, but to design student-centered writing activities with clear pedagogical intentions. We then adapted those same activity-design strategies for professional development with teachers, focusing on how to plan meaningful learning experiences rather than on the technical features of the platform itself. What began as a small classroom experiment became a collaborative exploration of how AI can support communication, creativity, and reflection, without losing the human connection at the heart of language learning.

From Theory to Practice

Much has already been said about the growing presence of AI in education, especially around personalization, student engagement, and new possibilities for access, as noted by Deckker and Sumanasekara (2025). In our own teaching contexts, these conversations resonate most when they move beyond abstract potential to focus on what actually happens when AI tools are implemented in the classroom: how students respond, how they stay motivated, and how the design of tasks shapes the quality of their interaction, a shift also emphasized in classroom-based research by Huang et al. (2022).

In conversations with colleagues and students, as well as in our own classrooms, one idea keeps resurfacing: AI is only as useful as the “human” tasks built around it. This insight echoes what many educators and researchers have noted in recent work on AI and language learning, including Spirydovich (2025) and Wiboolyasarin et al. (2025), who point to the importance of framing, questioning, and disciplinary context. For us, working across language, literature, and culinary history means designing structured, historically grounded tasks that invite students to engage with content not as static material, but as lived and imaginative worlds.

It was from this perspective that we turned to Mizou. Rather than starting with the tool itself, we began with the kinds of thinking, interaction, and creativity we wanted to support. In the sections that follow, we share how Mizou helped us bring those goals together by supporting interdisciplinary thinking, historical imagination, and communicative fluency.

What is Mizou, and Why Now?

Mizou is an AI platform designed for classroom use. From a practical standpoint, it fits our courses well: students do not need to create accounts, and activities can be launched simply by sharing a link. This made it easier to integrate AI into regular coursework without adding technical difficulty for students or instructors.

More importantly, Mizou helped us address a recurring instructional concern in our courses: how to offer students space for individualized interaction while still maintaining clear guidance and shared expectations. As others have noted in discussions of responsible classroom uses of AI (e.g., Deckker & Sumnersaker, 2025), the way instructors frame and scaffold the instructions given to AI tools, together with attention to accessibility, is essential. In practice, the AI-mediated activities we designed encouraged students to explore ideas and language independently, while still operating within clearly framed and shared expectations. Importantly, our focus was not on adopting a new technology, but on designing tasks in which AI could support intentional pedagogical goals without displacing instructor guidance or student reflection.

Mizou also includes a paid feature, the “Knowledge File”, that allows instructors to upload course materials to shape chatbot responses. While we worked primarily with the free version, we see this feature as a useful option to further ground AI interactions within course-specific texts and contexts (as of early 2026, the individual plan costs $12.90/month).

Across our courses, Mizou’s multilingual and privacy-conscious design aligned well with our needs. In practice, students often wrote more and focused more on meaning rather than on formal correctness, which ultimately led to interactions that felt more sustained and engaged. These outcomes were not accidental, but closely tied to how the tasks were framed, scaffolded, and positioned as low-stakes spaces for exploration.

How We Used It in Our Courses

Previous studies, including work by Huang et al. (2022) and Wiboolyasarin et al. (2025), often examine AI use in second-language acquisition, where the focus is on communicative fluency, linguistic development, and learner motivation. While our work resonates with these findings, we were also curious about what might happen when a chatbot is used in a different instructional context, one not centered primarily on language learning.

