Language, Culture, and Community: Fostering Learning through an Interinstitutional Online Game

By Molly Godwin-Jones, Dianna Murphy, and Karen Evans-Romaine

Introduction

The widespread shift to remote instruction and adoption of video conferencing tools such as Zoom during the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in new opportunities for educators at various institutions to collaborate on shared co-curricular programming for students. This article describes one such opportunity: Kino and Russian Rock, a multi-institutional, co-curricular learning experience in spring 2021 for students in Russian Flagship programs. The project was envisioned by the Language Flagship Technology Innovation Center (Tech Center) as a co-design initiative to fulfill its goal of fostering a culture of innovation through partnerships and processes that enhance the Language Flagship experience (Rodriguez, 2018). The project included faculty and directors from the eight U.S. colleges and universities that currently offer Language Flagship programs for Russian language (Bryn Mawr College; Indiana University; Portland State University; University of California, Los Angeles; University of Georgia; University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; University of Wisconsin-Madison; and Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University) and was co-facilitated by the co-directors of the University of Wisconsin-Madison Russian Flagship program, with instructional, technical, and logistical support from the Tech Center faculty and staff. The co-design aspect of the project was important so that all stakeholders were involved in the planning process, creating a more equitable experience for all. In all, around 20 people participated in planning the event.

The Language Flagship is a national initiative funded by the Defense Language and National Security Education Office, which prepares undergraduate students in any major to reach a professional level of competence (ACTFL Superior/ILR 3) in their language of study by graduation (Murphy & Evans-Romaine, 2017). There are currently 31 Language Flagship Programs funded through this initiative in languages designated as critical to U.S. national security and economic competitiveness, including Russian.

As part of this project, Tech Center faculty at the University of Hawai’i at Mānoa worked closely with faculty from all eight Russian Flagship programs to conceptualize, plan, and carry out a shared program of activities that incentivized collaboration across all programs. The project culminated in an online game, based on a contemporary Russian film, which engaged teams of students with diverse levels of proficiency in Russian from the eight participating institutions. The goal of the co-designed experience was twofold: a) to improve the learners’ knowledge of culture by providing them with an opportunity to learn about a contemporary historical period through the fictionalized characters depicted in the film; and b) to foster a broader sense of community among Russian Flagship students and faculty across institutions.

Project Planning

The project began in fall 2020 with brainstorming meetings to determine the type of experience to be co-designed. In previous years, faculty at Russian Flagship programs and the Tech Center had focused on professional language and worked together in the simulation of a professional online conference for advanced Russian Flagship students. In 2020-2021, the planning committee (consisting of one representative from each institution, plus two co-chairs and a Tech Center representative), decided instead to co-design activities that would be open to students at any level of Russian, that would promote community-building among Russian Flagship students, and that would be a fun experience for students coping with the many stresses related to the global pandemic. Rather than a professional conference, the planning committee settled on an online game. Following lengthy discussions about different types of games, and a survey of students regarding their preferences, the planning committee chose to host a game modeled on the popular Russian TV game show Что? Где? Когда? (What? Where? When?). This show involves members of a team working together to answer trivia questions and earn points.

An initial challenge, however, was that participating students would not come to the game with a shared basis of cultural knowledge or at the same level of proficiency in Russian. In order to address this issue, the planning committee made a significant modification to the structure of the original Что? Где? Когда? (What? Where? When?) game, basing the trivia questions around a shared set of learning experiences. These shared experiences included viewing a Russian-language film, subtitled in English, that students would watch before the game; attending an invited lecture in Russian on the topic of the film open to all participating students; and completing a series of online learning activities. The learning activities, all intended to prepare students for the game, were based on the film, online materials about the cultural context of the film, and the lecture. The planning committee developed the following criteria for selecting the film: it needed to have cultural or historical relevance, appeal to students already facing a variety of challenges during the pandemic (films with major themes of loss or grief, for example, were excluded), and be available to stream online with English subtitles. After reviewing several films that might meet these criteria, the 2018 film Лето (Summer) directed by Kirill Serebrennikov was selected for its historical and cultural richness, its aesthetic qualities, and its topic. The film provides a rich portrayal of the legendary rock musician Viktor Tsoy and his band Kino, of the underground rock scene in Leningrad in the 1980s, and of the relationship between the state and society in the late Soviet period.

