5 Takeaways from “Design For How People Learn” by Julie Dirksen

By Shannon Donnally Quinn, Michigan State University

DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.69732/PCRZ3279

This short article is part of a new series called “5 Takeaways”, in which the author of the article gives their reaction to a book or other type of media with what the author deems to be the 5 most interesting or most useful points from the source that can relate to language learning, whether big or small.

Introduction

This book, published in 2012, offers a clear and accessible introduction to key principles of instructional design. In selecting my five takeaways, I assume that most readers of The FLTMAG already have an implicit or explicit understanding of many of the book’s central ideas. For that reason, I focus here on several less obvious points that may be particularly thought-provoking. Overall, the book is well worth reading: for those new to instructional design, it provides a solid overview, and for more experienced readers, it serves as a useful reinforcement of core principles. The book is also rich in concrete and engaging examples drawn from a wide range of fields, though only a small number come directly from language learning.

Takeaway 1: Consistency is helpful for cognitive load, but has to be balanced against habituation.

When lessons follow a consistent design, learners can focus their cognitive resources on the content rather than on figuring out the format or interface, which supports more efficient learning. At the same time, too much consistency can lead to habituation, which is when something becomes so familiar that it fades into the background. For instance, if feedback always takes the same form (“Great job!”), learners may stop noticing it altogether. Varying feedback can help recapture learners’ attention, especially when that feedback provides specific, meaningful information that supports learning. Variety can be achieved simply by providing specific feedback for specific errors, but there are many other ways to encourage learners to notice and engage with feedback. For example, mixing written and audio feedback can be effective, depending on the task and context. Visual feedback – such as stickers, icons, or emojis – can also be motivating and help draw learners’ attention to key points.

Takeaway 2: It’s important to present learning objectives to learners, but there are many better ways to do it than with bullet points on a slide.

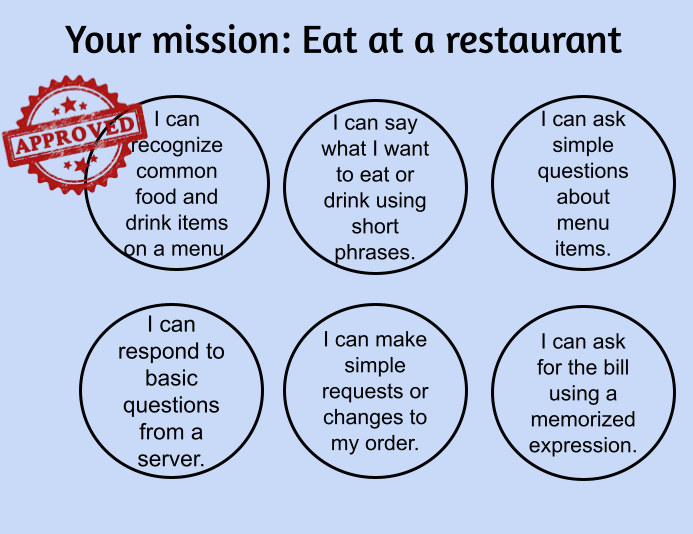

Due to habituation, learners will often disregard bullet point lists of learning objectives. Dirksen suggests using more exciting ways of presenting objectives to learners: “…use a challenge, a scenario, or a ’your mission, should you choose to accept’ message.” She also suggests using unexpected language that focuses more on what people will actually do with what they learn. Compare these two sets of learning objectives. Which set of lessons sounds more interesting and catches your attention?

Photoshop for Beginners – Lesson Outline

| Lesson 1: Working with layers | Lesson 1: How to create a swanky blog header |

| Lesson 2: Photo-editing tools | Lesson 2: How to make a so-so photo look amazing |

| Lesson 3: Working with filters and effects | Lesson 3: How to create an album cover |

| Lesson 4: Using the Pen tool | Lesson 4: How to remove your ex from your sister’s wedding pictures |

ACTFL Can-Do statements also attempt to turn the focus to what students will be able to do with the language that they are learning, but learners can become habituated to them also if they are presented the same way every time. Some ideas for creative presentation of learning objectives could include:

- embedding the objective in a scenario or narrative

- presenting students with a “mission card”

- giving students stickers or stamps when they achieve objectives

- having students participate in figuring out what the objectives will be based on examples or an image

Takeaway 3: Feedback that shows what happens as a result of learner choice is better than explicit feedback (Correct/Incorrect) – this first kind of feedback creates friction.