Mizou in a Content-Based Culinary History Course

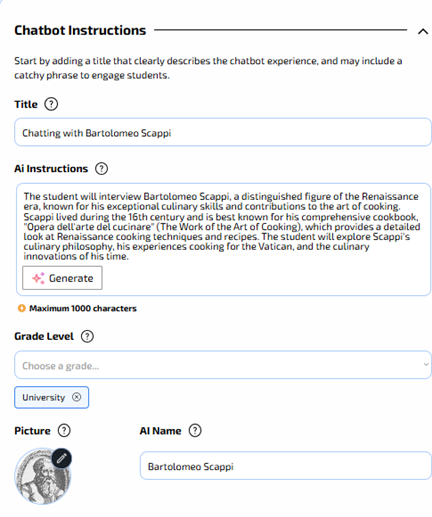

Silvia first implemented Mizou in a content-based culinary history course taught in English. In this context, the chatbot was used as part of a structured assignment in which students engaged the Scappi persona (an AI avatar based on Bartolomeo Scappi, a celebrity Papal chef of the Renaissance) through a historical interview. Students prepared questions and conducted a sustained back-and-forth response exchange, during which they explored Scappi’s works (his most famous work is called Opera dell’arte del cucinare), culinary practices, personal experiences, and the relationship between historical and contemporary cooking.

To guide the interaction, Silvia authored instructions that shaped student engagement, defined the chatbot “Bartolomeo Scappi” as a culinary expert from the Renaissance period, and shaped how students would engage with him. Students were invited to “interview” Scappi through an introductory welcome message that emphasized immersion in sixteenth-century cuisine and culinary culture. The chatbot was instructed to respond only from historically plausible perspectives, to avoid modern references, and to guide students through follow-up questions rather than authoritative answers. Together, these elements positioned the chatbot as a conversational guide supporting curiosity, interpretation, and historically informed inquiry. Students submitted their completed interactions through the course learning management system for completion credit, with expectations focused on critical engagement and sustained inquiry rather than factual accuracy.

As illustrated in the table below, this design encouraged extended exchanges in which students pursued lines of questioning over multiple turns. Rather than providing definitive answers, the chatbot consistently redirected the interaction through follow-up questions, prompting reflection, interpretation, and historical reasoning within Renaissance culinary contexts. These exchanges help explain the forms of student engagement discussed below.

The following excerpt illustrates how students engaged the Scappi chatbot through multi-turn dialogue, using questioning and reflection to explore historical culinary practices.

| Persona | Conversation |

| 🧑🎓 Student | Hello Scappi, I’m curious – a lot of your recipes from your cookbook are from differing locations or pull from inspiration found in other regions. How or where did you source this information and knowledge? |

| 👨🍳 Scappi (chatbot) | My culinary repertoire is indeed a tapestry woven from various influences. I traveled extensively, absorbing techniques and flavors from regional kitchens across Italy and beyond. I also engaged with other cooks, learning from their traditions and experiences. Observation was crucial; I studied markets, ingredients, and the cultural practices surrounding food. My interactions with nobles and the Vatican also refined my understanding of presentation and taste. How do you believe these diverse influences shaped the culinary landscape of the Renaissance? |

| 🧑🎓 Student | I think those diverse influences brought a sense of richness and innovation to Renaissance cooking. As chefs like you traveled and shared knowledge, regional barriers began to blur, and a more unified yet creatively varied culinary identity emerged. What did a typical day in a Renaissance kitchen look like under your supervision? |

| 👨🍳 Scappi (chatbot) | You capture the essence beautifully! A typical day in my kitchen was a symphony of activity. Early mornings would begin with gathering fresh ingredients from markets or gardens, followed by meticulous preparations. My staff and I would organize tasks: some would tend to meats, others to vegetables or pastries. Precision and artistry were paramount; we aimed to please both the palate and the eyes. We prepared numerous dishes for feasts—each a showcase of flavors, techniques, and creativity. It was a demanding environment, yet filled with camaraderie and a shared passion for excellence. What specific dish or technique intrigues you about Renaissance cooking? |

| 🧑🎓 Student | One dish that really intrigues me is your version of tortelli—especially how it blends sweet and savory with ingredients like cheese, herbs, and sometimes even sugar or cinnamon. That combination feels bold compared to modern expectations. What do you hope people learn or take away from “Opera” today? |

| 👨🍳 Scappi (chatbot) | Ah, tortelli! A delightful example of how Renaissance cooking embraces contrasts! My hope for readers of “Opera dell’arte del cucinare” is to appreciate the artistry behind every dish—the balance of flavors, the importance of seasonality, and the creativity in combining sweet and savory.