Once the film was selected, the next step was to ensure student access at all eight institutions. All institutions subscribe to the film service Kanopy, and most used this platform to provide streaming access to the film. Each institution organized “local” online viewing sessions for their students, with some turning the opportunity into a club-style event, such as a viewing party on Zoom using the “share screen” function, followed by a discussion. Some institutions implemented a slightly different approach to a viewing party, with students logging on to Zoom for an introduction to the film, then turning their cameras off and muting themselves to watch the film on their individual screens. Viewers could send messages and make comments using the chat function. Once the film was over, they turned microphones and cameras back on and had a discussion. Other institutions assigned the film as homework for students to watch on their own. Students were also given instructions on how to view the film on their own through their institutional streaming services if they were unable to attend a viewing party or wanted to watch it again on their own.

To enrich students’ understanding of the people and events depicted in the film, the University of Wisconsin-Madison Russian Flagship, with funding from the Center for Russia, East Europe, and Central Asia, sponsored an invited lecture by well-known Russian journalist and rock expert Artemy Troitsky. His online talk, Viktor Tsoy and Kino: Myths and Reality of Russian Protest Rock Music, provided a historical and personal background to the Russian rock scene of the 1980s based on Troitsky’s own experience working with Tsoy and Kino. The talk was conducted in Russian and recorded so that participating students could rewatch it as they prepared for the game later. Several faculty members took extensive notes on the lecture and time-stamped the notes. If the timing of future iterations allowed for subtitling or selective captioning, that would increase the accessibility of the lecture to students at lower levels of proficiency. The UW-Madison Russian Flagship also created a number of Spotify playlists of music from the film, and of songs by Kino and other Russian rock groups to which students were encouraged to listen.

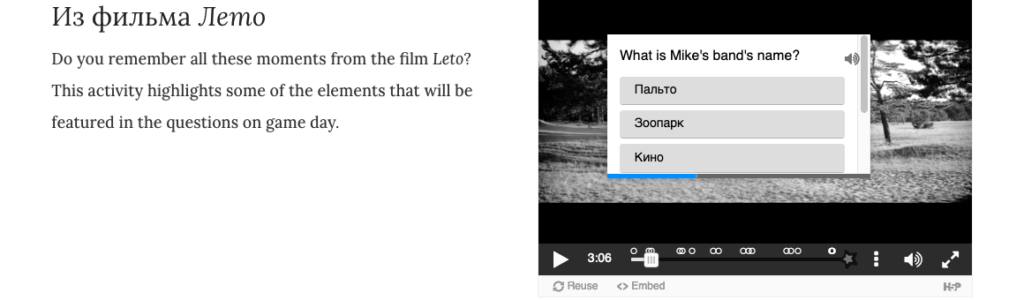

To help students prepare for the game, faculty on the planning committee provided a series of four online learning activities, which consisted of already existing activities, adaptations of existing materials, and entirely new activities. The first activity was an existing H5P task based on film director Kirill Serebrennikov’s advice on living in isolation, created by Shannon Donnally Quinn (Michigan State University) and available through LLC Commons (hosted by the Center for Educational Resources in Cultural, Language, and Literacy). In addition, planning committee members developed three additional sets of learning activities based on the film, on the lecture by Artemy Troitsky, and on other materials, such as YouTube clips (news reports and biographical videos on Tsoy) and a resource on Communal Living in Russia: A Virtual Museum of Everyday Life, developed by faculty at Cornell and Colgate Universities and hosted at Cornell. The activities were created with H5P and included interactive exercises such as true/false statements, multiple choice items, and fill-in-the-blank questions (see Picture 1).

The H5P activities focused primarily on the cultural context of the film and its subject. Quizlet was used to help students learn new vocabulary and to create a flashcard set. Since the game was open to students at any proficiency level in Russian, the flashcards included some vocabulary that might have been familiar to advanced students but new to beginners.

