Among Us: Bringing Fun Back to the Digital Language Classroom

By Erin Frazier, Kanda University of International Studies

Introduction

The digital shift to online teaching has sometimes meant leaving some of our more interactive and engaging activities to the wayside as we adjust to the new format. This is especially true when teaching second language learners, where instructors tend to lean heavily on tactile learning, communicative team building, and gamified activities to enhance the learners deeper understanding of the language; these methods are difficult to replicate online. My face-to-face classes would often begin or end with a game that reinforced what the students had been studying from vocabulary races to debate badminton. As Wright et. al. (2006) highlights “language learning is hard work … Effort is required at every moment and must be maintained over a long period of time. Games help and encourage many learners to sustain their interest and work” (p2). So the challenge has been to bring back games that appropriately aid in solidifying the acquisition of the target language while also considering the limitations of online teaching. I think the answer lies in how innovative instructors are with technology and adapting games that students already play during their free time, which could increase their motivation. There has been a boom in multiplayer online gaming this year that are more communicative in nature, from “Phasmophobia”, where you and your friends are using clues to figure out what kind of ghost is haunting different places, to “Heave Ho”, a game in which your team is trying to get across different obstacles by cooperating. “Among Us” is a guess who game, and the one that I chose to use for this communicative activity.

This is not the first time a guessing game has been introduced to the classroom. Face-to-face games like “Mafia” or the card game “One Night Ultimate Werewolf” have been used to improve communication skills through problem solving and analyzing empathy (Farber, 2016). Even the game “Keep Talking and Nobody Explodes”, which is a game where one player is in a digital environment with a bomb while the other player (not in the digital environment) has a manual to defuse the bomb, have been used as an information gap task (Domer et. al., 2017). Activities like these have put value on technology-mediated task-based approaches by mixing the usage of technology to aid in the language classroom (Thomas & Reinders, 2010). However, these tasks have usually incorporated some element of face-to-face interaction that led to the successful implementation of these activities. Many of us, however, do not have the option for hybrid lessons at this point due to COVID-19, and are conducting classes strictly online.

“Among Us”: The Game

“Among Us” is a multiplayer online social deduction game that was released in 2018 by InnerSloth studio. Recently, this game gained popularity as a way to interact with others during quarantine. The game takes place in a space-themed setting with 4 to 10 players, which are given one of two roles at the beginning of each round. The first role is the Crewmate. If a player is a Crewmate their primary objective is to complete a list of tasks to repair their spaceship, and when a task is completed a green progress bar fills. The Crewmates win if all the tasks are completed. The second role is the Impostor and, like the name suggests, these players may look like a Crewmate but they do not have the same objectives. For Impostors to win they must secretly sabotage the ship and eliminate the other players without being caught before the Crewmates finish all their tasks. The Crewmates can call a meeting to suss out who is the Impostor at any point with the emergency meeting button or if they discover an eliminated Crewmate. The game has a built-in text chatroom to conduct these meetings; however, in my classes I paired the communications application Discord with the game. I opted for this application over Zoom because there is a deafen feature which allows players who have been eliminated to talk to each other without active players hearing them.

Class Activity

This activity was introduced to first year students studying English at my university to increase their motivation since their university experience has been purely online. There was a noticeable decrease in motivation when the choice to stay online was announced. To combat this I felt it was my job as an instructor to try something to raise the spirits in the class. The activity was conducted over two lessons; the first was an asynchronous language focus lesson, while the second synchronous lesson consisted of the game play itself.

Lesson 1: Scaffolding

The first lesson was designed to familiarize the learners with the game and key language aspects they would need to be successful with this activity. This was an asynchronous lesson. Many of my students had never played this game before, and I did not want there to be an accessibility barrier based on the game play, so the first asynchronous task they had was to watch a YouTube video I made that described the game, how to complete the Crewmates’ task, and how to play as the Impostor. The Skeld map, which is one of three maps you can play, was also introduced to the learners with the key location vocabulary and other useful vocabulary such as sabotage, innocent, suspicious, vote, and eject.