Food is not merely sustenance; it communicates culture and tradition. I encourage today’s chefs to explore bold combinations and remain fearless in their culinary explorations, much like we did during my time. How do you think the blending of flavors influences modern cuisine today? |

| 🧑🎓 Student | I think the blending of flavors is at the heart of what makes modern cuisine so exciting. With global access to ingredients and techniques, chefs today are constantly experimenting—mixing sweet with heat, sour with umami, or blending cultural traditions to create something entirely new. Did you see this practice happening during the Renaissance? |

| 👨🍳 Scappi (chatbot) | Indeed! Even in the Renaissance, we embraced experimentation and the fusion of flavors. As trade routes expanded, exotic ingredients and spices became available to us, inspiring creativity in the kitchen. Chefs of my time, including myself, often mixed regional specialties, drawing from the diverse influences of Italy and further afield.

This blending of flavors was not just practical but also artistic; it was a way to showcase wealth and sophistication at banquets. I see parallels in your modern practices, and it excites me to think of culinary evolution. |

In practice, the chatbot’s responses were generally accurate and historically plausible. The combination of the model’s underlying knowledge and the teacher-authored persona instructions helped anchor responses to the historical figure and context, limiting anachronistic or generic replies.

Students felt it was meaningful to “speak” with experts from previous generations, while at the same time they demonstrated an awareness that the chatbot represented a historically grounded simulation rather than a direct historical voice, recognizing the instructor’s role in framing the persona and its limits. Some thought that this dialogue felt more memorable and engaging than traditional peer discussion.

Italian Literature and AI

Shifting from historical imagination to linguistic production, later Silvia implemented Mizou in an Italian literature course taught entirely in Italian. While the disciplinary focus shifted, the underlying design principles, i.e. intentional framing, sustained dialogue, and low-stakes exploration, remained consistent. In this context, students completed a structured conversational assignment in which they engaged with Italian literary figures such as Dante, Petrarch, Boccaccio, Machiavelli, and Ariosto. Students posed interpretive questions in Italian, responded to the chatbot’s prompts, and sustained dialogues in order to articulate ideas and clarify meaning. Students submitted their interactions through the course learning management system for completion credit within a labor-based grading framework.

This activity supported linguistic production while also fostering register awareness, stylistic choice, and textual interpretation. Working in a low-stakes communicative space, students wrote more freely, took linguistic risks, and sustained dialogue beyond what they might typically produce in class.

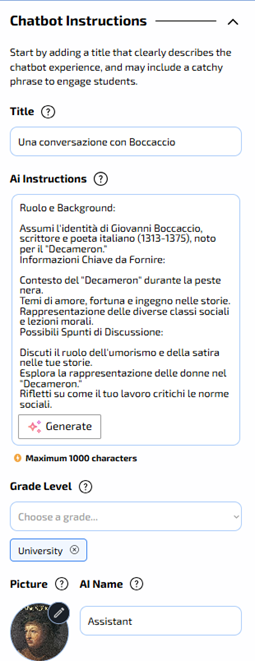

For example, in one assignment, students interacted with the Italian writer Giovanni Boccaccio. The chatbot was designed with instructions written in Italian establishing Boccaccio’s historical identity, situating the exchange within Boccaccio’s collection of short stories called The Decameron, and foregrounding themes such as love, fortune, ingenuity, and social critique. In this Italian-language implementation of Mizou, the chatbot responded in ways that were broadly consistent with Boccaccio’s literary voice and historical context. While responses occasionally simplified complex ideas, the chatbot avoided anachronistic references and remained anchored in themes, tone, and perspectives drawn from The Decameron.

|

|

|

Students engaged in sustained dialogue in Italian by advancing interpretive claims and responding to scaffolded follow-up questions generated by the chatbot. Although some student responses were not fully idiomatic or grammatically accurate, their language remained communicatively effective and demonstrated students’ willingness to take linguistic risks, experiment with abstract vocabulary, and extend syntactic complexity.