As Dirksen explains, one of the important elements for learning is friction, “something that requires learners to chew on the material, cognitively speaking”. Dirksen says it this way: “…telling is smooth, but showing has friction: it requires learners to make some of their own connections to interpret what’s going on.”

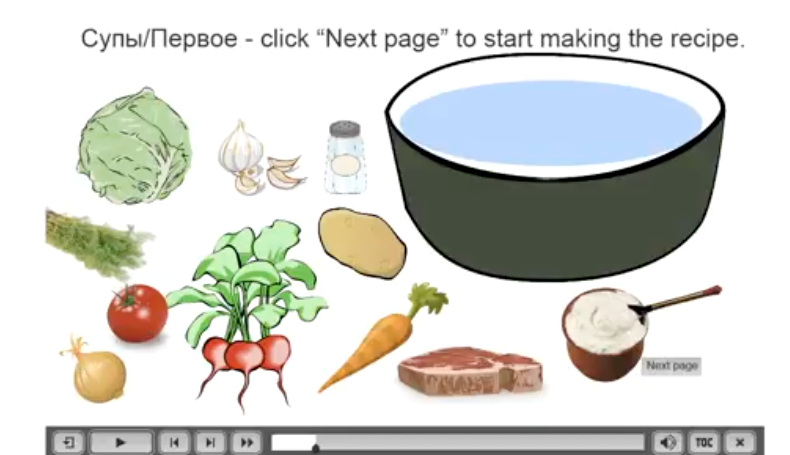

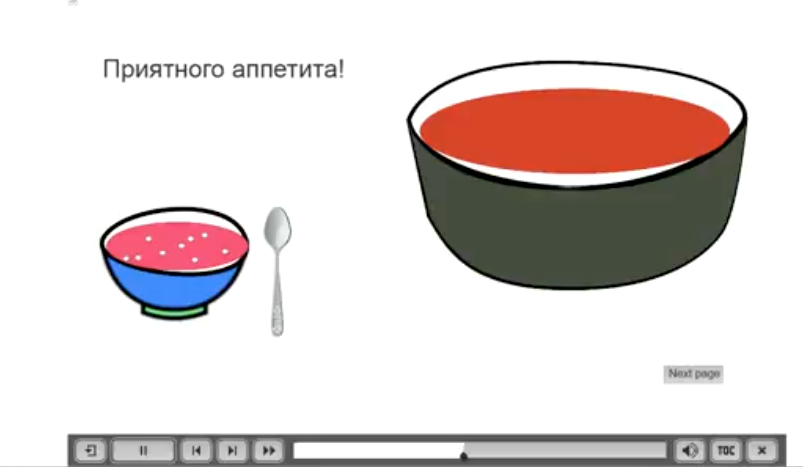

While it’s not always easy to do this, we should try to do it when we can. In reading the description I was reminded of a task in an old activity of mine that I was particularly proud of. I had made a set of lessons that were intended to help students prepare for study abroad. In one of the lessons, the learners were asked to make a virtual bowl of borshch (soup). They had to listen for the ingredients and then drag them to the bowl. When the soup was finished, the bowl turned red (as borshch does in real life) and the learner was given a virtual bowl of soup. Now that I think about it, part of the reason why I liked this activity so much was that the feedback mimicked the natural positive consequences of correctly making a recipe.

|

|

|

Takeaway 4: Proximity is important – put the knowledge necessary near to the task.

This principle applies in many instructional contexts. One clear example is information gap activities: learners are more successful when the information they need is easy to access and located close to the task itself, rather than buried elsewhere or requiring unnecessary searching.