To help students keep track of all these resources, the Tech Center hosted a website with links to all the needed materials. This site served as a hub for activity related to the game, and was updated as new resources became available.

Given the many and varied tasks to prepare for the game, the planning committee formed three subcommittees: one to develop the H5P learning activities, one to create the trivia questions for the game, and one to design and plan for the game itself. An especially complex and time-consuming task for the game planning subcommittee was dividing students into teams. A mix of students from different institutions and proficiency levels in Russian were placed on each team to provide opportunities for students across institutions and levels of instruction to meet and interact with one another. Initially, 56 students signed up to participate in the game and were placed into ten small teams of 5-6 to encourage intergroup communication. A workspace on Slack was created to help students communicate with each other. This workspace included public channels with information relevant to all participants, such as the “welcome” channel where links to the pre-game activities and Quizlet set were posted, as well as private channels: one for each team, one for the organizers, and one for the game judges.

One of the most challenging aspects of coordinating the game was readjusting the student teams based on attrition. Over the course of the pregame period, almost half of the students who signed up dropped out of the game, with a final total of 29 students on game day. One suggestion from planning committee members to address this high level of student attrition in future iterations of the game is to shorten the time between registration and the event. In this first iteration of the game, there were six weeks between the registration deadline and the game itself. In the future, we are planning for a shorter time frame – two or three weeks – between the initial sign-up and the event itself. Integration of activities into courses, or at least providing students extra credit in their Russian courses for participation in this activity, would also help maintain student motivation.

The subcommittee focused on designing pre-game activities coordinated closely with the subcommittee writing the game’s trivia questions, in order to ensure that questions in the game addressed material that students had seen before in the pre-game online activities, and to ensure that both the pre-game activities and the questions allowed for participation by students with varying levels of proficiency in Russian. Subcommittee members divided tasks and developed the pre-game activities in pairs or small groups. Committee members found and time-stamped relevant video clips on Tsoy’s biography from YouTube and created activities and questions based on them, on the Troitsky lecture, and on the Cornell University site on communal apartments. Subcommittees coordinated their work through Google docs, so that each activity developed logically from the one previously assigned. As all committee members had access to all of the planning documents from each subcommittee, coordination of activities was seamless.

The subcommittee focused on drafting the trivia questions initially worked independently to create questions and answers in a Google document that could potentially be used in the game. In total, 71 questions were drafted, which far exceeded the number required for the game. To help organize the questions, the subcommittee decided to structure the game in four timed rounds. Each round was based on questions related to a central theme: Round 1 covered Tsoy’s biography; Round 2 focused on facts about the film; Round 3 focused on characters and places in the film; and Round 4 contained more challenging questions on the cultural context of Tsoy and Kino. (Ultimately, on game day, moderators had to cut the fourth round due to time constraints.) In case the score was close or tied among the teams, the question design subcommittee planned for a final “Captain’s Round,” in which only the team captains participated. The first rounds consisted primarily of multiple-choice questions, with one or two short-answer questions; the Captain’s Round, on the other hand, was much more difficult: all questions were open-ended. In the initial rounds, each question was worth one point. In the Captain’s Round, point values varied. Tech Center staff used the Wheel of Names website to create an online spinning wheel that allowed game moderators to vary the point value of each question in the Captain’s Round from one to three points, depending on where the wheel fell. The Captain’s Round also used an online buzzer system, also found by Tech Center staff, for each team captain to buzz in, with the first person to buzz in getting the chance to answer the question first. (Team captains logged into Zoom early on game day to test the buzzer system with the game host.) Once the questions were divided into rounds, they were edited by Russian native speakers on the planning committee and reviewed by the question design subcommittee before being added into the slide deck (see below).