Across similar exchanges, the chatbot’s design encouraged iterative meaning-making rather than single-turn responses, supporting extended engagement with literary content in Italian. Some students expressed that working with Mizou was the highlight of their learning process and found it very meaningful, as it included learning and analysis, but also play, allowing creativity and risk-taking.

Chatbots in an Italian Language Class

Carmen adopted Mizou in a more explicitly language-focused context. In her Italian (ITL) 320 Advanced Grammar and Composition course, she provided the chatbot with teacher-authored instructions that positioned Guglielmo Marconi (the inventor of the telegraph) as an inquisitive historical interlocutor, rather than a source of factual information.

The chatbot design prompted students to practice the Italian imperative by responding to Marconi’s repeated requests for instructions related to modern technologies. Through instructor-defined interaction rules and an initial welcome message that set expectations for dialogue, the chatbot supported sustained interaction in Italian, encouraging students to expand their responses, clarify meaning, and maintain extended conversations over multiple turns.

The chatbot activity was done in class. After targeted vocabulary and grammar preparation, Carmen introduced the activity with a short biographical reading on Guglielmo Marconi and three scaffolded cultural and lexical tasks. At that point, she invited students to engage in the in-class activity (“Adesso che lo conoscete meglio, parliamo con Guglielmo Marconi!” / Now that you know him better, let’s talk with Guglielmo Marconi), in which she introduced the chatbot as a conversational partner rather than an information source. Students interacted with “Marconi” in Italian, by responding to his prompts using the imperative and by providing more information when he requested clarification or greater specificity. Rather than moving quickly from one question to the next, students worked within a single exchange, expanding, reformulating, and refining their instructions over multiple responses.

This structure led to extended written exchanges. Several students commented that they felt free to write without judgment and appreciated being able to take their time formulating responses. Others noted that Marconi’s repeated requests for clarification pushed them to be more precise and reduced their reliance on translation tools.

Throughout the activity, grammatical accuracy emerged through repetition and reformulation rather than direct correction. Students remained in dialogue long enough to notice when their instructions were incomplete or ambiguous and modified them accordingly. Because the interaction unfolded over multiple turns and without immediate evaluative feedback, students had time to experiment, revise, and re-enter the conversation without penalty. This iterative process helps explain why students reported greater confidence and why the activity supported more inclusive participation, particularly for those who benefit from having time and space to revise their written Italian.

Sample Student–Chatbot Exchange

| Persona | Italian (original wording) | English (meaning-based translation) |

| Marconi

(chatbot) |

Salve! Sono Guglielmo Marconi. Io sono l’inventore del telegrafo, ma non conosco le invenzioni moderne. Dimmi come si usa uno smartphone: guidami passo per passo. Come funziona? | Hello! I am Guglielmo Marconi. I am the inventor of the telegraph, but I do not know modern inventions. Tell me how to use a smartphone: guide me step by step. How does it work? |

| Student | Ciao, piacere di conoscerti. Allora lo smartphone è troppo utile, lo usano ogni giorno e non solo come strumento, ma anche per comunicare con qualcuno in qualunque parte del mondo. | Hi, nice to meet you. So, the smartphone is very useful; people use it every day, not only as a tool, but also to communicate with someone anywhere in the world. |

| Marconi

(chatbot) |

Molto interessante, davvero! Ora spiegami come inviare un messaggio su WhatsApp. Quali sono i passaggi? | Very interesting, indeed! Now explain to me how to send a message on WhatsApp. What are the steps? |

| Student | Prima, apri il tuo smartphone e trova WhatsApp. Poi, scrivi un messaggio con la tastiera. | First, open your smartphone and find WhatsApp. Then write a message using the keyboard. |

| Marconi

(chatbot) |

Ottimo! Dopo aver scritto il messaggio, che cosa devo fare per inviarlo? Spiegami il passaggio, per favore. | Excellent! After writing the message, what do I need to do to send it? Explain the steps, please. |

| Student | Allora devi cliccare il pulsante “invia” (di solito è verde) e il messaggio arriva alla persona. | Then you have to click the “send” button (it is usually green), and the message reaches the person. |

