A Language Center Design Primer

By Felix Kronenberg, Associate Professor at Rhodes College and President – Elect of IALLT (International Association for Language Learning Technology).

By Felix Kronenberg, Associate Professor at Rhodes College and President – Elect of IALLT (International Association for Language Learning Technology).

“Creating spaces wherein diverse sorts of people can interact is a leitmotif of the modern world” (Gee, 2004, p. 79)

The history of the language lab/center is filled with paradigm shifts and disruptions. A few decades ago, the communicative approach made the audio-lingual labs appear like a faulty design. Later, digital file sharing made the constant tape duplication processes – and equipment – obsolete. Today, the device(s) in almost every student’s pockets and backpack increasingly make rooms full of desktop computers seem outdated. In a way, the language center is merely undergoing processes of massive disruptions like other areas of the world: books, music, films, cameras, calculators, flashlights – so much disruption in just a few years. Practices that have been taken for granted for years are all of a sudden either obsolete or forced to undergo a profound transformation. Language centers as well are not immune to the changes in an increasingly mobile and digital world. Because they are in most cases physical environments, they cannot adapt quickly enough. What seemed like a sensible and adaptable design and concept just a few years ago might already seem outdated and ill-suited today. How do you design a physical space so that it stays nimble, fresh, up-to-date, and useful?

The question of how to design a language center is not a good one to ask. Rather, we should start with the more fundamental questions: Why do we need a language center? Do we really need one? What is it supposed to “do”? Is the name, the concept, still relevant, or should we talk about language learning spaces instead? And how are those different from general (humanities) learning spaces? Those are difficult and painful questions, but if unanswered you won’t be able to design a good center. The questions are difficult to answer because at many institutions the mission that those centers need to fulfill is changing all the time. They must be answered at each institution individually. After all, language centers differ greatly: for example, a large center at a research university with several staff members is hardly the same as one at a liberal arts college which is run mostly by student workers.

The following dos and don’ts represent current good practices of language center design. I have culled them from different sources: IALLT’s recent Language Center Design book, recent survey data, journal articles, the ongoing book project tentatively entitled “From Language Lab to Language Center and Beyond: The Past, Present, and Future of the Language Center,” years of language center design workshops at the IALLT and FLEAT conferences, tips and suggestions from colleagues, and my own consulting work with various universities in the U.S. and abroad. The goal of this article is to offer direct advice. Please consult the bibliography for more resources and research on the topic.

FOCUS ON THE HUMAN BEINGS

For many years, language lab/center designers have focused on technology and built around it. In a way, that was necessary because such earlier spaces provided specialized hardware, which often was quite sizeable. The people in these spaces were rather an afterthought. Today, instructors and students have choices due to the mobility and ubiquity of our digital devices, which allows us to focus on people again in the design of physical language learning environments. About a decade ago, Wang posed the question: “Since more and more computer technology is available even in the far reaches of the student dorms, what draws students to still make use of the LLC?” (2006, p. 57) If a center is supposed to be successful, useful, even a desired space, it must offer more than access to technology. If we understand space as social, not merely physical – McGregor posits that “Space is literally made through our interactions” (2003, p. 354) – we should not ask what technology will be in the language center first (an architect colleague once told me that the fastest way to make a space look obsolete is to put a lot of technology into it). Today we are fortunate not to have to design around the technology, but rather think about the space first.

INVEST IN FURNITURE RATHER THAN TECHNOLOGY

When I get asked what the best use of one’s money is in the new or renovated language center, I usually recommend investing in furniture, not technology. Chairs and tables will outlive computers, and good, flexible, versatile furniture will allow for different forms of interaction and pedagogies.

|

|

|

A few comments that go beyond the basics: experiment with different types of furniture. It can be cost-neutral when you swap furniture with other units on campus for a period of time to test different options and configurations before buying. Try stools without directing backs, standing desks, and different types of chairs and tables. Avoid buying only one type of furniture; a mix of different seating and table options will offer patrons a feeling of perceived control. Flexibility is a must for sustainable and smart design. I decided to have even our front desk built to be mobile, and we changed its location several times over the past years as we observed people movement flows. One piece of advice: we cannot understand how people use a space until we have observed them in it. So it is highly advisable not only to build with flexibility and adaptability in mind, but also to be brave and leave enough gaps in the design – future uses will most certainly arise! It is okay and inevitable that we will not build a perfect space in the beginning. “The architect and educational designer Bruce A. Jilk in the USA has argued that there has been a tendency in the past to over-design schools, and that designers need to reconsider their preoccupation with suggesting all the functions for the teaching and learning environment. Jilk suggests a ‘montage of gaps’ to draw attention to the significance of the spaces and places in between the formal learning environments; these can be left incomplete in order to stimulate a continuous design response among the users of these spaces over time.” (Grosvenor & Burke, 2008, p. 166-67) Rapoport speaks of the “need for underdesign rather than overdesign, of loose fit as opposed to tight fit.” (1990, p. 22) The need to underdesign includes the need to build in a future budget for design changes. In general, building projects have a large budget during the initial phase, leaving relatively little for successive years. We do not know what will be happening in the next decades, so we must be open for ever faster occurring paradigm shifts and disruptive developments.