The subcommittee focused on planning for the game devoted significant time to aligning the design with the format of the Russian game show Что? Где? Когда? (What? Where? When?), adjusting to the online format with teams of physically dispersed participants. The committee chose to use the videoconferencing tool Zoom as the platform to host the game, given that faculty and students were by that point of the pandemic familiar with Zoom, and the ease of creating private spaces – breakout rooms – that could be used by teams of student contestants to confer and to submit their answers to trivia questions. Planning for the game also included specifying the many different types of roles that participants – including the faculty and instructional technologists – would play. The main roles included the game host, three judges to score student responses, three question-readers (who were responsible for reading the questions out loud during the game), a DJ, two game-day directors, a technical support team, and alternates for as many roles as possible. Volunteers for these roles were from the planning committee, faculty and staff from the Russian Flagship programs, and the Tech Center.

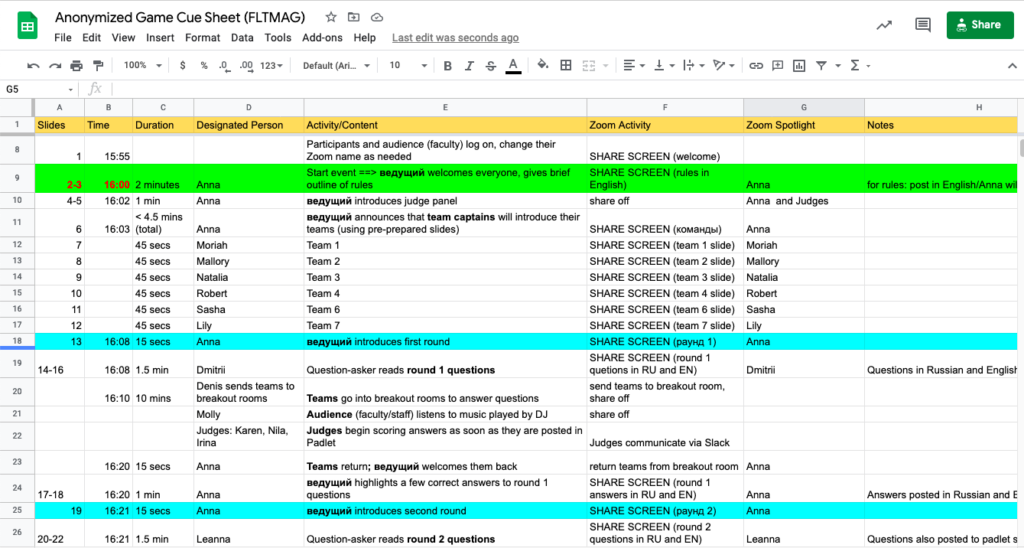

In addition to the work by the subcommittees, planning also included specifying, minute-by-minute, the interactions of the game through a cue sheet created using Google Sheets. This spreadsheet included the specific time for each activity, the duration of the activity, the person responsible for carrying out the task, and technical notes (e.g., regarding screen sharing), whether the spotlight feature in Zoom was needed, and a place for notes about the activity. The cue sheet was color-coded for quick and easy reference on game day (see Picture 2).

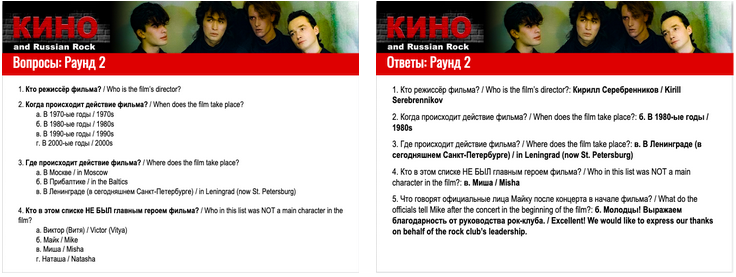

In addition to the cue sheet, intended for internal use, a slide deck using Google Slides was developed to organize all the questions for game day. The questions were initially drafted using a basic Google document, and then the final version of the questions, in both Russian and English, was added to the slide deck along with the correct responses so that students could review after submitting a response (see Picture 3).