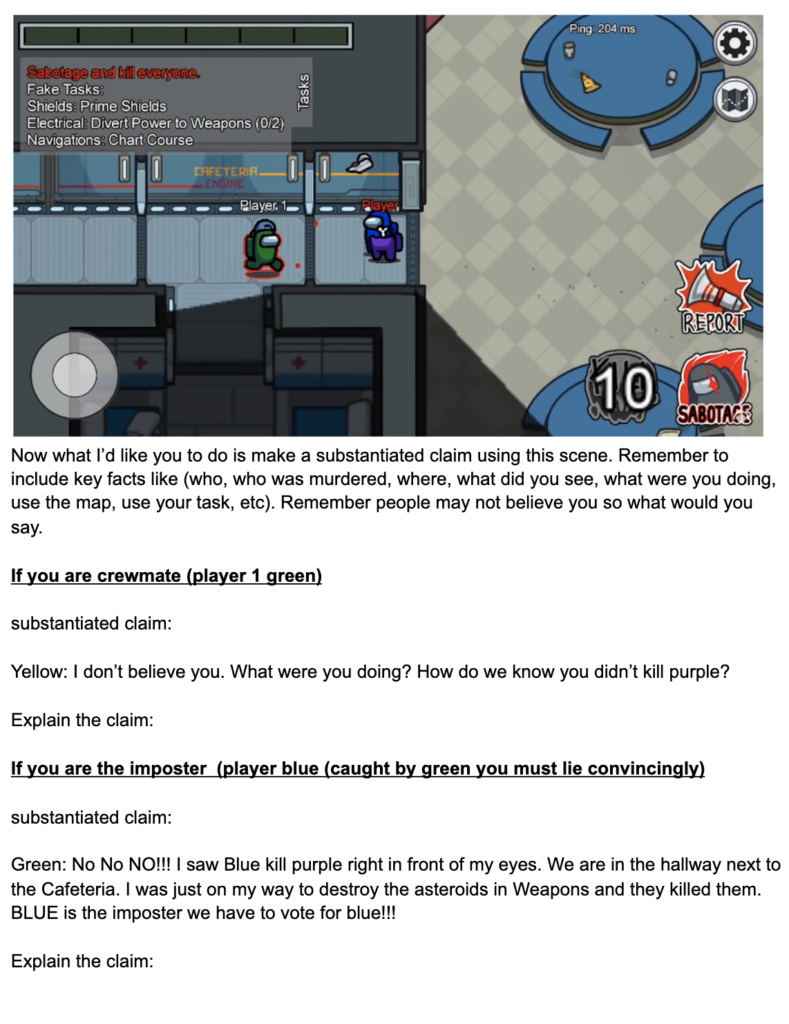

This game is based on discussion and persuasion. To prepare the language learners for this game and to have a linguistic focus I introduced how to form and use substantiated claims. This was an important structure for the learners to master since these claims included the conclusion and the premise or reason. Being able to use substantiated claims makes an argument more believable and provides extra information that may be vital to the vote. Once the learners were comfortable using this structure they were asked to create two dialogs using substantiated claims based on a scene from a round of “Among Us”. The first was from the perspective of the Crewmate witnessing the Impostor eliminate another player. The second dialog was from the Impostor’s perspective being caught in the act. They were reminded to add key facts in their claims like who did they see, who was eliminated, where did it happen, what did you see, what were you doing, where were they going (use the locations from the map), and what task were they doing.

Lesson 2: Game Play

The second lesson was a synchronous class in which we played “Among Us”. First, I made sure the learners were comfortable using Discord and understood the deafen function. We played with deafen on when the round started and if a player was eliminated during the round they could un-deafen and talk with each other, but if a meeting was called they had to mute again. As the biggest lobby on “Among Us” can only host 10 players, I had a student that had previously played host one room, while I hosted the second. I split the students into two rooms on Discord and we shared the private code to our lobbies. We played several rounds of the game and I popped between both rooms to check in on the students. Even if I wasn’t in the room the learners were communicating in English and were really into the game. To keep the game play fresh, we mixed the rooms a few times so everyone in the class had a chance to play together. After the game play the learners were asked to reflect on the activity.

Reactions

Overall the activity was received extremely well and it seemed to reignite the learners’ drive for language learning. Several learners reflected that the focus on substantiated claims has proven useful in our Model United Nations unit as they feel they can make clearer and more logical arguments. The main themes that learners valued while taking part in this activity was the sense of community it created and the aspect of ‘fun and excitement’ that had been lacking in the online courses. First, addressing the sense of community – like mentioned earlier, the freshmen this year have had a very different university experience than that of previous years. For our students joining clubs, taking part in on-campus events, and generally having a group to hang out with outside of class times defines their university life. This year many of their interactions with their peers have been restricted to class time with a rigid structure to cover the required teaching materials. Hence, students haven’t had a chance to build a deeper connection to their peers. This activity gave the learners a more casual environment to use English and build relationships.