Across all three courses, this iterative dynamic became a shared and important element of the activity. Students did not simply receive chatbot replies; instead, they learned to shape the interaction itself by refining their own prompts, tone, and follow-up questions. In doing so, they became more aware of how meaning is constructed in dialogue, an experience that aligns with recent design-based work emphasizing critical AI awareness through active use and revision, as discussed by Hernandez, Medina, and Freynik (2024).

Taken together, these three classes highlight how the same AI chatbot platform can support learning in different, complementary ways. The patterns described here reflect our synthesis of classroom observations and student reflections across activities, rather than a focus on any single interaction. In the culinary history course taught in English, Mizou functioned as a tool for disciplinary inquiry, encouraging curiosity-driven questioning, historical imagination, and personalized exploration. In the Italian language and literature courses, it became a space for sustained language production, supporting extended writing, deeper engagement with texts, and low-stakes communicative risk-taking.

These parallel implementations demonstrate that Mizou is not limited to target-language practice alone but can also support disciplinary reasoning and creative inquiry beyond language learning, aligning with prior research on AI-supported language learning (Huang et al., 2022; Wiboolyasarin et al., 2025).

Our experience teaching with Mizou across these different contexts directly informed the conference session in which we presented this work to other teachers. Rather than presenting a single “best use” of AI, we invited participants to explore how the same tool could be adapted for content-based inquiry, target-language communication, or a blend of both, depending on instructional goals and context. The MIWLA session was intentionally designed not as a demonstration of best practices, but as a shared design space in which participants could experience AI-mediated tasks from the perspectives of learners, teachers, and designers.

Collaborative Teaching in Action at MIWLA

This dual use – content-driven inquiry and target-language communicative production – became the starting point for a professional development session we facilitated at the MIWLA (The Michigan World Language Association) conference. Instead of simply showing what our students had done, we invited teachers to experience Mizou firsthand, moving between the roles of learners, teachers, and designers.

Our session mirrored the progression of our classroom activities. We began with curiosity-driven exploration, asking participants to interact with a model chatbot drawn from one of Silvia’s courses. This allowed them to experience the activity as learners before shifting into hands-on practice designing chatbots for pedagogical purposes.