As the name of the final round suggests, each team elected a captain who was responsible for additional tasks. In addition to representing the team in the Captain’s Round, the captain was the driving force behind the team’s preparation for the game. Preparation included finding a time to meet to determine a team name and to complete a team intro slide. On game day, the captain had additional responsibilities as well, such as introducing the team to the audience, helping to coordinate team discussion in breakout sessions, and ensuring that team answers were posted for the judges.

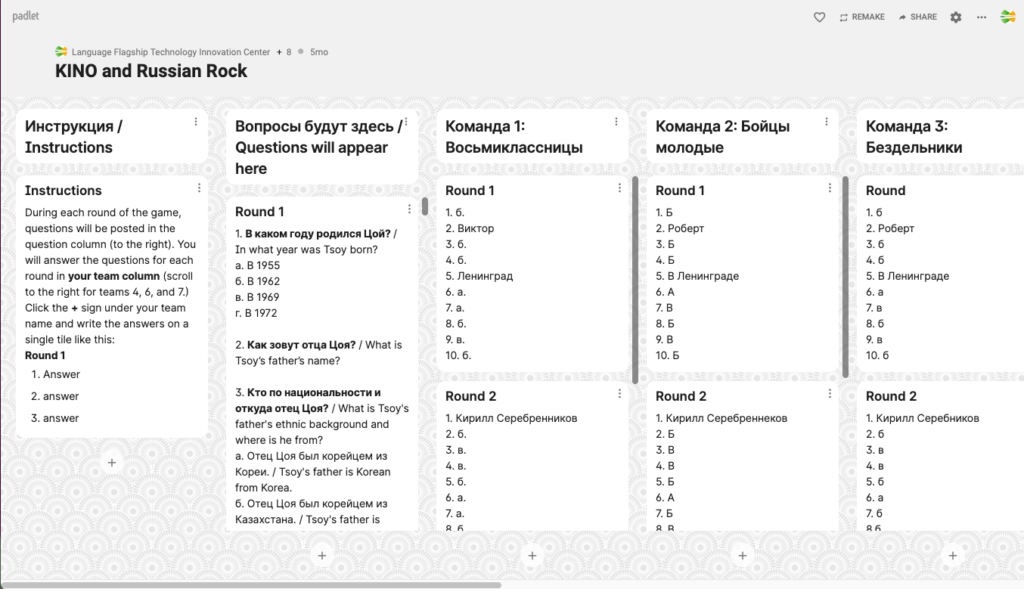

A final preparatory logistical task before game day was to develop a system for the teams of student contestants to submit answers to the panel of judges without the other teams seeing those answers. The Tech Center proposed using Padlet to create a page for each team to post their answers while in separate Zoom rooms, with the teams returning to the main room after each round to find out the score. To ensure that teams couldn’t view others’ answers until they were submitted to the judges to be scored, the Padlet page was set to “Require Approval” for posts. A Tech Center representative monitored the Padlet page, and, once each round was completed, approved the team’s posts to become public for the judges to review. Some teams completed the questions much more quickly than others, however, so the judges were, in fact, granted login access to the Padlet page in order to be able to begin scoring team answers before the round was completed (and therefore before the answers were publicly posted), once the team indicated they were finished. In addition, the Tech Center posted the questions on the Padlet page for students to reference as they were answering the questions (see Picture 4). A private Slack channel was available for the judges to confer on any questions as they worked.

Game Day

The game lasted 75 minutes, not including a short pre-game preparation sound-check and orientation meeting with team captains and event organizers that lasted approximately 30 minutes. As noted above, a total of 29 students participated from all eight participating Russian Flagship programs. Students were at various proficiency levels in Russian, with the largest group of students enrolled in third-year Russian courses. In addition to students, 17 faculty and staff from the participating institutions attended the event, the majority of whom fulfilled a role in running the game, leaving seven audience members who were simply spectators. In addition to the students and Flagship faculty and staff, seven Tech Center representatives also participated in the game, mainly to provide technical support, such as monitoring the Padlet page and running the slide deck.