On top of that it is important that learners enjoy the process of learning and this activity was able to provide that joy. Research has suggested that “playful experimentation” through imagination, creation, play, sharing, and reflection (creative learning spiral (Resnick, 2018, p.11) may lead to more creative expression and more authentic language production. This was true in this activity, as students needed to quickly deliver a message to have others act on a desired action. Reflecting on the task many expressed that the discussion was the most enjoyable aspect of the game play. They told me later that even after the class was over they still played a couple of rounds and would like to play again with the rest of their classmates.

Considerations

Before considering the addition of “Among Us” to your repertoire of online activities, there are a few things to consider. First, remember that this game is extremely fast-paced which may increase the cognitive load of the learners. If scaffolded correctly, one can reduce the intrinsic load related to the linguistic content (Chandler & Sweller, 1991). Furthermore, by providing examples and familiarizing the learners with the game play before the synchronous task, you can reduce extraneous and germane loads. Learners may also slip between their L1 and L2 out of excitement or lack of explanatory language, so it is important to provide plenty of examples. Something else to think about is the fact that the instructor cannot monitor both rooms at the same time, so if there is an issue learners will need a way to contact you. I would recommend this activity for intermediate learners (B1-B2 ) or above for students to get the most out of this lesson.

On the technical side, since currently “Among Us” is an extremely popular game, there is a chance that servers can be full. You can try a different region server to fix this issue, however, everyone in the class will need to be in the same region (North American, Europe, or Asia). Students may also lose connection, which will boot them from the game. If that happens there is no way for them to rejoin the game until the round ends. Like any new technology tool for education, there is a slight learning curve to using Discord. If you are using Discord some students may forget to un-deafen themselves during the discussion and the only way to contact them when this happens is on the text chat feature of Discord. Of course, this activity can be conducted over Zoom or on Google Meet if you feel more comfortable with these video chat applications.

This activity was designed for learners of English, however, as “Among Us” continues to develop, other interface languages are being added. InnerSloth studio is moving to include French, Italian, German, Spanish, Dutch, Russian, Portuguese, Japanese, Korean, and Filipino (Bisaya), with more languages to be added in the future. Hence, this game has the potential to be implemented in a variety of second language classrooms.

Conclusion

There are some factors an instructor should consider before implementing this activity in their classes. However, the joy and the camaraderie this activity can bring to an online class is worth the extra scaffolding that is needed for the success of this task. It is the sense of community that really makes this activity valuable. As Wright et. al. (2006) states, “Games also help the teacher to create contexts in which the language is useful and meaningful. The learners want to take part and in order to do so must understand what others are saying or have written, and they must speak or write in order to express their own point of view or give information” (p.2). This has become an extremely popular game to play and stream on social media and even politicians like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (AOC) have played with YouTubers and other streamers. When learners see these people playing on social media they can feel that this task is meaningful and the language they are using will help them communicate with others inside and outside of the classroom.

References

Chandler, P., & Sweller, J. (1991). Cognitive load theory and the format of instruction. Cognition and Instruction, 8(4), 293–332. doi:10.1207/s1532690xci0804_2

Dormer, R., Cacali, E., & Senna, M. (2017). Having a Blast with a Computer-Mediated Information Gap Task: Keep Talking & Nobody Explodes in the EFL Classroom. The Language Teacher, TLT wired, 4(41), 30–32. https://jalt-publications.org/node/27/articles/5944-having-blast-computer-mediated-information-gap-task-keep-talking-nobody-explod

Farber, M. (2016, January 18). History, Empathy, Systems Thinking, and Gaming. Edutopia. https://www.edutopia.org/blog/history-empathy-systems-thinking-gaming-matthew-farber

Resnick, M. (2018). Lifelong kindergarten: Cultivating creativity through projects, passion, peers, and play. MIT Press.

Thomas, M. & Reinders, H. (2010). Task-based language learning & teaching with technology. London, UK: Continuum.

Wright, A., Betteridge, D., & Buckby, M. (2006). Games for Language Learning (3rd ed., Cambridge Handbooks for Language Teachers). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511667145

Great idea! Would you be willing to share the introductory video you made?

Good to know great minds think alike Erin 😉