The importance of proximity also extends to the overall organization of a course. This idea has been especially salient to me recently as I have been learning a new language myself – Kazakh. Because Kazakh is a less commonly taught language, learning materials for English speakers are relatively limited, and my instructor has drawn from a wide range of sources. While this approach is not problematic in itself, I eventually created a challenge for myself by failing to develop a clear system for organizing those materials. When I wanted to review or revisit something, I often struggled to locate the relevant resource.

I have since developed a much more effective organizational system, but this experience has reinforced an important lesson: whenever possible, we should do this organizational work for our students by placing the resources they need in close proximity to the tasks they are completing. At the same time, we should not assume that students already know how to organize their learning materials effectively. Explicitly coaching them in developing their own organizational systems can be a part of supporting successful learning.

In digital contexts such as course management systems, “proximity” often refers to how many clicks learners must make to engage with a particular activity. To improve proximity, instructors can revise their online curricula so that the supports learners may need, such as instructions, grammar charts, dictionaries, or information for an information gap activity, are embedded directly on the same page as the task itself. Reducing this digital distance allows learners to focus more fully on learning rather than on navigating the interface.

Takeaway 5: Creating emotional contexts is an important, but often overlooked element of learning design.

Of course, the classroom is inherently different from the target culture, and there is nothing that can completely prepare learners for the moment when they step off the plane and have to start using the target language “for real”. And we do want to provide a safe place for students to practice and take risks. But creating some of the pressure that students may feel when using the target language in the target culture will also help them to practice functioning under that pressure. Dirksen believes that the failure to replicate the true emotional context is the reason that a lot of learning fails: “Have you ever said to yourself ‘I knew the right thing to do, but…’ The difference between knowing and doing can be a huge gap when the context of encoding and the context of retrieval are significantly different.”

To address this gap, Dirksen suggests incorporating role-playing and deliberately introducing pressure into learning activities, even if that pressure differs from what learners will face outside the classroom. Time pressure, in particular, is highlighted as a practical way to approximate real-world emotional conditions. Role plays of high stakes situations like job interviews, medical visits, or border crossings, while they can probably never completely recreate the stress of those situations, can at least give students an approximation of and an awareness of what it might be like to undergo those real life interactions.

The emotional context helps explain why language exchanges and telecollaboration can be such powerful tools. While interactions with classmates or tutors may replicate many aspects of the linguistic context, telecollaboration is uniquely positioned to mirror the emotional stakes of communicating with real interlocutors from the target culture – where misunderstandings feel more consequential and success feels more meaningful.

Conclusion

If you are a teacher that designs your own curriculum but doesn’t have a lot of background in instructional design, this book would be a really useful introduction. There is also now a newer edition that has three new chapters: Design for Habits, Social and Informal Learning, and Designing Evaluation.

Dirksen’s book highlights the way in which instructional design is a balancing act, and often a natural tension between extremes. Consistency in design can help students to learn, but too much consistency might make them stop paying attention. Making learning easy is desirable, but making it too easy would eliminate the friction and emotional context needed for deep learning. As teachers and instructional designers, we continue to seek this balance.

References

Dirksen, J. (2012). Design for how people learn. Berkeley, California: New Riders.

AI disclosure: Minimal use of AI: Generative artificial intelligence was used in the preparation of this article only for brainstorming ideas or for spelling and grammar suggestions.

I noticed the author used a mission card example, which is pretty cool. The idea of giving students stamps for achieving objectives makes me think about how I could apply this in my own teaching.

This is an insightful summary of Dirksen’s work! I believe integrating game mechanics into learning design, as discussed here, could enhance engagement significantly.

Thanks for sharing this post about the takeaways from Julie Dirksen’s book. I love the ‘5 Takeaways’ series idea—it’s a great way to digest key points quickly. Looking forward to more in this series!

Great article! The five key takeaways on Design for How People Learn are really practical and insightful. It’s helpful to see learning principles clearly tied to real design strategies that can improve engagement and retention.