The decision as to whether to invite an audience of instructors, students, and staff was difficult and involved fairly extensive discussion. Ultimately, planning committee co-chairs decided not to invite an audience, given the complexity of the game and the lack of time to develop a plan for entertaining the audience while the teams of student contestants were deliberating and submitting answers in Zoom breakout rooms. Future iterations of the game could include an audience if there were activities or performances to keep them engaged while the student teams collaborate in the Zoom break-outs. One option discussed by the planning committee, but ultimately abandoned due to time constraints, was having students who were not participating in the game perform during the breakout room sessions, or showing videos of student performances.

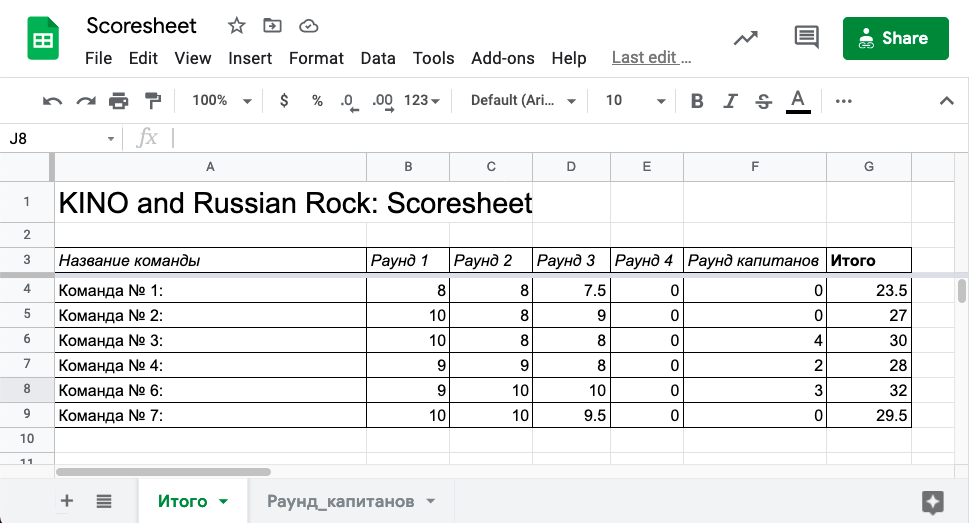

The event flowed smoothly thanks to the detailed information on the slide deck, the cue sheet, and a dress rehearsal (without student participants) a few days before game day. The spoken language of the game was entirely Russian; there was some English on the slides, as each question was displayed in both Russian and English. The game began with an introduction by the host, who reviewed the rules (which were displayed in English in the slide deck) in Russian. After the rules were explained, each team captain briefly introduced their team in Russian using the team slides they had submitted prior to game day. Next it was time for the game to begin! For each round, the questions were read out loud in Russian by a volunteer; they were also displayed (in Russian and English) on the slide deck. All rounds had ten questions. After all questions (and their answer options) in a round were read aloud, the teams were sent to breakout rooms for 5-7 minutes to discuss their answers and post their responses to Padlet. Once each round was completed, students returned to the main room. Judges scored the responses as participants moved on to the next round. Judges recorded scores for each team in a Google Sheets spreadsheet that automatically calculated the totals for each team (see Picture 5). After Rounds 2 and 3, the host announced the running scores.

The final Captain’s Round was lightning-style, with the team captains competing to buzz in first to answer the questions. Teams were encouraged to help their team captain by backchanneling through their private Slack channel or through some other pre-arranged system of communication. As noted above, the questions in the Captain’s Round were worth one to three points, with point values determined by the Wheel of Names spinner; this allowed some teams that were behind to make up lost points.

Ultimately, the final scores were very close, with the winning team earning 32 points, the second place team 30, and the third place team 29.5. (The judges awarded half points for some questions in rounds 1-3 that were not multiple choice.) As a prize, members of the winning team received credit to the website FilmDoo to watch a Russian film of their choice. Before the game ended, a link to an evaluation questionnaire was posted in the chat; the link was also later emailed to students, so that they could provide feedback on their overall experience with the game, and with the pre-game activities.

Reflection

Overall, students found the game, and the series of activities leading up to it, to be a positive experience. They reported a desire to have more time to interact with their teammates in synchronous sessions, which suggests that future iterations of the game should include longer breakout room times, or more get-togethers before the game for teams to meet and get to know each other.