BE UNIQUE

Do not replicate features that are available elsewhere on campus. For example, if there is a recording booth already on campus, you should think a lot about whether you will need another one in the language center.

How is the language center distinct from other units on campus? Is it just another computer lab or classroom? What can be done in it that cannot be done elsewhere? These questions should not only be answered before the design process begins; they should be on the table on a regular basis after the space has been built.

If the physical space is not unique, then it might be under pressure to be opened up for less specialized use and might be absorbed into a larger unit on campus.

DON’T DO IT ALONE

Space design is a complex process, and it should never be done alone. Just getting the basic, such as doors, walls, lighting, sound, windows and window shades, etc. right, is a complicated endeavor. Experts, such as architects, campus planners, interior designer, and IT staff, are needed for many areas.

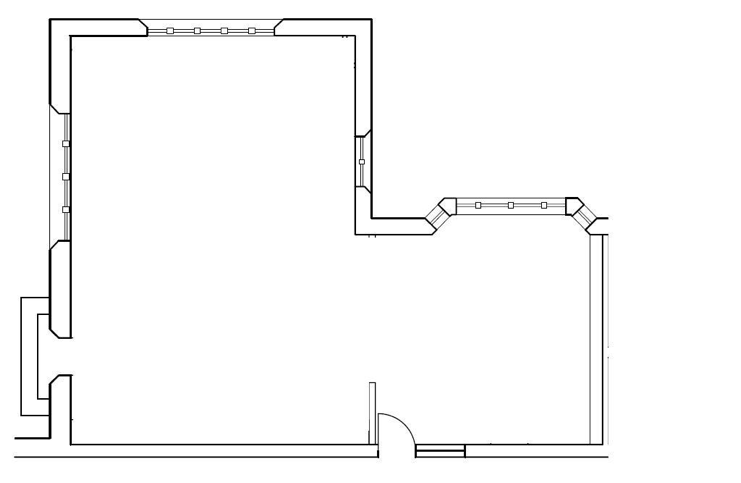

But they should not be the only ones because the space decisions go beyond the basic physical aspects of the learning environment. Kroll argues that “[a]rchitecture is an instrument that can encourage or block human behaviors – all the more powerful because its language is addressed to the unconscious. If it is designed entirely by specialists, if it is fixed and untouchable, it cannot possibly respond to the diversity and creativity of those who use it.” (1984, p. 167) Involving all constituents – faculty, staff, students, parents, alumni, etc. – is crucial during the planning phase. Establishing an advisory group that involves representatives from these groups is an important part. It would also be advisable to meet with all stakeholders individually and listen to their needs, concerns, and ideas. One exercise I often do with faculty who are involved with the creation of learning space is the “perfect classroom” doodling activity (see sample image from our 2010 center design): I ask each instructor to doodle on a modified blueprint, one that has everything removed but the unchangeable features, such as load-bearing walls. During that exercise I have them explain to me what features would make the planned space an ideal teaching/learning space for them.

CONCLUSION

The above tips are only a handful of dos and don’ts. For those who are involved in the process of a design or redesign of a language center, much more advice is needed than the space of this short article allows for. Crucial areas I haven’t even touched here include grant-writing, campus politics, marketing and outreach, transitory spaces and campus integration, semi-formal and informal learning spaces, and much more.

A useful resource for those new to the process is bringing a consultant to campus who has experience in the field of language center design. Attending an IALLT language center design workshop and reading dedicated literature on the topic is another (see below for some recommendations).

We have come a long way since the first language labs. In coming years, we need to answer the question of whether or not we even need to design new language centers. Specialized support for novel and innovative ways of teaching and learning as well as new technologies is certainly on the rise in coming years. How a physical environment that supports these needs should look like is difficult to predict, but following general good practice might help us be prepared for that future.

Did you recently renovate your learning space(s), tell us about your experience!

RECOMMENDED READING AND MORE INFORMATION

- http://www.felixkronenberg.com/

- Kronenberg, F. A. Language Center Design and Management in the Post-Language Laboratory Era. IALLT Journal, 44(1), 1-16, 2014.

- Kronenberg, F. A. Language center design. Moorhead, MN: International Association for Language Learning and Technology, 2011.

- http://www.languagetechnologybootcamp.org/

- http://spaces.languagetechnologybootcamp.org/

REFERENCES

Grosvenor, Ian, and Catherine Burke. School. London: Reaktion Books, 2008.

McGregor, Jane. Making Spaces: Teacher Workplace Topologies. 3rd ed. Vol. 11. Pedagogy, Culture and Society. 353–77, 2003.

Rapoport, Amos. The Meaning of the Built Environment: A Nonverbal Communication Approach. Tucson, Arizona: University of Arizona Press, 1990.

Wang, Jing. The Changing Role of a Language Learning Center at a Liberal Arts College in the Midst of Technological Development. IALLT Journal 38 (1): 56–65, 2006.

Picture 3 – Mobile front desk (back)

Picture 3 – Mobile front desk (back) Picture 4 – Mobile front desk (front)

Picture 4 – Mobile front desk (front)