|

|

|

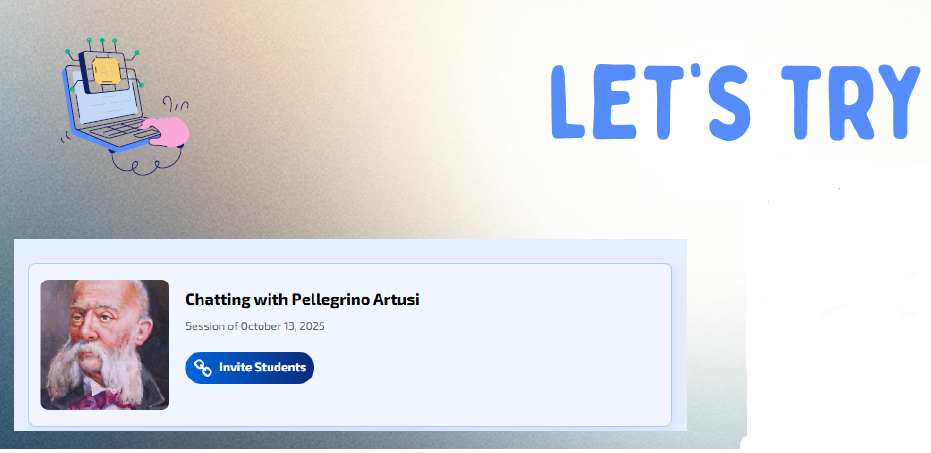

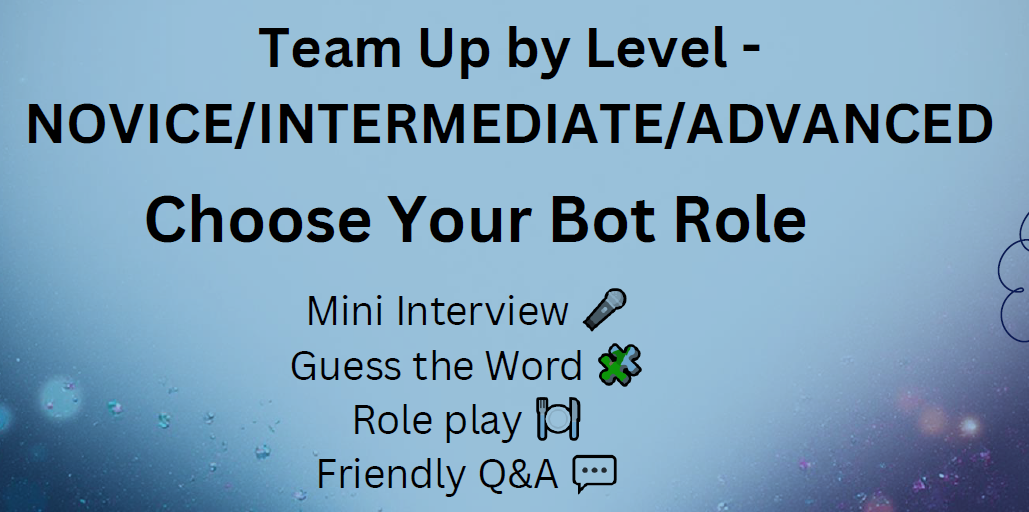

Participants interacted with a model bot, then followed structured steps to design their own in Mizou. From there, we moved on to structured bot creation aligned with proficiency levels. Knowing that time would be limited, we introduced “Bot Recipes” – light scaffolds designed to give groups an immediate entry point while leaving room for adaptation and creativity.

| Bot Recipe | Skill Focus | Mode of Interaction |

| Mini Interview | Introductions and follow-up questions | Novice interpersonal writing |

| Guess the Word | Contextual vocabulary and inference | Interpretive engagement |

| Role Play | Café orders, travel scenarios, mock interviews | Simulated real-world exchanges |

| Friendly Q&A | Low-stakes fluency and confidence building | Anxiety-reducing conversation |

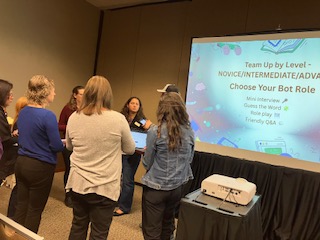

Within minutes, groups began to exchange ideas and debate with each other about which functions were appropriate for their instructional levels. They also experimented with how prompts and instructions shaped chatbot behavior. As illustrated in Picture 5, participants quickly shifted from passive observation to active chatbot design. They gathered around laptops, tested ideas in real time, and negotiated design choices together. Although time ran out before groups could fully share or reflect on the bots they were building, the energy in the room was palpable. We had created a Padlet for sharing the bots, and one group managed to complete and upload theirs before the session ended, a small but joyful victory for real-time creation. In that moment, the session became a kind of laboratory, in which teachers experimented, asked questions, and collaboratively shaped a pedagogical AI tool, rather than simply learning about it.

|

|

|

What We Learned from Watching Teachers Learn

Just as in our classrooms, curiosity proved contagious. As facilitators, we watched participants move quickly from tentative exploration to purposeful design discussing prompts, anticipating student responses, and refining ideas in response to what the chatbot produced. Even without a formal debrief, it was clear that engaging with the tool as both learners and designers shifted how educators thought about AI: not as something to adopt unconditionally, but as something to question, shape, and adapt with intention. Across all contexts – culinary history, Italian language and literature, and teacher professional development – the common denominator was agency: the freedom to ask questions, guide interaction, and see language respond back.