The project event was an overall success and fulfilled the goals of facilitating both language and culture learning and communication and community-building among students in the eight Russian Flagship programs. Faculty involved with the project reported positive reactions to its implementation and were excited about potential future iterations of the project. In the future a full year would be ideal, given the scope of the project – to envision and design the game, select and obtain rights to screen the film, develop the pre-game activities, and host the pre-game screenings and lecture. We would also request that participating students sign an optional media release waiver before the game so that we could share screenshots and recordings. As previously mentioned, in future iterations, to decrease attrition, we would also plan for a shorter time span between participant registration and the game itself. Finally, we would include more pre-event meetups for teams of students to have the chance to get to know each other better before the game.

Implementing a multi-institutional trivia game as a co-curricular learning experience was no simple task. It was, however, incredibly rewarding. It is a complicated endeavor, but possible for non-Flagship institutions to implement. It would require faculty and staff at each participating institution to invest the time in online planning meetings, selecting a film together, gaining rights for each institution to show that film, and developing online learning activities together. The support of each institution’s instructional technology staff would be critical. It would be ideal for the materials for such a game to be integrated into language classes at the appropriate level, which would mean an extra semester’s planning in order to make such integration possible. Thus an ideal start time would be spring semester one year prior to the game, giving planners the spring, summer, and following academic year to plan, select a film, obtain rights to screen the film, develop learning activities, allow for student registration, create teams, bring the student teams together in advance of the game, and hold the game. Although a game show requires great investments of time and cooperation between institutions, it is a great way to introduce a cultural topic that may not have received instructional attention in the curriculum, and providing scaffolding such as pre-event learning activities and translations of game question slides can help make the event accessible to students at all proficiency levels. Even after the pandemic ends, we hope to continue collaborating with colleagues at other colleges and universities to offer shared co-curricular programming that brings students together for shared learning in a fun, low-pressure, and culturally rich environment.

Acknowledgments

The Kino and Russian Rock project was funded through The Language Flagship Technology Innovation Center (Tech Center) at the University of Hawai’i at Mānoa under a grant from the Institute of International Education (IIE), acting as the administrative agent of the Defense Language and National Security Education Office (DLNSEO) for The Language Flagship. One should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government. The first author of this article, Molly Godwin-Jones, was the Tech Center lead for this project. The second and third authors, Dianna Murphy and Karen Evans-Romaine, co-directors of the University of Wisconsin-Madison Russian Flagship Program, were project co-leads and co-chairs of the planning committee.

Members of the planning committee, all affiliated with Russian Flagship programs at their home institutions, were Irina Walsh, Bryn Mawr College; Sofiya Asher, Indiana University; Nila Friedberg, Portland State University; Olga Thomason, University of Georgia; Meredith Doubleday, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; Susan Kresin, University of California, Los Angeles; Kirsten Rutsala, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University; and Anna Tumarkin, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Instructional designers from the Tech Center included Julio Rodriguez, Suzanne Freynik, Naiyi Fincham, Stephen Tschudi, Denis Melik Tangiyev, and Dmitrii Egorov.

Spotify playlists were created by Iuliia Nogina, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

References

Murphy, D., & Evans-Romaine, K. (Eds.). (2017). Exploring the U.S. Language Flagship Program: Professional competence in a second language by graduation. Multilingual Matters.

Rodríguez, J. C. (2018). Redesigning technology integration into world language education. Foreign Language Annals. 51:233–239. https://doi.org/10.1111/flan.12328

Groundbreaking project that opens the door to more learning activities in more languages that engage students and enhance their motivation to pursue longer sequences of study and, therefore, greater learning outcomes. Bravo to all those who worked on this project!

Outstanding article about a truly amazing project!! Thank you very much for the detailed explanation and for sharing your experiences with us! I’m very interested in hearing how future iterations play out and I’d love to give this a try in an EFL context among universities in Japan.

Поздравляю Bac и с наступающим Новым годом!