Pedagogical Takeaways

Here are some of our best takeaways for those who would like to try out these kinds of activities in their own classrooms.

Start small. Begin with a simple activity, such as a vocabulary game or a short conversational warm-up.

Define a purpose. Make sure the chatbot supports a clear learning goal: intercultural awareness, grammar in context, or guided reflection.

Encourage agency. Invite students to suggest prompts or redesign existing ones.

Keep it safe. Choose tools that protect privacy and do not require personal login (the free version of Mizou worked well for this).

Stay human. AI can support learning, but the empathy, humor, and care we bring to the classroom remain irreplaceable.

Throughout this work, our goal has been to show how AI can remain firmly in the service of thoughtful teaching rather than driving it.

Looking Ahead

Our work with Mizou has shown us something simple but powerful: when teachers begin with a clear pedagogical intention, building and using a chatbot is not only doable – it’s energizing. At MIWLA, we watched educators move quickly from curiosity to design, adjusting prompts, tone, and audience much as they would refine classroom instructions. The technology became transparent, shapeable, and teachable.

If you’re curious about trying Mizou specifically, you can explore the platform at https://mizou.com, where educators can build chatbots without requiring student accounts and experiment with both free and paid features. Beyond Mizou, we are also interested in continuing to explore how other educator-facing AI tools – particularly those that allow for customization, multilingual interaction, and embedded course materials – might support similar goals across disciplines.

AI is not here to take over teaching. It offers new ways to provoke thinking, lower affective barriers (Krashen, 1982), and stretch language beyond the page. What matters most is not the tool itself, but the intention behind it. One thoughtfully designed task, one conversation, and yes – one bot at a time.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Dr. Cori Peet of Wayne State University for her generous advice and continued support.

AI disclosure

Minimal use of AI: Generative artificial intelligence was used in the preparation of this article only for brainstorming ideas or for spelling and grammar suggestions.

References

Dale, J. (2025, September 19). AI in the languages classroom: Enhancing, not replacing the teacher’s role. National Consortium for Languages Education.

https://ncle.ucl.ac.uk/blog-ai-in-the-languages-classroom-enhancing-not-replacing-the-teachers-role/

Deckker, D., & Sumanasekara, S. (2025). The role of artificial intelligence in education: Transforming learning and teaching. EPRA International Journal of Research and Development.

https://doi.org/10.36713/epra20429

Hernandez, M., Medina, R., & Freynik, S. (2024, October 22). Designing & building AI chatbots in the language classroom [Workshop presentation]. Amplify Professional Learning Experiences, Center for Language & Technology, University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa.

https://go.hawaii.edu/ap9

Huang, W., Hew, K. F., & Fryer, L. K. (2022). Chatbots for language learning—Are they really useful? Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 38(1), 237–257.

https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12610

Krashen, S. D. (1982). Principles and practice in second language acquisition. Pergamon Press.

Mizou. (n.d.). Mizou educational platform. https://mizou.com

Spirydovich, N. (2025). Making space for real conversations: AI chatbots in the language classroom. The FLTMAG.

https://doi.org/10.69732/YHRJ4554

Wiboolyasarin, W., Wiboolyasarin, K., Tiranant, P., Jinowat, N., & Boonyakitnon, P. (2025). AI-driven chatbots in second language education: A systematic review of their efficacy and pedagogical implications. Ampersand, 14, 100224.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amper.2025.100224